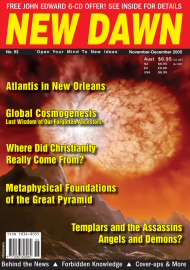

From New Dawn 93 (Nov-Dec 2005)

Following the success of The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown’s earlier work Angels and Demons has been discovered by fans who are now fascinated by references to the medieval secret society known as the Order of Assassins. This group triggered exceptional public interest in the last few years, particularly after the September 11 attacks when the media was rife with accounts of the Assassin-like Al-Qaeda group. Public curiosity in the actual Assassins was at an all-time high and interest has not yet abated.

While there have always been people fascinated by secret societies, James Wasserman, author of The Templars and the Assassins: The Militia of Heaven,1 believes contemporary interest in this area has peaked under the effect of two main social factors. The first is the breakdown of traditional religion prompting people to look for alternative theology, or in Dan Brown’s case, alternative re-readings of traditional religion. This is certainly a more popular option for the majority of thinkers who would rather not step too far away from their comfort zone. The second factor put forward by Wasserman is the increasing power of separatist groups within the socio-political life of world affairs. Political protocols are now limiting the actions of large governments who move too slowly to compete with smaller, more dynamic groups. As these smaller groups gain more ground, they trigger public interest and in some cases, public fear.

Many influential groups started in a similar fashion. The famous Templar Knights were at first a small group of nine French knights who kept every action hidden under the radar of the established authorities. Within the conditions of secrecy they built the basis of a network that later extended across Europe. Wasserman believes the Assassin Order was created through the same process and had a great deal in common with the more well known Templars. Many scholars actually point to the Assassins as a seminal forefather of the secret society model, and as more evidence comes to light researchers are beginning to realise the Assassins were more influential and innovative than they were ever given credit for.

The Assassins are infamous for their political murders. They created the concept of the ‘sleeper agent’ and pioneered the practice of training and placing operatives who would lay dormant within their environment, later spurred to action by a distant commander.

The Old Man of the Mountain

When the Prophet Muhammad died in 632 without having designated a successor to lead the community he founded, many Muslims believed his son-in-law and cousin Ali to be his legitimate successor. Over time this group, known as the Shi’atu ‘Ali, or party of Ali, divided from the majority Sunnis who followed Caliphs chosen by the consensus of the community. Centuries later a breakaway from the Shias, the Ismailis, founded the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt. A schism arose when the rightful Fatimid leader Nizar was imprisoned and supplanted by his younger brother. Hence, the followers of this subsect were called the Nizari Ismailis.

The Nizari Ismailis are believed to have adopted elements of the Sufi tradition and its mystical symbolism, best known through the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Part of the Nizari sect took on a proactive military function with the aim of ensuring the survival of the Nizari as a whole and also working toward shifting the political scales in their favour.

The founder of this militant group was a Persian called Hasan-i-Sabbah, born of lower middle class parents at Rayy, an old city a few kilometres to the south of modern Tehran in approximately 1060. A dedicated Ismaili, in 1090 he united the entire movement and took possession of a stronghold in Khorassan which became headquarters for the Order and known as Alamut, ‘the eagle’s nest’. Once established in a secure and permanent base, Hasan sent his agents out from Alamut in all directions, while at the same time pursuing a policy of territorial expansion, taking surrounding camps by force.

Marco Polo claimed he passed Alamut in 1271 and described the splendour in his travel diary:

In a beautiful valley, enclosed between two lofty mountains, had formed a luxurious garden stored with every delicious fruit and every fragrant shrub that could be procured. Palaces of various sizes and forms were erected in different parts of the grounds, ornamented with works of gold, with paintings and with furniture of rich silks. By means of small conduits contained in these buildings, streams of wine, milk, honey and some of pure water were seen to flow in every direction. The inhabitants of these places were elegant and beautiful damsels, accomplished in the arts of singing, playing upon all sorts of musical instruments, dancing, and especially those of dalliance and amorous allurement. Clothed in rich dresses, they were seen continually sporting and amusing themselves in the garden and pavilions, their female guardians being confined within doors and never allowed to appear.2

Polo also put forward his explanation for the purpose behind such an impressive display.

The object which the chief had in view in forming a garden of this fascinating kind was this: that Mahomet having promised to those who should obey his will the enjoyments of Paradise, where every species of sensual gratification should be found, in the society of beautiful nymphs, he was desirous of it being understood by his followers that he also was a prophet and a compeer of Mahomet, and had the power of admitting to Paradise such as he should choose to favour.

