From New Dawn 142 (Jan-Feb 2014)

When the veil descended, men revered what it covered. And as time went on it seemed to hide more and more and was revered still more. Then, when it was heavy with age, young men fresh and arrogant demanded the removal of the veil and demanded to see what was hidden. For they said that whatever is hidden from the people cannot be for the common good. In the thunder and lightning of indignation, the veil was torn down. Nothing lay beyond. At first the young men were startled, but then they laughed jubilantly at the absurd fraud they thought they had uncovered. And the old men grieved, cursing the young men because they had destroyed the veil.

– The Tree of Life Oracle

Why do so many creation sagas sound alike? Why can myths of a universal flood be found worldwide? And why do we find prophecies of an end of the world in equally far-flung places?

There are two basic theories that try to account for these similarities. One is the archetypal, which argues that these universal myths point to a common structure within the human mind. The Swiss psychologist C.G. Jung is the best-known advocate of this approach. The other is the diffusionist view, which claims that these resemblances point to a common source of myth in the past.

In a recent book, entitled Origins of the World’s Mythologies, E.J. Michael Witzel, a professor of Sanskrit at Harvard University, argues on behalf of the diffusionist view. He compares the myths of nations around the world and paints a picture of the history of myth that reaches back as far as 100,000 years.

Witzel claims that certain universal mythic elements may actually go back to the earliest stages of humanity, when the whole species still lived in Africa. He calls this strain the “Pan-Gaean” mythos (he uses the geological names of prehistoric continents to label these different strata). The next oldest is that of “Gondwana,” a mythos that can be found today chiefly among the indigenous peoples of sub-Saharan Africa and Australia. By this account, the gods, heaven, earth, and so on, preexist; there is no story that tells of their origins. The gods create humans from substances such as trees or clay, but the humans commit acts of hubris and are punished by a worldwide flood (an element that apparently goes back to the Pan-Gaean mythos). Afterward, local tribes emerge.

The myths of the rest of the world – not only Europe and Asia but the Americas and even Polynesia – are “Laurasian.” They first arose, probably in southwestern Asia, between 40,000 and 20,000 BCE, and share one crucial feature: unlike the earlier strains, they all present a continuous and more or less similar narrative; Witzel even describes it as a “novel.” It has some of the features of the earlier Gondwanan story, but it goes much further and is much more coherent. It begins with the origins of the cosmos and the gods and extends to the birth of humanity, whose history is delineated into four or five “ages.” Humans show hubris in this narrative as well, and are also punished with a universal flood.

The mythos proceeds to the end of time, in which heaven and earth are destroyed and a new heaven and new earth emerge. This event is represented in legends as different as the Nordic Götterdämerung (“twilight of the gods”) and the Last Judgment of Christianity. Indeed, for Witzel, the creation narratives and eschatology of the Bible are only the latest manifestations of the Laurasian mythos.

Why have these myths lasted so long? According to Witzel, one reason is that, quite simply, they are good stories. Another is that the Laurasian mythos in particular recapitulates the human lifespan on a universal scale: like us, it is saying, the cosmos is born, grows to maturity, and eventually withers and dies; it even goes through several distinct stages of development. He also echoes the claim made by certain neuroscientists that in some yet undefined way the human brain is “hardwired” for myth and religion (although this leads toward the archetypal view that Witzel dismisses).

We can also see that these myths have been recast into new forms every few thousand years. Little by little, the old gods cease to be taken seriously; sometimes they are mocked. This happened in classical antiquity. The period that is most familiar to us – from 500 BCE to 300 CE – is a comparatively late one for that civilisation, and we can see the old gods losing their hold. Around 500 BCE, the pre-Socratic philosophers arose in Greece, some of whom disdained the gods, claiming that they were mere personifications of natural phenomena or outright fictions. The gods were also satirised in literature then and in later centuries, as we see in the comedies of Aristophanes and the dialogues of Lucian. While paganism remained alive in the popular mind until Christianity won out in the fourth century CE, the intelligentsia had long ceased taking it seriously – or interpreted the gods symbolically or allegorically. (Sometimes when the new mythos takes over, it keeps some of the gods of the previous one, but as demigods or demons: early Christianity saw the Greek and Roman gods this way.)

