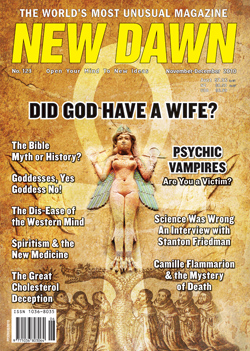

From New Dawn 123 (Nov-Dec 2010)

Every civilisation needs a myth; but woe to the civilisation whose myth has been found wanting. That is the position of Christianity today. It came to ascendance at a time when the myths of Greece and Rome had lost their credibility. The pagans themselves laughed at the stories of their gods; Plato sought to censor them. Christianity triumphed because it offered its sacred scriptures not as myth but as fact. Mystical adepts had always known that the stories in the Bible were not meant to be taken entirely at face, but as the religion degenerated into priestcraft, these insights were forgotten or suppressed.

Today we have come full circle. Over the last two centuries a staggering number of scholars – the vast majority Christians themselves, many of them clergymen – have laboured on the great project of seeing how much of the Bible is historically valid. The verdict has not, in general, gone in the Bible’s favour. Little by little its validity as a plausible source for the facts it claims to recount has been eroded. In the nineteenth century, scientists such as Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin showed that the epochal changes in geology and biology could not have happened in the six thousand years allotted to them by Genesis, while the German scholar David Friedrich Strauss (who was a Lutheran pastor) showed that much that the Gospels said about Jesus was probably not accurate in any factual sense, but consisted of stories and legends that had accumulated around him after his life.

But the inquiry did not end there. Much of the Hebrew Bible consists of history – the history of Israel from primeval times to around 500 BCE. It tells of patriarchs such as Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; of the bondage of the Israelites and their miraculous liberation by the hand of God; and of David and Solomon and their successors to the thrones of Israel and Judah.

Until fairly recently scholars took much of this account at face value. But as our knowledge of the first millennium BCE in the Near East has improved, it has become more and more obvious that the Bible cannot be entirely trusted even in these areas.

I must digress here to make an important point. Many of the articles in New Dawn present what is called “alternative history” – views of the past that run counter to what conventional scholars believe. This approach is valuable and refreshing, if only because academics tend to operate like a team of horses with blinders on. Nevertheless, what I am going to be saying in this article (and in the following article, “God’s Forgotten Wife”) is not alternative history. It is conventional scholarship, and it consists of things that anyone would learn at a mainstream seminary or divinity school, although these findings have not always trickled down to the public at large.

To take one fairly simple example, two hundred years ago nearly everyone in the Judeo-Christian world believed that the first five books of the Bible (known to the Jews as the Torah, to the Christians as the Pentateuch) were written by Moses. Today practically no scholar who is not a fundamentalist believes this. Many scholars do not even believe that a person such as Moses ever lived, or that an exodus from Egypt ever occurred in anything like the way it is described. Moreover, a generation ago it was generally accepted that the accounts of David and Solomon in the books of Samuel and Kings were reasonably accurate – even contemporary – accounts. But today it is agreed that these histories were written centuries later, and the glories ascribed to these two monarchs were vastly overstated.

To summarise all these findings, an article of this length cannot hope to be complete. All the same, it is possible to sketch out some of the major findings along with their implications.

Israel in History: The Archaeological Evidence

The history of Israel begins with the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. The general setting for their lives is best placed in the early second millennium BCE. The original texts (there were several) that make up what today we call Genesis were not written until around the seventh century BCE. Consequently, what we have about these patriarchs is a collection of legends with an interval of a millennium between the events and the written accounts. It would be hard to find anything here that could be called real history.

As we come closer to the present, the picture becomes clearer, although it does not necessarily validate the Bible as a source. The descent of Jacob and his twelve sons into Egypt to escape a famine in Canaan does resonate with a well-documented period (in the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries BCE) in which Egypt was ruled by the Hyksos, Semitic “foreign kings” that came from the northeast. But here too it is very hard to reconcile the biblical account (again written almost a thousand years later) with the Egyptian documents. They portray the Hyksos not as slaves but as rulers; indeed an Egyptian king list includes one “Yaqub” – identical to “Jacob.”1 They did not flee a tyrannical Pharaoh but were thrown out by the Egyptians themselves – an almost complete reversal of the biblical account.

As for the flight of the Israel to the land of Canaan to escape their Egyptian taskmasters, this too is hard to accept, because in the period in which this is supposed to have happened – the thirteenth century BCE – Canaan was an Egyptian province, complete with governors and forts and garrisons. Egypt would retain control over Canaan until around 1160 BCE.

