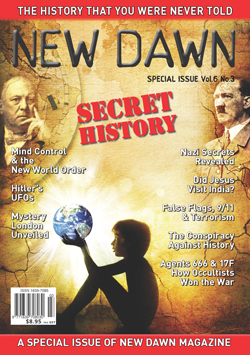

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 6 No 3 (Aug 2012)

There is no proletarian, not even communist movement, that has not operated in the interests of money, in the directions indicated by money, and for the time permitted by money – and that without the idealist amongst its leaders having the slightest suspicion of the fact.

– Oswald Spengler1

One of the great myths of history is the concept of the mass people’s revolt against tyranny, epitomised in our era by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. Much political analyses have focused on the supposed clash between socialism and capitalism. The philosopher-historian Oswald Spengler was one of the first in our era to point out that revolts in the name of ‘the people’ operate in the service of the moneyed class:

Herein lies the secret of why all radical (i.e. poor) parties necessarily become the tools of the money-powers, the Equites, the Bourse. Theoretically their enemy is capital, but practically they attack, not the Bourse, but Tradition on behalf of the Bourse. This is as true today as it was for the Gracchan age, and in all countries…2

The concepts of Liberalism and Socialism are set in effective motion only by money. It was the Equites, the big-money party, which made Tiberius Gracchu’s popular movement possible at all; and as soon as that part of the reforms that was advantageous to themselves had been successfully legalised, they withdrew and the movement collapsed.3

The socialist triumphs, whether by revolt or by the ballot box, have generally been no more directed by ‘the people’ than the present so-called ‘Arab Spring’, or the sundry ‘velvet revolutions’ funded and prompted by George Soros’ Open Society Institute, the US State Department, National Endowment for Democracy, Freedom House, and sundry other plutocratic think tanks.4

Russia Targeted

New York financial interests marked Russia for revolt at least a dozen years before the Revolution. It was first necessary to sour the hitherto friendly relations existing between Americans and Russians, by portraying the Czar as the pinnacle of antiquated tyranny. A journalist, George Kennan, was chosen for the purpose. Historian Thomas A. Bailey stated of Kennan that “no person did more” to turn Americans against the Czar.5

The opportunity for undermining Czarism came with the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. During this time Kennan was in Japan organising Russian POWs into “revolutionary cells,” and claimed to have converted “52,000 Russian soldiers into ‘revolutionists’.” Cowley comments that such activities were “well-financed by groups in the United States.”6 The financial patron was primarily Jacob Schiff, senior partner of Kuhn, Loeb & Co, New York.

World War I provided the opportunity to deal a deathblow to the Czar, serving as a catalyst for the March 1917 Revolution. Kennan reported of a celebratory event in New York by the “Friends of Russian Freedom,” that the dissemination of revolutionary propaganda among Russian soldiers in 1905, who formed the cadres of the 1917 Revolution, had been “financed by a New York banker you all know and love,” Jacob Schiff. The New York Times reported that a telegram was read from Schiff to the gathering referring to “what we had hoped and striven for these long years.”7

Writing to The Evening Post in response to a question about revolutionary Russia’s new status on the world financial markets, Schiff stated:

Replying to your request for my opinion of the effects of the revolution upon Russia’s finances, I am quite convinced that with the certainty of the development of the country’s enormous resources, which, with the shackles removed from a great people, will follow present events, Russia will before long rank financially amongst the most favoured nations in the money markets of the world.8

This reflected the generally jubilant attitude of the international financiers. John B. Young of the National City Bank, who had been in Russia in 1916 in regard to a US loan, stated of the revolution that it was discussed widely when he had been there. He regarded those involved as “solid, responsible and conservative.”9 In the same issue of The New York Times it was reported there had been a rise in Russian exchange transactions in London 24 hours preceding the revolution, and that London had known of the revolution prior to New York. The article reported that most prominent financial and business leaders in London and New York had a positive view of the revolution.10 Another report states that while there had been some disquiet about the revolution, “this news was by no means unwelcome in more important banking circles.”11

