From New Dawn 166 (Jan-Feb 2018)

Recently I returned to London after a week in Spain promoting a new translation of one of my books, and taking part in an International Occulture Conference held in León, an ancient city in northern Spain that is an important site on the Santiago de Compostela pilgrim trail. An ‘International Occulture Conference’ you might say? What is that and why in Spain? The second part of this question is easier to answer than the first.

The conference was held in Spain because it was organised by one of that country’s most popular writers, Javier Sierra. While he is not necessarily a household name in the English speaking world, Sierra has had considerable success with some translations of his work, most notably La Cena Secreta (2004) which, as The Secret Supper (2006), found a place on the New York Times bestseller list and stayed there for some time. Other works of what Sierra calls “investigative fiction,” like El Maestro del Prado (2013) – The Master of the Prado (2015) – have also done well in the UK and US. But in Spain Sierra is something of a phenomenon. I got a sense of this at the conference, watching the many fans of his books queue up for him to autograph their copies and to take a selfie with their favourite author.

Sierra’s fictions deal with occult and esoteric themes, but not in a way aimed at shocking or titillating his readers. His books are thrillers, detective stories in the mould of Dan Brown or Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, but what Sierra aims at giving his readers aren’t thrills and shivers but knowledge. He uses the structure of a mystery to uncover the traces of what for convenience sake we can call the Hermetic or Gnostic influence on Western culture. We can say that he uses one mystery to reveal another. At least this is the theme of the two books of his I’ve read. The Secret Supper – translated by Alberto Manguel – deals with the heretical ideas and teachings that Leonardo Da Vinci secretly embedded in his painting The Last Supper, and the efforts of a kind of papal secret police to wipe out those few who can read the code. In The Master of the Prado a young man meets a mysterious older gentleman in Madrid’s famous museum, and is instructed in the subtle art of reading the strange symbolism inserted into some of the world’s most famous paintings, works by Hieronymus Bosch, El Greco, Botticelli, and others.

The knowledge the heroes of Sierra’s fictions acquire is doubly ‘occult’, in that not only is it about ‘hidden’ things – the soul, the spirit world, and visionary states of consciousness, all deemed verboten by the religious authorities – but is itself hidden, coded in a language that only devotees of the lost wisdom can decipher. Sierra’s aim seems to be to teach this language to his readers so they can look at some of the most well-known works of Western art with new eyes, and grasp the deeper meanings that, for the uninitiated, are hidden in plain sight.

What is Occulture?

Here I would say we can begin to answer the second part of our question: what is occulture? It is what happens when what we call the occult and what we know as culture come together, in ways that illuminate both in an unusual light and allow us to understand each from new and different angles. In Sierra’s books Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Kabbalah, art history, hermeneutics and mysticism come together in narratives that not only entertain but instruct.

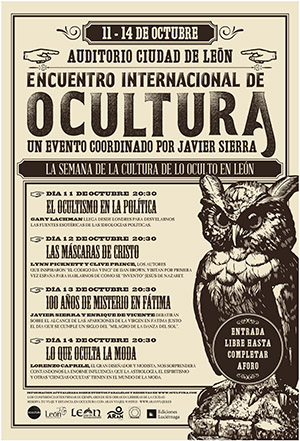

Sierra’s success led to the launch of a new publishing line, Ocultura, which specialises in titles hand-picked by him and whose covers receive his imprimatur. Hence the conference and my appearance at it. My book Politics and the Occult had been chosen for translation as was The Masks of Christ by Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince, who were the other English-speaking presenters at the conference. Picknett and Prince’s The Templar Revelation had been an inspiration for Sierra’s The Secret Supper as it had been for Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code – they even make a cameo appearance in the film. My book looks at the many examples of occult or esoteric ideas that have influenced politics in the modern west, and argues, contra Umberto Eco, that there is plenty of evidence for a ‘progressive’ occult politics, and not only for the more well-known far-right version. In The Masks of Christ Picknett and Prince analyse the actual evidence we have for who exactly Christ was – or wasn’t, as the case may be. As readers of their other books – like The Stargate Conspiracy and The Turin Shroud – have come to expect, their conclusions are, if nothing else, challenging and thought-provoking. The other speakers were Sierra himself, who engaged in a dialogue with the Spanish author and occult mover and shaker Enrique De Vincente on the true meaning of the visions of Fatima, celebrating their hundredth anniversary in 2017, and the top-flight designer Lorenzo Caprile, who spoke about the growing influence of occult ideas in the fashion world.

