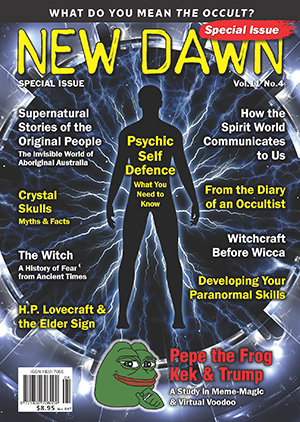

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 11 No 4 (Aug 2017)

Today the popular image of witchcraft in the mass media and in books and magazines is largely defined by ‘Wicca’, a form of neo-pagan witchcraft created by a retired English civil servant called Gerald Brosseau Gardner (1884–1964) in the 1940s. It is now established worldwide as a post-modern, ‘nature religion’ with a spiritual emphasis on Goddess worship. Modern witchcraft, however, did not begin with Gardner and it has a hidden history before Wicca. This history has connections with the famous occultist Aleister Crowley and also with Australia.

From the 1800s onwards there were several revivals of witchcraft in Britain based on historical precedents. These forms of pre-Wiccan witchcraft are variously known today as traditional witchcraft or ‘Traditional Craft’, the ‘Old Craft’ or ‘Elder Craft’, the ‘Sabbatic Craft’, ‘The Nameless Arte’, and ‘The Crooked Path’. There is also plenty of evidence from historical sources, folklore accounts, court cases and, later, newspaper reports in Britain, of the activities of ‘cunning folk’ and other practitioners of folk magic. In popular terminology and belief they were variously known as ‘white witches’, ‘wizards’, ‘sorcerers’, conjurors’, ‘pellars’, ‘planet readers’ (astrologers), and ‘hedge doctors’ (herbalists). These magical practitioners operated widely in both the rural and urban areas of the British Isles and they were consulted by all levels of society from farm labourers to the owners of large country estates.

These cunning folk or ‘white witches’ offered a wide range of services to their clients. They were popularly believed to possess the Sight (the ability to foresee the future and events at a distance, now called ‘remote viewing’ by parapsychologists), exorcise ghosts and banish spirits and poltergeists, cast spells to attract love and money, locate lost or stolen property and missing people using divination or by consulting spirits, and heal the sick using the ‘laying on of hands’ or herbal remedies. Most importantly, as far as their clients were concerned, they could counter the malefic spells cast by so-called ‘grey’ or ‘black’ witches. In some cases the cunning man or wise-woman acted for the general population and the authorities as unofficial witch-finders. However, all types of witches were believed to be able to cure and curse, hex and heal.

Although there are obvious similarities with some of the modern magical practices carried out by Wiccans, most of the methods and techniques used by the old-time witches bear little resemblance to those used by the neo-pagan witches who appear today in the press or on television. Often the cunning folk practised dual faith observance and the charms, amulets, prayers and incantations they used invoked Jesus, the Virgin Mary, the Trinity and the company of saints. Psalms were used for magical purposes as spells and they still are in some modern traditional witchcraft circles. With the coming of the new religion of Christianity and the suppression of ancient paganism, objects such as the cross, saints’ medallions and even holy water were widely used by folk magicians because they were believed to possess ‘virtue’ or magical energy and had inherent healing power.

Christian symbolism was used in folk magic rituals involving psychic protection, counter-magic and healing. Many of the old pagan charms were Christianised and some of the saints took on the earlier attributes of pagan gods and goddesses. Sacred springs previously dedicated to goddesses for instance were re-dedicated either to the Virgin Mary or to female saints such as Winifrede or Bride. Healing charms replaced the names of pagan deities such as Woden, Loki and Thor with God, Jesus and the Holy Ghost. A considerable amount of the old pagan beliefs survived in faery lore. There are many historical examples of witches and cunning folk travelling into a hollow hill, or mountain or visiting a prehistoric burial mound to meet the ‘Queen of Elfane’ (Faeryland). Some mortals entered into ‘faery marriages’ with so-called demon lovers and in return were instructed in herbalism and given the Sight. These gifts were passed down the generations such as in the case of the famous ‘fairy doctors’ or physicians of Mydffai in South Wales.