Hasan had an excellent knowledge of theology, and the energy and allure needed to influence the minds of his contemporaries. He patiently prodded a potential candidate’s religious doubts until they were weak enough to admit the possibility of an alternative. Over time he managed to create a vast group and a powerful sectarian sense of community based on secrecy and conspiracy.

According to the legend popularised by Marco Polo, the fortress court held boys as young as twelve years old who Hasan thought destined to become courageous men. When he sent them into the garden in groups of four, ten or twenty, he gave them hashish to drink where they slept for three days. It is thought they were carried sleeping into the garden where he had them awakened.

Marco Polo, based on what he had heard about the Assassins, wrote:

When these young men woke, and found themselves in the garden with all these marvelous things, they truly believed themselves to be in paradise. And these damsels were always with them in songs and great entertainments; they received everything they asked for, so that they would never have left that garden of their own will.

And when the Old Man wished to kill someone, he would take him and say: ‘Go and do this thing. I do this because I want to make you return to paradise’. And the assassins go and perform the deed willingly.

The strongest source of information on the Assassins came long after the Order fell from influence. Following the eventual demise of their headquarter stronghold in Alamut, volumes from their amazingly extensive library were examined by the Persian scholar Jawani, who later wrote a careful book in which he detailed the organisation of the Order. Their name has been attributed to the Arabic hashshashin meaning “consumer of hashish,” which they were said to use in the Initiation ritual. This is one of numerous explanations for the name of the sect, none of which can be confirmed. Assasseen in Arabic signifies ‘guardians’, and some scholars have considered this to be the true origin of the word: ‘guardians of the secrets’. There is no mention of hashish in connection with the Assassins in the library of Alamut. Even the most hostile Islamic writers of the time, both Sunni and Shia, nowhere accused the Assassins of drug use.

Jawani’s account of the library of Alamut became the main reference for study of the Assassin Order. The only other sources are the few sparse accounts of the day, one of which came from a visit by Count Henry of Champagne to the stronghold of the Assassins in 1194. Following the murder of the Latin King of Jerusalem at the hands of the Assassins in 1192, Henry was appointed his successor and as a result was eager to negotiate a truce with the Assassins to avoid a similar fate. At a palace in the Nosairi Mountains Henry met the Assassin Master. Also popularly known as the Sheikh or ‘Old Man’ of the Mountain, he claimed that he did not believe Christians were as loyal to their leaders as his disciples were to him. He demonstrated his point by signalling to two young men standing high above on the palace towers. Immediately they leapt to their deaths on the mountain rocks below. It was written that Henry arrived from his visit “visibly shaken” by the ordeal of this contact.

Influence on the Templars

Dr. F.W. Bussel in Religious Thought and Heresy in the Middle Ages writes that it cannot be disputed the Templars had “long and important dealings” with the Assassins “and were therefore suspected (not unfairly) of imbibing their precepts and following their principles.”3

Islamic culture of the day was a great deal more refined than that of Europe during the Dark Ages. The Templars along with all Europeans in the area were greatly affected by their contact with the Muslim East. They learnt the daily customs, the languages and business practices, discussed philosophy, and lived amongst what must have seemed an almost alien culture. In time, Templar ranks contained people who had spent more time in the Middle East than in Europe, and some who had little or no memory of European life, custom and philosophy.

Under these conditions, the initial contact between the Templars and the Assassins occurred. “As the systematic overturning of Muslim Shariah took place among the Syrian Nizaris, some sense of the subtlety of their beliefs may have been communicated to their new acquaintances,” observes James Wasserman.4

By this time, the Assassins had already rejected Islamic dogma and acquired the heretic tag. Later the Templars would also find themselves denounced as ‘vile heretics’. Assassins became known to the Muslim world as Ta’limiyyah or “people of the secret teaching.” The idea that they were the guardians of a secret or inner doctrine had always been promoted by Hasan, and they were feared and revered for this very reason.

Branded as heretics, the Templars met their end in the 14th century. One of the charges levelled against the Templars was they kept “secret liaisons with Muslims,” and were accused of “being closer to the Islamic faith than to the Christian.” In reality, the Templars had found a mirror image of themselves in the mysterious Order of Assassins, and held the Western face of the same esoteric doctrine. It was even written that a number of Templar Knights were initiated by the Assassin Master, while others were given standing rank, so close was their secret teaching considered.

The Organisational Model

The Christian Order of the Knights of Templars, who came into contact with some of Ben Sabbah’s commanders during the Crusades… were reputed to have adopted Ben Sabbah’s system of military organisation.5

The organisation of the Assassin Order called for missionaries and teachers known as da’is, the disciples and spiritual followers known as the rafiqs, and the fidais or devotees who in practice were the trained killers. The fidais were not part of the original Ismaili model, but were later added by Hasan. The Templar hierarchy is said to be derived from this model and can be easily compared, where the Assassin offices of da’is, rafiqs, and fidais correspond to the Templar degrees of Novice, Professed, and Knight.

