From New Dawn 153 (Nov-Dec 2015)

An overlooked but powerful current is flowing in our time. It’s found in a small group of writers and thinkers who are trying to overcome the materialism and rationalism of the present age and rediscover the perennial truths that lie behind all religion. These writers are grappling with the occult and esoteric paths of the past and present. They’re trying to explore these movements without falling into either credulity or blinkered scepticism. They include Jay Kinney, founder of Gnosis magazine and author of The Masonic Myth; Mitch Horowitz, a New York book editor whose own works include Occult America and One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life; and Erik Davis, author of TechGnosis and Nomad Codes: Adventures in Modern Esoterica.

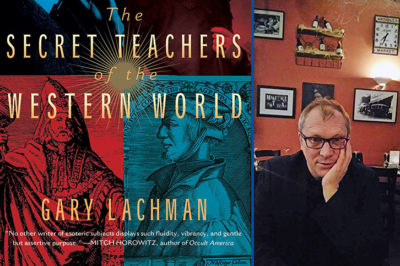

In this small but distinguished company is Gary Lachman. He started out in the 1970s in the New York rock scene as one of the original members of the groundbreaking New Wave band Blondie. In 1996 he moved to London, where he established himself as a full-time writer, contributing to publications such as Fortean Times, The Guardian, and The Times Literary Supplement.

Since 2001 Gary has produced a steady stream of books, including Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius; The Secret History of Consciousness; A Dark Muse: A History of the Occult; and Politics and the Occult: The Right, the Left, and the Radically Unseen. In recent years he has published biographies of major esoteric figures including P.D. Ouspensky, Emanuel Swedenborg, Rudolf Steiner, Carl Jung, and H.P. Blavatsky (see his interview in New Dawn 137).

Gary’s latest work, published in December 2015 by Tarcher/Penguin, is The Secret Teachers of the Western World, a monumental work that unveils the esoteric masters who have shaped the intellectual development of the West, from Pythagoras and Zoroaster to little-known twentieth-century figures such as Jean Gebser and René Schwaller de Lubicz.

In June 2015 I conducted an e-mail interview with Gary about secret currents in the Western tradition.

RICHARD SMOLEY (RS): Many people have a sense, however dim, that what is going on in the news is only the thinnest skin upon a sea of struggles and forces that we can barely conceive of. Would you agree with this assessment?

GARY LACHMAN (GL): I suspect that at most times what we are aware of is only a selection of what is actually taking place. I mean this in the broadest sense possible. In terms of the media, it’s reasonable to assume there are a variety of filters in place that result in an edited version of things getting to us. But then there are people who devote their energies to ‘uncovering’ the truth and ‘revealing’ the facts about this or that event. It does strike me that one could get lost in attempting to track down the ‘truth’ about things, in terms of the political, economic, social situation. I mean conspiracy theorists who pursue an elusive solution to the mystery of who ‘really’ is in power and what ‘really’ happened in this or that situation.

I think it is important to be discriminating about what we accept from our sources and to be aware that every source has its bias. Personally, I am more interested in the kind of things that are outside this kind of ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’, in the philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s phrase. I mean philosophy, thought, etc. I think it’s always a good time to pursue the good, the true, and the beautiful, whoever is running the show. I also think there is less covert control than some people believe, but it seems de rigueur nowadays to feel that everything we see on the news is false. The show itself is ultimately unimportant. It is an unavoidable nuisance that we nevertheless need to be aware of in order to pursue our aims.

RS: Novelist Ishmael Reed wrote, “Beneath or behind all political and cultural warfare lies a struggle between secret societies.” How much truth do you think there is in this statement?

GL: Well, I don’t know. I first came across it, as many people did, in Robert Anton Wilson and Bob Shea’s conspiracy fantasy Illuminatus. Are there really secret societies at work, manipulating events and controlling the world? If there are, they don’t seem to be doing a particular good job of it.

