New Dawn Special Issue Vol 8 No 3

“The East has said that when the Banner of Shambhala encircles the world, verily the New Dawn will follow.”

– Nicholas Roerich

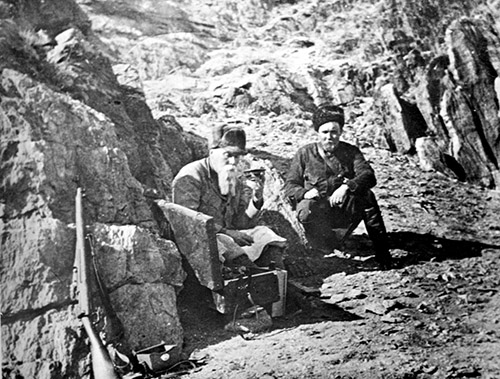

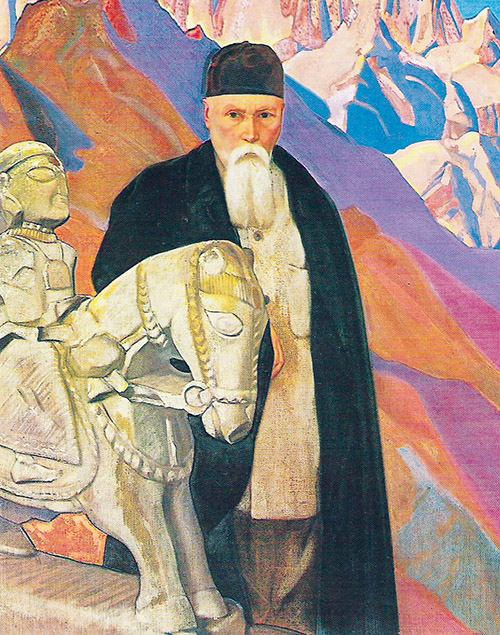

Late in the summer of 1934, a peculiar sage-looking European appeared in Manchuria and then proceeded to Chinese Mongolia. Plump with a round face and a short neatly trimmed beard, this strange man moved around like a high dignitary and spoke English with a heavy Slavic accent. He announced to local officials that he was on a special mission sent by the United States Department of Agriculture to collect drought-resistant plants. Yet, the behaviour of this “botanist” (who in reality was a painter) raised the eyebrows of Japanese intelligence – the entire north-eastern portion of China was occupied by Japan in 1931.

The head of the botanical expedition was not so interested in herbs. Rather he became involved in exploring the political situation and in studying local religious prophecies. He was especially concerned with a Buddhist prophecy called Shambhala. Very popular in the Mongol-Tibetan world, Shambhala was viewed as a legendary land of spiritual bliss – a Tibetan Buddhist paradise – that the faithful believed would arrive after a world-wide battle between the forces of light, the proponents of the “true” Buddhist faith, and the forces of darkness (lalo), the people of alien beliefs. The legend, which emerged in the early Middle Ages when Buddhists had to fight Muslim advances into northern India, eventually became a potent spiritual force in the Tibetan-Mongol world. The name of the man who tried to step into the world of this prophecy was Nicholas Roerich, a Russian émigré painter from New York City. The person who commissioned him to embark on this strange expedition was Henry Wallace, then President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s secretary of agriculture and subsequently his vice president.

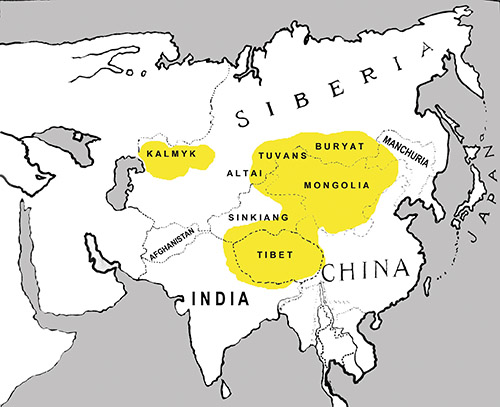

Recent research into this and Roerich’s other Asian ventures in the 1920s and the 1930s1uncovered that his ultimate plan was to establish what he called the Sacred Union of the East, uniting the people of the Mongol-Tibetan world and Siberia. Shambhala and related Inner Asia prophecies would be used to rally the people in all these areas. Roerich contemplated the Sacred Union of the East as an ideal state with cooperatives as its economic foundation and with a universal religion based on reformed Tibetan Buddhism and his version of Theosophy. In his correspondence and in the circle of his acolytes this project was also referred to as ‘Kansas’, the ‘New Country’, or simply as the ‘Great Plan’.

