From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 12 No 2 (Apr 2018)

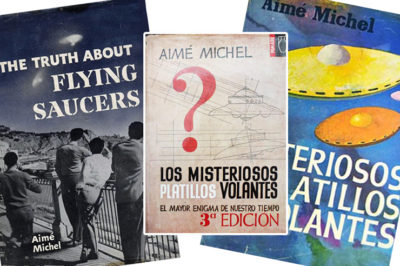

Aimé Michel, who died in 1992, was certainly the most memorable French UFO researcher and a pioneer in this field. In the early 1950s he wrote the second French book on the subject, Lueurs sur les soucoupes volantes (published later in English as The Truth About Flying Saucers by Criterion Books, NY). He was the only one who was successful in putting some rationality into the irrationality that is the UFO phenomenon.

In 1954, he was 35 years old and worked at the French Radio and Television Broadcasting. Since the end of August, France had been literally invaded by “flying saucers.” Every day they were making headlines in the daily press. For instance, the classic case at Vernon near Paris on 23 August where one of the witnesses, Bernard Miserey, observed a huge red-orange cigar-shaped object releasing several smaller luminous craft above the Seine river; or the well-known case of the landing of a bell-shaped UFO with two little cosmonaut-looking entities experienced by Marius Dewilde on 10 September at Quarouble in the north of France, to mention only two.

One day in the fall of 1954 during a dinner, his friend Jean Cocteau (1889–1963), who had read his first book The Truth About Flying Saucers, gave him the following advice:

“You should search if all those flying saucers did not obey some order which our eyes, at first glance, could not suspect. It would be necessary to see if these objects move along certain lines, if they describe some drawings, or anything? You could see, for example, if there are coincidences between their routes and the earth magnetic lines, or other lines with any meaning possible.”

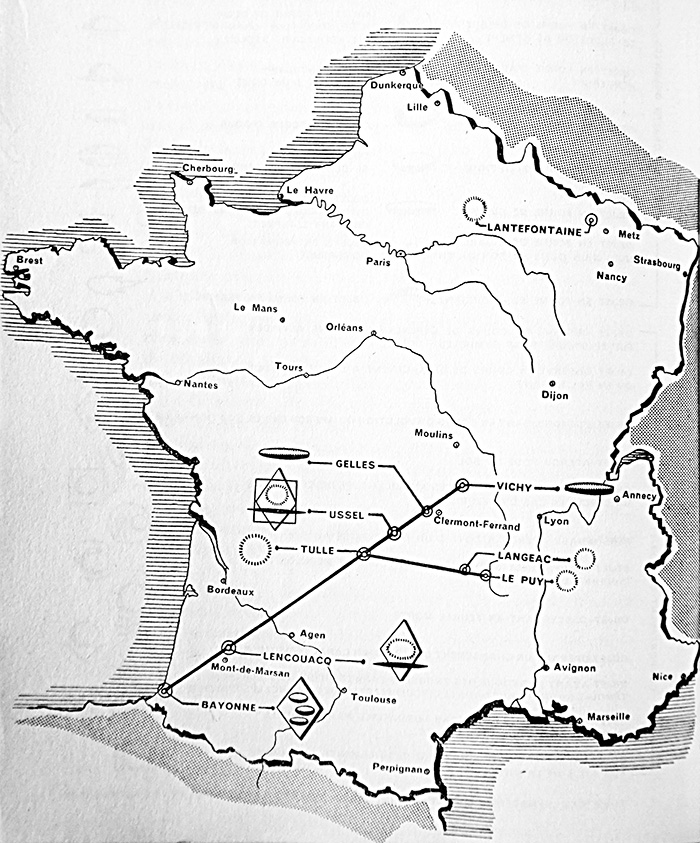

The word was out: “lines…” And it was to lead Aimé Michel towards his main contribution to Ufology, the “orthoteny.” Michel began plotting on large Michelin maps of France all the sightings of the wave of 1954. Wholly unexpected spider web-like figures appeared. In a program on UFOs, broadcast on French TV in 1965, he alluded to one of the most puzzling “alignments” he discovered.

“And doing so I found rather surprising things. For example, on September 24, 1954 there were… nine observations which had been reported to me, which I had found in the press or which had been sent to me by correspondents. These nine observations were located respectively at Lantefontaine in Lorraine, at Langeac, at Le Puy in the Massif Central and then at Vichy, at Gelles, at Ussel, at Tulle, at Lencouacq and at Bayonne. All this in the southwest quarter of France. Yet …one realises that out of nine there are… six which are strictly aligned… and when I say ‘aligned’ it must not be assumed that it is an approximate alignment, not at all, it is something extraordinarily precise.”

He reported all his discoveries in his second book on UFOs, Mystérieux Objets Célestes (Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery, Criterion Books, NY), published in 1958, which deals exclusively with the big French UFO wave of 1954. The word, “orthotenic,” coined by Michel, is derived from the Greek adjective “orthos,” meaning straight. Following Cocteau’s line of thought, he had indeed brought to light the tendency of UFO sightings to fall in several straight lines over a period of about 24 hours. The book included beautiful maps (some unfoldable) detailing the daily crisscrossing patterns of lines. Regularly where those orthotenic lines crossed, a big vertical cigar-shaped UFO, some would say a “mother ship,” was observed.