The Ages of Greece

Every people have gods to suit their circumstances.

– Henry David Thoreau

This constant need for creation and recreation of myth leads us to wonder what may cause these upheavals. It is tempting to look at this issue in the light of the “ages” that are so universal a mythic motif. Among the most familiar are those of the Works and Days by Hesiod, a Greek poet of the eighth century BCE: the ages of Gold, Silver, Bronze, the Heroes, and Iron. Hesiod’s sequence of these periods, like those of many Laurasian myths, is one of decay and degeneration, from the Golden Age, whose people “lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief” down to the present Age of Iron, when “men never rest from labour and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night.” Although Hesiod laments that he had rather “died before or been born afterward,” the present age will deteriorate still further, and will approach an end when people “come to have grey hair on their temples at their birth.”

Hesiod may be preserving some historical memory here, at least in his choice of names. The Bronze Age in Greece lasted till around 1100 BCE, and the Age of Heroes centres around the sack of Troy, which is generally dated to the early twelfth century. The Greek Dark Ages (1100-750 BCE), when iron was introduced, then began, at the end of which Hesiod himself lived. The ages of Gold and Silver would then be part of a more or less imaginary mythic prehistory.

While the idea of the Golden Age still floats about in the popular mind today, Hesiod’s other ages do not. But we have something similar in the mythos of Christianity. One common version of Christian sacred history speaks of several “dispensations” or different periods of worship. Based on the biblical narrative, they are usually divided thus: the period between Adam and Noah; the period between Noah and Abraham; the period between Abraham and Moses; the one between Moses and Christ; and from Christ to the present, which will last until Judgment Day, and restore a new heaven and a new earth. The last days, again, will be characterised by decay and degeneracy, as we see in Christ’s apocalyptic discourse in Matthew 24, Mark 13, and Luke 21.

Thus we see ancient Laurasian myth transposed into both classical Greek and Christian modes. And this in itself illustrates how a universal mythos can shift from one era to another.

Astrological Ages

For some today, the concept of the ages can take an astrological form, and this idea has been extraordinarily popular since the 1960s, when the coming of the Age of Aquarius was proclaimed. The idea of the Aquarian Age itself now seems somewhat dated, but that, I would argue, is because we are now actually in the Age of Aquarius, and we take some of its most characteristic features for granted.

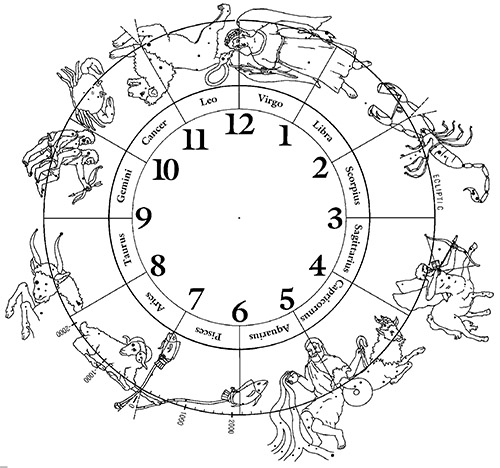

The idea of the astrological ages is based on the precession of the equinoxes, in which, by an extremely long and slow cycle, the point of the sun’s rising at the spring equinox (that is, in the northern hemisphere) moves from one sign of the zodiac to another over a period of nearly 26,000 years. Dividing this by twelve, we can see that each age lasts somewhat less than 2,170 years. Since there is no dotted line in the sky separating one constellation of the zodiac from another, the time of this transition as given by different authorities can vary by centuries. Moreover, there is a tremendous overlap of influences, so that no sharp delineation can be drawn.

