New Dawn 162

It is a pity that no researcher, while there was still time, ever spoke to the friends and relations who had known Julius Evola (1898–1974) in his youth. Like some other occult philosophers (Blavatsky and Gurdjieff come to mind), Evola covered his tracks, putting his apprentice years out of reach of the curious, then constructing an idealized biography.1 After his crippling injury in World War II he became an obscure and private figure, of little interest to the world in general, so that no one was prompted to go to Sicily, for instance, to try to find some cousins or to establish the status of the title “Baron” to which he sometimes answered. His few disciples, for their part, would never have had the bad manners to poke into the Master’s past, or to search out his aging school-fellows for insights into a level of his personality which he affected to despise.

Like his early hero Nietzsche, Giulio seems never to have been a child, but to have come into the world fully-formed and ready for his life’s mission. We know that he completed university studies in engineering, but disdained to receive a diploma, as being too bourgeois an ambition.2 He served in World War I as an artillery officer, without seeing any serious action. His first public appearance was at the age of twenty-one, exhibiting 54 abstract paintings (now avidly collected, and some of them in public collections) and participating in the Dadaist movement. After abruptly quitting that phase, he reappeared as commentator and translator of the Tao Te Ching. By his mid-twenties, at a time when most young men are still finding themselves, he had completed a series of essays on Magical Idealism, a scholarly study of Tantra, and an 800-page treatise which he sent to the most eminent Italian philosopher of the time, Benedetto Croce. With typical hauteur, Evola explained that:

For some years I have tried to organize my philosophical views into a system, mainly contained in an unpublished work entitled Theory of the Absolute Individual… I will release this volume, which has cost me several years of work, without any remuneration… For a number of reasons that I cannot go into here, the publication of the principal work represents something quite important to me, since, in the discipline I have followed, it is the opportunity to address freely and without reserve those for whom the general effect of my doctrine, expounded theoretically, is not merely an abstract scheme.3

Croce recommended publication. The publisher divided it into two volumes, Teoria dell’Individuo Assoluto (“Theory of the Absolute Individual”) and Fenomenologia dell’Individuo Assoluto (“Phenomenology of the Absolute Individual”). Evola’s premises had been anticipated by some German Romantics, but are generally quite foreign to Western philosophy. They are more familiar to readers of the Taoist, Tantric, alchemical, and magical texts that Evola was simultaneously studying. The Absolute Individual is the Self, seen as identical to the source of all being. Like the philosophy of Plotinus and other Neoplatonists, and even more like the philosophic writings of India and China, Evola’s doctrine includes, but also transcends, the dimensions of religious experience and mysticism. His twin volumes contain a history of subjective idealism, and a practical philosophy of life, based on the assumption that the Absolute Individual is the ultimate object of human aspiration and attainment. Evola, at least, must have been familiar with the experiences about which he was writing; apart from the authoritative tone of his “phenomenology,” there is the evidence of an entire life lived most rigorously in the spirit of this philosophy. It is a question for specialists whether his youthful experiences of the Absolute, some of which he admits were drug-induced, were temporary samadhis (to use the language of Yoga) that confirmed him in the truth of his intellectual convictions, or whether they effected a permanent change in his being, leaving him, no matter what his outer activities and circumstances, in the simultaneous awareness of absolute consciousness.

Evola’s concept of the Absolute Individual is inseparable from the other theme which he treated in this early period: that of Magical Idealism. “Magic” would remain his blanket-term for the methods taught in East and West that aim at the realization of the Absolute Individual. Questions such as whether magic is an irrational belief-system, or a reaction against modern science, would have been totally irrelevant to him. In his world, magic and the order of things classified as occult were the object of direct, intuitional knowledge. By stripping them of their superstitious associations and their Christian-Kabbalistic accretions, he reduced them to a form in which they could be sensibly and even scientifically discussed.

There are two reasons why Evola’s Magical Idealism is a landmark in the history of modern occultism (another inevitable blanket-term). First, he raises questions that have scarcely ever been addressed to practitioners or answered by theoreticians of the occult sciences, concerning the ultimate motivation and validity of the latter. The answers that one could expect from most occultists are either of a very lowly order, aiming at personal power, knowledge, wealth, etc., or else, in more serious figures such as Eliphas Lévi and A. E. Waite, they give way to dogma, making magic a handmaid to Judeo-Christian mysticism. The second reason is that Evola was not content to stay within the Western streams of magic, philosophy, or mysticism, but needed for the completion of his experiential system the input of the East. In both respects, his philosophical journey resembles that of Aleister Crowley, who, for all the differences in their “personal equations,”4 would probably not have disagreed with many of Evola’s principles. These did for magic what the Theosophists had done for the theoretical study of esotericism: opened it to the whole world.

