From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 7 No 3 (June 2013)

It is noon on a summer morning in California, and I am sitting in a dimly lit auditorium that is decorated in an Egyptian style with Art Deco touches. A group of us have shuffled in and taken our seats on finely polished wooden benches, and we are led on a guided meditation.

I don’t remember the exact content of the meditation, but I do remember the inner experience it generated in me. I had a strong sense of being in an Egyptian temple, seated on a stone chair on a stone dais in the centre of a room. The room had some kind of indirect lighting, and the only image I saw on the walls is a winged disk in front of me. Within me was a sense of coolness and centredness. I also had a slight glimpse, through a side entrance, of a bright blue sky with desert sand and some palms. I went into a deep meditative state and came out of it when the session ended.

The setting I was in – I mean in the physical world – was the temple of the Ancient and Mystical Order Rosae Crucis (AMORC for short) in San Jose, California. It’s not surprising, perhaps, that I should have a sense of Egypt – the entire property, Rosicrucian Park, which occupies a city block, is designed in a quasi-Egyptian style – but it is surprising that the sense of Egypt should be so powerful. Later I realised I had had a much stronger feeling of being in ancient Egypt during that meditation than I had ever had when I visited the country itself.

AMORC was founded in 1915 by an American ad man named Harvey Spencer Lewis, who received certain initiations in the Rosicrucian tradition in Europe around 1910. Using American marketing techniques (such as advertising in magazines), he built AMORC into one of the largest and most visible esoteric orders in the world. And, he insisted, the lineage of this tradition went back to Egypt itself.

Does it? How could we possibly know? The amount of documentation that would be required to prove such a claim would be enormous, and anyway such materials would hardly be able to survive the assaults of the millennia.

I am not a member of AMORC myself – I was present for that meditation, and a couple of others like it, while I was attending a conference sponsored by the organisation in July 2010. Moreover, I’ve never felt any great affinity for ancient Egypt. I have no way of knowing whether my experience arose from a contact with a thought-form built up by decades of Rosicrucian practice or whether it genuinely conveys a living tradition that goes back to the days of the pharaohs.

The “Upper Room”

Perhaps it does not matter. In either case this experience suggests one characteristic of an esoteric order: it must have an “upper room.” The phrase goes back to the New Testament, which tells of Christ’s disciples gathering in an “upper room” after his ascension (Acts 1:13). The phrase also appears in Mark 14:15 and Luke 22:12, which speak of an “upper room” at which the Last Supper was to be held. The detail is striking: what difference does it make if you meet in a room that is on an upper storey rather than a lower one? In a literal sense, none; but in an inner sense, I believe that an “upper room” – that is, a place on an astral level, as it is sometimes called, or the realm of the psyche – is a necessary part of an esoteric order. This “room” can be created by the sustained work of visualisation by a group over a certain period of time, and after a certain point it can start to have a quasi-independent existence. The group can gather there in thought, if not physically. This kind of “upper room” may be what I glimpsed in my AMORC meditation.

Curiously, one of the requirements given for the brothers in a seventeenth-century text known as the Fama fraternitatis (“Rumor of the Brotherhood”), a chief inspiration for the Rosicrucian movement, is “that every year, on the day C., they should meet together at the house Sancti Spiritus [of the Holy Spirit], or write the cause of his absence.” It is not clear which exactly is the “day C.,” but there is some evidence, at least in certain strains of the Rosicrucian tradition, that, despite the difference in initials, it is the feast of the Epiphany on January 6. (I do not know if this is the case for AMORC.) In any case, it seems likely that “the house Sancti Spiritus” is not a physical building, but the kind of upper room that I have been talking about here.

None of this, of course, tells us exactly what an esoteric order is, so some explanation is needed. Let’s begin by assuming that there is a vast continuum of development in consciousness, from the most ephemeral subatomic particle to beings and dimensions greater than we can conceive. Let’s also assume that the realm of human life and consciousness forms a very narrow bandwidth on this enormous span. There are levels below us and above us. Moreover, these levels are not rigidly separate or discrete, but blend into one another, like the colours on the visible spectrum. That is, there is some communication among them. The most famous image of this process appears in Jacob’s dream in Genesis: “And behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it” (Genesis 28:12).

