From New Dawn 170 (Sept-Oct 2018)

We like to think that modern science has developed as a result of rational enquiry; however, the history of science is littered with tales of bizarre experiments, eccentric characters and peculiar coincidences.

Many of the influential scientists responsible for the birth of modern science were not the conventional rationalists that they are often portrayed as. Although their discoveries are the result of complex mathematical workings and meticulous scientific experimentation, many of them were also heavily immersed in the esoteric world of the occult and pursued the mystical practices of alchemy, astrology and magic.

While the orthodox scientific community has denounced these practices as nonsensical pseudoscience, they are incredibly significant in the history of modern science.

This article examines three scientists who made exceptional contributions in their fields including the occult, showing the unusual and forgotten ideas that guided the course of scientific enquiry.

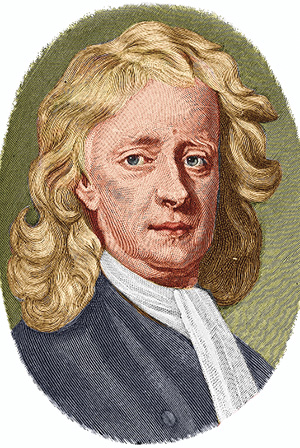

Sir Isaac Newton and the Philosopher’s Stone

Sir Isaac Newton is recognised as one of the most influential scientists to have ever lived and was a crucial figure in the scientific revolution during the Enlightenment period. Born in 1643, Newton is credited for developing the laws of modern physics; however, he also made discoveries in mathematics, optics, and other scientific disciplines.

His momentous book, Principia, brought him to international fame when published in 1687 and distinguished him as one of the most important scientific figures of the Renaissance. The manuscript contains information on the elementary principles of modern physics, such as the laws of motion and the theory of gravity. Newton is also credited for developing essential concepts of modern calculus, demonstrating his prodigal influence within both science and mathematics.

Newton’s historical legacy has come to symbolise the power of the scientific method in the development of Western civilisation, but many people are unaware that Newton was not a conventional scientist. He was a very curious individual who dabbled in the peculiar and unusual world of the occult, a realm antithetical to the narrow rationalism of science. In fact, after purchasing Newton’s manuscripts and studying his works, economist John Maynard Keynes famously stated that “Newton was not the first of the age of reason, he was the last of the magicians.”1

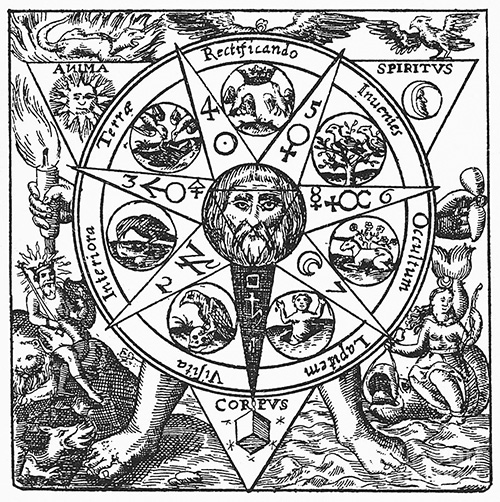

An area of the occult that Newton extensively studied was alchemy. Alchemy was the medieval forerunner to chemistry and outwardly concerned the transmutation of base metals into gold and the discovery of a universal elixir that would bless its creator with immortality. Grounded in the discipline of hermeticism, alchemy was not only a method of chemical transmutation but also a spiritual practice by which the alchemist sought to purify their body and soul.

Since chemistry was in its infancy during Newton’s lifetime, many of his studies in chemical science contained language more typically associated with occultism than modern science. Unfortunately, a laboratory fire caused by his dog may have destroyed most of his works, and therefore our understanding of how much he knew about alchemy is somewhat limited.

Existing works suggest Newton was heavily immersed in the hermetic discipline and his primary objective was to discover the philosopher’s stone, a mysterious substance that supposedly had the power to turn base metals into gold. The stone was central to the imagery of medieval hermetic philosophy and symbolised man’s attainment of spiritual perfection.