By this time, Evola had been introduced by the Futurist painter Giacomo Balla to Arturo Reghini (1878–1946), a mathematics teacher active in many esoteric and fringe-masonic groups. Reghini performed two important services for the younger man. By his own example as a kind of Pythagorean nationalist, he convinced Evola – hitherto a student more of German Idealism and of the East – of the value of his native Italian heritage; and he introduced him to the writings of René Guénon (1886–1951), proponent of the “integral tradition.”

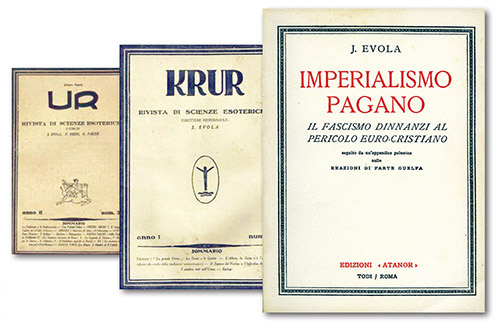

At the beginning of 1927 Evola and Reghini founded an esoteric group called the “Gruppo di Ur.” Its members included a number of Reghini’s previous collaborators, and had connections in Roman high society. The group produced a monthly journal which treated the whole spectrum of theoretical and practical magic, including classic texts from East and West, translations, and commentaries on their applicability to modern times. Some of the members worked alone; others formed “chains” for group work. Some of them wrote candidly of their own experiences, good or bad. Their magic was not of a superstitious kind but more in the practical mode of Rudolf Steiner’s “spiritual science,” for the group included some of Italy’s leading Anthroposophists. While the group itself was small, the fact that Ur was published in an edition of about 2,000 copies testifies to an astonishing level of interest in the Italy of those days.

One consequence of the friendship with Reghini was the theme of Evola’s next book, Imperialismo pagano (“Pagan Imperialism”), which was so violently anti-Catholic that it later became an embarrassment to him, and was never reissued during his lifetime. It is subtitled “Fascism facing the Euro-Christian peril,” and argues, as Reghini had been doing since the end of World War I, for the restoration of the Roman pagan tradition as the proper spiritual foundation for the new Italy. Mussolini, more alive to political necessities than swayed by “traditional” spirituality, dealt the death-blow to these pagan dreams in 1929 with his Concordat with the Roman Church. The Duce remained a reader of Evola and his protector, up to a point, despite the philosopher’s fearless criticisms of Fascism.

The insistence, henceforth in Evola’s work, on “Tradition” is the legacy of Guénon, whose early writings had propounded the idea of a single primordial tradition from which the various religions were offshoots, and which contained in symbolic form the basic metaphysical truths about the universe and man’s self-realization. The Absolute Individual that Evola had found in Taoism and Tantra, Guénon had expounded as the Supreme Identity of the Vedanta. It seemed clear to both of them that the same ultimate truths and teachings were to be found at the deepest layer of every authentic tradition.

Unlike Guénon, Evola was unsympathetic to exoteric religion and dubious about the Judeo-Christian tradition, which was so displeasing to him on a political and aesthetic level. He preferred other strands that had kept the authentic tradition alive in the West, foremost among which was alchemy. His contributions to Ur and Krur included many essays on this subject that he later gathered and expanded into a book on the Hermetic Tradition. In the history of alchemy in the twentieth century, Evola’s work represents a third stream, distinct from the practical, laboratory alchemy of Fulcanelli, Eugène Canseliet, Frater Albertus, Jean Dubuis, and their disciples, and equally distinct from the psychologized alchemy of Herbert Silberer or Carl Jung. Evola’s Hermetic Tradition is instead a cosmology, combined with a method for self-realization, in which sulphur and mercury, conjunction, transmutation, etc., are the names of otherwise undefinable states of mind and soul. Although it is not made explicit in the text, Evola’s alchemical method, like much else in occult practice, centres on the deliberate separation of consciousness from the body and on operations performed in the “astral world” or the world of the Imagination (taking this term in the sense used by William Blake or Henry Corbin), which require more than the usual degree of concentration and courage.

