This article was published in New Dawn 170 (Sept-Oct 2018)

The masterfully told stories of a magical nanny that held adults and children alike spellbound for decades might incline readers to think that Australian author Pamela (P.L.) Travers merely had an over-active imagination. The truth is that her talent blossomed out of a fertile garden of occult teachings and paranormal experiences, nurtured and inspired by some real-life, exceptionally gifted personalities.

The movie Saving Mr Banks and the documentary The Real Mary Poppins treated the public to insights into her relationship with her father, the influence of the Auntie she called Sass, and her tumultuous association with Walt Disney. Of equal gravity was her lifelong attraction to mystical pursuits and the guidance of the philosopher and mystic George (G.I.) Gurdjieff.

Travers was born in Maryborough, Queensland, as Helen Lyndon Goff in 1899. Her father, Travers Robert Goff, whom she adored, moved the family to the small community of Allora on the Darling Downs in 1905, where he died of tuberculosis at the age of 43. It was then that Christina Saraset, or Aunt Sass as she liked to be called, came on the scene to help out, and Pamela and her family moved once again, this time to Bowral in New South Wales.

It is now common knowledge that the character of Mr Banks in her novels was based on her father, Travers Goff, while Aunt Sass, who ‘flew in from the east’, would serve as the model for Mary Poppins herself, who famously blew in from the east with her parrot umbrella and magical carpetbag. The real-life Aunt Sass was a strong, no-nonsense presence in her niece’s life, as well as her work. Travers described her as a “bulldog with a ferocious exterior” but with a “heart tender to the point of sentimentality.”

Pamela Travers has been described by some observers as “mysterious and prickly,” and one could form the opinion, based on Emma Thompson’s portrayal of her – as praiseworthy as it was from an artistic point of view – that the writer was full of herself, close-minded and perhaps even emotionally cold. And this notion might be further reinforced by the fact that she never married, bore children of her own or formed a family unit in the conventional sense. Yet such an impression would be completely false.

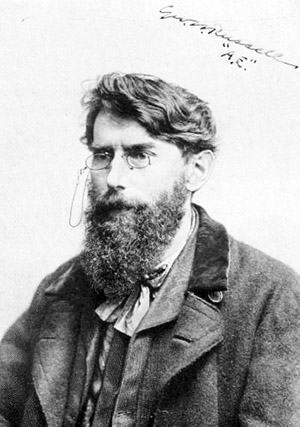

As a young woman Helen Goff was an actress, dancer and a poet before turning her hand to journalism. She toured Australia and New Zealand as a member of Allan Wilkie’s Shakespearean Company, adopting the stage name Pamela Lyndon Travers. At the age of twenty-four she travelled to Ireland, where the Irish poet and mystic George (A.E.) Russell became her mentor. As editor of the Irish Statesman, Russell, whose kindness towards younger writers was legendary, initially accepted some of her poems for publication. From 1925 onward she was introduced to Theosophical thought and literary figures familiar with the Theosophical Society, including T.S. Eliot, Oliver St. John Gogarty and William Butler Yeats, the latter being one of the leaders of the Golden Dawn.

Gurdjieff, Mysticism & Spirituality

Travers studied the Gurdjieff system under Jane Heap, and in March 1936, with the help of Jessie Orage (widow of The New Age editor Alfred Richard Orage), she met the mystic George Gurdjieff, who in turn introduced her to the paths of Sufism and Zen. He encouraged her to explore Eastern religion and, during her thirties and forties, she delved into Buddhism, later gravitating to Jiddu Krishnamurti.

The successful writer travelled to New York City during World War II while working for the British Ministry of Information. At the invitation of her friend, the US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, Travers spent two summers living among the Navajo, Hopi and Pueblo Indians, studying their mythology and folklore.1 Episodes such as these reveal something of Pamela Travers’ true character and her perpetual thirst for occult knowledge. She had no qualms about lodging at a reservation and formed a close bond with the Navajo people in Arizona who did the honour of bestowing an Indian name on her, although it was one that she always kept secret.2 After the war, she remained in the USA and became Writer-in-Residence at Radcliffe College and Smith College, Massachusetts.

Journalist and critic Jerry Griswold, in an essay tribute to Pamela Travers after her death, asserted that she had “lived for several years” with the Navajos and, during another period, had “studied for several years” in Kyoto under a Zen master,3 although in his recollections he probably exaggerated the time spans somewhat. After her American sojourn, she returned to England, making only one brief visit to Sydney in 1960 while on her way to Japan to study Zen mysticism.