Newton’s writings suggest that he was interested in this mystical object and undertook many experiments to uncover its chemical composition. He also believed that ‘Diana’s Tree’, an alchemical process that produces a dendritic ‘growth’ of crystallised silver from a silver-nitrate solution, proved that metal “possessed a sort of life.”2

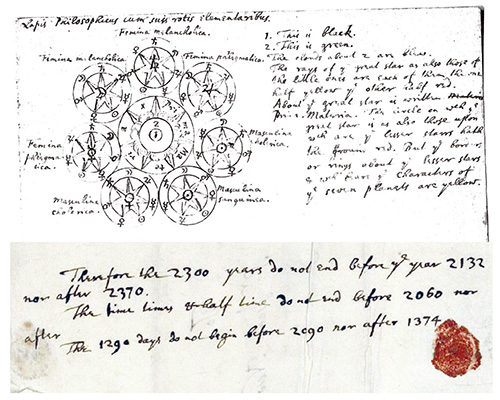

Newton was not only interested in alchemy. He also believed the Bible contained hidden information about a future apocalypse. Unpublished documents, evidently written by Newton, indicate he thought the world would end by the year 2060 AD based on a series of mathematical calculations. It has been suggested the apocalypse he was talking about was a transformative stage in mankind’s spiritual evolution in which the human race would achieve a higher state of transcendental consciousness; however, this is mostly scholarly conjecture.

The original documents written by Newton are currently stored at the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem. It appears that they were written for personal use since Newton personally disliked date-specific biblical prophecies. This would make sense considering he provided no actual date as to when the world would end, merely predicting it would happen before the year 2060. Newton’s reasoning behind this particular date cannot be considered in cultural and historical isolation. It must be understood in the context of his antitrinitarian beliefs and Protestant views on the Papacy. His writings suggest he relied on the specific chronology of events described in the Bible, as well as the ominous prophecies described in the Book of Revelation, to calculate the date. The religious basis for his calculations is evident when he writes:

“So then the time times & half a time are 42 months or 1260 days or three years & an half, recconing twelve months to a yeare & 30 days to a month as was done in the Calendar of the primitive year. And the days of short lived Beasts being put for the years of lived [sic for ‘long lived’] kingdoms, the period of 1260 days, if dated from the complete conquest of the three kings A.C. 800, will end A.C. 2060.”3

As one can see, Newton was of the belief that biblical scripture contained encrypted knowledge about the future of humankind’s destiny; he carefully studied the chronological dates and events described in the Bible and performed complex mathematical calculations to determine the date of the apocalypse. Although he made various predictions during his lifetime, he was certain that a global cataclysm would destroy Earth before the year 2060 based on his interpretation of the Bible.

Although Newton’s legacy has become associated with the development of modern science, he was deeply immersed in the esoteric practices of alchemy, hermeticism and biblical prophecy. While modern science denounces these practices as irrational and absurd, Newton’s interest in the occult suggests they played a more significant role in the history of scientific enquiry than we have been led to believe.

Galileo and the Art of Astrology

Galileo Galilei was a mathematician, astronomer, physician and engineer during the Italian Renaissance; he is considered to have been a central figure in the transition from natural philosophy to modern science.

Born in 1564, Galileo made a number of breakthrough discoveries in mathematics, optics and astronomy. In 1609, he heard about the invention of the spyglass, a device that made objects in the distance appear closer, and used mathematical knowledge to design the first working telescope. Galileo then made his first astronomical discovery when he cast the lens of his new invention upon the surface of the moon. He was also the first astronomer to observe the four moons of Jupiter, track the planetary phases of Jupiter and detect sunspots on the Sun.

Galileo faced fierce opposition from the Roman Inquisition since his writings promoted a heliocentric view of the universe in which the Earth rotates around the Sun. The Inquisition believed that this fundamentally questioned man’s central place within the cosmos and sentenced him on the grounds of heresy, resulting in indefinite imprisonment until his death in 1642. Ever since Galileo has become known as one of the most influential scientists to have ever lived. However, many people are unaware that he had an interest in mysticism and hermeticism as well as the mysterious world of the occult.4

Like many scientists during the Italian Renaissance, Galileo was well practiced in the art of astrology. Although the idea of astronomers practising astrology seems alien to us in the modern age, during the Renaissance period many early scientists believed that the position of planets and stars influenced man’s destiny. In fact, it has been suggested that scepticism towards astrology only emerged during the Enlightenment period, when scientists like Rene Descartes emphasised the importance of scientific doubt. Before then, astrological beliefs were deeply embedded across European culture, and members of the aristocracy relied on its predictive power to make important political and economic decisions.