‘The Bolshevik of Wall Street’

The March Revolution was the prelude to the November Bolshevik Revolution. Again, international financial interests were involved from the start. This was primarily undertaken under the guise of the American Red Cross Mission to Russia, which comprised mostly Wall Street rather than medical personnel.12 The Mission was under the direction of William Boyce Thompson, a director of the NY Federal Reserve Bank, who funded the Mission along with International Harvester. According to Thompson’s assistant, Cornelius Kelleher, the mission was “nothing but a mask” for business interests.13

Such was Thompson’s enthusiasm for Bolshevism that he was nicknamed “the Bolshevik of Wall Street” by his business comrades. Thompson gave an interview with The New York Times shortly after his four-month tour with the American Red Cross Mission, expressing his favourable views on the still precarious Bolshevik regime. The article states that Thompson’s “opinion is that Russia needs America, that America must stand by Russia.” He stated: “The Bolsheviki peace aims are the same as those of the Untied States.” The Times commented:

Colonel Thompson is a banker and a capitalist, and he has large manufacturing interests. He is not a sentimentalist nor a ‘radical’. But he has come back from his official visit to Russia in absolute sympathy with the Russian democracy as represented by the Bolsheviki at present.14

Thompson stated that in reply to surprise at his pro-Bolshevik sentiments he did not mind being called “red” if that meant sympathy for 170,000,000 people “struggling for liberty and fair living.” He said that “the present government in Russia is a government of workingmen. It is a Government by the majority, and, because our Government is a government of the majority, I don’t see how we can fail to support the Government of Russia.”15

Trotsky’s Business Connections

While the manner by which Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin and his entourage made their way by train to Russia courtesy of the German General Staff, facilitated by the wealthy and well-connected Marxist ‘Parvus’ (Israel Helphand), is well documented,16 the manner by which Leon Trotsky reached Russia from New York has been obscure.

Dr. Richard Spence of Idaho State University has provided the best research. While Lenin and Co. were backed by German interests, Spence provides convincing evidence that the British were backing Trotsky. However, behind both stood international financiers, centred on Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in Wall Street, and the Warburg banking dynasty, which encompassed simultaneously Allied and German business. In the centre of these interests around Trotsky was Sir William Wiseman,17 de facto head of the British Secret Service in the USA who, interestingly, stayed in America after the war to work with Kuhn, Loeb & Co. becoming a partner in 1929.

When Trotsky arrived in New York with his family, despite later claims that he was “penniless,” he carried at least $500 (the equivalent of $10,000 today) and had been booked into the elite Hotel Astor. After a brief stay, the Trotsky’s were provided with a spacious apartment in the Bronx, and were taken under wing by Dr. Julius Hammer, who lived nearby.18 Like Parvus, Dr. Hammer was another example of a millionaire Marxist, whose son Armand, as head of Occidental Petroleum, became a mainstay of commercial relations with the USSR for decades,19 interrupted only by the Stalinist interregnum.20

Spence further traces associations between the enigmatic British master spy Sidney Reilly, whose dealings seem to have been duplicitous, having traded with the Germans as a director of Allied Machinery Co. He was associated in business with Abram Zhivotovskii, an international banker who was Trotsky’s maternal uncle.21 Zhivotovskii in turn was associated with Olof Aschberg,22 head of the Nye Banken, Stockholm, who channelled funds to the Bolsheviks, earning Aschberg the title of “Bolshevik banker.” Uncle Abram, suspected of being a German agent while supposedly working for the Russian Government, was described by the US State Department as laundering large sums to the Bolsheviks, while professing to be anti-Bolshevik.23

As for Aschberg, Dr. Antony Sutton of the Hoover Institution cites a US State Department File Green Cipher message from the US Embassy in Christiania (Oslo), dated 21 February 1918, stating that Bolshevik funds were deposited in the Nye Banken.24 When the Bolsheviks established their international bank Ruskombank in 1922, it was headed by Aschberg, with Max May, vice president of the JP Morgan bank Guaranty Trust Co., as director of the Foreign Division.25

However, to return to Trotsky, when the call came to get back to Russia, en route he was detained at Nova Scotia, Canada by British authorities, on suspicion of being a German agent.26 Spence points out that Trotsky was just the type of revolutionary that Wiseman would seek out to direct the movement. Spence believes that Trotsky’s brief detention at Nova Scotia on suspicion of pro-German sympathies would make sense as a pretext for allaying suspicions as to a pro-British agenda. He was soon allowed to proceed.

