From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 13 No 5 (Oct 2019)

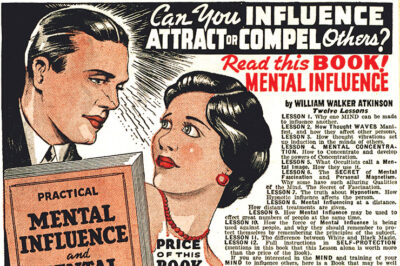

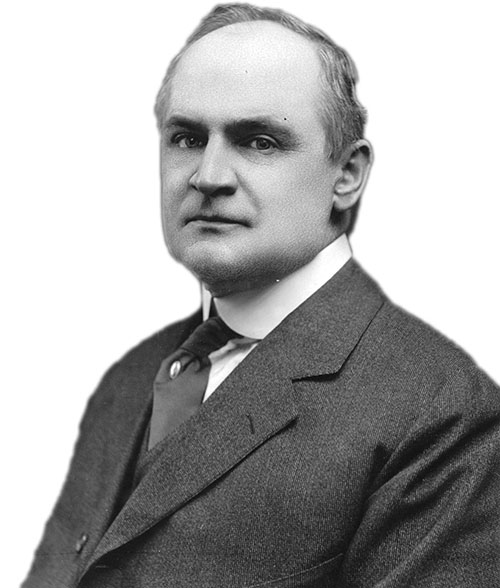

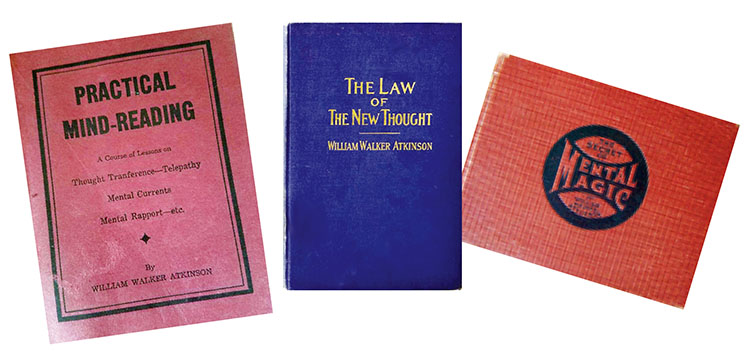

William Walker Atkinson was one of the most influential and mysterious metaphysical writers of the twentieth century. Under an array of different pseudonyms, Atkinson authored over a hundred books and close to a thousand magazine articles in a prolific career that began later in his life after a breakdown pushed him out of a successful legal career.

While known during his own lifetime, Atkinson’s works continued to have a remarkable and widespread influence after his death and up to the present. His pen helped to shape everything from yoga and Reiki to the Prosperity Gospel and the Law of Attraction.

Atkinson was born in Baltimore, Maryland, USA in 1862 to a solidly middle-class family who had connections to some of the city’s more prestigious and established families. His father and grandfather both owned grocery stores, and as he grew up and worked in his father’s business, William Walker Atkinson seemed fated to join them.

When he was just twenty-one, Atkinson suffered a breakdown. Seemingly despondent from a case of unrequited love, the younger Atkinson disappeared from Baltimore and sent a series of suicide notes from a hotel in Philadelphia a few days later. Not long after, he started reading books on Theosophy and began a study of esotericism that not only seemed to stabilise him and give him direction in the moment, but for the next half-century.

He then travelled throughout the eastern half of the United States for several years in search of a career that could be of his own making. Atkinson moved from one job to another and tried his hand in sales and office work without anything really taking hold, eventually finding his vocation as an attorney. In 1893, Atkinson began to study the law, serving first as an apprentice and then alongside a senior attorney in central Pennsylvania.

Atkinson thrived as a lawyer, and not long after he moved to another city to start a practice of his own, and he was invited back to become a partner with his former mentor. The future seemed bright for Atkinson and his young family, but when the perfunctory transfer of his legal credentials from one county to another was unexpectedly denied, that future was thrown into doubt. Left with few options, Atkinson moved his family in with his brother-in-law in Philadelphia and promptly had another breakdown that saw him disappear for six weeks.

His Great Work Begins

In later accounts of this time, Atkinson described being brought to the brink of collapse on all levels through overwork and anxiety. While he was coy about what exactly happened during the time of his absence, when he reappeared Atkinson quickly gathered up his family and moved to Chicago where he changed his occupation and became an enthusiastic author and proponent of New Thought – a web of beliefs and practices that hold that one’s thoughts affect health, well-being and circumstances – and he took to it with a convert’s zeal.