I think that at different times there have been societies or groups of people who have worked together to effect some change or introduce some idea into the societies of their time. I talk about some of them in my new book, The Secret Teachers of the Western World. But these were relatively small groups who were active at a certain time, and when you look at what they were doing, the aura of mystery and sensation around them being ‘secret’ dissolves. That isn’t what is important about them. Take the Fedeli d’Amore of Dante’s time and of whom Dante was a member. They weren’t secret in the way that we think of Skull and Bones or that kind of thing (and I should say here that my book isn’t about that kind of secret group). But they were a relatively private group of poets who wanted to introduce ideas about the divine feminine or Sophia into the consciousness of their time. They were more like what G.I. Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky mean when they talk about the ‘inner circle of humanity’ or ‘esoteric school’. I’m not saying the Fedeli d’Amore were agents of esoteric schools, but that their objectives and practice were like theirs, rather than some cabal of powerful individuals directing events from behind the scenes, which is how secret societies are popularly imagined to be.

In one sense I think conspiracy consciousness is a good sign, in the way that Jung said neuroses were, as an attempt by the psyche to deal with a problem. It shows that we have a hunger for meaning. We prefer feeling that someone is in charge, even if we don’t know who that is, to feeling that no one is and that everything is chance and arbitrary. The hunger for meaning is good; it’s the means of satisfying it that I find questionable. We are purposive beings who seek out patterns and meanings. The mainstream narratives – religion, progress – no longer satisfy our appetite for meaning, and so we seek it elsewhere. One of the ideas of the book is that the meaning is there, but we won’t find it by looking for it outside ourselves.

RS: One period in which occult orders were especially influential was the eighteenth century, in which lodges like the Freemasons played a crucial role in transforming the old feudal and ecclesiastical order into the modern world. Do you have any thoughts or insights about this development?

GL: Freemasonry was a very important means for some fundamental ideas about modernity to be disseminated. I mean ideas about tolerance, social justice, democracy, individual worth regardless of social or economic rank. It was the spread of these ideas through different lodges that helped prepare the eighteenth-century zeitgeist for the radical changes that happened with the American and French revolutions. It is a mistake, though, to think, with Abbé Barruel and more recent writers on the Masonic influence on these events, that Freemasonry arranged or stage-managed them. There were Masons on both sides of the American Revolution, and the Illuminati – the real society, not the popular romanticised idea of it that’s present on the Internet – wasn’t ‘responsible’ for the French Revolution. The ideas that informed Adam Weishaupt’s short-lived and ineffective Masonic offshoot certainly were active forces in the revolution, and they were spread through Masonic lodges. But I think we have to credit the zeitgeist more than Weishaupt and Co. for the storming of the Bastille. In fact in one sense we could say Freemasonry itself was a product of the shift in consciousness that began around that time.

RS: Your new book is entitled The Secret Teachers of the Western World. If they were secret, how have they been able to have such influence?

GL: Well, again, my secret teachers aren’t necessarily secret in the sense that no one knows about them. I mean, if they were that secret, how could I know about them? One can be a secret teacher by teaching secrets, or one can be a secret teacher in the sense that the influence and importance of your ideas haven’t been recognised or have been misunderstood. Or you can be secret in another sense, as with several important thinkers who have been marginalised or don’t fit into the standard model of Western consciousness. It’s a broad term referring to a variable status rather than specific group of people. Jesus Christ, for example, is one of my secret teachers, and most people know about him. But there is a whole school of thought that argues that what we have accepted as Christianity really has little to do with the original teachings associated with Jesus. The Gnostics, for example, are thought to be more in line with what Jesus actually taught then the Petrine church of Rome.

Or take Madame Blavatsky. If people know about her at all, she is chalked up to be an entertaining but fraudulent nineteenth-century spiritualist with a lot of chutzpah. But she was enormously influential on the modern world, in everything from art, religion, and science to what became known as the ‘counterculture’. I am not saying that everything she said about science or religion is ‘true’. That’s not the point. True or not – and she is more often on the ball than you might think – her ideas were tremendously influential, and I am amazed that feminists haven’t appropriated her. I suspect the occult connotations put them off. She isn’t secret, but her influence is not generally recognised.