Pro-Bolshevik Agendas

The Bolsheviks took several years of a very bloody civil war to consolidate their hold over Russia. Their initial position did not extend much beyond Moscow and Petrograd (now St Petersburg). Both socialist and mainstream Western history maintain the Bolsheviks were engaged in a life and death struggle with reactionaries who received largesse from the capitalist powers. As will be seen below, this is not correct. However, diplomatically, plutocratic interests lost no time in advocating for the Bolshevik cause in the aftermath of World War I. We have already considered the actions of William Boyce Thompson and the merchant interests that comprised the bulk of the Red Cross Mission to Russia. There was also high-powered lobbying behind the scenes at the peace conferences.

Two prominent sources, one conservative, and one socialist, observed the same machinations of High Finance on behalf of Bolshevism. Henry Wickham Steed, editor of The London Times, with the backing of the newspaper’s proprietor, Lord Northcliffe, was a one-man lobby against the powerful international forces trying to secure support for Bolshevik Russia. The extent of his success was due to his position in being able to publicly expose these machinations while also publicising the atrocities of the Bolsheviks.

In a first-hand account of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Wickham Steed stated that proceedings were interrupted by the return from Moscow of William C. Bullitt and Lincoln Steffens, who had been sent to Russia by Colonel Edward M. House27 and US Secretary of State Robert Lansing, to study political and economic conditions and report back to the US Commissioners plenipotentiary at the peace conference. Steed observed that Jacob Schiff was particularly “eager to secure recognition” of the Bolsheviks, also writing that, “Potent international financial interests were at work in favour of the immediate recognition of the Bolshevists.”28 House met Steed and expressed concern at the publicity Steed was giving to the machinations. Steed replied that it was Schiff, Warburg and other bankers who were behind the diplomatic moves in favour of the Bolsheviks in order to secure the exploitation of Russia. I have written on this subject that:

House disingenuously asked Wickham Steed to compromise; to support a move that would supposedly secure benefits for both the pro-Bolshevik and non-Bolshevik Russian masses in terms of humanitarian aid. Wickham Steed agreed to consider this, but soon after talking to House found out that British Prime Minister Lloyd George and Wilson were to proceed with recognition the following day. Steed therefore wrote the leading article for the Paris Daily Mail of March 28th, exposing the manoeuvres and asking where a pro-Bolshevik stance stood with Wilson’s high moral principles for the post-war world?29

Steed was visited again by House, who stated that Steed’s article in the Paris Daily Mail, “had got under the President’s hide”; while the publicity also bothered Prime Minister Lloyd George as it was preventing him from recognising the Bolsheviks.

Several years later, on the other side geographically and politically, Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, also observed that it was capitalistic interests that were lobbying for the Bolsheviks. On 1 May 1922 The New York Times reported that Gompers, reacting to negotiations at the international economic conference at Genoa, declared that a group of “predatory international financiers” were working for the recognition of the Bolshevik regime for the opening up of resources for exploitation. He also noted that prominent Americans who had a history of anti-labour attitudes were advocating recognition of the Bolshevik regime.30

The American ‘Intervention’

If capitalistic interests were really supporting the Bolsheviks, the sceptical reader might ask, what is one to make of the Allied ‘intervention’ on the side of the White Armies against the Red Army during the Russian Civil War? Again we are faced with the simplifications and obfuscations of socialist propaganda and Western mainstream academia. The Allies sent troops into Russia when there was an impending collapse of the Russian Home Front, for the purpose of ensuring that Allied war supplies sent to Russia would not fall into German hands. While there were those in military, diplomatic and political circles that did want to assist the White Army and fight the Bolsheviks, these never prevailed. Many others of much greater influence sought a policy that was a literal ‘stab in the back’ to the forces fighting the Red Army.