We might go on to make another assumption – that the interaction that takes place among these levels involves a certain degree of responsibility, that the level above is required to help the one below rise to a higher degree of consciousness. Taking all these possibilities into account, we have a sense of what esoteric orders might mean for human development.

By this view, there are beings who have a greater degree of awareness (and, we may hope, compassion) than we do. They are aware of us – dimly, perhaps, as we are aware of them – and are able to help us. But in fact we cannot see these beings on a physical level. They exist on some other plane, and we need to rise up to that plane in order to have some genuine communication with them.

Hence the need for an upper room. Hence also the need for a group or community that can train people to rise to this upper room and have some communion with the beings there. (The Jewish Kabbalists sometimes refer to this as “the academy on high.”) These groups would constitute the esoteric orders – some of them known but many, perhaps most, unknown to any but their own members. The esoteric orders would exist on the physical level, but they would also have contacts on levels above. These are sometimes called “inner plane” contacts.

To take another example – again from a group that I do not belong to – there is the little-known Esoteric School of Theosophy. The Theosophical Society (TS) itself is comparatively well-known. It was founded in 1875 by the Russian savant H.P. Blavatsky and several of her associates. Today it continues to function on a worldwide basis as a means of, among other goals, investigating the “unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity.” The TS is said to have been inspired by Blavatsky’s contact with certain Masters or adepts who possessed paranormal powers and whose mission was to elevate the spiritual state of humanity.

As the TS grew and spread, its purpose became more diffuse, and it attracted many members who were interested in studying about but not necessarily pursuing the esoteric path. Consequently, in 1888 Blavatsky formed what she called the “Esoteric Section” of the TS, which was more oriented toward practice. Later the name was changed to the “Eastern School of Theosophy,” and finally to “the Esoteric School of Theosophy,” an organisation that exists to this day. It is not a secret society per se, but it is comparatively discreet about its existence and is only open to members of the TS. Those who want to join the Esoteric School must pledge themselves to a life of purity, eschewing meat, alcohol, and sexual license. (Not all esoteric orders have these requirements.) Members of the ES, as it is known for short, also devote themselves to lives of study, meditation, and service, although they do not withdraw from the world as monks or nuns.

Part of the goal of the ES seems to be to maintain contact with the Masters or adepts of whom Blavatsky spoke. I do not myself know what the nature of this contact is, if it is genuine, or which Masters the members of the ES would claim to be in touch with. Nor do I know whether these Masters are believed to be living in physical bodies or exist only on the inner planes. I have occasionally put questions about these things to members of the ES but have only gotten vague and noncommittal responses. Nonetheless, this contact seems to be part of the task of the ES, and it helps illustrate the purpose of having an upper room.

Initiation

Esoteric orders usually bring in new members through initiation. The word “initiate” is in some ways a misleading one. To some, it connotes someone who is highly advanced – as, for example, in Cyril Scott’s Initiate trilogy of occult novels from the 1920s and ’30s, whose hero, Justin Moreward Haig, displays astonishing paranormal powers. But the core meaning of the word is really “beginner” – an initiation is a beginning. Initiation can take many forms and can range from the extremely simple to the extremely complex, but often it contains a sequence of acts in which the initiate symbolically “dies” and then is resurrected in a new and transformed state. The most familiar version of this rite is Christian baptism, particularly in its original form, whereby the candidate is fully immersed in water. By this symbolic drowning and restoration, the new Christian takes part in the death and resurrection of Christ himself. (Christianity today, of course, is not an esoteric order, but there is some evidence that it began as an esoteric order and was later popularised.)

The Catholic Church has traditionally taught that the rite of baptism leaves an indelible mark on the soul, removing all sin. Writing on the occult significance of the sacraments in the early twentieth century, the Theosophist and clairvoyant C.W. Leadbeater was more cautious in his assessment. While saying that it was “distinctly… an act of white [beneficent] magic, producing definite results which affect the whole life of the child,” he also pointed out that “a Sacrament is not a magical nostrum. It cannot alter the disposition of a man, but it can help to make his vehicles a little easier to manage. It does not suddenly make a devil into an angel, or a wicked man into a good one, but it certainly gives the man a better chance. That is precisely what Baptism is intended to do, and that is the limit of its power.”