This knowledge of magical charms, herbal remedies and secret plant lore was often passed down in families either orally or by the medium of written texts. Many of the cunning folk and witches of the 18th and 19th centuries were literate people and had been educated to a stage where they could read and write. Several of the most famous cunning men or wizards were doctors, schoolteachers, small business owners, or even clergymen. Books on magic, fortune-telling and astrology were available and could be purchased mail-order from booksellers in London who specialised in the occult and pornography. In the 19th century several astrological and occult magazines were published and had a wide readership. There is also evidence of hand-written grimoires or magical manuals circulating among witches and magicians. These were similar to the modern Wiccan ‘Book of Shadows’, except that instead of neo-pagan seasonal rituals they contained spells, charms and recipes for herbal remedies.

Because it was widely believed that certain of the cunning folk could ‘smell out’ malefic practitioners of the magical arts, several of the famous cunning men were credited with being able to locate or even control the witches living in their neighbourhood. It was only a short step from this belief to the idea that some of these cunning men might also be ‘witch masters’ – the leaders of their local coven. According to Victorian tales, such covens or covines met in the remote countryside at full moon to worship Old Hornie (the Devil) and practise their evil spells against God-fearing folk who were tucked up in bed. These may have been romanticised accounts, but there is evidence that solitary cunning men and wise-women did meet up with others in their locality to practice magic, swap recipes for spells and exchange occult knowledge. It is logical that to avoid prying eyes such clandestine gatherings would be held at lonely spots in the countryside and on the nights that the moon gave the most light.

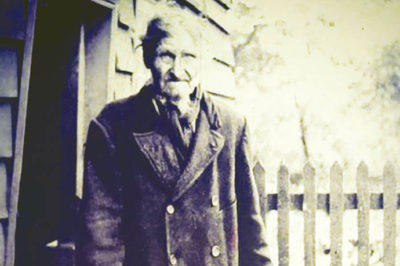

‘Old George’ Pickingill

One of these alleged ‘witch masters’ was the Essex cunning man ‘Old George’ Pickingill (1816–1909), who is also credited with having a role in modern Wicca.1 Pickingill or Pickingale (his surname is uncertain) fitted the stereotyped image of a wizard and was described as “a gaunt, ragged creature, dirty, unkempt, and fierce, with piercing eyes which terrified all who saw him.”2 He was widely feared and respected in the Essex village of Canewdon, where towards the end of his life he lived as a widower and worked as a farm labourer. He was said to possess the Sight, inherited from his Romany ancestors, and could find missing property and see into the future. In addition he had the magical power to summon up elemental spirits to physical manifestation and allegedly would make them cut the hay while he sat in the hedge puffing on his pipe and swigging cider.

The local farmers feared the power of the old wizard so much that they bribed him with beer and food so he would not curse their animals or farm machinery. His landlord also allowed him to stay rent-free in his cottage. It was said that if Old George pointed his blackthorn walking stick, or ‘blasting rod’, at a person they would be paralysed to the spot. They would only be released when the wizard decided. If Old George stood on the doorstep of his cottage and blew a special wooden whistle he owned, all the witches in the village would be forced to come to his bidding and dance in the churchyard. This suggests he was the Magister or master of the local coven.

People who passed Pickingill’s tumbledown cottage late at night and looked in through the dust-grimed and cobwebbed windows alleged they saw the old man dancing with his imps or familiar spirits. The ornaments and furniture also joined in the mad dance like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice sequence starring Mickey Mouse in the Walt Disney film Fantasia. When a woman visited Pickingill when he was dying she reported seeing his imps scampering about on his bedcover in the shape of white mice.

Another source says that Old George was regarded as the ‘Devil incarnate’ by the locals and his family were feared all over eastern England as ‘a race apart’ of witches, warlocks and wizards. It was also claimed that Pickingill was so famous, or infamous, that he was visited by occultists and magicians from all over Europe who sought his advice and instruction.3 When this writer visited Canewdon in 1977 a local resident (then in her seventies) told him that her mother had been a member of George Pickingill’s coven. It apparently consisted of thirteen women with Old George as the ‘Devil’ or male leader. She added that strangers from outside the village and some from ‘far away’ came to consult him because of his occult knowledge and magical powers.