The Medici Family, who ruled over Florence during the 15th century, would often appoint astronomers to interpret their horoscopes. When Galileo discovered the four moons of Jupiter in 1609, he told the Medici Family that fate had reserved the planetary objects for them so each of the family’s four sons would have one to their name. In fact, when Galileo revealed knowledge of the discovery in his book, Sidereus Nuncius, he decided to name them “Medici Sidera,” meaning the “Medician Stars.” When the Roman Catholic Prelate, Piero Dini, questioned how he could be so certain of the connection, Galileo replied in a letter arguing that the discovery of Jupiter’s four moons were inextricably connected with the family’s rising political and economic influence. Galileo also talks about how smaller planets might affect our destiny in ways that we are unaware and distinguishes between superior and inferior causes of planetary influence, writing:

“If therefore, of the inferior causes, those which arouse boldness of heart are diametrically contrary to those which inspire intellectual speculation, it is also most reasonable that the superior causes (if indeed they operate on us) be utterly different from those on which courage and the speculative faculty depend; and if the stars do operate and influence principally by their light, perchance it might be possible with some probable conjecture to deduce courage and boldness of heart from very large and vehement stars, and acuteness and perspicacity of wit from the thinnest and almost invisible lights.”5

It is easy to view Galileo’s interest in astrology as the result of social and historical circumstances. While it is undoubtedly true that astrological practice was common among the scientific elite during the Renaissance period, particularly among the aristocracy of Italian society, his writings suggest a sincere belief in the idea that planets and stars influenced humankind’s destiny. Moreover, there is evidence to indicate that he not only produced astrological readings for the Italian aristocracy but his close family as well, suggesting a personal belief in its predictive powers.

Although Galileo has come to symbolise the power of modern science to enhance our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it, many people forget he was deeply engaged in the mystical practice of astrology and its power to predict the economic, social and political destinies of people’s lives. Although many scientists denounce astrology as pseudoscience, there is no denying that it played an interesting and significant role in the history and development of science, particularly in regards to Galileo’s life.

Paracelsus and the Hermetic Tradition

Paracelsus, or Theophrastus von Hohenheim, was a Swiss-born physician, alchemist and astrologer. Born in 1493, Paracelsus was an influential figure in the ‘medical revolution’ during the German Renaissance and emphasised the importance of experimentation in medical science. He has been labelled the ‘father of toxicology’, one of his most notable phrases being, “The dose makes the poison.”

Paracelsus was also one of the first people to suggest that physicians should receive an education in the natural sciences and study the basic principles of chemistry as part of their schooling. Interestingly, he is credited with giving the element ‘zinc’ its name as well as inventing chemical therapy, chemical urinalysis and early theories of digestion.

While the medical establishment opposed many of his ideas at the time, particularly his views on medical education, he is currently recognised as one of the most influential figures in the history of medicine. His discoveries contributed significantly to the development of natural science and transformed our understanding of chemistry and its application in relation to medicine. Saying this, however, many forget that Paracelsus was immersed in hermetic philosophy and the mysterious world of the occult.6

Paracelsus had a profound interest in astrology, the art of prediction based on the position of stars and planets. Since medicine and astrology were closely connected during Paracelsus’s lifetime, he believed in the commonly held notion that each part of the body corresponds with a specific planet or zodiac sign, and therefore medical procedures should be undertaken according to the position of the solar system to ensure their effectiveness.