Our understanding of the earliest of these ages, which were preliterate, is imperfect, relying on surviving artefacts that may or may not reflect the totality of the culture. It is really only with the Age of Aries, which began in the second or third millennium BCE, that we can begin to fill in details and learn how religious observance in particular has changed throughout these ages.

It’s common to date the recent astrological ages as follows: the Age of Aries, 2100-7 BCE; the Age of Pisces, 7 BCE-2100 CE; the Age of Aquarius, 2100-4200 CE. These dates are highly approximate, although 6 or 7 BCE is sometimes given as the beginning of the Age of Pisces, when a “great conjunction” (between Jupiter and Saturn, opposing the sun) supposedly marked the birth of Christ.

But, on the basis of history, I would suggest that the ages took place much earlier: Aries, between roughly 3000 and 800 BCE; Pisces, between 800 BCE and 1400 CE; and Aquarius, from 1400 CE to, perhaps, 3600. There is also an overlap of several centuries.

My reasoning is as follows: Pisces is associated with religion, and the great world religions all arose around what the German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the Axial Age, the period between 800 and 200 BCE, when figures including the Hebrew prophets, the Greek philosophers, Lao Tzu, Confucius, the Buddha, and Mahavira, the founder of Jainism, all lived.

Thus, by my account, the Age of Pisces marked the birth of all the great world religions, with the possible exception of Zoroastrianism. (Zoroaster’s date is controversial: although his life was traditionally dated to c.800 BCE, scholarly opinion has now pushed it back to the late second millennium BCE.) Judaism and Hinduism certainly existed before the Axial Age, but they changed profoundly during that era. One of the most remarkable changes is that they, like most of the world, gave up animal sacrifice.

Animal Sacrifice In Religion Phased Out

In the Hinduism of the Age of Aries, one of the most important rites was the asvamedha or horse sacrifice. It could only be performed by a king and was meant to ensure the prosperity of the kingdom. The horse was released and allowed to roam for a year; if it wandered into hostile foreign territory, that territory had to be conquered. After its return, it was sacrificed. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad compares the horse to the universe, so that symbolically the universe is sacrificed in this rite.

After the Axial Age, however, the old Vedic animal sacrifices were phased out. The more philosophical and ethical Hinduism that we know today arose, and the sacrifices that were retained (such as the extremely ancient fire sacrifice) did not involve animals. The difference in eras is illustrated by a line from the Hindu Laws of Manu (5:53), which date from the early centuries of the Common Era: “He who sacrifices every year with a horse-sacrifice, and he who eats not flesh, the fruit of the virtue of both is equal.”

Judaism practiced animal sacrifice up until the sack of the Second Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE. And the sacrifice was on a grand scale. Many people have a sugary, children’s-Bible image of the Jerusalem Temple, but the reality was quite different. A text dating probably from around 100 BCE called The Letter of Aristeas gives one of the few surviving eyewitness descriptions of it. One detail that especially impressed the author was the temple’s elaborate plumbing system, which was needed to drain off the blood of all the animals killed.

Animal sacrifice and blood were major themes in the religions of the Age of Aries. Blood keeps surfacing in the biblical narrative; in Genesis 9:6, for example, where God forbids Noah to eat meat with the blood, “which is the life thereof”; a commandment repeated in the Mosaic law, for example in Leviticus 17:11 and Deuteronomy 15:23. Blood, reserved for God alone, is to be poured out on the ground.

The spilling of blood in sacrifice is an ancient and widespread theme. It is treated vividly in the eleventh book of the Odyssey, where Odysseus summons up the shade of the prophet Teiresias to learn how he can return home. Odysseus begins with a huge sacrifice:

I took the sheep and cut their throats over the pit,

and the dark-clouding blood ran in, and the souls of the perished dead gathered to the place…

These came swarming around my pit from every direction

with inhuman clamour, and green fear took hold of me.

When Odysseus wants to speak to the spirits of the dead, he allows them to draw near and drink the blood – or, as we might put it today, the energies given off by the blood.