US State Department Russia expert George F. Kennan31 stated that when the Americans sent their first representative to Archangel in 1917, at the time the Bolsheviks had seized power, Archangel was an important strategic port where war supplies that had been shipped by the Allies had accumulated in large quantities.32 This materiel included 2,000 tons of aluminium, 2,100 tons of antimony, 14,000 tons of copper, and 5,230 tons of lead, etc.33 With the possibility of Russia concluding an armistice with Germany, the Allies were anxious to recover the stocks. The Bolsheviks dispatched a commission to Archangel to deliver the war materials to the interior.34 Despite the arrival of two British ships, the British sat by for several months while the Bolsheviks removed the war materiels.35 The second factor was to ensure the safety of Czech soldiers who had been prisoners-of-war in Russia and wished to fight Germany with the aim of gaining support for Czech nationhood after the war. Their release was agreed by the Bolshevik regime and the Americans and Japanese were responsible for their transport by rail to Vladivostok.36

The attitude of the Bolsheviks in regard to armistice with Germany was far from clear. Trotsky in particular did not support Lenin’s priority to withdraw from war, and after aggravating the German representatives at Brest-Livotsk, resigned as Commissar for Foreign Affairs, assuming the position of Commissar for Military Affairs and head of the Red Army. This resulted in the Germans launching another offensive on the Eastern Front against the embryonic Red Army. This caused a sense of “solidarity” between the Allies and the Bolsheviks.37 Trotsky remained a focus of efforts to secure Bolshevik support for the Allied war effort. There is no sense, therefore, in the perception that the Allies invaded Russia to destroy Bolshevism.

The resistance to Bolshevism formed around Admiral A.V. Kolchak, who created the White Army and established control over Siberia, while other White forces were pressing against the only two Bolshevik strongholds, Petrograd and Moscow. Kolchak was pro-British by inclination, but if not given any choice would be obliged to turn to the Germans for assistance. The USA therefore established a military presence in Siberia under the command of Major-General Robert Graves, whose hatred of the opponents of Bolshevism, and of Kolchak in particular, ensured Kolchak’s defeat and death. While Gajda, head of the Czech soldiers, and British General Knox tried to pursue an anti-Bolshevik position, Graves told Gajda that “as long as he was in command no American soldiers would be used against the Bolsheviks.”38 Graves’ real policy, however, was far from neutral: he pursued a pro-Bolshevik agenda wherever he was able. To what level this antagonism descended can be seen by the situation with the American Red Cross, which Graves slandered as having “no sympathy for the aspirations of the Russian people.” When the Red Cross was found to be providing Kolchak’s forces with warm underwear and running hospitals for the troops, Graves responded that no further guards would be available for Red Cross trains unless this humanitarian aid ceased.39

In March 1919 Captain Montgomery Schuyler, Chief of Staff of the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, reporting from Omsk to Lt. Colonel Barrows in Vladivostok, wrote of his misgivings, stating that, “It is very largely our fault that Bolshevism has spread as it has and I do not believe we will be found guiltless…”40

By late 1919 the Kolchak forces were in retreat, and the White offensive was beginning to be crushed throughout Russia. The White Army had never received training and weaponry from the Allies, and were scuttled by Allied withdrawal. Lack of diplomatic recognition had also been a major factor in undermining the Kolchak Government at Omsk.

The New York Times, reporting on the routing of Kolchak by the Red Army, placed the blame on the Allies, particularly the US Administration. The Admiral’s White Army had been beaten back over 800 miles, “because he had not sufficient gun power, no airplanes, no tanks, and little food.”