E.W. Liddell, who was initiated into Pickingill Craft in Essex in the 1950s, has alleged that George Pickingill worked in his early life as a horse dealer and used to travel all around southern England. During this period he allegedly founded nine covens led by priestesses he had specially selected because they had the ‘witch blood’ and psychic or magical powers. It is further claimed that in either 1899 or 1900, while he was a student at Cambridge University, the famous ‘black magician’ Aleister Crowley was briefly involved with one of Pickingill’s covens in Norfolk. His mentor in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Allan Bennett, allegedly introduced him to the Craft. It has been also alleged a photograph exists showing Crowley, Bennett and Pickingill together, but it has never emerged into public view.4 Crowley did not last long in the witch coven he joined as he failed to attend meetings. He later told Gerald Gardner, when the two men met in May 1947, that he left because he “refused to be bossed around by a woman.”5

Gardner further told Crowley’s literary executor and first biographer, John Symonds, that the Great Beast was “very interested in the witch cult, and had some idea of combining it with the Order [the OTO or Ordo Templis Orientis], but nothing came of it.”6 When the writer Francis King met Louis Umfraville Wilkinson, a close friend of Crowley’s who officiated at his funeral service in December 1947, Wilkinson told him Crowley said he had “been offered initiation into the witch cult” as a young man.7

It was true that Crowley had been interested for many years in establishing a popular neo-pagan nature religion and it is probable that he and Gardner discussed it when they met. Crowley certainly granted the founder of Wicca a charter to establish a lodge of the OTO, although he did nothing about it. It has even been suggested that Crowley might have considered Gardner as his possible successor as the head of the Order after his death. E.W. Liddell claims that Crowley used a technique of “magical recall” to remember the rituals of the old Norfolk coven and he then passed them on to Gardner.8 It is also said that the New Forest coven into which Gardner was initiated in September 1939 was a surviving remnant of one of the Nine Covens.9 Gardner, however, influenced by the theories of Dr. Margaret Murray, author The Witch Cult in Western Europe (1920), was more interested in promoting witchcraft publicly as a Goddess worshipping, neo-pagan, nature religion for the masses. Neither the image of Old George Pickingill as a ‘cunning man’ or the beliefs and practices of traditional or historical witchcraft, fitted with this radical and innovative concept.

Since Gerald Gardner died in 1964, Wicca, in both its Gardnerian and Alexandrian forms (named after Alex Sanders, the self-styled ‘King of the Witches’) has spread worldwide. It can now be found in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and even Brazil and Japan. In the 1970s an Australian called Simon Goodman (aka Ian Watts) claimed he had been initiated into what he called ‘Sussex Craft’. This has allegedly been brought over to Australia from a village in Sussex in England and was connected with George Pickingill. From the description of its rites and beliefs it seems to have been closer to historical or traditional witchcraft than modern Wicca. A male Magister or Master led the coven and they exclusively worshipped the Horned God (unlike modern Wiccan covens that are mostly Goddess orientated). The ritual implements used in the circle by the Sussex coven included a stang (forked staff), cauldron, a human skull, and a besom.

Wicca & Traditional Witchcraft

What of traditional witchcraft today and the differences between it and modern Wicca? Unlike the average Wiccan, the traditional witch prefers to work outdoors rather than in a cosy, centrally heated, suburban sitting room. For that reason they do not go ‘skyclad’ (naked), preferring robes or cloaks with hoods. This is why traditional groups are sometimes called ‘robed covens’. As one would expect from the fact that they usually work outdoors, the genii loci or ‘spirits of place’, the wights or earth spirits of the land, are very important in their workings.

The mystical concept of the enchanted or sacred landscape is important, because traditional witches regard themselves as the stewards or guardians of ancient sites such as stone circles, standing stones and burial mounds. They will frequently work their rites on or near the prehistoric trackways that mark the ‘spirit paths’, ‘ghost roads’ or leylines that crisscross the British countryside between these natural power centres. However, they are likely to be less sentimental about the environment than Wiccans. They recognise that nature can be ‘red in tooth and claw’ and that the natural laws are based on ‘the survival of the fittest’.