One might begin to wonder about the nature of animal sacrifice and of the gods that demanded it. Were the gods of the Age of Aries lower-grade spirits that, like the ghosts from Homer’s Hades, literally fed on the life force released from the blood? And did the Age of Pisces, with its more abstract and ethical religions, mark an actual transition to a worship of a higher form of god? (For one view of this transition, see the accompanying article, “Is Your God a Devil?”)

One case of this transition appears in Pythagoreanism, a mystery school founded by the Greek philosopher Pythagoras (c.570-c.495 BCE). Pythagoras enjoined his followers not to eat meat or fish (indeed, until the term “vegetarianism” was coined in the nineteenth century, this was called “the Pythagorean diet”). Nonetheless, in the first century of their existence, the Pythagoreans did not seem to have any problem with the animal sacrifices that were so central to Greek religion; only later, in the fourth century BCE, did this become an issue. This in itself gives a hint of the shift that was taking place in Western consciousness.

Animal sacrifice is still practiced to some degree. Muslims sacrifice domestic animals at the festival of Eid el-Adha. The practice survives as well in Santería and Voudun, the religions of the African diaspora that flourish in the Americas. Years ago in San Francisco, I remember seeing a dead bird on a street corner. It was not the typical grey city pigeon that had dropped dead; it was pure white. I suspect it was the offering of some devotee of Santería who had sacrificed a dove at a crossroads.

Pisces, as we have seen, was the age of the great world religions, and all the major world religions arose during that period, the latest being Islam, which came in the seventh century CE. The most famous symbol of the Age of Pisces is the ιχθυΣ (ichthys) symbol, which is the acronym of the Greek phrase “Jesus Christ, son of God, saviour.” It is the Greek word for “fish.”

The largest and most successful of the Piscean religions (at least in terms of size) are Christianity and Islam, which together account for approximately half of the human race. Both of these posit a monotheistic, personal God who demands obedience, prayer, and ethical behaviour.

Age of Aquarius and the Changing God Image

While the monotheistic God continues to command the belief of much of humanity, another radical change of thought seems to have taken place with the approach of the Age of Aquarius around the beginning of the Renaissance. At that point, humanism began to supplant religion. Humanism has a dual meaning: it can refer to the learning of classical pagan civilisation as well as to a kind of nonreligious philosophy that promotes ethical behaviour without recourse to the supernatural. Both of these began to come to the fore at this time. In the Age of Aquarius – whose symbol is a man – humanity began to focus on a human-centred rather than a divine-centred world.

As I argued in my New Dawn article “The Other Side of Aquarius,” (New Dawn 141) the final transition from the Piscean to the Aquarian age came centuries later, with the great upheavals of the world wars. From a military point of view, these began with naval power dominant (as evidenced by the British Empire) and ended with the triumph of air power (as seen at Hiroshima and Nagasaki). Pisces is a water sign, Aquarius an air sign.

We are thus now in the Aquarian Age. Those who predicted that it would be an age of harmony and understanding were only half-right. It is an age like any other, with its progress and tumult. It is not a dawning millennium that will save us from all our problems; rather it has brought a number of problems of its own – environmental damage, an obsession with computers and technology, and so on.

So we have seen that the previous two ages saw the demise of one set of gods and the rise of another. Who are the new gods of Aquarius?

Aquarius is a rather impersonal sign, as zodiac signs go; it is more comfortable with ideals than with particulars. (It reminds me of a line from Charles Schultz’s comic strip “Peanuts”: “I love mankind. It’s people I can’t stand!”) So it stands to reason that the Aquarian gods would be impersonal as well. And we see that science has pushed aside the creator God of Christianity in favour of abstract entities such as natural selection and the forces of physics. Unlike the gods of Aries, they do not require animal sacrifice. Unlike the gods of Pisces, they do not require worship and moral behaviour. They are completely and utterly indifferent to, and unaware of, the human race.