The Allies withheld the necessary supplies, especially the supplies of arms and ammunition from the Omsk Government… [T]he Allies have given no officers to Kolchak, not even a non-commissioned officer to train the undisciplined privates he has in some fashion dragged together. So Kolchak, without ammunition, food or other supplies, and with a patriotic mob he cannot discipline by himself without aid, has done wonders and has finally been routed…41

In the midst of this Allied scuttle of the White Army, the USA kindly allowed Kolchak to receive the weapons he had paid for several years previously. However, Graves still ensured that even now there were delays and ill-will attached to the late delivery. The New York Times reported on the situation:

Major General Graves recently refused delivery of the arms to the Russian authorities at Vladivostok, his action resulting in criticism of the American command by the Russian authorities in the Far East, as well as by General Knox, chief of the British Military Mission at Omsk, who said that General Graves had held up the delivery of arms which the Russians had bought and paid for.42

In December 1919 a revolt by an army regiment against Kolchak in Irkutsk resulted in the proclamation of a revolutionist Government, whose forces captured the railway station. Kolchak threatened to bomb the station but was prevented from doing so by the Allies, and the station was declared “neutral.” Kolchak drove the revolutionists across the Irkutsk River. However, several days later he was detained at Nijnie Udinsk after the establishment of a revolutionary authority. Several hundred of Cossack Ataman Semenoff’s soldiers arrived and clashed with the revolutionists. On 12 January 1920 American troops clashed with Semenoff’s troops.43 Thus, one of the final acts of the American forces had been to fight against the desperate remnants of the White movement under Semenoff, Kolchak’s successor, as he attempted to assist the Admiral.44

The American forces guarding the Trans-Siberian railway left Vladivostok amidst wild acclaim from the revolutionist regime. The New York Times reported:

Parades, street meetings and speechmaking marked the second day today of the city’s complete liberation from Kolchak’s authority. Red flags fly on every Government building, many business houses and homes. There is a pronounced pro-American feeling evident. In front of the American headquarters the revolutionary leaders mounted steps of buildings across the street, making speeches calling the Americans real friends, who at a critical time saved the present movement.45

In 1920, in the midst of defeat, Kolchak stated that “the meaning and essence of this intervention remains quite obscure to me.”46 Kolchak was captured after being betrayed by his Czech guard and was shot by the Revolutionist regime on 7 February.47

The New York Times editorialised with pertinent analysis of the Allied “intervention” and the impending collapse of the White remnants:

There can be no doubt that the allied Governments must bear a large part of the blame for the collapse of this movement. As The New Europe recently observed, ‘the publicly proclaimed vacillations of our statesmen are worth a whole army corps to the Bolsheviki’.48

Big Business and the Soviets

Big business is by no means antipathetic to Communism. The larger big business grows the more it approximates to Collectivism. It is the upper road of the few instead of the lower road of the masses to Collectivism.

– H.G. Wells

In 1920, when the Allies were in Vladivostok to supposedly assist the Whites, an American businessman, Washington Vanderlip, representing a consortium of US business interests and the US Government, was negotiating a concession with Lenin for what would have virtually made the whole region a protectorate of the USA. This involved a sixty-year lease of the Far Eastern Kamchatka Peninsula to secure important oil and mining concessions.49 Vanderlip embarked on his mission at a time when the Soviets did not control the region, and undertook the trip with the authority of the US State Department.

At the time the ‘ownership’ of Kamchatka was not even known to Lenin, but the Japanese were in possession, and did not withdraw until signing a Treaty with Soviet Russia in 1925. Lenin pointed out that an American presence, including a naval base, would act as a “buffer” to Japanese aggression, stating: “Actually the Japanese are in possession, and they do not relish the idea of our giving it away to the Americans.”50 Hence the statement often made that the Vanderlip concession never became operative because of opposition from the US Government and “big business” is incorrect.51 However, American “big business” had initiated commercial relations with the Bolsheviks as early as 1920, the press reporting that “on the initiative of American businessmen a new international organisation had been formed in Denmark to exchange raw materials for manufactured goods after ‘lengthy discussions with Maxim Litvinoff’, Commissar for Foreign Affairs.”52

It was a chance meeting between Fabian-socialist, pro-Bolshevik historian and novelist H.G. Wells with Washington Vanderlip in Russia that prompted Wells to comment:

The only Power capable of playing this role of eleventh-hour helper to Russia single-handed is the United States of America. That is why I find the adventure of the enterprising and imaginative Mr. Vanderlip very significant. I doubt the conclusiveness of his negotiations; they are probably only the opening phase of a discussion of the Russian problem upon a new basis that may lead it at last to a comprehensive world treatment of this situation. Other Powers than the United States will, in the present phase of world-exhaustion, need to combine before they can be of any effective use to Russia. Big business is by no means antipathetic to Communism. The larger big business grows the more it approximates to Collectivism. It is the upper road of the few instead of the lower road of the masses to Collectivism.53

In 1923 the omnipresent think tank, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR),54 whose luminaries such as Warburg, Schiff and Edward M. House, had been involved in attempting to secure support for the Bolshevik regime when it hardly held Russia, issued its report on the Soviets. As has been seen, however, Big Business had been busy enough in its dealing with the Bolsheviks since 1917. CFR historian Peter Grose, in his semi-official history of the Council, states:

The impetus for this first study was Lenin’s New Economic Policy, which appeared to open the struggling Bolshevik economy to foreign investment. Half the Council’s study group were members drawn from firms that had done business in pre-revolutionary Russia, and the discussions about the Soviet future were intense. The concluding report dismissed “hysterical” fears that the revolution would spill outside Russia’s borders into central Europe or, worse, that the heady new revolutionaries would ally with nationalistic Muslims in the Middle East to evict European imperialism. The Bolsheviks were on their way to “sanity and sound business practices,” the Council study group concluded, but the welcome to foreign concessionaires would likely be short-lived.55

The CFR was correct in warning that the opening up of the USSR to exploitation under Lenin and Trotsky might be short-lived. Four years later Joseph Stalin had consolidated absolute power, and the plutocrat’s favourite, Trotsky, was gone. Armand Hammer, head of Occidental Petroleum, reminisced that he had intimately known every Soviet leader from Lenin to Gorbachev – except for Stalin. In 1921 Armand Hammer was in the USSR concluding business deals when he met Trotsky (whom it should be recalled was a guest of Armand’s father Julius in New York) who wanted to know whether financial circles in the USA “regard Russia as a desirable field of investment?” Trotsky remarked to Hammer that “capital was really safer in Russia than anywhere else” because capitalists who invested there would have their investments protected even after the “world revolution.”56 Hammer states that Trotsky remarked to him that, “no true Marxist would allow sentiment to interfere with business.” The comments “startled” Hammer at the time, “but they wouldn’t surprise me today.”57 In contrast, Hammer said he never had any dealings with Stalin and that by 1930 “Stalin was not a man with whom you could do business. Stalin believed that the state was capable of running everything without the support of foreign concessionaires and private enterprise.”58

Despite the temporary alliance against the Axis during World War II, the hoped for ‘new world order’ that would see the friendly relations with Stalin continue did not transpire, and Stalin disdainfully rejected US plans for the establishment of a United Nations world government and the “internationalisation” of nuclear energy via the Baruch Plan. The result was the Cold War.59 This, however, only prompted the revolutionary zeal of Big Business, which proceeded to create and fund an anti-Russian Left, which metamorphosed into both the ‘New Left’, and into a post-Trotskyite movement misnamed ‘neo-conservatism’.60 Proceeding from these have been the ‘velvet revolutions’ that continue to convulse the world, and the persistent attitude of suspicion towards Russia, which seems as reluctant now to enter the ‘new world order’ as it did under Stalin.61

Also see Dr. Bolton’s article “Empire of Mammon: Secret History of the World’s Financial Capital” published in New Dawn 133.

Footnotes

1. Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, London: George Allen & Unwin, 1971, Vol. 2, 402.

2. Ibid., 464.

3. Ibid. 402.

4. ‘Who’s Plotting World Government?’, various authors, New Dawn Special Issue 16.

5. Robert Cowley, ‘A Year in Hell’, America and Russia: A Century and a Half of Dramatic Encounters, ed. Oliver Jensen, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1962, 92-121, quoting Thomas A. Bailey, 118.