Ufologists of today cannot imagine the revolution it was, not only in France but all over the world. At last one started to find some “order” out of this festival of absurdity… The laws of orthoteny were born and every ufologist would have his map in his bedroom trying to find new “alignments” or to confirm those already discovered like the famous 24 September 1954 Bayonne-Vichy line (BAVIC) with its 6 observations.

Then a few years later came the dream-breakers. It was the computer scientist and ufologist Jacques Vallee who first began to undermine the theory of his “friend” Aimé Michel. From analysis using computers, he concluded that “among the proposed alignments, the great majority, if not all, must be attributed to pure chance.” (Vallee, Challenge to Science, Henry Regnery Co., Chicago, 1966). Then another fellow countryman, the ufologist Jean Sider, years later, in his book The 1954 File and The Rationalist Imposture (ed. Ramuel), put the last nail on the coffin, suggesting that Michel had some of his dates wrong.

In his 2000 book, UFOs: The Mechanisms of Disinformation (Ovni: Les mécanismes d’une désinformation, ed. Albin Michel) a friend of Michel, the great professional astronomer and astrophysicist Pierre Guérin (1926–2000), who advocated an extra-terrestrial origin for UFOs, wrote this:

“To say that Aimé Michel took with good heart the failure of the orthoteny [concept], which was his discovery and about which he had fully committed himself, would be a lie. He accepted it only with reluctance and bitterness. It was a subject he did not like to speak about. But, nevertheless, a deserved tribute must be paid to this thinker for having tried an impersonal scientific approach of the UFO problem.”

Among the other contributions to Ufology, Michel was the first one to discuss many now “classic” cases such as the famous Oloron and Gaillac “flying saucer-angel hair” sightings from 1952, or, in the same year, the Marignane Airport case, the first landing case reported in France.

As far as I am concerned, I remember him as being the first person to be interested and publish the UFO photos taken near Lake Chauvet, right in the centre of France.

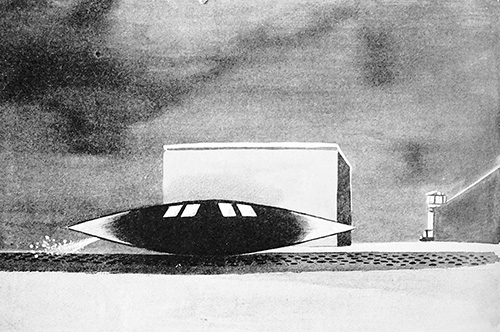

This remarkable observation was made by an electrical engineer, André Frégnale, on 18 July 1952, at 6:10 p.m. While looking southward, he noticed in the sky a disc-shape object coming from the west. The trajectory was “horizontal and rectilinear,” the linear speed “uniform” and the regularity of pace “impressive.” The object moved in absolute silence. Frégnale seized the camera he had with him, a 24 x 36 Zeiss Ikon equipped with a 45mm objective, and took four photos. When the “mysterious machine” was too far away to be photographed, he took his binoculars to follow the object which was travelling away, and saw it disappear, almost immediately, as if it had vanished on the spot.

All in all, the observation lasted not much more than one minute. In 1954, two of the four photos were published for the first time in Aimé Michel’s book The Truth About Flying Saucers. Over the years these four photos were carefully analysed, notably by Pierre Guérin in his book UFO: The Mechanisms of Disinformation, who had definitively excluded the hypothesis of a model or of a craft of terrestrial origin. So, to this day, the object remains unidentified.

Disappointed by the reaction of the ufological community and probably weary of several back-stabbings, Aimé Michel would later focus less on the UFO enigma. He wrote mostly about animal life, philosophy and mysticism, and I should say Catholic mysticism, for instance in many articles for the magazine France Catholique. We can feel in these articles the influence of his friend Jean Cocteau. Each article is written with great style, nearing somewhat the poetic style. Aimé Michel was above all a poet writing in prose. I would define his book Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery as a work of a poet using scientific tools – a work of a man “radiating intelligence,” as Jean Cocteau said about him in a letter, who “always goes farther than the farthest and this without the slightest vagueness.” That’s why his UFO books, and Flying Saucers and the Straight-Line Mystery in particular, will not die; you can read it for the style of the writing, for the subtle poetry that permeates it, as well as for the clarity allied with the depth of the ideas expressed.

His third and final book dealing with UFOs came out in 1969, Pour ou contre les soucoupes volantes (For or Against the Flying Saucers). This book, published by the editions Berger-Levrault, was co-authored. Michel wrote the 77-pages of the “For” part, and the aeronautical engineer Georges Lehr, playing the role of sceptic, the 75-pages of the “Against” part.

Aimé Michel died at 73 years of age in his small village of Saint-Vincent-les-Forts at the feet of the Alps, where he was born and had lived most of the time. Nature and mountain lover, his very first book in 1953, Heroic Mountains, was actually a history of mountaineering and of its heroes. The “flying saucers” had not yet entered his life.

The author thanks Warren P Aston for editing this article.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.