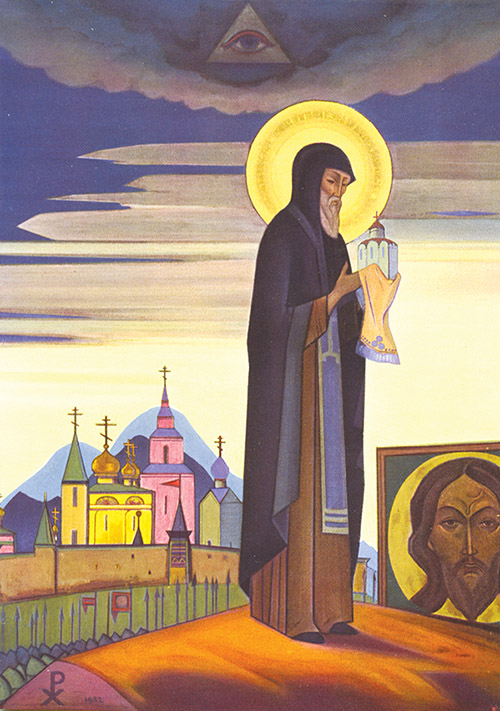

It appears the Shambhala prophecy caught Roerich’s attention as early as 1909 when a group of Tibetan Buddhists living in Russia and headed by Agvan Dorzhiev, a Buryat Buddhist monk and the envoy of the Dalai Lama to the Russian court, received Tsar Nicholas II’s blessing to erect a Tibetan Buddhist Kalachakra temple in St Petersburg. Roerich, who helped to design stained glasses for the temple, became fascinated with Dorzhiev’s stories about Shambhala. No less captivating was the Buryat lama’s dream of bringing all Tibetan Buddhist people together in a united state under the protection of the Russian tsar, whom Dorzhiev declared a reincarnation of the Shambhala king.2 The knowledge received from the learned lama sank deeply in Roerich’s mind, and the painter eventually came to the conclusion that, along with his wife Helena, he was destined to bring the knowledge of the legendary kingdom to humankind.

Simultaneously, Nicholas and Helena Roerich read Helena Blavatsky’s works, frequented occult and Spiritualist salons, and finally set up their own offshoot of Theosophy – Agni Yoga (Fire Yoga). A year before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, they left Russia for Europe and eventually settled in the United States, where they acquired a number of loyal followers. By the early 1920s Nicholas and Helena came to believe that the Great White Brotherhood, the hidden masters of Shambhala, acting through their virtual teacher Master Morya, chose them to speed up human spiritual evolution by establishing a great Buddhist theocracy in the heart of Asia.3

Between 1924 and 1928, they had already made a first abortive attempt to use the Shambhala prophecy to jump-start the Sacred Union of the East by trying to penetrate Tibet and dislodge the 13th Dalai Lama by using the conflict between His Holiness and the Panchen Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet. In pursuit of their goal of the Sacred Union of the East, they attempted to solicit the support of Red Russia, which at that time was interested in spreading the gospel of communism to Asia. Nicholas and Helena journeyed to Moscow, where they met several Bolshevik dignitaries, including foreign intelligence chief Meer Trilisser, and commissar for foreign affairs, Georgy Chicherin, who promised some logistic support to the Roerich’s expedition in exchange for gathering information about Tibet. But they refused to give direct back-up.4 Despite this, with a group of friends and relatives, Roerich boldly ventured to Tibet, where he was blocked by the Dalai Lama and a local British spy master, Colonel Frederick Bailey. Bailey was worried about the throngs of Red pilgrims pouring into the forbidden kingdom from Red Mongolia. Roerich, whose expedition was held up for several months in freezing mountain weather, promptly denounced the Lhasa ruler as the “Yellow Pope” who betrayed the noble truth of original Buddhism and indulged instead into dark shamanic superstitions.5