Arcane Influences & Didactic Writings

The question arises as to what degree the writings of Pamela Travers were influenced, guided or even manipulated by her spiritual masters? She met George Gurdjieff some years after the first edition of Mary Poppins had been published (in 1934), followed by the equally well-received Mary Poppins Comes Back (1935). Any direct influence by Gurdjieff is more likely to be found in the later Mary Poppins books, particularly Mary Poppins Opens the Door (1944) and Mary Poppins in the Park (1952).

In 1970 Pamela Travers authored a contribution on Gurdjieff for Richard Cavendish’s encyclopedia Man, Myth & Magic (see page 48), then went on to publish an insightful ten-page booklet George Ivanovich Gurdjieff three years later. In that tract she reflects on the various traditions that were woven into Gurdjieff’s work and, by extension, her own thought and philosophy:

What was the source of his teaching? True to his role, Gurdjieff never openly disclosed it. By examining his writings and the numerous commentaries upon them it might be possible to discover parallels in various traditions: Tantric Buddhism, Hinduism, Sufism, Greek Orthodoxy – possible, but hardly profitable. For the fundamental features of his method cannot be traced to any one source. Ouspensky quotes him as admitting, I will say that, if you like, this is esoteric Christianity. There seems no reason to reject this when one remembers that Christianity, as Gurdjieff knew it, was the heir of the ages and must have drawn to itself elements from very early pre-Christian traditions, Hittite, Assyrian, Phrygian, Persian; and there is nothing so explosive as old ideas restated in contemporary terms as the Western world was to discover when Gurdjieff burst upon it.4

In the same publication she lists several celebrated editors and writers of the day who socialised with Gurdjieff:

Great feasts where, under the influence of good food, vodka and the watchful eye of the Master, opportunities were provided, for those who had the courage, to come face to face with themselves. The hardiest among them, those who could rise to the level of being serious, were allowed to transmit something of the teaching to newer pupils.5

This issue of the transmission of the teachings poses the further question as to whether the novels penned by Travers carried veiled arcane messages intended only for the more astute, esoterically inclined among her audience. We should, nevertheless, resist the temptation to read too much of Gurdjieff into the Mary Poppins’ stories. In an interview which appeared in the Paris Review in 1982, the interviewers asked Travers whether “Mary Poppins’ teaching – if one can call it that – resemble that of Christ in his parables.”6 Travers replied: “My Zen master, because I’ve studied Zen for a long time, told me that every one (and all the stories weren’t written then) of the Mary Poppins stories is in essence a Zen story. And someone else, who is a bit of a Don Juan, told me that every one of the stories is a moment of tremendous sexual passion, because it begins with such tension and then it is reconciled and resolved in a way that is gloriously sensual.” The answer is clarified by the following question (posed by the interviewer): “So people can read anything and everything into the stories?” Travers’ response: “Indeed.”

In Man, Myth & Magic, Pamela Travers wanted to make it clear that the work of her Master in no way constituted Black Magic. She wrote:

It is clear from Gurdjieff’s writings that hypnotism, mesmerism and various arcane methods of expanding consciousness must have played a large part in the studies of the Seekers of Truth. None of these processes, however, is to be thought of as having any bearing on what is called Black Magic, which, according to Gurdjieff, “has always one definite characteristic. It is the tendency to use people for some, even the best of aims, without their knowledge and understanding, either by producing in them faith and infatuation or by acting upon them through fear. There is, in fact, neither red, green nor yellow magic. There is ‘doing’. Only ‘doing’ is magic.” Properly to realise the scale of what Gurdjieff meant by magic, one has to remember his continually repeated aphorism, “Only he who can be can do,” and its corollary that, without “being” nothing is “done,” things simply “happen.”7

Travers insisted that the Mary Poppins stories had not come from herself but that there are “ideas floating around that pick on certain people.” She believed that her books were gifts of God, “given” to her, and quoted C. S. Lewis saying, “There is only one Creator, we merely mix the ingredients He gives us.”8 She declared that she was not a creator, simply a vessel, and never wrote specifically for children but was “grateful that children have included my books in their treasure trove.”

What the Bee Knows

In addition to her well-known collection of novels, Pamela Travers wrote numerous non-fiction essays and books, especially in her later years. What The Bee Knows is a collection of spiritual essays. The back of the book describes it as “a honeycomb of essays pointing to the truth-of-things handed down in the great popular stories of cultures around the world.” And that is just what it is, a labyrinth of brief dissertations covering a range of esoteric, myth-based and biographical themes. She shares tales of her friendships with literary figures such as W.B. Yeats and A.E. Russell, of her studies among many religions of the world, of her early experience with fairy tale and folklore which shaped her character.