He also believed in the hermetic idea there are two worlds: the microcosm (which refers to the world of man and Earth) and the macrocosm (which is the heavenly universe or the spiritual world) and that these two worlds interact and influence each other. He states that:

“Know that there are two kinds of stars – the heavenly and the earthly, the stars of folly and the stars of wisdom. And just as there are two worlds, a Little World [the Microcosm, man] and a Great World [the Macrocosm, the Universe] and just as the little one rules over the great one, so the stars of the microcosm rule over and govern the Stars of heaven.”7

There has been much discussion about the historical sources of Paracelsus’s known magical beliefs. The Archidoxis Magica, for example,was supposedly written by Paracelsus in 1561 and contains information on magical talismans that can be used to cure illness and disease. Many historians dispute that he produced the manuscript since none of his other works discuss the use of talismanic objects; however, it is possible that he may have acquired a sudden interest in their magical potential.

While the authorship of Archidoxis Magica remains subject to scholarly debate, there is no denying that mysticism deeply influenced Paracelsus; in particular the belief that each organ corresponds with a planet and precious metal, which is central to the philosophy of hermeticism. During the medieval period, the Sun was thought to rule over the heart and its corresponding metal was gold. The Moon ruled the brain and its metal was silver. Mercury ruled the lungs and its metal was silver or quicksilver. Venus ruled over the kidneys and its metal was copper. Mars ruled over the bladder and corresponded with Iron. Jupiter governed the liver and corresponded with Tin, and Saturn ruled over the spleen and its metal was lead. Therefore, one can see that Paracelsus believed in the hermetic idea of microcosm and the macrocosm; that the body corresponds with the structure of the cosmos and that both spheres must exist in a state of harmony for man to attain earthly and spiritual perfection.

Saying this, however, Paracelsus was not a determinist astrologer and believed that while the planets and stars could influence human destiny, we still have some degree of free will, writing:

“Even if he is a child of Saturn and if Saturn has overshadowed his birth, he can still escape Saturn’s influence, he can master Saturn and become a child of the Sun.”8

The life of Paracelsus highlights the blurred line between science and mysticism that secretly guided the history of modern science. Although he is credited with scientific innovations such as urinalysis, toxicology and chemical therapy, Paracelsus had a serious interest in the practices of astrology, alchemy and hermeticism. There is much scholarly debate regarding which manuscripts can be attributed to Paracelsus, but the evidence clearly suggests he was not a conventional scientist; he was an inquisitive mind, deeply immersed in the occult.

Conclusion

The distinction between the occult and science has not always been as clear-cut as many of us like to think it is. Many of the influential scientists that we have come to associate with the birth of modern science were clearly involved in the study and practice of alchemy, astrology and biblical prophecy. Moreover, it would appear that many of these scientists believed in the power of these practices while simultaneously recognising the importance of scientific inquiry.

Galileo was a key figure in the transition from natural science to the scientific revolution, however, he also believed that planetary bodies could influence the destiny of humanity. Similarly, Newton used complex mathematical principles to outline his theory of gravity but also turned to biblical prophecy to predict the end of the world. Paracelsus made a number of discoveries in chemical science but also believed in hermeticism.

It is easy for modern science to portray its historical development as linear and coherent, but many of the individuals responsible for humanity’s greatest scientific achievements were inquisitive minds fascinated by the mysterious, peculiar and esoteric world of the occult.

Footnotes

1. John Maynard Keynes (1946), ‘Newton, the Man’ [online] available at phys.columbia.edu/~millis/3003Spring2016/Supplementary/John%20Maynard%20Keynes_%20%22Newton,%20the%20Man%22.pdf

2. Wikipedia (2018), Isaac Newton’s occult studies [online] available at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Newton%27s_occult_studies

3. Ken Ludden (2012), Mystic Apprentice Master Volume with Dictionary, lulu.com, page 413

4. Britannica, Galileo: Italian Philosopher, Astronomer and Mathematician [online] available at www.britannica.com/biography/Galileo-Galilei

5. Nick Kollerstrom (2004), Galileo’s Astrology, skyscript.co.uk [online] (available) www.skyscript.co.uk/galast.html

6. Wikipedia (2018), Paracelsus [online] available at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paracelsus

7. Nicholas Campion (2009), A History of Western Astrology Volume II: The Medieval and Modern Worlds, Bloomsbury, page 117

8. www.renaissanceastrology.com/paracelsus.html

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.