The more one mentions things of this kind, the greater is the tendency to associate Evola with other modern occultists, in the broad sense of the term. But his next book drew the line firmly between himself and them, being a denunciation of the “Mask and True Face of Contemporary Spiritualism.” It was based on articles he had already published critical of Spiritualism, Psychoanalysis, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, the French occultists, etc., and it served the same purpose as Guénon’s earlier works against Theosophy and Spiritualism: it defined the field, the sources, and the individuals that were unacceptable to “traditionalists.” With Pagan Imperialism, this book established a dualist, even Manichean trend, always latent in Evola’s character, but which in his earlier works had not yet become the source of his creative energy. Now it was not enough to speak of the various royal paths by which the “superior man” (to use the I Ching’s expression) becomes the Absolute Individual: the machinations of inferior men (and women) had to be laid bare, and war had to be declared against them.

Just as Evola’s early explorations in art, philosophy, psychedelics and magic had found their expression in the Theory of the Absolute Individual, so now he gathered his paganism, his sense of tradition, his political consciousness, and his contempt for most of the human race into definitive form and his most important and representative work: Rivolta contro il mondo moderno (“Revolt Against the Modern World”). This revolt was urged in the name of a primordial tradition whose metaphysical and cosmological principles occupy the first half of the book, while the other half is concerned with the process that led to the modern aberration. The fundamental assumption, without which Revolt makes no sense whatever, is the cyclical principle of history that is most fully developed in the Hindu system of four Yugas or world-ages (Satya, Treta, Dvapara and Kali Yuga), and also known to the Greeks as the Ages of Gold, Silver, Bronze and Iron. Evola accepts this, just as Guénon did, with the corollary that modernity is a phenomenon of the last part of the Kali Yuga or Age of Iron – after whose cataclysmic ending a new Golden Age will dawn, as certainly as the sun rises every morning.5

Guénon and Evola both believed in a previous Golden Age with a perfectly ordered primordial tradition, situated in the Arctic if not positively at the North Pole. For Evola, at least, there seemed to be tangible proof in Herman Wirth’s collection of prehistoric symbols from the circumpolar regions. But the greatest value of Revolt may be as an epic work of the imagination, which like all epics offers an escape into a world more comprehensible than our own, if no less tragic. Evola’s exposition of the orderly cosmos of Tradition and its fall, if not historically verifiable, is a creative enterprise on a Wagnerian scale that, like a great opera, does not have to be “true” in order to be an inspiration and an enrichment to its audience.

If the Traditionalist concept of cyclical history is correct, the modern world is the inevitable consequence of the tail-end of the cycle. What else could one expect from the Dark Age, the Age of Iron, or the Kali Yuga? It is as inevitable as night, winter, or natural death. Yet Evola and the other Traditionalists rage against its secularism, its social organizations, its confusion of gender-roles, its materialism and vulgarity, its racial and spiritual degradation. Above all, there is Evola’s pervasive theme, apparently derived from his early reading of the Swiss anthropologist Bachofen, of the spiritual superiority of the masculine over the feminine, contrasting the virile, primordial, Arctic, “Uranian” and “Olympian” way with the Southern, orgiastic, sentimental, Dionysian way of the Mother-goddess. The former, one gathers, is the path to the Absolute Individual, while the latter leads only to extinction on the wheel of the Eternal Return.

Only in modern times could someone have thought and written as Evola did, rejecting his native environment (whether one thinks of this as Italian Catholicism or as the rootless materialism of the Western world) and deliberately choosing an invented, or at least a foreign (because fundamentally Eastern) mode of thought. The critic of modernity is an essentially modern phenomenon, and his cultural pessimism, as it is generally known today, a natural reaction to events in Europe which none could ignore, least of all one of Evola’s warrior disposition. For all the lapidary certainties of his writing, Evola was looking for something to hold on to during the 1930s. He had been disappointed as Fascism cosied up to the Church and compromised itself with the bourgeois and proletarian world, even though he never found it so degraded as the rival systems of American capitalism or Soviet communism. During this decade his glance wandered continually to Germany, hoping to find there a political realization closer to his ideals. Fluent in German, he made several semi-official visits to Germany and Austria between 1934 and 1941 to give lectures and to meet dignitaries of the Schützstaffel (the “SS”). But these encounters also left a residue of mutual disillusionment: his hosts found him too unworldly and idealistic; he found National Socialism too narrowly Pangermanist; and the Italian regime became so uneasy about his activities that in 1942 it temporarily withdrew his passport.