Cultivating Henry Wallace

The stubborn Roerichs did not give up. From their headquarters in New York City, they continued searching for a powerful sponsor. In fact, they already had one named Louis Horch, a currency speculator, who agreed to throw his money into Roerich’s projects. Marked by a horrible facial trauma, this man and his wife were in a deep emotional crisis and found spiritual comfort in the Roerich circle. The Roerichs tried to acquire political back up, befriending senators, congressmen, and governmental officials. Their biggest coup was making friends with Henry Wallace, a rising politician from Iowa, the secretary of agriculture and later vice president in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.6 Wallace entered the political spotlight during the Great Depression. Like many on the FDR team, the Iowa politician was disgusted with the free market. Yet unlike his comrades, Wallace looked beyond social and economic change, contemplating a spiritual transformation of mankind. A deeply spiritual man, he attributed many social evils to the materialism of Western civilisation. Thus, he joined the growing tribe of Europeans and Americans who searched for redemption in Native American, Oriental, and Western esoteric traditions.

This quest drew him to Indian shamans and Theosophy, and led him to explore cosmic influences on Iowa cereal crops. In the early 1930s, Wallace was still looking for his spiritual niche. Dmitri Borodin, a plant physiologist from Columbia University, who acted as Roerich’s liaison with the Bolsheviks,7helped the seeker find the ‘correct’ path. Sharing with Wallace a common interest in drought-resistant plants, this shady character with possible links to Red Russia’s intelligence services had courted the future secretary of agriculture since the end of the 1920s. Having learned about Wallace’s spiritual side, Borodin revealed that in New York City there lived a man who would be able to quench his spiritual thirst. Thus, Wallace was drawn into Roerich’s circle.

Nicholas Roerich immediately saw that Henry Wallace could be very useful for his plan and began gently cultivating this valuable contact. Massaging Wallace’s ego, Roerich prophesised that the Iowan was destined to become the next US president. Soon Wallace was admitted into the inner circle, receiving a ring and the esoteric name ‘Galahad’ – a reference to the legendary hero who, along with Parsifal, took the Holy Grail to the Orient. Fascinated with Roerich’s stories about travels to Buddhist areas, Wallace withdrew from the mainstream Theosophical Society and took up the Roerichs’ cause. Through Wallace, Nicholas and Helena were able to reach out to US President Roosevelt, who already knew about the painter through his mother Sara, a woman with occult leanings.

Soon Helena corresponded directly with the president, sending FDR her “fiery messages” peppered with advice about domestic and international politics. In February 1935, she finally felt comfortable enough to reveal to the chief executive the details of the Great Plan, hinting that the United States might help this noble project: “Thus, the time for reconstruction in the East has come, and let us have friends of the Orient in America. The Union of Asian peoples is envisioned. The unification of the tribes and nationalities will proceed gradually. They will have their own federation. Mongolia, China, and the Kalmyk will counterbalance Japan. Mr. President, in this project of unification we need your good will.”8

“Now we have reached the future!”

Meanwhile, rubbing shoulders with Wallace, Roerich suddenly saw an opportunity to use this friendship for his occult geopolitics. In the wake of the horrible drought that hit America’s Central Plains, the US Department of Agriculture started looking for drought-resistant grasses and cereals, sending out its people to various parts of the globe, including Central and Inner Asia. When Roerich discovered this, he was quick to offer himself as an expert on Asian plant life. According to the painter’s occult calendar, it was a good time for him to step out of the shadows and attempt to launch again the Sacred Union of the East. On 17 December 1933, the 13th Dalai Lama died. To his circle of the elect, Roerich announced, “Now we have reached the future!”9

By the end of December, Wallace was already in Roosevelt’s office, trying to sell his boss on the idea of an Asian botanical expedition that would include Roerich and his son George. The president, who took a personal interest in Roerich’s cause, liked the project and gave permission to proceed. At the same time, Wallace indirectly tried to prepare FDR for something bigger than simply a botanical venture, vaguely hinting that the political situation in Asia was always quite intriguing because of various ancient prophecies and legends. Yet, instead of going to Tibet and Western China, the areas that earlier were so dear to Roerich’s heart, the painter now rushed to north-eastern China: Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. Why such a sudden change of itinerary?