Science is the dominant mode of thought in the present age. It is taken as the final arbiter of reality and the ultimate determinant of meaning: if science sees no meaning in the universe, then, many would say, there is none. Consequently, the struggle between science and religion is a struggle between the old worldview of Pisces and the new worldview of Aquarius.

From all this, someone might look back and see a steady elevation in conception from the blood-drinking gods of Aries to the moral but vindictive God of Pisces to the bright, shiny new world of science, technology, and progress. There is some truth to this picture – but only some.

We tend to assume that whatever is newer is better, but that itself is a fairly recent development in human thought – and probably Aquarian in inspiration. We’ve already seen how Hesiod portrays the cycle of the ages as one of decay. The classical scholar E.R. Dodds argued that the ancient Greeks had no concept of progress as we know it today. In classical Latin, the word for “new” – novus – had the same pejorative connotation that “old” has for us. In Christian apocalyptic terms too, the present age deteriorates until it can only be saved by the return of Christ. Progress does appear in some Laurasian myths – such as in the Mayan Popol Vuh, which says that the gods created several unsuccessful races until they got it right with humans – but not in very many.

In any event, we can now see Witzel’s Laurasian mythos in its latest incarnation: that of science. There is no creation by God; rather there is a Big Bang. The picturesque ages named after metals have been replaced by immeasurably long and grandiose-sounding ones such as the Precambrian and the Jurassic. And instead of a Götterdämerung or Last Judgment, physicists posit a Big Crunch or heat death as the final fate of the universe.

What remains most striking is that, even in this supposedly objective view of the universe, we have a cosmos that is born, grows up, and dies – just like us. No matter how much intellectual and technical sophistication human beings acquire, they still tend to view the universe as themselves writ large. Is this objectively true – that man is the measure of all things, and our lifespan recapitulates that of the cosmos? Or are we simply foredoomed by our own makeup, with its all-too-finite duration, to see things this way?

I myself go back and forth between these two points of view. In any event, contemporary science faces a fundamental contradiction in its outlook. It holds (1) that our minds are necessarily limited and conditioned by the structure of our nervous system and yet (2) this nervous system, expressing itself in scientific formulae, gives a complete and accurate version of the universe. The Christian theologians papered over their logical contradictions by appeals to divine mystery and the inscrutable will of God. I wonder what escape route the scientists will find.

Finally, the question of meaning remains. Paganism and the world religions did give meaning to the universe. Science, or its quasi-religious form known as scientism, has not. In fact it has gone in the opposite direction. Scientism says not only that it can find no meaning in the universe, but that there is none. Any attempt to find such a thing is derided as a reversion to the supposedly obsolete idea of a personal God.

Are the cultists of scientism right? Science may have squashed simplistic notions of meaning and purpose, but this need persists, and it is not going away. The failure of the new gods of Aquarius to provide it have left our civilisation with a deep sense of anomie and isolation. We can ask how accurate or complete a picture this impersonal Aquarian religion really offers. After all, our very appetite for meaning attests to its existence. You would never feel thirst if there were no such thing as water.

Sources

Arthur Coke Burnell and Edward R. Hopkins, ed. and trans., The Ordinances of Manu, Munshiram Manoharlal, 1995 [1884]

R.H. Charles, ed., The Apocrypha and the Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, volume 2: Pseudepigrapha, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1913

Cherry Gilchrist and Gila Zur, The Tree of Life Oracle, Friedman Fairfax, 2002

Homer, The Odyssey, Translated by Richmond Lattimore, Harper & Row, 1965

R.E. Hume, ed. and trans., The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, 2d ed., Oxford University Press, 1931

G.S. Kirk, J.E. Raven, and M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers, 2d ed., Cambridge University Press, 1983

Rudolf Steiner, “The Occult Significance of Blood: An Esoteric Study”, wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/19061025p01.html; accessed Sept. 16, 2013

E.J. Michael Witzel, The Origins of the World’s Mythologies, Oxford University Press, 2012

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.