Two themes dominated Evola’s thought after the completion of Revolt Against the Modern World. One of them had been present incidentally in that book: the theme of race, and in particular the connection of the primordial tradition with a pure Hyperborean race that had interbred, after the destruction of its Arctic homeland, with the inferior races of the South. After Hitler’s rise to power, Mussolini’s German allies began to exert pressure on a Fascist system that had been quite innocent of anti-Semitism and racism, at least until the Abyssinian Campaign. Evola now became a self-appointed authority on this topic. With obsessive diligence he addressed both theory and practice in numerous articles and two full-length books, Il mito del sangue (“The Myth of Blood”), and Sintesi della dottrina della razza (“Synthesis of Racial Doctrine”). Both books were illustrated with photographs, some taken from anthropological sources, others being of contemporary figures including Rudolf Steiner. Evola also addressed “Three Aspects of the Jewish problem: in the Spiritual World, in the Cultural World, in the Socio-Economic World.” With this project, he attempted to give Fascism its own racial philosophy, distinct from that of the National Socialists, and in 1943 it was accepted, in principle, by Mussolini. The core of Evola’s theory was that race is of three kinds. One of these is the sense in which the term is generally used, to indicate physical and genetic types: this he calls the “race of the body.” The second is the “race of the soul,” which is expressed in art and culture; the third, the “race of the spirit,” expressed in religion, philosophy and initiation. Evola’s fundamental disagreement with the National Socialists was that, like cattle-breeders, they considered only people’s biological or bodily race: in his view, the least significant of the three. It is no wonder that the SS found him unworldly.

The American-Italian scholar Dana Lloyd Thomas has found that this theory, as found in Evola’s books, is quite far removed from the polemical and often crude racism of his journalism. Thomas concludes that Evola’s studies, though presented as objective and historical, served two purposes: they made racism a respectable area of study, and all the examples he gave came to the same conclusion, affirming the superiority (spiritual as well as physical) of the “Nordic race” that was effectively equated with the Germans.6 Thomas’s project, stemming from honest moral conviction, needs to be balanced by the recent account of Evola’s war years, traced almost day-by-day through unprecedented archival research (see note 2). The author, Gianfranco De Turris, who has been writing about Evola for over forty years, is equally motivated by a desire for justice towards a philosopher who has been vilified like none other, and gifted with insight into circumstances that were very different from those of today.

The other theme that occupied Evola in the pre-war years also reflected his Germanophilia: he developed an admiration for the high Middle Ages that resulted in a book on the “Mystery of the Grail.” For whatever reason,7 his historical allegiances had now changed, and it was no longer ancient Rome, from Romulus to Augustus, that seemed to him to incarnate the last worthy manifestation of the tradition, but the “Holy Roman Empire of the German People” inaugurated by Charlemagne’s consecration in the year 800. In his book, Evola connects the Grail myths on the one hand with the prehistoric Hyperborean tradition, and on the other with the resurgence of the imperial and knightly spirit in the Middle Ages: no matter that Charlemagne was the pitiless suppressor of Nordic paganism, or that the Holy Roman Empire derived its authority from the church that Evola had so reviled in Pagan Imperialism. This medievalism, exacerbated by Evola’s later indulgence towards extreme reactionary Catholics, continues to puzzle those who would have thought that the Renaissance Neoplatonists were closer to his ideals. Instead, he lumped the Renaissance together with the Reformation, the Enlightenment, Socialism, Communism, and modernity as part of the degenerative process.