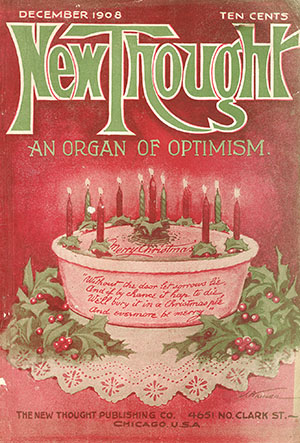

Atkinson started in his new career by writing and serving as the associate editor for a magazine titled Suggestion, and by the end of 1901 he was the editor of another Chicago-based periodical titled New Thought. As he continued to write and give lectures, compilations of Atkinson’s work began to be published in book form.

While Atkinson’s nascent life as a writer might seem to have been a dramatic shift, it brought together much of his past. His early interest in Theosophy appears throughout his works in direct references to Helena Blavatsky and use of the term “secret doctrine,” and in a worldview indebted to its perennial philosophy that saw a validity and interconnectedness in the different spiritual traditions of the world. Atkinson incorporated the works on self-help and physical culture he absorbed during his sojourns as a clerk and salesman, and from his time as an attorney he took a fondness for describing the universe as a set of laws, as well as the ability to eloquently argue a point.

With Atkinson as editor and chief contributor, the readership of New Thought swelled, and its total circulation doubled and then doubled again. This was no accident. Many scholars have suggested that New Thought’s popularity is best understood in the context of swift and massive changes that were happening in American society as the Gilded Age transitioned into the Progressive Era and large numbers of Americans moved into the cities to work jobs in sales or inside offices.

With theories that were simultaneously scientific and magical, New Thought gave explanations for why some people were successful and others were not, and it offered the possibility for advancement and improvement to those who had little more than their thoughts and desires.

For his part, Atkinson wrote to his audience with a voice that was simultaneously clear, authoritative, sympathetic, and profoundly democratic. Always a champion of the individual and those who worked hard, he saw the workings of New Thought as easily in the empires of newly minted industrial magnates as in the hustle of the young newspaper hawkers he admired on the streets of Chicago. Atkinson also regularly invited readers to visit him in his office and answered their letters in a regular column in New Thought with counsel that was as kind as it was direct.

Atkinson held a view of New Thought that was both generous in theory and practical in its application. He saw little that was “new” in New Thought but understood it as only the most recent manifestation of a long and varied line of systems that extended all the way back to ancient India. At the same time, Atkinson approached New Thought like a scientist and saw the everyday world as its proving ground that could test and refine its ideas, with its ultimate value in how it could help people in their daily lives.

Unlike many of his contemporaries and those later influenced by New Thought, Atkinson never saw its teachings as just a magical way to manifest desires, but rather as a method of strengthening and clarifying one’s aims that always needed to be paired with hard work. One of Atkinson’s sayings was “Hold the Thought and Hustle.” He also refused to see material wealth as the sole worthy aim, but instead glorified those who were creative, productive, and felt at home in the world as themselves.

‘Yogi Ramacharaka’

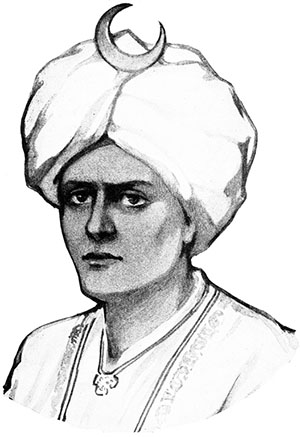

While he was at the helm of New Thought, Atkinson began to author monthly mail-order lessons on yoga under the name ‘Yogi Ramacharaka’ that soon developed into a series of books published by the Yogi Publication Society, housed in Chicago’s Masonic Temple skyscraper. Atkinson did not seem to be concerned with being a conduit for the pure ancient wisdom of India. For him, the yogi was an ideal type – energetic, efficient, and attuned with nature – and the yoga he offered the public as Yogi Ramacharaka was a mixture of physical culture, contemporary science, New Thought philosophy, and self-help techniques.

Yogi Ramacharaka was one of the earliest of over a dozen different pseudonyms Atkinson used during his writing career that would become a source of confusion and speculation after his death. Upon close inspection, his various pen names align with different publishers and distinct periods of time. The most likely explanation for them is that they allowed someone so prolific to publish with several companies simultaneously and to do so without flooding the market.