Politics, religion, haute couture and esotericism do not usually mix, but for the week of the conference they seemed to get on well. The huge León civic auditorium, where the conference was held, was packed and the audience engaged. Local, regional and national newspapers, radio and television covered the event, with shots of the speakers and Sierra standing before the remarkable cathedral at León – a masterpiece of French gothic transported to northern Spain – and at the Basílica de San Isidoro. It claims, among its many other worthy features, to house a good candidate for the Holy Grail, at least according to the historian Margarita Torres Sevilla who argues for its authenticity.1 At the start of our Spanish adventure, in Madrid, I was surprised at the media attention Sierra’s new Ocultura editions drew. Lynn, Clive and I ran a marathon of radio, newspaper, and web interviews, enabled by our excellent translator. But in León there was even more, and when the head of the town council greeted us, I was surprised that he didn’t hand us the key to the city.

Most of this had to do of course with our host’s popularity and the attention and business he was bringing the town, which is already a well-trod pilgrimage site. But it also could not hurt the ‘occulture’ cause, if there is such a thing. I had already taken part in several similar events all held under the occulture banner, in London, New York, and Trondheim, Norway. I had spoken at symposia and conferences in Germany, France, Denmark and Sweden in which the theme was the close links between art and the occult, in the past and present, and had written essays about this for art magazines and catalogues for ‘occulture’ exhibitions held in Europe and South America. So, whatever occulture is, it is certainly getting around.

But what exactly is it? The term occulture is said to have been coined by the performance artist Genesis P–Orridge sometime in the 1980s. What exactly he meant by it remains unclear – at least to me – but it received its academic bona fides some years later. In 2004 Professor Christopher Partridge of Lancaster University defined it as a concern with “hidden, rejected and oppositional beliefs and practices associated with esotericism, theosophy, mysticism, New Age, Paganism,” and other ideas belonging to the “occult subculture.”2

That is indeed a mouthful, but the gist of it was expressed more succinctly by the Swedish writer and publisher Carl Abrahamsson, who summed up occulture as “anything cultural but decidedly occult/spiritual.” Abrahamsson, to whose forthcoming book Occulture I contributed a Foreword, sees this union taking place more in the odd mashups between pop culture and the avant-garde, in the films of the Aleister Crowley devotee Kenneth Anger, the ‘cut-ups’ of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, and other forms of ‘trangressive’ art. But “anything cultural but decidedly occult/spiritual” is a wide brief. It includes, for example, the work of the comic writer Alan Moore, the Russian painter and guru Nicholas Roerich, and the ‘traditionalist’ composer John Tavener. And if Sierra’s ideas are correct, it includes many of the great works of Western art.

To be sure, most self-conscious works of contemporary occulture tend toward the transgressive, the antinomian, for the simple reason they aim to challenge not only the social but the ontological status quo, to upset ‘consensus reality’. As Sierra shows, much of the old traditional art that later rebels transgress against is itself already transgressing – against the religious dogmas and repressions of the time. It is not out to disturb, as by definition transgressive art is, but to instruct. What it wants to trigger is not so much a reaction as a response. It does not want to convey a shock, but knowledge. And to acquire this knowledge it is necessary to know where to look for it and, even more, how to read it. And for this, one must understand the language in which it is written, a symbolic code or lost alphabet that is at the heart of esotericism.

Of course, there is much art that does not qualify as occulture, just as there is much occultism that does not qualify as culture. Occulture inhabits that intermediary realm between the artwork and the ritual, the inner journey and the poetic experience, where the transformative power lies not only in the secret knowledge revealed but in the symbols that convey it. Here knowledge and experience, symbol and symbolised, are one. The magic of a work of art lies first in its power to compel our attention. It is only when it grabs us that we can begin to see it clearly.

The idea of a hidden alphabet or secret code of some kind can be taken too literally, as can the notion of some lost or forgotten knowledge. Then what is sought is some explicit information, some concrete secret – like the password to your bank account – just as military codebreakers seek to decipher the enemy’s messages, which remain meaningless until the key is found. The process, the codebreaking itself is irrelevant; if the information could be obtained otherwise it would be just as useful. The destination, not the journey, is what counts.