During the first years of World War II, Evola turned to yet another tradition, that of Buddhism, and wrote one of his best books: The Doctrine of Awakening: A Study on the Buddhist Ascesis. Just as with his early work on Tantra, Evola had to base his study on translations by English, German, and Italian scholars. Yet his insights into the human condition that Buddhism addresses, and the calm spiritual height from which it speaks, transcend mere erudition. The temporary habitation of Oriental modes of thought seems to have enabled him to forget the politics and the polemics which the modern West so easily provoked from him. At the same time, the work is revisionistic in its preference for Theravada (or Hinayana) Buddhism. The Western impression of Buddhism, abetted by nineteenth-century incomprehension and by Theosophical influence, has always been condescending to the primitive Hinayana (the word means “lesser vehicle”) in comparison with the “greater vehicle” of Mahayana Buddhism, to which belong the schools of Japan and Tibet that have been more successful exports. To Evola, the contrary was true: the Mahayana was a late and decadent development, sullying the original purity of Buddha’s philosophy with its sentimental and religious accretions (just the sort of thing Westerners would prefer!), while the uncompromising Hinayana was the original teaching, fit only for Aryas, i.e. the elite, in terms of their spiritual race. For a long time The Doctrine of Awakening was the only work of Evola’s available in English. It appeared from Luzac, a London Oriental publisher, uniformly with a number of René Guénon’s works, thus giving many (including myself) their first taste of the Traditionalist school.8 De Turris’s book, cited above, tells of Evola’s correspondence with the young translator Herbert Musson: a patrician Englishman who ended his life as a Theravada Buddhist monk.9

The trauma of Evola’s war-injury on 21 January 1945 and the years-long search for a cure left him permanently disabled. This is how he described his condition in a letter to a fellow philosopher: “The last war made me the gift of a lesion in the spinal cord, which has deprived me almost entirely of the use of my legs: a contingency, however, to which I do not attach much importance.” After almost six years of treatment in Austrian, Hungarian, and Italian hospitals, he returned to the apartment at 197 Corso Vittorio Emanuele II which he shared with his mother until her death in 1956, and whose owner, an aristocratic admirer, allowed him a free lease for life.

The postwar climate was not favorable to Evola, who bore the stigma of having backed the losing side. Now that “fascism” had become a term of abuse, it was applied to him, who had never joined the Fascist or any other party, indeed who had risked much with his criticisms of the government.10 It was difficult for him to resume the career as a journalist which had supported him before the War. He first returned to print with a thorough recasting of his early book on Tantra. Then he was rediscovered by some who were still faithful to the principles of the Right, and for them he wrote the booklet Orientamenti (“Orientations”).

Evola paid dearly for this act of idealism. A week after his return to his Roman residence on May 18, 1951, he was arrested and accused of being the “master,” the “inspirer,” with his “nebulous theories,” of a group of young men, who were accused in their turn of having hatched organizations for clandestine struggle and attempted to reconstitute the dissolved Fascist party.11 Evola, confined to his wheelchair, was held in the Regina Coeli prison until the trial, which lasted from early October until 20 November 1951, when he was acquitted.12

In the early 1950s Evola was still hoping for some counter-revolutionary movement, somewhat in the spirit of the “Conservative Revolution” of post-World War I Germany, that would restore the Right to power. Gli uomini e le rovine (literally, “The Men and the Ruins”), a book largely about public, social and political matters, addresses the potential leaders of such a movement. It is an analysis of the postwar world, somewhat like an updating of Revolt Against the Modern World, that ends with an outline of what would be needed for the healing of Europe: a Europe that would no longer be the playground and victim of the rivalry between the USA and the USSR Evola hoped – but knowing that it was probably beyond hope – for a resurgence of the Imperial ideal, which would endow the separate nations with a spiritual unity, but not with a forced, political one. His description of how Europe should not become united is an uncanny anticipation of what would, in fact, transpire. For example, he writes: “Democracy, on the one hand, and a European parliament that reproduces on a larger scale the depressing and pathetic sight of the European parliamentary systems on the other hand: all this would bring ridicule on the idea of a united Europe.”13 In the end, he puts his faith in the foundation of an Order, if among the ruins there are sufficient men left to stand up and constitute one.