As this passage suggests, initiatic practices usually intend to transform the inner nature of an individual. The Freemasons sometimes claim that the aim of their secret initiations is “to make good men better.” This is generally a subtle process, and probably for most individuals the change they undergo is comparatively gradual and difficult to see unless you are looking for it. In some cases, however, initiation produces more dramatic effects.

Over twenty years ago, when I was editor of Gnosis, a now-defunct magazine of the Western inner traditions, I entered into correspondence with a gentleman from Jordan named Dr. Jamal N. Hussain, who was researching deliberately caused bodily damage (DCBD) phenomena. He told me about the Tariqa Casnazaniyyah, a Sufi order whose name means “a path that is known by no one.” (For a discussion of the Casnazaniyyah order, see ashraf786.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=sufi&action=display&thread=23998.)

This order, which traces its lineage back to the Prophet Muhammad, has a membership said to number in the millions, located chiefly in Iraq, Turkey, Iran, and Jordan. Its initiation process is quite simple. It consists of a brief two- or three-minute ritual in which the initiate recites a vow while exchanging a ritual handshake with the master of the order or one of his deputies. The initiate then requests permission to perform certain types of miracles. The master grants permission on the condition that the initiate will perform them only to attest to the greatness of the Casnazaniyyah order.

After this initiation, the individual can pierce his body with sharp objects, swallow razor blades, eat poisonous scorpions, or handle fire, all without any apparent harm. Scientific explanations are difficult to come by. As Dr. Hussain pointed out, this effect cannot be explained by endorphins (the body’s natural painkillers), since the wounds heal spontaneously and immediately. Nor can it be explained by self-hypnosis, since the practitioners do not experience any altered state of consciousness. While I myself have never witnessed any of these phenomena, Dr. Hussain did send along a number of rather poor-quality Polaroid photos, which did not seem to be doctored. In one of them, a bare-chested man with a large belly was piercing himself with spikes. In another memorable image, a man was chomping down on a scimitar, which was cutting into his lips. Dr. Hussain invited me to a conference in Baghdad that was discussing DCBD phenomena, but I was unable to go.

No matter how exotic their manifestations may be, esoteric orders have the task of making and maintaining contacts with higher levels of consciousness and being, and inducing a transformation within their members that make this possible. A complementary task is to carry out some function in the world – to do some kind of work that furthers human advancement. For example, the monastic orders that grew up in late antiquity had the function of preserving the essence of classical civilisation in the wake of its collapse. They also cleared land for agriculture in Europe and managed it in a careful and responsible way, creating the foundations of Western civilisation. “In a sense they determined the whole history of Europe,” writes historian Paul Johnson; “they were the foundation of its world primacy.” As the Dark Ages passed and medieval civilisation flowered, the monasteries, having fulfilled their purpose, fell into corruption. Today the monastic orders still survive, but for the most part only as dwindling vestiges.

