From New Dawn 197 (Mar-Apr 2023)

In the Western media, the Russian philosopher and political analyst Alexander Dugin has been labelled variously as a modern Rasputin, a neo-fascist, a reactionary nationalist, an eminence grise of Putin’s Russia and much else. In order to understand where Dugin is coming from, one has to see him in the light of the time-honoured Russian tradition of the starets, the wise elder, a figure who repeatedly appears in Russian history and literature.

In the run-up to elections for the Russian State Duma (parliament) in 1996, one of the contending parties was the relatively new National Bolshevik Party (NBP), whose emblem was a double-headed eagle clutching a wreath enclosing a hammer and sickle and bearing on its breast an image of Saint Michael spearing a dragon – a combination of symbols that, like the party itself, was calculated to defy all the usual political pigeon-holes.

In one St. Petersburg constituency, a rock concert was organised to support the NBP candidate and at the same time to celebrate the memory of the English magus Aleister Crowley. The star performer was Sergei Kuryokhin (1954–1996), an avant-garde composer and virtuoso pianist. The candidate for the Duma was a young man from Moscow named Alexander Dugin (born 1962), who had been active in the Soviet counter-culture and then became a polemical journalist, publisher and political thinker and activist, achieving fame for his controversial writings on geopolitics. A memorable part of the proceedings was when a moment of silence was observed in honour of Crowley’s memory, after which Dugin read a passage from Crowley’s Book of the Law. Dugin won less than one per cent of the vote in the ballot, and he withdrew from the NBP two years later.

Evidently, Crowley’s concept of magic appealed to Dugin and Kuryokhin because in the previous year they had issued a remarkable joint declaration entitled Manifesto of the New Magi, divided into 22 numbered paragraphs – 22 being the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet and of the Tarot trumps. The manifesto called for a new impulse to overcome the fatigue and degeneracy that had overtaken culture and politics in the modern world. The manifesto declared:

“Magic is not events, things and objects, but causes; magic does not simply describe but actively operates. Magic precedes art and politics. Art and politics became autonomous only upon being detached from their magical source. This source has not disappeared but merely slipped away to the periphery from where it exerts indirect influence. Secret societies, lodges and orders have governed history and inspired artists.… Indirect influence has not been sufficient as politics and art forgot the necessity of constantly appealing to magic. Only the direct, total replacement of art and politics with MAGIC can save the situation.”1

Regardless of the somewhat messianic tone of the manifesto, the authors bring out an important point, namely that the way to influence and motivate large numbers of people is not through logic and reason but through symbols, rituals, drama, archetypes and mythical motifs – in other words through what many would call magic.

Russian Egregores

According to the 19th-century French occultist Eliphas Lévi, magic works through what he called the “astral light,” an invisible, subtle field or fluid that connects all things and can be manipulated by the magician to affect people’s thoughts and behaviour and bring about changes in the world. The concept is similar to akasha in traditional Indian thought as well as to Franz Anton Mesmer’s magnetic fluid, and to what Karl von Reichenbach termed the odic force. While the work of Mesmer and Reichenbach was rejected by the mainstream science of their time, certain of their findings have since gained wide acceptance. For example, the phenomenon of hypnotic trance is now generally recognised by the medical profession as an identifiable state that can be induced both in individuals and in groups, although the exact mechanism by which this works is still a matter of dispute. Several scientists, such as the Russian biologist Alexander Gurwitsch (1874–1954), the German biophysicist Fritz-Albert Popp (1938–2018) and the English biologist Rupert Sheldrake (born 1942), have opened up what has come to be termed a field-based approach, arguing that objects in the physical world, both animate and inanimate, possess fields of energy that give all objects their properties and interact with other energy fields. These interacting energy fields are surely consistent with the notion of an all-pervading etheric fluid, whether termed akasha, the astral light or the od.