The Templars assimilated the system but adjusted the core symbolism to their own purposes. Where the levels used in the Assassin model denoted particular functions and duties, the Templar levels further developed the concept of progressive learning and acquired skill, similar to the modern military ideas of private, corporal, and general. Every Templar Knight was, at one point, a novice, and a professed member, but not every Assassin was a da’is or a rafiq. In fact it was said that Hasan would never let a candidate become a fidais who had sufficient intellect to become a missionary. The spiritual man stood above all others in the Order.

The Assassins believed they held the secret or inner Islam, a completely esoteric component unavailable to those uninitiated in their philosophies. Their system of organisation was developed to both guard the secret doctrine and strictly control the continuance of the teaching. A number of schools were established practicing this organisational model, including secret rites and rituals. Members were enrolled on the understanding they were to receive hidden power and timeless wisdom that would enable them to become as important in life as some of the great teachers.

Hasan enlisted young men between the ages of twelve and twenty from the surrounding countryside. Each day he held court where he spoke of the delights of Paradise. It was said that Hasan would often buy unwanted children from their parents, and train them in line with his purposes. The Order was an organisation of the common people of the land, far removed from the typical aristocratic blueblood that petitioned for the Knights Templar mantle.

Another regular activity of the Assassins was the kidnapping of useful, rare and distinguished personages who could be of value to them in educational, military or other spheres and holding them captive in Alamut. These prisoners were respected physicians, astronomers, mathematicians and painters. Assassins coveted knowledge the way the Templars seemed to covet spirituality, although they were separated by the Assassin’s willingness to take knowledge indiscriminate of context, at any cost and by whatever means.

It is true that both the Templars and the Assassins shared a policy of secrecy. Their teachings were kept for the eyes and ears of initiates only. Comparisons with the Essenes, Cathars, and Sufis spring to mind as similar attempts to release the esoteric heritage of the soul. In the past, these enlightened groups existed without knowledge of each other, but the Crusades caused two of these groups to meet, comparing doctrines and making alliances.

The Legacy

Following the destruction of Alamut by Hulegu in 1256, members of the Order are thought to have fled to Afghanistan and the Himalayas. Many of them journeyed to India where the Nizari Ismaili community flourished under the leadership of the Aga Khans. Other groups have been put forward as possible candidates for the legacy of the Assassins, but the true legacy of Hasan-i-Sabbah is his seamless creation, both religious and political. In this wider sense the thought and doctrines of the inventor of the Assassins may be said to have an enduring influence in the religious and political life of the Middle East.

The Templar Order is believed to have refined their approaches under the direct influence of Eastern philosophy, and in confronting another group on the opposite side which existed to safeguard the same ancient teachings. According to Julius Evola, the Crusades, in many respects, created a “supratraditional bridge between West and East” where the Templars were the “Christian equivalent of the Arab Order of the Ishmaelites (Ismailis).”6

Unfortunately, the Templars and the Assassins did not write the history books, and thus they have fallen to the state of Demons rather than Angels, while the authorities of the day are remembered in glowing terms. Yet, despite this, as James Wasserman concludes:

The legends of the Templars and the Assassins are indeed very much alive to this day. The long-term survival of the memory of these two rather obscure groups points to various archetypal levels at which they affect the psyche. Meditation on certain concepts may help us better to understand this. Despite the best efforts and tenacity of the modern secular campaign to disparage traditional beliefs and ideals as either outdated or based on erroneous assumptions like God – traditional values somehow survive. The “innate knowledge of the Gods” described by Iamblichus demands of us that we aspire to honor, chivalry, self-sacrifice, redemption, patriotism, courage, and integrity. What better words could be used to describe the ideology shared by the Templars and Assassins of yore?7

Footnotes

1. Wasserman, James, The Templars and the Assassins, 2001, Destiny Books, USA.

2. Polo, Marco, Travels in Asia, 1938, G. Routledge, London.

3. Bussel, F.W., Religious Thought and Heresy in the Middle Ages, 1918, R. Scott, London.

4. Wasserman, James, The Templars and the Assassins, 2001, Destiny Books, USA.

5. O’Ballance E, Language of Violence: The Blood Politics of Terrorism, 1979, San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, p. 4.

6. Evola, Julius, The Mystery of the Grail: Initiation and Magic in the Quest for the Spirit, 1996, Inner Traditions, USA.

7. Wasserman, James, The Templars and the Assassins, 2001, Destiny Books, USA.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author. For our reproduction notice, click here.