Although the death of the Dalai Lama was surely an important occult sign, bringing instability to Lhasa, Tibet was not in revolt. In contrast, Manchuria, Chinese (Inner) Mongolia, and Red Mongolia were all on fire. In 1931, Japan, a rising imperialist giant, suddenly invaded China and occupied her north-eastern part (Manchuria). From there, imperial Japan now threatened the Soviet Far East, Mongolia, and Central China. During the same year, Mongol shepherds and lamas revolted against communism and linked their hopes to the advancing Japanese troops, which they viewed as the army of legendary Shambhala that would deliver them from Russian and Chinese oppressors.10

This was the explosive situation Roerich craved to step into. It was time to set in motion his great plan. With fire in his eyes, the painter exclaimed, “Imagine, suddenly an invincible Mongolian army shows up and begins to win and to act – amazing!”11

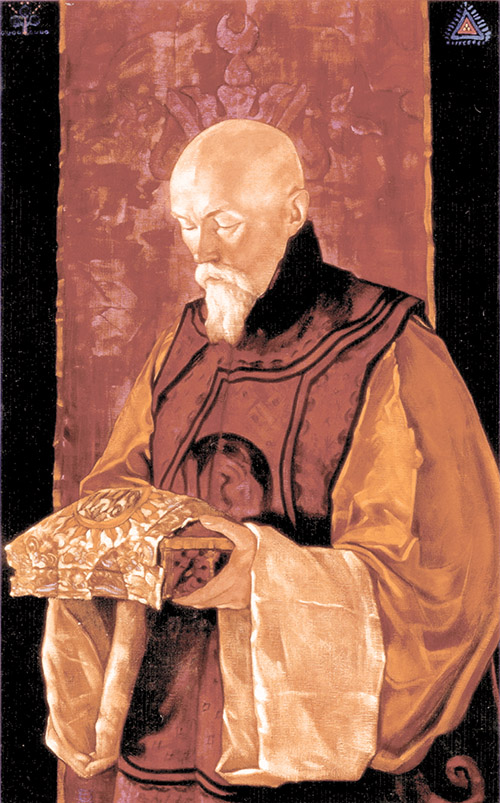

Moreover, Roerich imagined himself as the head of the future Shambhala army. On one of his canvases he portrayed himself as St. Sergius, an Orthodox military patron saint, with Mongol features surrounded by an army of warriors with spears ready for an attack. Helena fed her husband’s geopolitical ambitions by constantly declaring that theirs was a time for assertive politicians. She pointed out that all over Asia, Europe, and even in the United States, people were opting for strong-willed leaders.

Yet, troubles pursued the Shambhala warrior from the very beginning. In August 1934, on their way to Manchuria, the painter and his son stopped in Japan. There, without any official credentials, Nicholas began to act as a high American dignitary, meeting the Japanese secretary of war and praising him for the job the Japanese occupation army was doing in China. Three years earlier, the United States had condemned Japan for invading China, and Roerich’s behaviour now looked very embarrassing.

As soon as the “botanical expedition” stepped on Chinese soil, George Roerich got in touch with a representative of the Panchen Lama. But, surrounded by a tight ring of intelligence agents from various countries, the spiritual leader of Tibet exercised extreme caution and refused to get involved in any grand scheme. Accompanied by several armed guards recruited from the ranks of Russian émigrés, the Roerichs then made a blitz visit to the Manchurian Mongols, mingling with local princes and lamas. From Manchuria, Roerich and his son drove to Inner Mongolia, where they met Teh Wang, leader of the Mongol national liberation movement against the Chinese, promising him American support – another reckless step that further raised the eyebrows of US diplomats in China and Japan.

