From New Dawn 198 (May-June 2023)

As an example of militant action in favour of the greatest possible degree of open-mindedness, and as an initiation into the cosmic consciousness, the works of Charles Fort have been a direct source of inspiration for the greatest poet and champion of the theory of parallel Universes, H.P. Lovecraft…

– Louis Pauwels & Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians

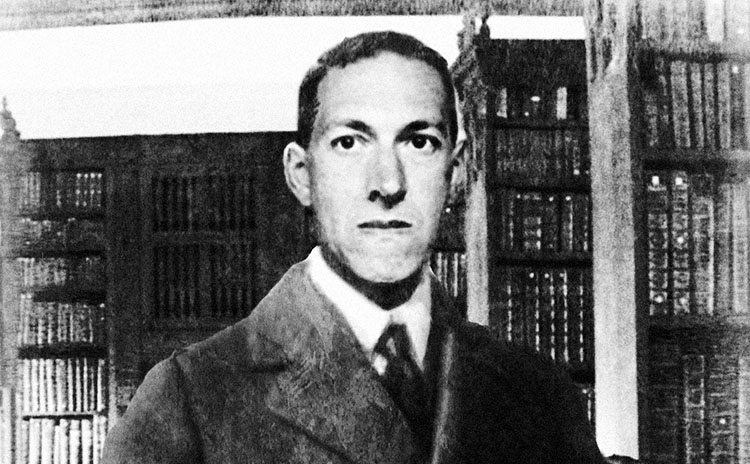

Many people know of Howard Phillips Lovecraft’s (1890–1937) existential and otherworldly horror stories – or at least have seen some adaptation. Lovecraft’s influence across fiction, film, gaming, and beyond is vast and immeasurable, and celebrated artists cite the author as a major creative inspiration, from novelist Stephen King (IT, The Shining), graphic novelist Alan Moore (V For Vendetta, Watchmen), and author Jorge Luis Borges, Japanese writer Chiaki J. Konaka (Serial Experiments Lain, Marebito), manga artist Junji Ito (Uzumaki, Tomie), and directors Guillermo Del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, The Shape of Water) and John Carpenter (The Thing, Halloween, They Live) – the list goes on and on.

Despite his influence, few people know that HP Lovecraft was a prolific political writer who railed against both the soulless greed of American capitalism and the culture-destroying wrecking ball of Soviet communism.

In Lovecraft’s early political writings, published in his amateur journal The Conservative, the primary target of his tirades was bolshevism. This ‘aristocrat of the soul’ feared communism would destroy high art and culture by demolishing the aristocratic (or, in the case of the United States, WASP pseudo-aristocratic) hierarchy.

Lovecraft also criticised the concept of democracy, making similar observations to those that the Italian philosopher and occultist Julius Evola offered more than a decade later in his 1934 book Revolt Against the Modern World.

“There is no such thing – there will never be such a thing – as good and permanent government among the crawling, miserable vermin called human beings,” Lovecraft declared in an October 1921 article titled Nietzscheism and Realism.

“Aristocracy and monarchy are the most efficient in developing the best qualities of mankind as expressed in achievements of taste and intellect; but they lead to unlimited arrogance,” he continued. “That arrogance in turn leads inevitably to their decline and overthrow. On the other hand, democracy and ochlocracy [‘mob rule’] lead just as certainly to decline and collapse through their lack of any stimulus to individual achievement. They may perhaps last longer, but that is because they are closer to the primal animal or savage state from which civilised man is supposed to have partly evolved.”

In the same article, Lovecraft called for a Roman-style aristocracy that would accept any man who could prove himself “aesthetically and intellectually fitted for membership,” before channelling Schopenhauer and the future works of nihilist philosopher Emil Cioran with the line: “Universal suicide is the most logical thing in the world – we rejected it only because of our primitive cowardice and childish fear of the dark. If we were sensible we would seek death – the same blissful blank which we enjoyed before we existed.”

Later, as the Great Depression crippled Americans and Lovecraft became increasingly ill and destitute, he altered his worldview – ridiculing the out-of-touch laissez-faire mentality of politicians and industrialists and warning that some form of American socialism would be necessary to prevent the rise of communism in the US.

In a 1933 piece, Lovecraft criticised the “artificial finance-and-business tradition” which had become dominant in the US and argued that the capitalist class was willing to do anything – including kill off the masses through war – to “save the sacred cultural principles of ‘sound business’, ‘rugged individualism’, and bigger profits for people who do not need them.”

“It is by this time virtually clear to everyone save self-blinded capitalists and politicians that the old relation of the individual to the needs of the community has utterly broken down under the impact of intensively productive machinery,” Lovecraft observed before warning that America would have to make radical changes – including guaranteed work for every American and the limitation of private property – to deter a revolution he claimed would start with good intentions, but ultimately result in “ruthless destruction of cultural values which such an upheaval would bring.”

In another article, dated November 1933, Lovecraft complained that industrial laissez-faire capitalism had led only to America’s resources becoming concentrated in the hands of an increasingly small few.

On the “pompous financiers” and politicians who had caused such a state of affairs, Lovecraft said that the “Americanism” and “freedom” they spoke of no longer meant anything more than “certain technical business principles” which “enable 2% of the population to corral 80% of the national resources and condemn an ever-increasing minority to unemployment and starvation.”1

He lambasted the “capitalistic class” for regarding “the now-passing economic order” – as the Great Depression ended – to be “a good one.”