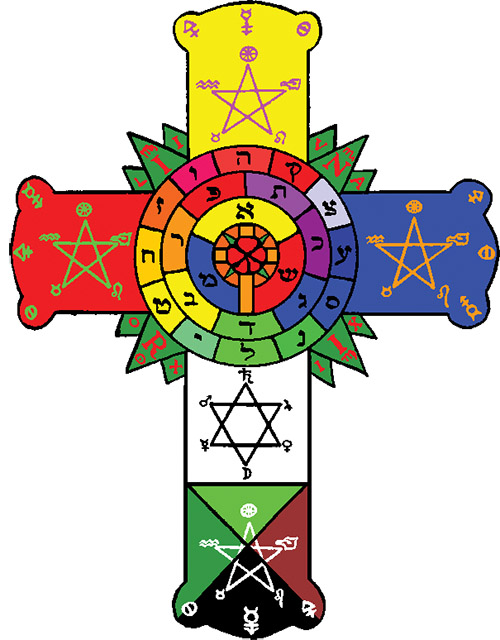

Some have tried to classify esoteric orders on the basis of their functions. In the 1990s the British esoteric school known as Saros came up with a twelvefold division, inspired by the verse in Revelation that speaks of “twelve gates” to the holy city (Revelation 21:12). The Saros schema comprises Teachers, Prophets, Magicians, Lawgivers, Traders, Artists, Craft Workers, Life Tenders, Warriors, Perpetuators, Priests, and Explorers. One can easily find examples of these in world history: the schools of the prophets or “sons of the prophets” under such figures as Samuel, Elijah, and Elisha (1 Samuel 10:11; 19:19–20; 2 Kings 2:3, 5; 4:38; 6:1); the military orders of medieval times such as the Templars and Hospitallers; and the various magical orders that have arisen in the West over the past century or so, like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

System of the Seven Rays

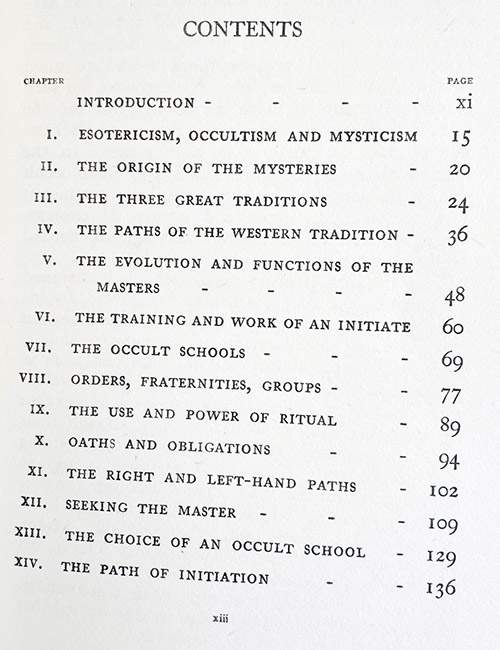

In fact one of the most illustrious pupils of the Golden Dawn, Violet Firth, writing under the pen name Dion Fortune, wrote what is probably the best introduction to the subject: The Esoteric Orders and Their Work, which was originally published in 1928. Dion Fortune categorises the orders of the West according to a system of the Seven Rays that is similar to the one found in Theosophical teaching. Her schema is worth looking at in some depth.

Beginning with the seventh ray, Fortune contends that this, “the Plane of Abstract Spirit,” cannot be contacted while in the physical body. Instead the higher Self must withdraw, leaving the body in a trance. Fortune says that this seventh ray is not highly developed in the West, being characterised for the most part by mystics and ecstatics; Teresa of Avila is one of the principal sources on the subject. This ray is not to be developed prematurely, before the other, lower ones have been brought to fruition; otherwise it produces a kind of spiritual inertia. The school of the Quietist mystics in seventeenth-century France and Spain offer an example of this problem. Hence orders of the seventh ray are chiefly to be expected in the future.

The sixth ray is connected with spiritual devotion, with what the Hindus call bhakti, and, Fortune says, “hereon are developed the spiritual qualities of Love, Truth, Goodness, Purity, and many others.” It is headed by the Master Jesus, she says, and hence is known as the Christian Ray. “It is the hidden power of Christianity which was taught to the disciples in the Upper Room whilst the multitude received but a rule of life – a rule, however, which if faithfully followed, would bring them to that Upper Room where they could receive the inner teaching.”

The fifth ray is connected with the use of abstract reasoning. Fortune says it is called the Pythagorean Ray because it reached its heyday in the mystery schools of ancient Greece, among which the Pythagorean school was prominent. For the philosopher Pythagoras, who lived in the sixth century BCE, the universe was grounded in the principle of number and hence was knowable mathematically.

The fourth ray is the ray of concrete, as opposed to abstract, mind; its quintessential master was the semimythical sage Hermes Trismegistus, and it bore fruit in the Egyptian and Chaldean mysteries of antiquity, as well as in its heirs, such as Gnosticism and the Jewish Kabbalah in late antiquity, as well as in the alchemists of medieval and early modern times. The Rosicrucians of AMORC, with their strongly Egyptian flavour, might come under this ray.