Evola published no more books for five years after Men Among the Ruins. That his thought did develop is clear. The next time he addressed the elite, he no longer envisaged any possibility or desirability of changing the world itself: it was too far gone on the road to perdition and the conclusion of its cycle. The only place for revolution was now inside oneself. The title of the work in question, Ride the Tiger, refers to a Taoist emblem of how the superior man behaves towards a chaotic world: following the principles of “actionless action” and of “doing that which is to be done,” he uses it to fortify his own higher individuality. In contrast to the public themes of Men Among the Ruins, Ride the Tiger treats more private domains such as existential philosophy, belief and non-belief, sex, music, drugs, and death, always in the spirit of Tradition and from the point of view of their use for the man in quest of his Absolute Individual.

of Sex) by Julius Evola

The sexist language used here is deliberate, for Evola does not seem to have considered woman as a likely candidate for the quest. He had ample heterosexual experience, especially in his earlier years, but his anti-bourgeois principles caused him never to marry or have children. His book of 1958, The Metaphysics of Sex, anticipated the sexual revolution of the 1960s with its assumption that sex was not primarily given us for reproduction. It has always been one of the secret weapons in the magician’s cabinet; but Evola was the first, and to date the only writer to treat sex from the point of view of “traditional” metaphysics, so as to explain why it has this function.

Most of Evola’s remaining titles are anthologies of his earlier articles and journalistic essays on various subjects – genres to which he contributed prolifically up to his death.14 Only two more original books appeared: an autobiography, The Path of Cinnabar, and the provocatively titled Fascism, Seen from the Right:15 his verdict on the Fascism and National Socialism that had been, and will always be, the first thing with which his critics associate him. More importantly, he returned to the Ur and Krur materials which he had been working on since the war years, and gave them definitive form in 1971 as the three-volume Introduzione alla Magia (“Introduction to Magic”). This monumental collection, with its contributions from a dozen authors beside Evola, shows that the Italian strain in modern esotericism was in no way inferior to the French Martinist and occultist strain, or to the much-studied Order of the Golden Dawn. It remains for the other leading lights, notably Giuliano Kremmerz and Arturo Reghini, to gain equal recognition for their stature as thinkers and movers.

The fact that so much of Evola’s enormous output of books and articles has been reprinted bears witness to a stratum of readership to which there is no parallel in the Anglophone world, and whose influence as a ferment within political, cultural and academic circles, especially in Italy, cannot be ignored. In the first version of this essay I concluded that, “Evola is currently the only esoteric and magical philosopher to have any impact whatever on the ‘real world’.” That was after centennial conferences in Milan and Rome (1998) and a wave of other commemorations and publications had brought Evola into the public eye, synchronously with the rise of right-wing political parties such as the National Alliance and the Northern League. Whether anything came of it is for historians to judge.

Now there are rumors of Evolian influences at the highest level of government in both Russia and the United States. One agent named is Alexander Dugin, a known admirer of the Traditionalists, whose Eurasian theories and possible influence on President Vladimir Putin’s policies have often been mentioned in this magazine. The other is Stephen K. Bannon, strategist and assistant to US President Donald Trump. In 2014, addressing a Vatican conference via Skype, Bannon mentioned that Putin has an adviser “who harkens back to Julius Evola and different writers of the early 20th century who are really the supporters of what’s called the traditionalist movement, which really kind of eventually metastasized into Italian fascism.”16 Some of his Roman listeners may have gasped at this off-the-cuff revision of history, but three years later it sent the journalists googling the unfamiliar name, and to Evola’s posthumous “fifteen minutes of fame” through exposures in the New York Times and other unlikely venues.17

A lot of dots would need to be connected before any causal link could emerge between Evola’s political and spiritual philosophy and the presidency of Donald J. Trump. First, Bannon was speaking about Putin’s advisor, not Trump’s, and hardly with approval, since in the same speech he stated that Putin ran a kleptocracy and was intent on expanding the Russian empire. Second, that the Traditionalists “inspired Fascism” is doubly inaccurate: the Fascist movement was underway while Guénon was unknown in Italy and Evola still dabbling in Dadaism. When Evola did turn to political journalism after the Gruppo di Ur had dissolved, it was to criticize the Mussolini regime’s deviance from the principles of the true Right. For him this meant a monarchic, organic state, rather than one based on competing parties (as in democracy) or on class warfare (as in communism). Third, any serious student of Evola knows that in his riper and wiser years he adopted the position of apoliteia (detachment from politics). In Ride the Tiger he reflected on the futility of the “rectifying, political action” that had still seemed a possibility in Men Among the Ruins. The context was now, in 1961, the Cold War, and while admitting that life was more comfortable on the capitalist side of the wall, the conflict mattered little to the differentiated man, whose “inner imperative” could only be to retire from the public arena. As for the latter, Evola now said with devastating scorn that “even if leaders worthy of the name were to appear today – men who appealed to forces and interests of a different type, who did not promise material advantages, who demanded and imposed a severe discipline on everyone, and who did not prostitute and degrade themselves just to ensure a personal, ephemeral, revocable, and formless power – they would have almost no hold on present society” (pp. 173-74). Perhaps this introduction will help to clear the air and indicate where the true value of Evola’s work lies, encouraging some readers to explore it first hand.