Importantly, Atkinson never distanced himself from any of his writing. In the biographical entries he submitted to reference books such as Who’s Who in America, he openly claimed authorship of all his pseudonymous works, and in the personal copies of his pseudonymous books that were left to his family, he personally inscribed “I Wrote This” next to his initials on their inside covers.

As New Thought magazine became increasingly successful, its manager Sydney Flower used its pages to promote dubious products (including a health cigar) and investment schemes. Flower quickly became the target of mockery in several newspapers and ran afoul of federal postal authorities who halted New Thought magazine’s use of the mail as part of a fraud order just before Christmas in 1904.

Atkinson moved with his family to Southern California a few months later. It was a decision he claimed was for the climate and change of scenery, but as he had carefully distanced himself from Flower during this time – reminding readers in print that he was simply a writer and editor who had nothing to do with the “business side” of the magazine – the move undoubtedly had the added benefit of putting distance between himself and Flower’s legal troubles.

Relocating to Los Angeles established a pattern that would see Atkinson and his family move between Chicago and California a total of three times, staying in each city for several years at a stretch. Both cities were active hubs of metaphysical and esoteric activity, and were separately described by newspapers as claimants to the title of America’s “cult capital.” Atkinson’s presence in these locations – combined with his affable disposition and position as an author and lecturer – brought him into contact with an impressive list of important and influential figures in the metaphysical world. The heart of the Los Angeles scene was Blanchard Hall and for the next few years Atkinson regularly lectured to packed crowds in its large 800-seat auditorium and teach classes in its smaller meeting rooms.

One of the most important connections Atkinson made in Los Angeles was with Baba Bharati, a Bengali-born Krishna devotee who had recently arrived in the United States. Atkinson wrote a pair of articles for Bharati’s magazine, The Light of India, and warmly described their friendship. Bharati was also influenced by Atkinson, and after their meetings he began to describe yoga with the New Thought-inspired phrase “Thought Force.” It was likely through Bharati’s influence, if not direction, that soon after Atkinson left California and edited two volumes of Hindu sacred texts for a popular American audience – The Bhagavad Gita and The Spirit of the Upanishads – under his pseudonym Yogi Ramacharaka.

When Atkinson returned to Chicago in late-1907 he entered into an astonishing five-year period in which he was at his most prolific and eloquent, publishing over forty books and one hundred magazine articles. One account of Atkinson’s writing process during this time claimed that he would immerse himself in the study of a topic and then, once “loaded up,” write in a rapid outpouring with the office assistant setting up the type for each page as soon as Atkinson was done writing it.1 This process not only explains Atkinson’s productivity but also the repetition of ideas and minor typos in his works during these years.

The Kybalion

Early in this period, Atkinson wrote a self-described “little volume” called The Kybalion under the cryptic pseudonym “Three Initiates.” At the core of The Kybalion were seven axiomatic laws – such as the Principle of Correspondence and the Principle of Vibration – that were described as originating with the mythic Hermes Trismegistus and carefully passed down through the ages from teachers to select students. While The Kybalion claimed to be ancient, Egyptian, and Hermetic, it was much more a product of modern American New Thought, one reason it resonated so strongly with its audience.

Although he distanced himself from the business affairs of New Thought magazine, William Walker Atkinson never stopped contributing to it, and he faithfully discharged articles and regular columns to its readers as he moved around the country, and the magazine changed hands. For a short while in 1910, Atkinson even resumed his duties as editor for New Thought before the periodical dissolved.

Atkinson moved back to California in 1913 and settled just outside Los Angeles in the city of Pasadena for a few years. He took over noon weekday meetings in Blanchard Hall for Annie Rix Militz, the founder of the New Thought group known as the Home of Truth, at times with hundreds of people in attendance.

Even though Atkinson was not serving as the editor of a magazine during this time, he was a regular contributor to Elizabeth Towne’s Nautilus. Many of these pieces were reprinted in newspapers throughout the United States – from the San Francisco Chronicle and the Chicago Tribune to a host of smaller papers in the Midwest – and they were perhaps the greatest measure of visibility Atkinson received during his lifetime.

When Atkinson returned to Chicago in 1916 he entered familiar work with old partners and took on the editorship of a new magazine titled Advanced Thought, owned by the same couple who ran the Yogi Publication Society. For four years, Atkinson was at the helm of Advanced Thought, and in many ways the magazine was a one-man operation. Atkinson served as not only its editor but through columns and articles under his own name and supplemental pieces under his various pseudonyms, he supplied nearly all of the non-advertisement copy for some issues.