I suggest that in this field – call it what you will – are stored the perennial mythical motifs, archetypes and egregores, or collective thought-forms, of a culture. I also suggest that in Russia the veil between this field and the ordinary, everyday world is unusually thin, with the result that these egregores are more vividly present to the Russian mind than they are in most other cultures. In my book Occult Russia, I have identified a number of these egregores, including the notion of Holy Russia, the legend of the faraway Never-Never Land, the figure of the rustic sage and that of the Woman Clothed with the Sun, as described in Revelation. To these I would add another typically Russian figure, that of the starets. In one sense, the word simply means “elder,” but used in the religious context, it means a revered sage, prophet, holy man and often a wandering pilgrim and preacher. Can we consider Alexander Dugin as exemplifying this tradition, and to what extent?

Dugin as a Starets

The starets is often, but not necessarily, a priest or monk attached to a monastery or religious community. Typically these individuals possess great charisma and attract large numbers of people seeking healing, solace, advice for their problems or forecasts for their future. The figure of the starets overlaps somewhat with the rustic sage and also with the holy fool (yurodiviy in Russian), a man or woman who adopts an apparently crazy manner of living and often blatantly ignores conventions but is intensely devout and has miraculous powers of healing and prophecy. Such a one was the 16th-century Saint Basil, who went about naked even in the coldest of weather. These holy fools were also truth-speakers who in certain ways fulfilled the function of the court jester. They were not afraid to speak unpalatable truths, even to a monarch.

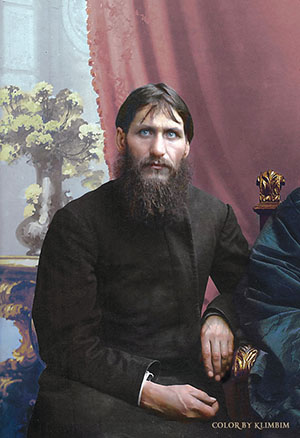

We frequently encounter the starets in the annals of Russian history and the pages of literature. One well-known example from history is Grigorii Rasputin (1869–1916). A whirlwind of a man, part pious visionary, part healer and prophet, part drunkard and reprobate, he is mainly remembered for the way in which he gained the confidence of the royal family, especially the Tsarina Alexandra, on account of his skill in treating the young Tsarevich Alexis, who suffered from haemophilia. On the eve of the revolution, he was murdered by a group of aristocrats, worried by what they saw as his dangerous influence at the court.

Dugin has often been compared to Rasputin, but in fact there is little similarity between them apart from a high degree of charisma. Rasputin was from a peasant family in Siberia and remained illiterate until early adulthood. He was a man of religious fire and piety but not an intellectual. Dugin, by contrast, is a philosopher and a man of immense erudition who comes from a privileged family of the Soviet elite. He is perhaps more readily comparable to another starets, Grigorii Skoworoda (1722–1794), who was born into a Cossack family in a region of the Ukraine that was then part of the Russian empire. Known as the “Russian Socrates,” he was a polymath, philosopher, theologian, composer and much else. After a short teaching career, he became a kind of itinerant sage in the starets tradition.2

In many cases, a person will become a starets after passing through a wild phase in the early years of their life. This was certainly true of the writer Tolstoy, who became a sort of rustic starets in his old age. It is also true of Dugin, who in the 1970s was a member of the Iuzhinsky circle in Moscow, a group of rebellious young intellectuals who went out of their way to defy convention. After perestroika, he explored a variety of different political movements, from the ultra-nationalist Pamyat to the National Bolsheviks. His spiritual path eventually led him to fully embrace the Orthodox religion in the form practised by the Old Believers, a sect that broke away from the main Orthodox Church in the 17th century over doctrinal issues. He also pursued a varied education, including a period of study by correspondence, obtaining a doctorate in sociology. Subsequently, he held a professorship for a time at Moscow State University. By then he had become a celebrated figure, a scholar who could speak with authority on philosophy, politics, culture and religion, and a charismatic public speaker. He had become, in a word, a starets.