I should say the central idea of my book is that the whole Hermetic, esoteric tradition is the victim of a war going on inside our heads. I mean the rivalry between our two cerebral hemispheres. One of the inspirations for the book came from reading Iain McGilchrist’s very important work The Master and His Emissary, which is about the left and right brain and the differences between them. Briefly put, McGilchrist revamps the left/right brain discussion by showing that the difference between them is not in what they do – as was originally believed – but in how they do it. They respond to the world in very different ways, and the way they present the world is also very different. In the simplest sense, the right brain presents a total picture of the world. Its mode of consciousness is relational, connective, holistic. It presents what McGilchrist calls the ‘big picture’, the overall pattern, but its picture is fuzzy, vague. It works with metaphor, symbols, and is focused on the living character of being. It is aware of implicit meanings, meanings that we know and feel but cannot express explicitly. (Think of our appreciation of music: we know a Beethoven string quartet means something, but we’d be hard pressed to say exactly what.)

The left brain is aimed at breaking up the big picture into smaller bits and pieces that it can manipulate. Its main function, as Henri Bergson said long ago, is to help us survive. It reduces the living, flowing whole presented by the right brain to a kind of map that allows us to manoeuvre through the world effectively. It’s interested in the trees; the right brain is interested in the forest. One looks through a microscope, the other at a panorama.

Both are necessary, and for the most part each gets along with the other in a system of checks and balances, each inhibiting the other’s excesses. But McGilchrist argues – convincingly, I believe – that in the last few centuries the left has increasingly gained an upper hand against the right and has, in a sense, gone on a smear campaign against it. One expression of right brain thinking that the left brain targeted was the Hermetic, esoteric tradition, which was cast into disrepute with the rise of mechanical science – itself an exemplar of left brain thinking. With the dismissal of the esoteric tradition it was transformed into what the historian James Webb called ‘rejected knowledge.’ What my secret teachers teach is this rejected knowledge.

RS: Of the figures that you would include among these secret teachers, which do you consider the most influential?

GL: That’s difficult to say, and I should point out that the book isn’t a ‘top ten’ or ‘ten best’ list or something like that. Plato is certainly one of the most influential; in many ways the esoteric, Hermetic roads all lead to him. He is believed to have ‘gone to school’ in Egypt, and whatever he learned there is supposed to inform his philosophy. But whether Plato studied in Egypt or not, his ideas about the Forms, the ideal essences of which the physical realities of time and space are merely shadows, is certainly at the heart of the esoteric tradition. And Platonism informed Christianity, Hermeticism, Gnosticism, and other esoteric teachings. We can argue with and reject or accept different aspects or elements of his philosophy, but I would say that for the West, Plato is certainly one of, if not the most, significant source of esoteric thought, or thought in general. Alfred North Whitehead said long ago that all Western philosophy is but a series of footnotes to Plato.

In saying this I’m not saying I think Plato is the ‘best’. My own philosophical background is more in Nietzsche, Bergson, Whitehead, William James, and existentialism. But Plato is still there too.

RS: Which of these figures do you admire the most?

GL: I’m not quite sure how to answer that. There are plenty of admirable figures in the book, as well as more questionable ones, and also some martyrs, like Hypatia the Neoplatonist, and the Persian theosopher Suhrawardi, both of whom fell victim to religious persecution, as well as truly secret teachers like the so-called Dionysius the Areopagite who welded Neoplatonism to Christianity. We do not know who he really was, just as we have no names for the Hermeticists of ancient Alexandria.

I can say who has been an influence on me. One of first writers on esotericism that I read was P.D. Ouspensky. His books Tertium Organum and A New Model of the Universe made a big impact on me, even before I read In Search of the Miraculous and became interested in Gurdjieff. I first read these books forty years ago, and Ouspensky seemed a model of the kind of thinker I wanted to be: he combined a romantic openness to ideas, and poetry and art with a rigorous critical mind and he remains the best writer from what I call the ‘golden age of modern esotericism’, which took place during the 1920s, when people like Ouspensky, Gurdjieff, Rudolf Steiner, Jung, Crowley, and others were all active. Again, I’m not saying Ouspensky is the ‘best’ – that’s as pointless as arguing about who’s the best guitarist. But reading his books excited me and made me want to learn more. I tend to like figures that combine imagination with critical thinking, which we can see as the right and left brain working together, which is another theme running through the book.