A few years before Atkinson’s return to the Midwest, the poet Carl Sandburg personified Chicago as a hard-working young man and gave it the moniker “City of Broad Shoulders.” Atkinson held Chicago in the same regard and was always at his most productive when he lived there. He fell in love with the activity and industry. He first lived there in 1900, and once told readers of New Thought that he “long(ed) to walk down State Street, seeing the native Chicagoan in all his glory,” while he was temporarily relocated in New York.

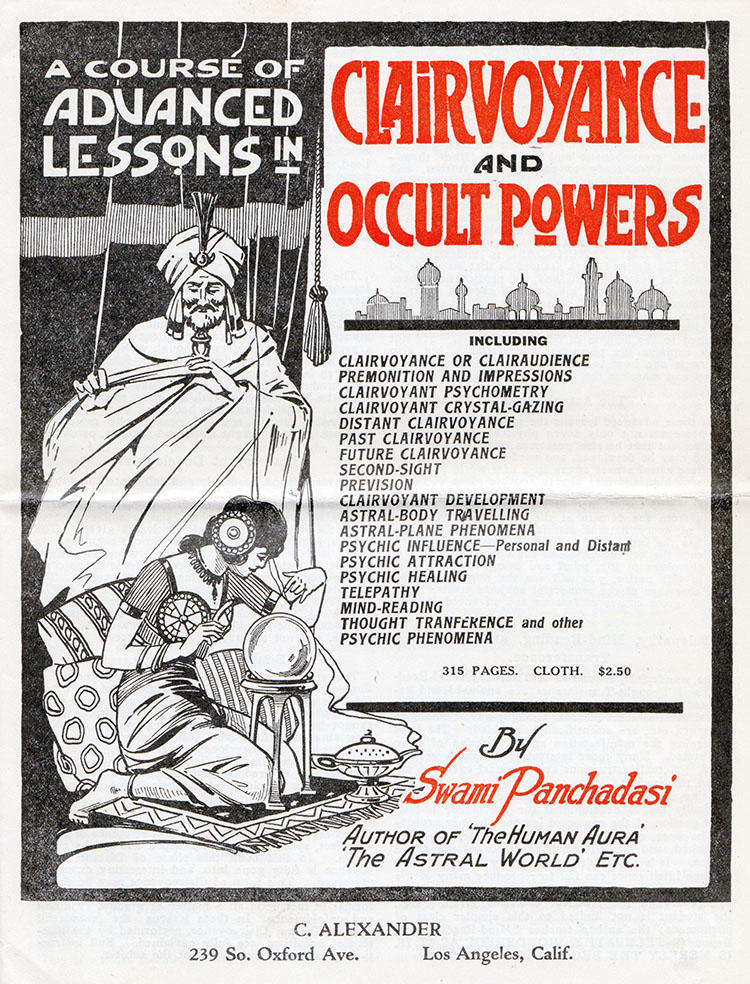

It was also during this period in Chicago that Atkinson authored the bulk of about fifteen different books under a trio of new pseudonyms. As Swami Panchadasi and Swami Bhakta Vishita, Atkinson wrote on subjects such as the human aura, the astral world, and the development of seership and psychic powers. While Atkinson frequently wrote about the dangers of the occult leading its students astray, he just as often made sense of occult phenomena through his understanding of the mind and its powers, and there is evidence that he worked with a crystal ball. The French-sounding pen name Theron Q. Dumont was used for more everyday application of mental powers: salesmanship, reading character, the development of memory, and increasing personal magnetism.

Atkinson, ever the optimist, could find the good in other New Thought figures and often supported them by giving guest lectures for their organisations. He did the same at regional and national gatherings of the International New Thought Alliance until he chafed at the increasing “churchianity” of the organisation.

At their 1916 annual meeting in Chicago, the International New Thought Alliance appointed a committee of “leading New Thought workers” to consider drafting a formal declaration of principles to be shared the following year in Saint Louis. While everyone else dutifully wrote affirmative creeds and eloquent statements of belief, William Walker Atkinson gave four terse and sharp paragraphs. According to him, New Thought could not be organised or set to fixed principles, rather New Thought “takes its own wherever it finds it” and “all attempts to… institutionalise it result merely in dwarfing and stultifying it.” Unsurprisingly, the statement went over poorly and caused others to either critique Atkinson or apologise on his behalf.