To become a starets is to step into a role that has all the force of the corresponding egregore and centuries of tradition behind it. The starets plays partly according to a collectively prepared scenario, but at the same time brings his own particular style and script to the role. Among the various types of starets, two categories stand out: those who care for the souls of individuals and those who address a large audience and proclaim a grand vision. Dugin belongs to the latter group.

He is unusually many-faceted and multi-lingual. One moment he is discussing Nietzsche, post-modernism or the traditionalism of René Guénon, the next he is talking about mythology, geopolitics or the Eurasian movement. He is also equally at home in an academic setting, in a television studio or on the platform at a political gathering. He can talk in the thoughtful, measured tones of a university professor or hold forth like a fiery Old Testament prophet. Highly eloquent, he can hold an audience spellbound. He is the voice of tradition, patriotism, Orthodox piety, profoundly held values and the time-honoured Russian way as opposed to what he sees as the decadent ways of the West.

This is not the place to go into his ideas in detail – his concept of an emerging Eurasian realm, his notion of a perennial conflict between the land powers and sea powers of the world, and his plea for a fourth political theory to replace communism, fascism and liberal democracy. His words are often disquieting, and one may or may not agree with them, yet they can open up fascinating horizons, as when he talks about his concept of “noomachia” (the battle of minds). Here he amends Nietzsche’s dichotomy between Apollo and Dionysus by adding a third deity, namely the goddess Cybele. In a monumental series of some 27 volumes, he explores how these three types of logos, as he calls them, interact in various ways from one culture to another and can give rise to profound cultural differences.

Dugin laments the fact that the wisdom of old age is no longer revered as it used to be. In an interview in 2011, he said:

“In a traditional society an older person was considered to be a role model and a normative figure. Human life was seen to develop from an unreasoning and witless childhood through a foolish and not very focused youth to adulthood and, finally, to the ideal of a fully-fledged person, an elder… But a person was called an elder not so much according to their age, but rather according to their spiritual maturity. Everyone aspired to become an elder. Old age was a state of perfection – one grew towards consciousness, towards the spirit. In our time, we see a radical reversal of this. The role model for society is a young person… a teenager… Infantilism, juvenility, adolescence have become the social norm.”

Dugin paints a bleak picture of a future in which the elderly will have lost all social status and there will be no place for a noble and worthy old age, whether religious, spiritual, or simply wise. “As we modernise, we humiliate and trample the old people more and more. The future takes the place of the past, and the past is scrapped.”3

In a society that ceases to value old age, what is to become of the starets? Despite Dugin’s pessimism the tradition of the starets does not seem likely to disappear any time soon.

One famous example from the cinema screen is the character of the monk Anatoly in the film Island, released in 2006. Anatoly is both a starets and a fool for Christ, who drives his fellow monks to despair through his strange behaviour, but in the end is recognised by them as a true holy man. The part of Anatoly was played by the former rock singer Pyotr Mamonov (1951–2021), who converted to Orthodoxy and became a kind of starets himself. His performance, which has been highly praised by Dugin, had an intensity that could only have been achieved by someone who closely identified with the role. It is a very Russian portrayal of a very Russian phenomenon that is still alive and well, as I believe Dugin himself demonstrates.

The spiritual currents and esoteric traditions of Russia are explored in Christopher McIntosh’s new book Occult Russia: Pagan, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions, available from Inner Traditions.

Footnotes

1. Dugin, Alexander, and Sergei Kuryokhin, “Manifesto of the New Magi” in New Dawn Special Issue Vol. 15, No. 3 (2021), 70-71.

2. See Michael Evdokimov, Russische Pilger. Salzburg: Otto Müller Verlag, 1990, 53-56.

3. The text of the interview is posted on vz.ru/opinions/2011/7/21/508970.html, accessed 20 December, 2022.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.