6. Ibid., 120.

7. New York Times, 24 March 1917.

8. ‘Loans easier for Russia’, The New York Times, 20 March 1917.

9. ‘Is A People’s Revolution’, The New York Times, 16 March 1917.

10. ‘Bankers here pleased with news of revolution’, ibid.

11. ‘Stocks strong – Wall Street interpretation of Russian News’, ibid.

12. Of the 24 members of the American Red Cross Mission, seven had medical backgrounds.

13. Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution, New York: Arlington House Publishers, 1974, ‘The American Red Cross Mission in Russia – 1917’, Chapter 5, 71.

14. ‘Bolsheviki Will Not Make Separate Peace: Only Those Who Made Up Privileged Classes Under Czar Would Do So, Says Col. W B Thompson, Just Back From Red Cross Mission’, The New York Times, 27 January 1918.

15. Ibid.

16. Parvus had made a fortune as an arms and grain dealer in Constantinople. Pearson writes: “Though he still had socialist ambitions, he had become a caricature tycoon with an enormous car, a string of blondes, thick cigars and a passion for champagne – often a whole bottle for breakfast.” M. Perason, The Sealed Train: Journey to Revolution, Lenin – 1917, London: Macmillan, 1975, 58.

17. R.B. Spence, ‘Spies, Lies & Intrigue Surrounding Trotsky’s American Visit January-April 1917’, Revolutionary Russia, London: Francis & Taylor Group, Vol. 21, Issue 1, 2008, 33-55.

18. Ibid. Spence concludes that Julius Hammer is probably the mysterious “Dr M” that Trotsky refers to in his memoirs as befriending the family and taking them for excursions in his chauffeured car. Spence also believes Julius to have been the provider of the Bronx apartment and its furnishings, and the provider of financial largesse that exceeded Trotsky’s meagre income as a socialist journalist.

19. A. Hammer (with N. Lyndon), Hammer: Witness to History, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1988, 188-221.

20. Ibid., 221. Hammer states that he got out of Russia in 1930, discerning that Stalin would not be as favourable to foreign business dealings as Lenin and Trotsky.

21. R.B. Spence, op. cit.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Antony Sutton, op. cit., 60.

25. Ibid., 60-63.

26. However, when Trotsky became Commissar of Foreign Affairs he maintained friendly relations with Bruce Lockhart, who represented the British War Cabinet in Russia, Trotsky hoping for US and British assistance. Trotsky was angrily at odds with Lenin’s policy of armistice with Germany.

27. House was President Woodrow Wilson’s principal adviser and acted for the international banking and business interests. Discerning students of history will recall he was the founder of the omni-present globalist think tank The Council on Foreign Relations, and its predecessor, The Inquiry.

28. Henry Wickham Steed, Through Thirty Years 1892-1922 A Personal Narrative, ‘The Peace Conference, The Bullitt Mission’, Vol II., New York: Doubleday Page and Co., 1924, 301.

29. K.R. Bolton, Revolution from Above: Manufacturing ‘Dissent’ in the New World Order, London: Arktos Media Ltd., 2011, 64-65; Henry Wickham Steed, ‘Peace with Honour’, Paris Daily Mail, 28 March 1922; quoted in Steed, op. cit.

30. S. Gompers, ‘Soviet Bribe Fund Here Says Gompers, Has Proof That Offers Have Been Made, He Declares, Opposing Recognition. Propaganda Drive. Charges Strong Group of Bankers With Readiness to Accept Lenin’s Betrayal of Russia’, The New York Times, 1 May 1922.

31. Not to be confused with the anti-Russian writer and revolutionary propagandist George Kennan, a relative, previously cited.

32. George F. Kennan, The Decision to Intervene, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1958, 17.

33. ‘Memorandum regarding allied war stores lying at Archangel’, US National Archives, Foreign Affairs Branch, Petrograd Embassy, 800 File; March 20, 1918.