Lovecraft attacked: “All our smug ‘solid men’ and ‘best citizens’ have habitually condemned thousands to slow starvation and hundreds to actual death through industrial policies designed to give a few luxurious stockholders the added profits enabling them to keep three motor cars instead of two.”

Many of Lovecraft’s observations and criticisms are eerily relevant today, nearly a hundred years on. With the ongoing decline of the US empire, the same out-of-touch cliches and policies that Lovecraft cited as responsible for the destruction of the American community back in his day still repeat today.

Politicians on both the left and right use the same calls for “freedom” and “Americanism” as they did in the early 20th century, only this time to justify expensive, far-away wars while ordinary Americans suffer the effects of inflation and plummeting quality of life.

Although Lovecraft started out politically conservative and later advocated some socialist positions in response to the devastation wrought by the Great Depression, for the most part, he remained a social conservative and continuously supported the concepts of aristocracy and hierarchy throughout his life.

Lovecraft believed that the “old aristocracy” – which still held sway in 1930s America – would ultimately support the necessary changes to avoid communism due to their indifference to the “moneyed bourgeois element” with the most to lose. Ironically, he cited the British fascist leader Oswald Mosley and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt as two examples of aristocrats “who actively lead the quest for a workable social order.”

Lovecraft laid out his vision for men like Mosley and Roosevelt:

Indeed, the salvation of society really depends on the faithful and diligent services of disinterested gentlemen – since the inflamed masses without leaders can only tear down without building up. The people as a whole are densely and hopelessly ignorant – mere blind forces either cowed to silent suffering or bursting into resistless fury under too much goading – hence democracy is and always has been and will be a joke… or a tragedy. Salvation rests wholly with the trained man of vision and cultivation without the profit motive – namely, the fascistic leader.

At the time of Lovecraft’s article, Mosley had recently launched the British Union of Fascists and – despite his aristocratic connections – was interned in 1940 in a British concentration camp for more than three years due to his beliefs. Roosevelt led America into World War 2 before passing away just months before the detonation of two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Ultimately, Lovecraft never saw the war or the era of prosperity that the US would experience in the decades following. He would never see the fall of fascism or the fall of the Soviet Union, and he would never see American capitalism reach new levels of horror. Even his own creative mind would have struggled to foresee it. He would never see his work – widely ignored and maligned during his lifetime – become some of the most popular stories in horror and science fiction history.

Lovecraft died in his native Providence, Rhode Island, from intestinal cancer on 15 March 1937, age 46. He left this world in poverty and in severe pain.

While Lovecraft died more than 86 years ago, his work and the intricate world he created continue to inspire and fascinate new generations. Despite the fact that the bulk of Lovecraft’s legacy can be seen in the cinema, comic books, video games, and other entertainment, it also appears in more serious fields such as the occult and even the military.

In a September 2022 article for 19FortyFive titled “Read H. P. Lovecraft To Understand War,” James Holmes – chairman of Maritime Strategy at the US Naval War College and a former US Navy officer – argued that reading Lovecraft and other weird fiction “primes military practitioners and analysts to notice weird or eerie anomalies in the profession of arms.”2

“Detecting a phenomenon is the first step toward adapting to it or turning it to advantage,” he wrote, adding that Lovecraft’s stories could help military strategists “make sense of the past, survey the world around us, and potentially glimpse the future.”

Could that same argument be made for the study of conspiracies, cover-ups, and Fortean activity? Could this also be why Lovecraft’s ideas are so ingrained in much of the modern occult?

Charles Fort and his investigations into the paranormal influenced Lovecraft, who was also obsessed with the unknown, the unexplained, and the concept of forbidden knowledge. Lovecraft referenced “the extravagant books of Charles Fort with their claims that voyagers from other worlds and outer space have often visited the earth” in his 1931 science-fiction horror story The Whisperer in Darkness.

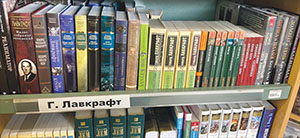

In his article, Holmes cites examples of how Lovecraft’s work could help NATO and Ukraine in their conflict against Russia – an interesting observation since Russia is among the countries where Lovecraft’s tales are most widely read.

Russian translations of Lovecraft can be found in abundance in Moscow bookstores, with some outlets holding dedicated shelves to his weird fiction – a rare sight in even English-speaking countries. Remarkably, Russian President Vladimir Putin himself addressed the topic of Cthulhu, the fictional cosmic entity that appears in several of Lovecraft’s stories, after questions about the apocalyptic awakening of the sleeping, underwater tentacle god were the fourth most popular at a Q&A in 2006!

While some critics of the Russian president have accused him of holding a “dark pact” with Cthulhu, Putin told Lovecraft-mad Russian youth: “I am generally suspicious of any otherworldly forces. If someone wants to turn to true values, then it is better to read the Bible or the Koran. It will be more useful.”3

Footnotes

1. hplovecraft.hu/index.php?page=library_etexts&id=771&lang=angol

2. 19fortyfive.com/2022/09/read-h-p-lovecraft-to-understand-war/

3. majikthise.typepad.com/majikthise_/2006/07/vladimir_putin_.html

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.