In 1922, Atkinson temporarily located to Detroit and published the twelve-volume Personal Power series of books with Edward Beals, largely a recapitulation of the main themes from Atkinson’s writing during the preceding two decades. From Detroit, Atkinson and his wife moved to Los Angeles where they remained until his death a decade later. Although age began to catch up with William Walker Atkinson during this time and his pace declined, he still gave regular lectures to New Thought congregations and lessons to small classes.

Atkinson only made sporadic efforts to publish his own work during the early part of his writing career and seemed to prefer leaving the business side of publishing for others to handle. While this decision left him and his heirs open to exploitation, and certainly cost him vast sums of money, it could also be seen as a reflection of his New Thought philosophy. Perhaps like his friend and mentor Helen Wilmans, Atkinson not only believed in the existence of a limitless potential supply of money and opportunity but regarded concern about money, even at the simple level of planning ahead for it in the future, to be erroneous and detrimental. For someone as prolific as Atkinson during the first decades of his career, this would have been a tenable strategy. But as his age increased and his health declined in the 1920s, it was no longer possible for him to write as he once did, and he only managed to produce a pair of unpublished manuscripts during the latter years of his life, The Seven Cosmic Laws and a primer on Theosophy.

In a tragic irony for the author whose words inspired so many to believe they could attain success and prosperity when William Walker Atkinson died in November of 1932 his family needed to borrow money for the funeral and burial.

“The Other Side of Life”

In one of his books written under the name Yogi Ramacharaka, Atkinson told his readers “that which we call death is but the other side of life.” There was no better example of this statement than his own life and legacy. After Atkinson’s physical death, his works took on remarkable lives of their own.

William Walker Atkinson was deeply suspicious of any institution or system that would limit the freedom of the individual seeker. He was similarly distrustful of teachers who positioned themselves before the public as unquestionable authorities or objects of devotion. In his writings, Atkinson constantly counselled readers to test his teachings in their own lives, take what was useful for them, and discard what was not. In his career, Atkinson never made any serious efforts to establish his own church or institution like so many of his peers, preferring to simply write, lecture, and hold classes with small groups of students.

These decisions, along with his liberal use of pseudonyms, profoundly affected Atkinson’s legacy. Paradoxically, they allowed for his ideas to spread widely around the world and become enormously influential in various realms, while at the same time obscuring William Walker Atkinson as their creator.

Even before Atkinson wrote the last of the Yogi Ramacharaka books in 1912, they began to be translated into numerous languages and disseminate around the world. Japan was particularly receptive to the works of Yogi Ramacharaka as it was in the midst of massive interest in mental healing and had recently endured a large epidemic of tuberculosis. Books like the Science of Breath and concepts like prana were translated into Japanese, finding their way into the healing system of Reiki and the work of the influential positive thinking guru Nakamura Tempu who claimed to have studied with Yogi Ramacharaka in India.

Translations of the Yogi Ramacharaka books into Russian quickly became influential among artists and the intelligentsia, and were an important part of Konstantin Stanislavsky’s acting system which in turn influenced Lee Strasberg who trained generations of the most accomplished and celebrated actors in the United States with his ‘Method’ techniques. One young woman in Latvia, influenced by one of the Yogi Ramacharaka books translated into Russian, was Eugenie V. Peterson who would later travel to India and study with T. Krishnamacharaya. As Indra Devi, she became one of the most influential and well-travelled promulgators of yoga in the twentieth century.

During the interwar decades of the 1920s and 1930s, dozens of South Asian immigrants in the United States took up the profession of travelling yoga teacher and lectured to tens of thousands of people across the country after the American government declared them ineligible for citizenship. These newly-minted swamis and gurus found sets of yogic exercises and lessons lying in wait within the Yogi Ramacharaka books. In a confusing reversal, they presented the work of the American lawyer as ancient Indian wisdom to their audiences, some going so far as to sell, and even autograph, copies of the Ramacharaka books to their students.

In the decades following his death, Atkinson’s books under his own name and several of his pseudonyms were widely distributed and republished by numerous mail-order companies. Bruce King – the man widely credited with popularising astrology under the moniker ‘Zolar’ – filled the pages of his official magazines Astrology and Horoscope during the late-Fifties to mid-Sixties with uncredited excerpts from Atkinson’s books while advertising several titles by Atkinson and Swami Panchadasi for sale directly from Zolar’s New York headquarters.

