From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 15 No 3 (June 2021)

In 2014, at the annual meeting of United Russia, the Russian Federation’s dominant political party, amidst the standard rhetoric of party politics, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave his regional governors a list of books he said they should read.

Putin likes to come across as a reader – Dostoyevsky is a favourite writer of his – and he isn’t averse to name dropping some classics in the middle of an interview. But the list he gave to his governors at that meeting didn’t include Crime and Punishment, War and Peace, or Dead Souls, to mention just a few of the contributions to world literature that Mother Russia has made, by way of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Gogol.

The names that drew attention from political commentators in the West wouldn’t be easy to find on Kindle or in an airport bookstall on your way to Vladivostok, Irkutsk, or wherever your regional office might be. They were names of philosophers, individuals who, traditionally, are not known for producing page-turners.

Putin wanted his governors to become familiar with them because the Russia he saw on the horizon would be informed with the spirit of their thought.

A lot has happened since that meeting in both Russia and the world. Among other things, the United States had some new presidents. Putin, of course, has remained in power, seemingly as fixed in place as the tsars of old.

No doubt Joe Biden has advisers guiding him on how best to establish a new relationship with Russia. But if he finds himself with time to kill en route to wherever his proposed summit with the Russian leader might be, he might up his game a bit by skimming through the weighty volumes that Putin assigned to his governors.

The three thinkers that Putin suggested the governors should read were Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), a friend of Dostoyevsky and, according to the late American Russian scholar James Scanlan, the greatest and most influential of Russian philosophers; Nikolai Berdyaev (1874–1948), an aristocratic, fiercely independent thinker who combined a passionate religious temperament with an existential commitment to freedom; and Ivan Ilyin (1883–1954), a much more political thinker than Solovyov and Berdyaev.

All three were part of a remarkable period in Russia’s cultural history known as the Silver Age, a time of deep spiritual and mystical experiment and excitement aborted by the rise of the Bolsheviks.

In recent years, Putin has looked back to this time in an attempt to revive the character of “Holy Russia” as a way of resolving the identity crisis Russia has struggled with since the collapse of the Soviet Union. For some critics in the West, the philosophers Putin namechecked were simply examples of a kind of “mystical exceptionalism,” a reheating of nineteenth-century ideas about Russia’s “messianic role in world history.”1

Whatever Putin’s real aims in namedropping these thinkers may be – and of course he is a cagey politician before anything else and has his own purposes in mind – they deserve to be read. If nothing else, if Biden did read them, he might get an angle on Tsar Vladimir that might otherwise escape him.

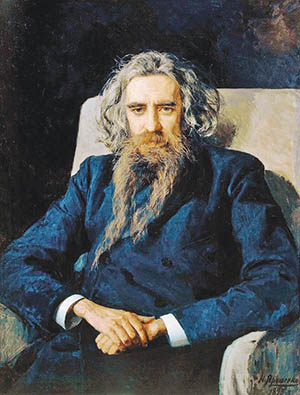

Vladimir Solovyov

Solovyov’s The Justification of the Good, for example, which is on Putin’s list, is a long, detailed, eminently logical and rigorously rational argument for the supreme value of the “good in-itself,” the Good in a Platonic sense, that is.

Since the eighteenth century, the West has seen the “good” in a purely utilitarian sense, a “practical” good, one that can be seen and measured in material things: a new car, a new computer, a holiday in the tropics. Or it sees the good in terms of the consequences of some action. Hence the notions of “the greatest good for the greatest number” and “the ends justify the means,” formulas that historically have had disastrous results.

This idea of a measurable good is at the root of Western consumerism, as well as that of the various socialist alternatives to it; both see the good in terms of higher living standards, more and better things.

While it is undeniably good that all should be fed, clothed, and housed decently – a belief Solovyov, who gave away what money he had, put into practice – a society that defines the good in this way forgets the truth of the Gospel: that man does not live by bread alone.

Solovyov saw that the dominance of rationalism in the West had eclipsed the perception of the spiritual dimension of life, an argument he made in his first major work, The Crisis of Western Philosophy. The series of lectures he gave on the “God-Man,” the path of theosis, our evolution into a higher, more spiritual consciousness, were attended by Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and influenced both. Russia, he believed, could be the birthplace of such a consciousness, and his ideas informed the Silver Age. He died in 1900.

Nikolai Berdyaev

Nikolai Berdyaev was one of the many Russian thinkers, poets, critics and other members of the intelligentsia who in 1922 were aboard the “philosophy steamers” that carried them out of their homeland and into exile in the West, courtesy of Comrade Lenin.

A devout if eccentric Christian, Berdyaev started out as a Marxist but after reading Solovyov rejected Marx’s materialism. He became a radical religious existentialist, obsessed we can say with the idea of freedom. His early work, The Philosophy of Inequality, another on Putin’s reading list, was a response to the enforced egalitarianism of the Revolution.

He argued that the intelligentsia’s passion for the “people” and the “proletariat” had become little more than idolatry. Truth in itself, like Solovyov’s good in itself, had fallen away, and only those truths that were helpful to the Revolution were embraced. (Is there a parallel with our own times, perhaps?) But without real truth, existential truth, human beings fall prey to the forces of materialism and become little more than the property of the state or the market.

Berdyaev continued his philosophical struggle for freedom from Berlin and then Paris, writing book after book, with titles like The Destiny of Man, Slavery and Freedom, and Spirit and Reality, his remarkable autobiography, until his death in 1948.

Ivan Ilyin

Ivan Ilyin started out as a political idealist, believing that if people could grasp what he called “legal consciousness,” a kind of intuition of the need of rule of law, government would not be necessary, as we could govern ourselves. This naivety received a buffeting with the 1905 Revolution, and Ilyin’s views changed radically.

From a kind of spiritual anarchist, he became the advocate of the need for a small group of dedicated men who had achieved “legal consciousness” to guide the vast majority who hadn’t. This was rather the same view as Lenin, except that his small band of dedicated revolutionaries would usher in the new, classless, godless society.

Ilyin’s view was much more that of Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov, who argues that men do not want freedom but bread and that the church, which rules the state, must shoulder the burden of their freedom for them. Like Berdyaev, Ilyin was shipped out of Russia on the “philosophy steamers,” and until his death in 1954, he was a voice of opposition to the Soviets.

Our Tasks is a collection of Ilyin’s writings that Putin put on his list. One essay, “What the Dismemberment of Russia Means for the World,” written in the 1950s, spells out in eerily prescient detail what will happen to Russia with the collapse of communism and the introduction of Western democracy and the free market. In the chaos that would follow what he called “the Balkanization of Russia” – and which actually did happen – Ilyin predicted that a strong man would arise, who would re-establish order and control and reunite the nation… No wonder that of the three, Ilyin’s name turns up the most in Putin’s speeches.

Of course, here I can only suggest why readers might want to take a look at Putin’s philosophers. They all warrant attention; Solovyov and Berdyaev for their own sake; Ilyin, I would say, to get an idea of what’s on the Russian President’s mind.

For more on this subject, read Gary Lachman’s book The Return of Holy Russia, which covers Vladimir Putin, the Silver Age, Solovyov, Berdyaev, Ilyin and the other remarkable figures making up Russia’s tumultuous spiritual history.

Footnote

1. www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/opinion/brooks-putin-cant-stop.html

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.