In fact the first mention of Israel in any contemporary text comes from a stele from the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah, the son of Rameses II (often portrayed as the pharaoh of the Exodus), and it dates to 1207 BCE. It tells of an Egyptian campaign into Canaan, and in it Merneptah boasts, “Israel is laid waste; his seed is not.”2 Obviously this is an exaggeration, but it suggests that at this time the people of Israel were an already well-established population at a time when Pharaoh still ruled the land.

Scholars generally agree that there was no conquest of Canaan by the Israelites as described in the book of Joshua. How, then, did Israel come to be? To understand this, we have to grasp something about the geography of Palestine. The country can be roughly divided into three north-south strips. The first is a fertile coastal plain parallel to the Mediterranean shore. The second is a band of hill country east of the plain. The third and easternmost is the Jordan River valley. It was the second of these regions, the hill country, that was the Israelite homeland. In the Late Bronze Age (1500-1200 BCE), it was sparsely populated. But at the beginning of the Iron Age in the thirteenth century, its population rose dramatically. And it is these Iron Age settlements that scholars believe were the homes of the proto-Israelites. There was very little in their material culture (alphabet, pottery, and so on) that differentiated them from the Canaanites of the coastal plain, except that the proto-Israelites’ culture was more primitive – the pottery was crude and poorly ornamented, for example – and, strangely, the bones of pigs are almost completely absent from the animal remains that are found at these sites, indicating that these people, whoever they were, had a taboo against eating pork even in the earliest times.

Where did these hill people come from? Scholars do not agree entirely, but they are more or less unanimous in stating that most of them were not freed slaves coming up from Egypt. In all likelihood, they were people fleeing the social breakdown in the Bronze Age culture of the Palestinian coastal plain – itself only a localised version of the end of Bronze Age civilisation that was taking place all around the eastern Mediterranean. They were probably augmented by a small number of nomads who adopted sedentary ways of life. These hill people were not city dwellers; their social units were extended families that were themselves organised into tribes, which in turn formed a loose confederation that resembles the one described in the book of Judges.

Myth Made History: Moses, David & Solomon

Did Moses live? There is no reference to him in any contemporary source. The name Moses is a curious one; it is Egyptian, and it literally means “son,” as we see in some Egyptian names: Thutmosis (or Thutmose), the name of several pharaohs, means “son of Thoth,” the god of learning. It would be odd if Moses had been the prophet’s original name, just as in the English-speaking world there are many Johnsons and Williamsons, but practically nobody with the surname “Son.” Possibly his name originally included the name of an Egyptian god that Moses himself – or later chroniclers – chose to remove.

Scholars thus have stopped believing in any great migration that resembles the biblical account. To the extent that they lend any credence to the story of Exodus at all, they grant the possibility that a charismatic leader led a small band of former Semitic slaves to the hill country of Palestine and that as Egyptian power began to wane in that area, this people, along with the hill people that had already settled there, was able to shake off its chains.

To move on to the late eleventh and tenth centuries BCE, the period that biblical historians call “the united monarchy,” when Israel was supposedly ruled by a single king – Saul, followed by David and David’s son Solomon. According to the Bible, this was the zenith of Israel’s power and influence. David supposedly ruled over a territory that stretched from the Euphrates to Gaza (1 Kings 4:24), while Solomon accumulated vast riches and a thousand wives. But the archaeological remains and extrabiblical texts say virtually nothing about these rulers; some scholars go so far as to doubt whether there ever was a united monarchy at all. Richard A. Freund, professor of Jewish history at the University of Hartford, Connecticut, in the US, sums up the situation:

If… David was so prominently involved in the lives of so many different peoples in the region, it stands to reason that he would be mentioned in one of these different non-Israelite literatures. If… Solomon conducted international relations with Egypt, marrying into the royal family and importing horses, why wouldn’t there be a record somewhere in Egypt that would corroborate this relationship?…. But no independent corroboration of these events exists from archaeological evidence or source not influenced by biblical tradition, save perhaps an early medieval collection called the Kebra Nagast, the national epic of Ethiopia.3

The earliest extrabiblical reference to David comes from an inscription found at Tel Dan in northern Galilee in 1993. Dated to the ninth century BCE, it contains a claim by Hazael, king of Aram, that he has killed Ahaziah, king of Israel, and Jehoram, “king of the house of David.”4 Hazael, Ahaziah, and Jehoram are all mentioned in the Bible, so this inscription confirms these men lived and ruled and that there was a house of David in the ninth century BCE. Nevertheless, this inscription dates more than a hundred years later than David is supposed to have lived, so it confirms nothing more about him.