En route, George kept a detailed diary, which resembles more of a military journal than travel notes. He carefully scanned the topography of places they visited, measured hills and distances between various sites and towns, noted major intersections, and provided detailed information about the Japanese military transportation system. In short, this was a blueprint for developing future defensive and offensive plans.12

Who was to benefit from this intelligence? Roerich with his Sacred Union of the East project or somebody else as well?

Smears & Intrigues Beset Roerich

Concerned about Roerich’s suspicious movements, Japanese intelligence unleashed a smear campaign against him in the press. The press wrote that Roerich was a Freemason, which was not true, who sought to establish a great Siberian state – which did contain elements of truth. Several newspapers drew attention to his brief romance with the Bolsheviks in 1926, wondering if it was still going on. Meanwhile, the American press raised hell, speculating about some hidden US government agenda linked to the Roerich Manchurian expedition. The painter was caught in the crossfire of diplomatic, espionage, and media games.

Still worse, the US State Department informed Roerich’s patron Wallace that the Soviets had sent a confidential protest to the American government, complaining that the dangerous émigré Roerich was wandering along the borders of Red Mongolia. The Bolsheviks were worried that “the armed party is now making their way toward the Soviet Union ostensibly as a scientific expedition but actually to rally former White elements and discontented Mongols.”13To the last moment, Wallace backed up Roerich and dismissed all insinuations against his “botanist.” Only when he realised the painter was a diplomatic embarrassment and that his own career was now on the line did the secretary of agriculture call off the expedition, cutting funding and terminating all his contacts with his former guru. Eventually, along with Louis Horch, another sponsor who dropped Roerich, Wallace turned against the painter, initiating a tax-evasion lawsuit against him and seizing his properties in the United States. FDR, embarrassed by the whole situation, personally intervened, promising Horch and Wallace to call the judge who handled the case in order to guarantee the “correct” verdict. Sure enough, Roerich, who trusted Horch to handle his finances, was indicted. Betrayed and humiliated by his partners, Roerich never returned to the United States, wisely choosing to settle in India.

Red Russia & Boris Roerich

What went unnoticed at the time was that in January 1933 in Leningrad, right on the eve of the Manchurian expedition, Boris Roerich, a brother of the painter who remained in Red Russia, was suddenly released by the Bolshevik secret police (OGPU). In May 1931, the secret police had set up and then arrested Boris. There is an interesting twist here. Boris’ two-year sentence seems more a house arrest. An architect by profession, he was confined to work at the secret technical bureau, designing the Big House, which headquartered the Leningrad branch of the secret police. Here Nicholas Roerich’s brother worked under Nikolai Lansere, the Soviet architectural star who received a similar sentence.14

From Boris’ recently declassified secret police file, it is clear that OGPU was using him as a tool in some sophisticated game that most certainly involved Nicholas Roerich. As early as February 1929, the secret police searched Boris’ apartment, trying to find materials that might implicate him in espionage. Two months later, he was recruited by OGPU and began working as a secret informer. Yet, as mentioned above, two years later, OGPU suddenly framed and arrested him for smuggling, sentencing him to three years in a concentration camp. However, hardly had two months passed before this draconian sentence was miraculously waived and replaced by benevolent confinement in the golden cage of the secret technical bureau.15 But this strange story does not end here. From 1936 to 1937, now in Moscow and again with Lansere, Boris Roerich began working on the monumental project of the All-Union Institute of Experimental Medicine (VIEM), a notorious “new age” Stalinist research centre. What followed was even more stunning. From 1937 to 1939, during the period of The Great Purge, Boris continued his career as if nothing happened and even improved his material conditions by moving from Leningrad to an elite neighbourhood in Moscow, where he quietly died a natural death in 1945.16

The facts of Boris Roerich’s biography are revealing. Even without having such a “dangerous” brother, Boris, simply as a former White officer who fought against the Bolsheviks during the Civil War, was a prime candidate if not for execution then at least for a twenty-five-year sentence in a concentration camp. Still, by some providential force, the Bolsheviks’ vengeance never reached him. How to explain this miracle? What was the magic shield that protected Boris Roerich? The most obvious answer is that this magic guardian was his adventurous brother. Remembering that the use of relatives to guarantee the cooperation of victims and the loyalty of OGPU agents was standard practice for Stalin’s secret police, all pieces of the puzzle fall in place.