34. George F. Kennan, op. cit., 20.

35. Ibid., 21.

36. William S. Graves, America’s Siberian Adventure 1918-1920, New York: Peter Smith, 1941, ‘Aid to the Czechs’.

37. George F. Kennan, op. cit., 35.

38. Michael Sayers & Albert E. Kahn, The Great Conspiracy Against Russia, London: Collet’s Holdings, 1946, 64.

39. William S. Graves, op. cit., ‘The Railroad Agreement’.

40. Capt. Montgomery Schuyler, Report of March 1, 1919, Record Group 120, Records of the American Expeditionary Forces, 383.9 Military Intelligence Report, 2.

41. ‘Kolchak Beaten’, The New York Times, Editorial, August 13, 1919.

42. ‘Semenoff demanded arms of Americans’, The New York Times, November 2, 1919.

43. ‘Says Kolchak’s Staff Joined Revolution. Happenings in Irkutsk Region Before and After Admiral’s Overthrow’, The New York Times, 25 January 1920.

44. ‘Revolt in Irkutsk. Admiral Kolchak Resigns Command. Russian Leader said to be Ill, Names Semenoff as Military Successor’, The New York Times, 28 December 1919.

45. ‘Vladivostok Pro-American. Revolutionist Staff Thanks Graves for Preserving Neutrality’, The New York Times, 15 February 15 1920.

46. J. Smele, Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak 1918-1920, New York: University of Cambridge, 1996, 201

47. ‘Kolchak Sought to Save Companions. 48 Officers and Civilians Refused to Leave Him when Miners Halted Train. Czech Guard Gave Him Up’, The New York Times, 22 February 1920.

48. ‘Kolchak’s Fall’, The New York Times, 30 December 1919.

49. ‘The Vanderlip Concession, an alternate history’, 26 December 2009, www.articlesbase.com/politics-articles/the-vanderlip-concession-an-alternate-history-1626435.html

50. Lenin, 22 December 1920; ‘Speech To The R.C.P.(B.) Group At The Eighth Congress Of Soviets During The Debate On The Report Of The All-Russia Central Executive Committee And The Council Of People’s Commissars Concerning Home And Foreign Policies’, Lenin Internet Archive (2003), www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/dec/x01.htm

51. The Vanderlip project was still proceeding in 1922 when Standard Oil purchased one-quarter of the stock and exclusive rights for oil exploration in the area. However the concession could not become operative until diplomatic recognition. ‘Standard Oil Joins Vanderlip Project’, The New York Times, 11 January 1922.

52. ‘Americans to Trade with Reds’, The New York Times, 15 February 1920.

53. H.G. Wells, Russia in the Shadows, Chapter VII, ‘The Envoy’. Wells went to Russia in September 1920 at the invitation of Kamenev, of the Russian Trade Delegation in London, one of the leaders of the Bolshevik regime. Russia in the Shadows appeared as a series of articles in The Sunday Express. The whole book can be read online at: gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0602371h.html

54. K.R. Bolton, Revolution from Above, op. cit., 32-49.

55. Peter Grose, Continuing The Inquiry: The Council on Foreign Relations from 1921 to 1996, New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2006, ‘Basic Assumptions’. The entire book can be read online at: Council on Foreign Relations: www.cfr.org/about/history/cfr/index.html

56. Armand Hammer with Neil Lyndon, Hammer: Witness to History, Kent: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988, 160.

57. Ibid., 201.

58. Ibid., 221.

59. K.R. Bolton, ‘Origins of the Cold War and How Stalin Foiled a New World Order’, Foreign Policy Journal, 31 May 2010, www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/05/31/origins-of-the-cold-war-how-stalin-foild-a-new-world-order/all/1

60. K.R. Bolton, ‘Trotsky, Stalin and the Cold War: The Historic Implications and Continuing Ramifications of the Trotsky-Stalin Conflict’, The Occidental Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 3 Fall 2010, 75-105.

61. K.R. Bolton, ‘Mikhail Gorbachev: Globalist Super-Star’, Foreign Policy Journal, 3 April 2011, www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2011/04/03/mikhail-gorbachev-globalist-super-star/

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.