Nor is there much archaeological evidence for the existence of Solomon’s Temple, which would have been built around 940 BCE.5 Indeed the archaeologist Israel Finkelstein contends that Jerusalem, supposedly Solomon’s magnificent capital, was actually a rather humble place. “Digging in Jerusalem has failed to produce evidence that it was a great city in David or Solomon’s time,” he argues. “Tenth century Jerusalem was rather limited in extent, perhaps not more than a typical hill village.”6

There is archaeological evidence for a highly prosperous and centralised monarchy in Israel, but, Finkelstein contends, it was in the ninth century BCE and not the tenth. Remains include palaces, storage centres, and even stables. They are centred around Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel (the ten tribes that seceded from the house of David after Solomon’s death, ending the united monarchy). They were the work of the Israelite king Omri and his heirs – every last one of whom, according to the Bible, “wrought evil in the eyes of the Lord” (1 Kings 16:25).7 The most notorious of the Omrid dynasty was Ahab, whose queen was the proverbially wicked Jezebel.8

It is thus really only in the ninth century BCE that biblical history and the extrabiblical evidence begin to converge, and in the eighth century the picture becomes still clearer. The Bible tells of the destruction of the northern kingdom of Israel at the hands of the king of Assyria in 722 BCE (2 Kings 17:3-23); this is confirmed by an Assyrian stele. The Bible also says that Hezekiah, king of the southern kingdom of Judah, was able to save his tiny nation from destruction by the Assyrians. This too has a parallel in the surviving Assyrian records – although these happen to mention the huge tribute of gold and silver that Hezekiah had to pay in return. The Bible, by contrast, credits the survival of Judah to the miraculous intervention of Yahweh, whose angel “smote in the camp of the Assyrians an hundred fourscore and five thousand” (2 Kings 19:35-36).

Yahweh’s Companions?

But it is when we turn to the religious history of ancient Israel that the picture becomes truly astonishing. After all, the intense interest in the Bible has a great deal to do with the part that is said to be played by God in history: specifically the revelation of the one true God, Yahweh, to the nation of Israel, and his granting of the land of Canaan to them in perpetuity on condition that they obey his law and worship him alone. But here, too, the extrabiblical sources create a much more checkered picture. Egyptian texts of the Late Bronze Age do show some familiarity with a god called “Yhw” (Egyptian, like Hebrew, did not employ vowels in its script) in connection with some nomads located in the southern part of Jordan.9 This resonates with the biblical account, which has Moses learning about Yahweh in Midian (see Exodus 3), which is in the same area. And it is possible, as we have seen, that a charismatic leader like Moses could have led a small band to Canaan and used this god as a rallying-cry to unify the hill folk and create a national identity for them. But even so, the reality would be very different from the story narrated in the Pentateuch.

Scholars today generally agree that the revelation of a monotheistic Yahweh to Moses and his spiritual heirs is not an accurate picture of what happened. Instead, they contend, Yahweh only gradually – over the course of several centuries – came to be seen as the sole god of Israel and as the supreme god of the universe. Frank Moore Cross, one of the most distinguished Old Testament scholars of his generation, has argued that originally Yahweh was an epithet of El, the high god of the Canaanite pantheon, in his function as patron deity of a confederation of tribes known as the Midianite League. Cross says that Yahweh later became differentiated from El among the proto-Israelites, and eventually came to displace him.10

Margaret Barker, another biblical scholar, has an even more radical suggestion. She contends that throughout most of the era of the First Temple (c.940-586 BCE), both El and Yahweh were worshipped in the Temple in Jerusalem as separate deities, forming a trinity with Asherah, Yahweh’s divine consort (see the next article). El retained his position as the high god – the lord of the universe – whereas Yahweh was the national god of Israel alone. It was only with the “reforms” of the religion of Judah that took place under King Josiah in 621 BCE (2 Kings 23) that Asherah was discarded and Yahweh was conflated with El. In fact, Barker claims, the Josianic “reform” was actually a radical restructuring of the faith. The Bible portrays it differently, as a purge of alien elements, but that is because the Bible was written by the party that instigated the purge. It was this party that created the Deuteronomic history in the Bible (comprising Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings), which has shaped our historical understanding of this period to this day. Nearly all the biblical texts I have mentioned above are taken from the Deuteronomic account.

Obviously there is a great deal more to say about these matters, and endless numbers of books have been written about them. I have limited my discussion here to the Hebrew Bible simply because of space. The New Testament is problematic as well, but for different reasons. Here it is not archaeology or the larger historical context that is the question: there is ample extrabiblical evidence for the existence of the Second Temple, which was still being completed at the time of Christ and was sacked by the Romans in 70 CE. Indeed the Temple’s western wall, today called the Wailing Wall, still survives. There is also ample extrabiblical documentation of figures such as Herod the Great and Pontius Pilate. There is no such documentation for Jesus, but this is not in itself problematic. We might reasonably expect some archaeological evidence for the existence of David and Solomon, who were supposedly great monarchs, but Jesus was comparatively obscure in his own day. It is only when we ask who Jesus was and what his earliest followers thought him to be that the controversies arise.