Transforming the Imagination

Learning the hidden alphabet of occulture is another matter because here the language and the knowledge revealed through it are one. It cannot be given in another way. The knowledge and the process of acquiring it are one and the same. Because of this, they are transformative.

What brings about this transformation and is itself transformed is the imagination. The artworks at the centre of Sierra’s tales are products of the imagination. But the ability to read them too requires an imaginative effort. Their meaning does not simply pass into our consciousness passively, although to be sure many of us assume that if we stand before an El Greco, a Botticelli, or a Da Vinci, we have ‘seen’ it. But we haven’t. To see in the way that the artist wants you to, and to know what to look for, requires work. It necessitates acquiring what we might call the ‘learning of the imagination’.

That, in fact, is the theme of my recent book, Lost Knowledge of the Imagination, which looks at imagination not as a way of escaping reality or of creating some substitute for it, but as a way of knowing it, as a cognitive faculty. Imagination, I argue, is what enables us to grasp the reality of the world around us in its fullness, which means being aware of dimensions and meanings beyond the physical and sensory, the ‘here’ and ‘now’. This means ‘unseen’ or ‘occult’ dimensions which are nevertheless as real as those revealed through the senses – perhaps more so – but which are grasped not by the senses but by the mind, by what the German writer Ernst Jünger called our “inner claws.” Learning how to grasp in this way is part of the ‘learning of the imagination.’ More times than not the first lesson in this is simply becoming aware that such claws exist and that you possess them. And this means becoming aware of the mind as an active power reaching out into the world and not merely a passive mirror simply reflecting it. This awareness of ourselves as active agents and not merely passive subjects is, I would say, one of the central teachings of esotericism.

Hermetic Wisdom

The Hermetic wisdom that Sierra’s heroes discover in the great artworks of the past says as much. Since the ground-breaking research of the historian Frances Yates, we’ve known that much of the Renaissance and the masterpieces it produced – and which fill museums like the Prado, which I had the opportunity to visit – were informed with the Hermetic belief that man is a microcosm, a little universe, and something more than a wretched sinner. “Within God,” the Hermetic writings tell us, “everything lies in imagination.” Man was made in the image of God and, “If you do not make yourself equal to God you cannot understand him,” so says the universal Mind to its student, the great sage Hermes Trismegistus. The message is clear: the way to God is through the imagination.

Through the translations of the Corpus Hermeticum – the supposed writings of Hermes – by the Renaissance Platonist Marsilio Ficino, ideas and beliefs like these informed the work of masters like Michelangelo. For a brief time it seemed the church would embrace the Hermetic wisdom, seeing in it another expression of the perennial philosophy it itself had emerged from, although it was loathe to admit it. In the end the Hermetic knowledge proved too threatening and, as history shows, was forced underground. Hence the need for the artists aware of these ideas to convey their knowledge secretly, in symbols that only their fellow initiates understand and which pass before the watchful eye of the authorities, seen but not understood. Hence the storyline for Sierra’s ‘investigative fictions’ in which modern-day visitors to the world’s great museums become privy to this lost knowledge, and by learning where and how to look, can read the wisdom hidden for all to see.

Sierra’s message, and perhaps that of occulture, seems to be getting across. When I returned to London I heard the news that he had just been awarded one of Spain’s top literary prizes, the Premio Planeta, for his novel El Fuego Invisible (2017) – The Invisible Fire – which centres around the Holy Grail – which, as mentioned, is believed to reside in León. Most likely this will help the pilgrim business there, and bring in some literary esotourism. Copies of El Maestro del Prado already guide readers to some of that museum’s many treasures, if the stacks of them in the Prado bookshop is anything to go by. Sierra’s belief is that “literature should not only entertain its readers but awaken them.” I would only extend that mission to culture at large, and make it the purpose of art en total.

Footnotes

1. Margarita Torress Sevilla and José Miguel Ortega del Rio, Kings of the Grail: Tracing the Historic Journey of the Holy Grail From Jerusalem to Spain, Michael O’Mara Books, 2015

2. Quoted in Here to Go: Art, Counter Culture, and the Esoteric, ed. Carl Abrahamsson, Edda Publishing, 2012, 7

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.