The Sphinx, the Pyramids, the stone temples are, all of them, ultimately, as flimsy as London Bridge; our cities but tents set up in the cosmos. We pass. But What The Bee Knows, the wisdom that sustains our passing life – however much we deny or ignore it – that for ever remains.9

Why did Pamela Travers choose the Bee as her metaphor? She wrote:

I thought of Kerenyi – “Mythology occupies a higher position in the bios, the Existence, of a people in which it is still alive than poetry, storytelling or any other art.” And of Malinowski – “Myth is not merely a story told, but a reality lived.” And, along with those, the word “Pollen,” the most pervasive substance in the world, kept knocking at my ear. Or rather, not knocking, but humming. What hums? What buzzes? What travels the world? Suddenly I found what I sought. “What the bee knows,” I told myself. “That is what I’m after.”

But even as I patted my back, I found myself cursing, and not for the first time, the artful trickiness of words, their capriciousness, their lack of conscience. Betray them and they will betray you. Be true to them and, without compunction, they will also betray you, foxily turning all the tables, thumbing syntactical noses. For – note bene! – if you speak or write about What The Bee Knows, what the listener, or the reader, will get – indeed, cannot help but get – is Myth, Symbol, and Tradition! You see the paradox? The words, by their very perfidy – which is also their honourable intention – have brought us to where we need to be. For, to stand in the presence of paradox, to be spiked on the horns of dilemma, between what is small and what is great, microcosm and macrocosm, or, if you like, the two ends of the stick, is the only posture we can assume in front of this ancient knowledge – one could even say everlasting knowledge.”10

An Esoteric and Occult Bequest

Toward the end of her life Travers became increasingly interested in Sufism, a form of Islamic mysticism, particularly the Persian branch of it, through meetings with members of the fraternity and their publications in Britain. We can assume that she continued her search for life’s meaning among the world’s mystical and spiritual traditions right until the end. Perhaps she never felt she had reached the ultimate aim of Gurdjieff’s Work or ‘Fourth Way’, which held the goal of shattering one’s pretensions and ego, the stripping away of the personality and awakening to a higher consciousness.

It is no secret that the great success of author J.K. Rowling with that other fictional champion of magic in book and film, Harry Potter, owes something to Pamela Travers. Rowling was an admirer of Travers and adopted both her enigmatic disguise in initialling her first names and also her theme of flight, just as Travers had herself been inspired by J.M. Barrie’s ‘Peter Pan’. Rowling now ranks highly in the tradition of authors of youth fantasy classics, joining C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, J.M. Barrie and, of course, P.L. Travers. She also borrowed the name when she created the character of the Death-Eater wizard called Travers in her novels, portrayed by actor Tav MacDougall in the film adaptation of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.

In 1977 Pamela Travers was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire and in 1978 received an honorary degree from Chatham College, Pittsburgh, USA. She would spend the final years of her life in London’s Chelsea district, dying from the effects of an epileptic seizure, on 23 April 1996 at the age of ninety-six. What she contributed to literature is now legendary. What she bequeathed us in the way of mystical knowledge ought not be underestimated either. Her lifelong pursuit of spiritual wisdom significantly enriched the storehouse of esoteric teachings available to all those she called the ‘Seekers of Truth’.

Footnotes

1. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._L._Travers

2. www.biography.com/people/pl-travers-21358293

3. Revealing Herself to Herself: REMEMBRANCES by Jerry Griswold, Los Angeles Times, 16 June 1996

4. www.gurdjieff.org/travers1.htm

5. Ibid.

6. As quoted by Massimo Introvigne at: www.academia.edu/29792559/Mary_Poppins_goes_to_Hell_Pamela_Travers_Gurdjieff_and_the_Rhetorics_of_Fundamentalism

7. “Gurdjieff” in Man, Myth and Magic: Encyclopedia of the Supernatural (1970)

8. www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-p-l-travers-1306698.html

9. What the Bee Knows: Reflections on Myth, Symbol, and Story by P.L. Travers (1989)

10. “What the Bee Knows” in Parabola: The Magazine of Myth and Tradition, Vol. VI, No. 1 (February 1981); later published in What the Bee Knows: Reflections on Myth, Symbol, and Story (1989)

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.