It is quite possible that Boris was a bargaining chip in some devious and sophisticated spy game that involved Nicholas Roerich. I will not repeat here the far-fetched argument made by Moscow writer Oleg Shishkin17 that after 1919 or 1920 the painter was always a paid Bolshevik spy and that his Master School in New York City at 310 Riverside Drive was a cover for a Soviet spy ring. There is simply no credible evidence to support such a statement. At the same time, one cannot totally exclude the possibility that at some point Roerich was simply blackmailed by the Soviet secret police and forced to perform occasional clandestine assignments, especially during his Manchurian venture. These assignments might not have necessarily contradicted his Sacred Union of the East project. They could include monitoring Japanese military activities near Red Mongolia’s border, the location of their troops and military hardware, the status of Manchuria as a puppet state, and the general geopolitical situation in the area, a major concern for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Bolshevik intelligence threw a tremendous amount of resources and workers into the Far East, recruiting hundreds of unemployed White émigrés to spy on the Japanese. Besides, restraining the possible Soviet agent of influence who worked to unite White Russians and Mongols in a sacred crusade against communism was not a bad idea. Viewed from this angle, the protest quietly delivered by the Soviets to the United States in 1935 regarding Roerich’s “armed and dangerous party” might have simply been a good smokescreen to smooth the mission of the reluctant agent. As long as Boris remained in the hands of the Soviet secret police, the painter’s cooperation could be safely solicited anytime.

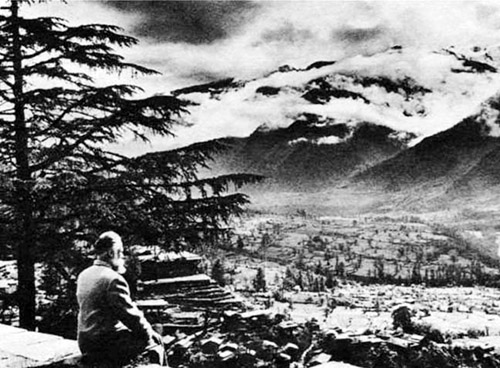

After his second attempt to launch the Sacred Union of the East from Manchuria failed and after Horch seized his Master Building in New York City, Nicholas and Helena along with their two sons settled in India in the picturesque Kulu Valley, right next door to Tibet. Immersing himself in painting local landscapes and entertaining occasional visitors, Roerich finally laid to rest his grand dream. In Kulu, the painter peacefully died in 1947 from prostate cancer. His wife followed him eight years later.

Before he died, during the Second World War when Nazi Germany attacked Russia, Roerich suddenly became openly pro-Soviet and patriotic. Moreover, after the war ended, he approached the Soviet government, asking permission to return to Russia. Did the old man expect some special treatment from Stalin for occasional services he might have provided to the Bolshevik regime? Or was he simply an old, naïve idealist who felt nostalgia for his motherland? Who knows? Fortunately for him, Red Russia refused to issue such permission. Roerich, who did not know anything about real life in the Bolshevik utopia, was certainly unaware how lucky he was. What could await him in Stalinist Russia in case he returned? The atmosphere of total suspicion, suffocating propaganda, and possibly a prison sentence more likely.

In 1957, after the death of Stalin, following in his father’s footsteps, George Roerich, a linguist and Tibetan scholar who was always part of his parents’ Sacred Union of the East project, asked and did receive permission to immigrate to the Soviet Union. The Soviets not only let him in but also awarded him a prestigious job as a senior research fellow at the Moscow Institute of Oriental Studies. Three years later he died from natural causes. The younger son, Svetoslav, an architect, lived a long life and died in 1993 at his estate in Bangalore, India.

For a detailed examination of the subjects discussed in the above article, read Andrei Znamenski’s 2012 book Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy, and Geopolitics in the Heart of Asia.