The third is the ray of beauty and harmony; “being an initiation of the emotions, its standards of value are aesthetic, not ethical.” It was exemplified by some of the earlier Greek mystery schools, Fortune says, particularly those of the Dionysian cult. Later it gave rise to the “Celtic racial culture” and hence is known as the Celtic Ray. It seeks to embody beauty and harmony in the manifestations of physical reality, and as a result is also known as the artist’s ray.

The second, “the Norse Ray,” is so called “because the purest contacts of this much-corrupted tradition which are available to us in the West are those of the Nordic mythology.” It deals with the plane of primitive instincts and the urge to overcome them; its ecstasy arises out of courage – the sublimation of fear in battle. Its dark side is cruelty, as can be seen from the ancient Viking practice of the “blood eagle,” in which a victim (usually a prisoner of war) had his rib cage cracked open from behind; his lungs were then ripped out and spread out on his back, producing a ghastly imitation of a pair of wings. Fortune suggests that this ray reached its zenith in remote primitive times.

The first ray principally involves the mastery of the physical body. The Casnazaniyyah order forms a rather extreme example of this type. Dion Fortune says that this ray is not “worked” in the West in the present day; and it probably was not in her time (she died in 1946), but we can see its resurgence on the contemporary scene with the wide popularity of hatha yoga. Although Fortune does not say this, it can probably be connected with the health and fitness cults of recent generations.

I must add here that Fortune’s picture of the seven rays is not quite identical with those of the classic Theosophical view (as outlined in, for example, Ernest Wood’s 1925 book The Seven Rays), but it remains comprehensive, particularly in trying to account for the different strains of the Western esoteric traditions. Again, it is easy to find examples of these different rays in many esoteric schools worldwide, whether we look at the way of the fakir or sadhu as practiced in the East (first ray) or at the schools of icon painters in Greek and Russian Orthodoxy (third ray). Other orders are more difficult to categorise. One would have to know more about the goals of the Esoteric School of Theosophy to be able to decide under which ray it fit.

For this reason at least, I would not view Fortune’s schema, or any other, as fixed and absolute. As usual, they provide categories for classifying and thinking about a certain area that remain useful as long as they do not form rigid conceptual barriers in the mind.

Coming to the end of this article, a reader may wonder about a number of things often associated with esoteric orders that I haven’t mentioned. What about the elaborate rites and costumes, the dazzling insignia, the extravagantly august titles often given to the leaders? Where do these fit in? They are external appurtenances – the hard shell around the order’s living core. At best they serve as reminders and confirmations of the ideals that it pursues. But if the members become too preoccupied with these appurtenances and they grow too cumbersome, this hard shell thickens and kills the living pith within. Thus when many people think of esoteric orders, they are often thinking of former esoteric orders that have died and are only going through the motions. If a seeker is only interested in these externals, most likely he will be drawn to groups of this kind, and may find them perfectly congenial. In most cases they are probably harmless enough.

More than many other subjects in this field, esoteric orders retain an air of mystery about them. The vast majority are probably unknown to all but their own members, and the role they play in human history is subtle and hard to pin down. Some may focus heavily on their inner plane contacts, while for others these may be only felt as a vague and remote influence. But insofar as these groups foster human development and point us toward vistas that lie beyond the bounds of conventional reality, they continue to underpin civilisation in ways about which we can only guess.

Sources

Paul Foster Case, The True and Invisible Rosicrucian Order, Samuel Weiser, 1985

Dion Fortune, The Esoteric Orders and Their Work, Aquarian, 1982

Paul Johnson, A History of Christianity, Atheneum, 1987

C.W. Leadbeater, The Science of the Sacraments, 2nd ed., Theosophical Publishing House, 1929

Richard Smoley, “Sufi Order Practices Way of the Fakir,” Gnosis 31 (Spring 1994), 8-9

Ernest Wood, The Seven Rays, Theosophical Publishing House, 1925

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.