Unlike Wiccan covens that are ruled by a High Priestess with her High Priest as consort and initiation is always male to female or female to male, traditional covines are led by a male leader known as the Magister, Master or Devil, who initiates both men and women into the Craft. The female leader is known variously as the Magistra, Mistress, Maid, Lady, Dame, or Queen of the Sabbat. The Magister has a male deputy called the Summoner who is responsible for organising the dates, times and places for the meetings. Some groups also have a Verdelet or Green Man whose task is to teach the other coveners the secrets of the magical powers and healing properties of herbs and plants.

Within the operative or magical practices of traditional witchcraft one can find the concept of spirit flight (astral projection) to the Witches’ Sabbath, sometimes using the sabbati unguenti or ‘flying ointment’ made from narcotic plants. Techniques of psychic vision, trance, mediumship, ‘true dreaming’ and spirit possession are also used to contact the Otherworld in ways that are allied to ethnic forms of shamanism. Elementals and spirits are summoned and there is communion with the realm of Faerie, the use of familiars, fetches (the witch’s astral double) and spirit guides, shapeshifting into animal form, divination, necromancy, and wortcunning (herbalism).

Some traditional witches follow old-style dual faith observance using the psalms, working with the company of saints and employing Christian imagery, symbolism and liturgy in a heretical and subversive way. This is akin to similar practices found in voodoo and Santeria in North and South America. In common with the witches and cunning folk of the past, the modern traditional witch can both cure and curse as the need arises.

Traditional witches approach divinity in either a duotheistic or polytheistic way. The goddess of the witches has both a bright and a dark aspect, often associated with the waxing and waning of the moon. She can be personified mythologically as Hecate, Diana, Frau Holda, Lilith, or the Queen of Elfane (Faeryland). The witch god is also dual-faced as the Lord of the Wildwood, the Green Man and the Oak King in summer and the Lord of the Wild Hunt, Lord of Death or the Holly King in winter. In mythic terms he is represented as Herne, Wayland, Puck or Robin Goodfellow, Tubal Cain, Sylvanus, Lucifer, or the King of Elves. He also appears in animal form as a stag, bull, goat, ram or a black dog. Many traditional witches prefer not to associate their deities with any mythology. Instead they refer to them obliquely as the Old Ones, the Owd Lad and Owd Lass, the Old Man and the Old Woman, the Lord and Lady, the Horned One, the Devil, the Old Dame, or just Him and Her.

Although a few traditional and hereditary witches (those belonging to a family tradition) have come out of the shadows in recent years, they are more reluctant than Wiccans to seek publicity. They are not likely to appear on daytime television wearing crushed velvet robes, waving knifes and swords and covered in occult bling. In fact they often look surprising normal, wear ordinary clothes and blend into the background. Because they possess a fund of knowledge about the stars, trees, plants, ancient history and the weather, people may just think they have a keen interest in country matters, nature and folklore.

Wicca obviously attracts many people, especially those seeking a trendy ‘green’ form of spirituality that worships nature. Those who follow the Old Craft today do not regard themselves as ‘nature worshippers’. Many actually do not believe it is a religion per se, and certainly not a ‘nature religion’. Instead they regard it as a mystery cultus offering an ancient heritage of forbidden wisdom and occult (hidden) knowledge. It is a mystical path that leads to spiritual enlightenment and ultimately to gnosis and union with the Godhead. It represents a bright lantern shining in the dark for those dedicated seekers to follow who still seek the ancient Mysteries in the modern world.

Footnotes

- E.W. Liddell, The Pickingill Papers: Old George Pickingill and the Origin of Gardnerian Wicca (edited and annotated by Michael Howard), Capall Bann UK, 1994

- Eric Maple, The Dark World of the Witches, Robert Hale Ltd UK, 1962, 185

- Charles Lefebure, Witness to Witchcraft, Ace Publishing USA, 1970, 51-54

- Liddell, 21

- Jack Bracelin, Gerald Gardner: Witch, Octagon Press UK, 1960, 158

- Letter in the Gerard Yorke Collection at the Warburg Institute, London quoted in Professor Ronald Hutton, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Neo-Pagan Witchcraft, Oxford University Press UK, 1999, 219

- Francis King, Ritual Magic in England, Neville Spearman UK, 1970, 140-141

- Liddell, 160

- Liddell, 23

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.