In any event, we have seen a strange reversal over the last two hundred years. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the educated world in the West took the Bible as history while the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, were written off as legend. Then in the early 1870s, the pioneering archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann unearthed the ruins of Troy in Asia Minor, and scholars realised that the Homeric poems – whether or not their specific characters ever lived – were firmly grounded in the world of Late Bronze Age Greece. Ironically, when scholars examined the Bible in the same fashion, they came up with little more than a few isolated inscriptions and the stables of the wicked King Ahab.

Literal Truth of the Bible Under Attack

Does this all matter? Does the Bible have to be true in a historical sense? Not necessarily. As I noted at the outset, esotericists have long acknowledged that these stories are in many ways symbolic of higher truths. The book of Exodus, with its ten plagues and miraculously gushing stones, is in all likelihood not true historically. But the British Kabbalist Warren Kenton, writing under the pen name Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi, gives an intricate and profound analysis of the mystical dimensions of this saga in his book Kabbalah and Exodus.

What the original authors of the biblical texts may have intended is a difficult question to answer, since we do not even really know who they were. Nevertheless, Christianity has often proselytised on the premise that the stories in the Bible are literally true. It is reasonable to assess the Bible in terms of the claims that its proponents have made for it, and those claims have been found wanting.

All this said, the scholars who have delved so deeply into the historicity of the Bible over the last two hundred years have shown tremendous moral and intellectual courage. They have not, for the most part, been debunkers but have been serious scholars of Judaism and Christianity who are often profoundly committed to their faith. Some have turned to archaeology to validate this faith and have had to admit they were wrong. Joseph Callaway, an American professor of biblical archaeology, tried to find the city of Ai, supposedly destroyed by Joshua (Joshua 7-8), but he concluded that the city did not exist in Joshua’s time. He wrote: “For many years, the primary source for the understanding of the settlement of the first Israelites was the Hebrew Bible, but every reconstruction based on the biblical traditions has floundered on the evidence from the archaeological remains.”11 Callaway took early retirement from his very conservative seminary rather than cause any embarrassment on this count.

Many journalists have lacked Callaway’s integrity, so you can pick up an American newsmagazine such as Time and read an account of Moses that treats him as if he were Churchill or John F. Kennedy.12 To bring the far more elusive truth to light would no doubt cause many readers to cancel their subscriptions. Sometimes the weaker a myth is, the more stridently it is defended.

Sources:

Margaret Barker, The Great Angel: A Study of Israel’s Second God, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992.

Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of Religion of Israel, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1973.

William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the History of Ancient Israel, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2001.

– – . Who Were the Ancient Israelites and Where Did They Come From?, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2003.

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Richard A. Freund, Digging through the Bible: Modern Archaeology and the Ancient Bible, Plymouth, U.K.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

Simon Goldhill, The Temple of Jerusalem, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi, Kabbalah and Exodus, London: Rider, 1980.

Hershel Shanks, et al., The Rise of Ancient Israel, Washington: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1992.

D. Winton Thomas, ed., Archaeology and Old Testament Study, Oxford: Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1967.

Footnotes:

1. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites?, 10.

2. Finkelstein and Silberman, 57; see also Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites?, 202.

3. Freund, 117.

4. Freund, 117–18.

5. Goldhill, 31.

6. Finkelstein and Silberman, 124, 133.

7. Biblical quotations are taken from the Authorised (King James) Version.

8. For an account of the archaeological findings and their relation to the house of Omri, see Finkelstein and Silberman, ch. 7.

9. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites?, 128.

10. Cross, 44, 71.

11. Quoted in Dever, 47–48.

12. A good example is Emily Mitchell and David Van Biema, “In Search of Moses,” Time, Dec. 14, 1998; www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989815-7,00.html; accessed Sept. 21, 2010. The article is worth careful deconstruction. It does, for example, ask “Did Moses even exist?” and mentions such evidence as the Merneptah inscription. But the vast bulk of it is devoted to a retelling, in Time-style prose, of the biblical account as literally true. The reader is subtly led to believe that somehow, in the end, all these things did happen. The article is a cover story, timed to the release of the film The Prince of Egypt. A more recent article, “How Moses Shaped America,” by Bruce Feiler (Time, Oct. 12, 2009; www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1927303-3,00.html; accessed Sept. 21, 2010) discusses the political uses made of the Moses story by American politicians without attempting to touch the historical issue of whether this figure actually lived.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.