An earlier version of this article appeared in TYR: Myth—Culture—Tradition, vol. 1 (2002), pp. 127-142, titled “Julius Evola: A Philosopher for the Age of the Titans.” It is adapted by kind permission of the Editors of TYR, on which more information can be found at Dominion Press.

English translations of Evola’s principal works, published by Inner Traditions in Rochester, Vermont, USA unless otherwise indicated: The Doctrine of Awakening, Eros and the Mysteries of Love (formerly The Metaphysics of Sex), The Hermetic Tradition, Introduction to Magic (by Evola and members of the Gruppo di UR), Meditations on the Peaks, Men Among the Ruins, The Mystery of the Grail, The Path of Cinnabar (Integral Tradition Publishing), Revolt Against the Modern World, Ride the Tiger, The Yoga of Power.

Footnotes

1. See end for a list of Evola’s major works available in English. The original version of this article contained a full documentation of sources, both original and translated, and other notes, omitted here. Much information, complementary to the present article, can be found in Gwendolyn Toynton, “Mercury Rising: The Life and Writings of Julius Evola,” New Dawn 111 (2008): 63-68.

2. Yet after World War II he was commonly addressed as “Dr.” or even “Prof.” The false identity he assumed in Austria was that of a Graf [Count] von Bracorens. See Gianfranco de Turris, Julius Evola: Un filosofo in guerra 1933-1945 (“Julius Evola: A Philosopher in Wartime 1933-1945,” Milan: Ugo Mursia editore, 2016), 96, 202, 214.

3. Evola, letter to Croce, 13 April 1925, quoted in Piero di Vona’s introduction to Teoria dell’Individuo Assoluto (Rome: Edizioni Mediterranee, 1998), 7-8.

4. A favorite metaphor of Evola’s: each of us enters the world with a more or less difficult “equation” which it is our life’s project to “solve.”

5. For more on this subject, see J. Godwin, “When Does the Kali Yuga End?” New Dawn 138 (2013): 63-68.

6. Thomas’s book, Julius Evola e la tentazione razzista: L’inganno del pangermanesimo in Italia (“Julius Evola and the Racist Temptation: The Deception of Pangermanism in Italy,” Mesagne: Giordano editore, 2006) has not appeared in English. The foregoing passage quotes from my combined review of that book and of Evola’s autobiography in TYR, vol. 4 (2014): 329-42.

7. The reasons were analyzed by Piero Fenili in a series of articles in the periodical Politica Romana. These, too, are only accessible in Italian. I have summarized their arguments in an article “Politica Romana pro and contra Julius Evola,” in Arthur Versluis, Lee Irwin, and Melinda Phillips, eds., Esotericism, Religion, and Politics (Minneapolis: Association for the Study of Esotericism, 2012): 41-58.

8. For a balanced evaluation, see J. Godwin, “Understanding the Traditionalists,” New Dawn 147 (2014): 63-69.

9. See Musson’s biography at obo.genaud.net/backmatter/gallery/nanavira.htm

10. In this as in many other regards, Evola resembles the anti-Nazi novelist Ernst Jünger.

11. How reminiscent of the accusations against Socrates: misleading the young, and not believing in the gods of the city but in other, strange gods!

12. See J. Evola, Self-Defence, published as an Appendix to Men Among the Ruins (see list of works).

13. Men Among the Ruins, 278.

14. Meditations on the Peaks (see list of works) is one such collection.

15. Il fascismo, saggio di una analisi critica dal punto da vista della Destra (“Fascism, Essay of Critical Analysis from the Point of View of the Right.” Rome: Volpe, 1964). The second edition (1970) is enlarged with Note sul Terzo Reich (“Notes on the Third Reich”).

16. Quoted from the website www.buzzfeed.com/lesterfeder/this-is-how-steve-bannon-sees-the-entire-world and the audio recording linked thereto.

17. See Jason Horowitz, “Steve Bannon Cited Italian Thinker Who Inspired Fascists,” New York Times, Feb. 10, 2017.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.