RS: One theme that you advance in your new book is that the cosmos is a living, conscious being, and that we need to rediscover that fact. To what extent do you think this rediscovery is actually happening in the world today?

GL: It seems some form of that idea has been revived and presented in a variety of different ways throughout the last century and into our own. Bergson argued a form of it as did Whitehead. In the nineteenth century we have Gustav Fechner, who wrote about the Earth as a living being well in advance of James Lovelock. The philosopher David Chalmers has argued for a kind of panpsychism, meaning that in some sense, the entire universe is conscious. What headway this idea has made in altering our ‘standard model’ of the cosmos is unclear. We’d have to interview lots of scientists, I guess, and go through the numbers. I think more people today have some sense of it than, say, in the nineteenth century – at least the kind of mechanistic picture of the world popular then is less so now. Of course, any scientist who takes the idea literally and talks about it is subject to the scorn of his peers. But that too is an expression of the rivalry between the two modes of thinking. The ‘hard’ left brain makes fun of the ‘soft’ right brain’s ‘need’ to see a nice, cozy universe that cares about him, while he shows how ‘tough’ he is by saying that he doesn’t need that and prefers the ‘truth’ about the cold, indifferent cosmos. I write about this in an earlier book, The Caretakers of the Cosmos, where the idea of a living cosmos is a central theme.

RS: Thirty or forty years ago, it seemed possible to believe that we were on the verge of a new age of rising consciousness and compassion. It’s a little harder to believe this now. How do you personally respond to hopes and dreams of a coming new age (however imagined)?

GL: I’m not that keen on predicting a new age. Western history is littered with them. I think the current pessimism, or, more accurately, nihilism is a kind of ‘sound barrier’ that our culture, our civilisation, has to break through. Nietzsche predicted it at the end of the nineteenth century. I think we have somewhat naïve ideas about a new age. I believe there are shifts in consciousness. One of the thinkers I refer to in the book and in others is the little-known German philosopher Jean Gebser, who talks about different ‘mutations’ of consciousness happening throughout history. But these come about through our own participation in them; I mean we are active players, not passive recipients of something happening in the stars or according to some ancient teachings.

The real new age will come round when we learn how to master our own consciousness. This means coming to understand it. This takes hard, determined work. I don’t think the new age will come about because of nice thoughts or fun raves or because of a conference or a festival. It will start to appear in individuals who have an obscure hunger for some purpose higher or more demanding than what our ordinary life can provide. These types embody in embryonic form a new consciousness that demands a new kind of inner freedom.

We tend to think of freedom as liberation, as being free from something. The new types want a more significant freedom, the freedom for some purpose greater than just fulfilling their individual needs. In The Caretakers of the Cosmos I borrow a term from the Russian existential philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev and talk of a ‘creative minority’. These are the individuals who quietly and solitarily confront the demands of the new consciousness emerging within them. We tend to think that a new form of consciousness will be lots of fun and full of ecstasy. But more often people experiencing a different kind of consciousness, with different needs and appetites, tend to feel like misfits and have to go through a long struggle to actualise their possibilities. I have a very evolutionary way of thinking. I feel that any important development at first makes life more difficult for those in whom it occurs. Those who can get through the initial difficulties develop a strength that will help them impose the new vision on the world around them.

RS: Which living people do you consider to be most important and impressive in fostering this higher awareness?

GL: The most important one for me has been Colin Wilson, who sadly died at the end of 2013 at the age of eighty-two. I have been a dedicated Wilson reader since 1975, when I first read The Occult. After that I tracked down and read as many of his books as I could find. I am in fact preparing to write a book about his work and ideas, which more or less form the basis for much of my own writing. Wilson spent a lifetime in a determined analysis of consciousness and developed what I find to be a very convincing argument for why our consciousness is how it is and what we can do to intensify it. It isn’t for everyone, but I personally have got the most out of following his leads.

Gary Lachman’s The Secret Teachers of the Western World (Tarcher/Penguin) is available from all good bookstores and online retailers.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.