By far, Atkinson’s most influential work was The Kybalion. The clear writing and organisation of The Kybalion made it accessible to a wide readership. The vague penname authorship by the “Three Initiates,” the name and location of the publisher (The Yogi Publication Society in the Masonic Temple Building of Chicago), and its claims to ancient Hermetic wisdom, gave the book an air of mystery and intrigue that allowed for endless speculation and for a diverse range of groups to see it as their own.

The hand of The Kybalion can be seen in the writings of Norman Vincent Peale, the author of The Power of Positive Thinking, and one of the key popularisers of positive thinking and the Prosperity Gospel, which holds for many Christians that God’s will is that they be physically healthy and financially well off. A 1995 article found that Peale likely took many central ideas for his best-selling work from The Kybalion, and did so by way of the metaphysical author Florence Scovel Shinn, citing among other things parallel uses of terms like “law” and “vibration” in Peale’s work and The Kybalion.2

William Walker Atkinson took on a new life in the late-Sixties as his books were widely rediscovered and his ideas became part of the spiritual backdrop of the era. For many Hippies who discovered yoga, the thirteen titles by Yogi Ramacharaka were a reference library in waiting. So many people wrote to the Yogi Publication Society during this time desperate for more information on Yogi Ramacharaka that the publisher produced a fallacious stock response to answer them. According to one critic, the Yogi Ramacharaka books were one of the many sources mined by Carlos Castaneda, the anthropologist whose alleged encounters with the Yaqui teacher Don Juan turned on innumerable Hippies to shamanism and ideas of magical apprenticeship.3

The Kybalion also resonated deeply with Augustus Owsley Stanley, who mass-produced millions of doses of LSD, helped engineer the sound of the Grateful Dead, and was perhaps more responsible for the Hippie Counterculture of the 1960s than anyone else. Stanley described Atkinson’s book of Hermetic wisdom as “perfect… because it put into context all the things I had experienced on acid… Everything is connected, because it’s all being created by this one consciousness.”4

As times changed, Atkinson’s Kybalion continued to have remarkable staying power with a wide array of seekers and aspirants. Many African American thinkers took the Egyptian origins of Hermes Trismegistus described in The Kybalion and cast it as distinctly African wisdom, using the seven Hermetic principles in works of fine art, literature, self-help, psychology, family therapy, and even bounty hunting.

Pagans, Wiccans, and other products of the modern revival of witchcraft also drew from The Kybalion. Figures like Laurie Cabot claimed that “the seven Hermetic Laws (were) the basis of Witchcraft.”5 One newspaper in 1989 began a multi-part series titled “Understanding the New Age” by elucidating The Kybalion’s teaching as “the basis of all esoteric principles,” and that Atkinson’s “little volume” served as an introductory and foundational text for a variety of occult groups and Freemasons.

Some of the most striking examples of just how prolific and influential Atkinson was, and also how overlooked and under appreciated he is, come from cases in which people were influenced by several of Atkinson’s pseudonymous works without realising they came from the same hand.

The same overlap occurred in 2006 with the sudden and massive success of Rhonda Byrne’s self-help film turned book The Secret, which went on to sell over thirty million copies in over fifty languages and became a major cultural moment as it was feted and endorsed by Oprah Winfrey and other celebrities. While some critics and observers noted that The Secret was not much more than a repackaging of New Thought ideas, those familiar with the work of William Walker Atkinson would have seen his unspoken influence, both directly and indirectly, in Byrne’s creation through allusions to Hermetic wisdom and the constant use of “The Law of Attraction,” which Atkinson articulated over a century earlier.

It was a testament to not only his influence but how fresh and vital William Walker Atkinson’s work has remained over time. For another author to be used and forgotten after such a prolific career would seem an insult. But for Atkinson – someone who valued placing constructive ideas into the world over constructing his own prestige and always encouraging others to use what worked for them as they found it – it was entirely fitting.

Footnotes

1. From The Art and Practice of the Occult by Ophiel, Peach Publication Company, 1969

2. “Peale’s Secret Source” by George D. Exoo and John Gregory Tweed, Lutheran Quarterly, 1995

3. See Castaneda’s Journal: The Power and the Allegory by Richard de Mille, Capra Press, 1976

4. “Owsley Stanley: The King of LSD” by Robert Greenfield, Rolling Stone, 2007

5. The Power of the Witch by Laurie Cabot with Tom Cowan, Delacorte Press, 1989

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.