Footnotes

1. The two-volume biography of Roerich by Rosov (2002, 2004) is the most comprehensive and complete account of his life: Rosov, Vladimir. Nikolai Rerikh vestnik Zvenigoroda [Nicholas Roerich: Messenger of Zvenigorod], vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Aleteiia, 2002; Rosov, Vladimir. Nikolai Rerikh vestnik Zvenigoroda [Nicholas Roerich: Messenger of Zvenigorod], vol. 2. Moscow: Ariavarta-Press, 2004, 79-80; also Andreev, Alexandre, Gimalaiskoe bratstvo: teosofskii mif i ego tvortsy [Himalayan Brotherhood: Theosophical Myth and its Creators]. St. Petersburg: iz-vo St. Petersburgskogo universiteta, 2008. For a good general overview of Roerich’s activities, see: McCannon, John. “By the Shores of White Waters: The Altai and Its Place in the Spiritual Geopolitics of Nicholas Roerich,” Sibirica: Journal of Siberian Studies 2, no. 3 (2002): 166–89; Spence, Richard. “Red Star over Shambhala: Soviet, British and American Intelligence & the Search for Lost Civilization in Central Asia,” New Dawn 109, July-August (2008); Osterrieder, Markus. “From Synarchy to Shambhala: The Role of Political Occultism and Social Messianism in the Activities of Nicholas Roerich,” in The New Age of Russia: Occult and Esoteric Dimensions, eds. Birgit Menzel, Michael Hagemeister, Bernice Rosenthal. Munchen and Berlin: Kuban & Sagner, 2011.

2. Meyer, Karl Ernest and Shareen Blair Brysac. Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. New York: Basic Books, 2006, 454.

3. Roerich, Nicholas. Shambhala. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1930, 11; Roerich, Helena, Vysokii put’ [High Path], vol. 1 (1920–1928). Moscow: Sfera, 2006, 45, 51, 65.

4. Fosdick, Zinaida. Moi uchitelia: vstrechi s Rerikhami (po stranitsam dnevnika, 1922–1934) [My Teachers: Meetings with the Roeriches (Pages from the 1922-1934 Journal)]. Moscow: Sfera, 1998, 206 265; Brachev, Viktor. Okkultisty sovetskoi epokhi [Occultists of the Soviet Age]. Moscow: Bystrov, 2007, 234-35; Rosov, Vladimir. Nikolai Rerikh vestnik Zvenigoroda [Nicholas Roerich: Messenger of Zvenigorod], vol. 1. St. Petersburg: Aleteiia, 2002, 180.

5. Roerich, 1930, 5, 47, 61.

6. For more about relationships between Roerich and Wallace, see Meyer and Brysac 1999: 474–91;Williams, Robert C. Russian Art and American Money, 1900–1940 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980, 136-43;Culver, John C. and John Hyde. American Dreamer: The Life and Times of Henry A. Wallace. New York: Norton, 2000.

7. Fosdick, 1998, 242.

8. Roerich, Helena, Pis’ma [Letters], vol. 3. Moscow; MTR, 2001, 351.

9. Fosdick, 1998, 609.

10. Bowden, C.R. Modern History of Mongolia. New York: Praeger, 1968, 205.

11. Fosdick, 1998, 659.

12. Rosov, 2004, 79-80.

13. Meyer, Karl Ernest and Shareen Blair Brysac, 2006, 488.

14. Rosov, Vladimir. “Arkhitekhtor B. K. Rerikh: Rassekrechennoe arkhivnoe delo N. 2538 [Architectural Designer B. K. Roerich: Declassified File No. 2538],” Vestnik Ariavarty [Messenger of Aryavarta] 10 2008, 43.

15. Rosov, 2008, 46.

16. Yudin, Andrei. Tainy Bol’shogo doma [Secrets of the Big House]. Moscow: Astrel, 2007, 15.

17. Shishkin, Oleg. Bitva za Gimalaii: NKVD, magiia i shpionazh [Fight for the Himalayas: NKVD, Magic, and Espionage]. Moskva: Olma-Press, 1999, 27-40, 51-63, 72-75, 105-123.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.