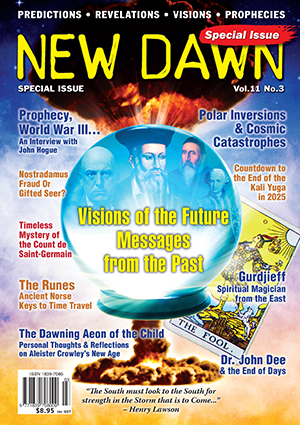

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 11 No 3 (June 2017)

I grew up and went to school in England, and am just old enough that when, age 12, I went to the newly mixed Comprehensive Secondary (which had been until the year before the Girl’s Grammar School), all the atlases and textbooks still spoke proudly of the British Empire.

Our classroom walls were adorned with increasingly outdated maps, showing something like a third of the world coloured red as territories of that Empire – even if by then they had faded to a slightly dusky pink, perhaps faster than memories of British imperialism had faded in the minds of the adults tasked with teaching us about ‘Great’ Britain, its place in history, and the world.

With all of the recent fracas over Brexit, withdrawal from Europe, Scottish and Welsh lobbying for independence, and uncertainty regarding the future of the ‘special relationship’ with its increasingly self-interested and self-isolating Big Brother, America, surely any lingering echoes of that Britain of yesteryear must be long gone? Is it perhaps time to examine the curious origins of the Empire on which, famously, it was boasted the Sun would never set? With all the confusion and pessimism, would it help or make things worse to reflect that the British Empire was birthed amid hopes of re-uniting the faithful of Christendom, and building a New Jerusalem? That its primary architect – indeed, the man who conjured the words ‘British Empire’ for the first time – was in his own lifetime accused of alchemy, necromancy, and worse, and spent the latter part of his life ‘conversing’ with Angels.

It is almost a cliché to speak of Doctor John Dee (1527–1608) as one of the greatest minds of the Elizabethan Renaissance. Professor Ronald Hutton, an expert on Early Modern Britain and authority on historical and contemporary paganism, has said that if one wanted a latter-day comparison for Dee, you could do no better than a figure like Stephen Hawking.

Dee has been largely overlooked, at least until relatively recently, by regular historians and more orthodox commentators on the Elizabethan Age. They are comfortable enough with the idea of Dee the polymath, a sort of one-man clearinghouse for information, putting his knowledge of cartography, optics, and navigation to good use where English expansionism was concerned – but not so sure what to make of a man mostly remembered by posterity, if at all, as a kind of eccentric ‘Merlin’ to Queen Elizabeth I’s ‘King Arthur’.

Alchemist, necromancer, and (alleged) communicator with Angels… a man with the ear of the Queen, involved in Court intrigue, and likely a spy – the good Doctor Dee turns up as a convenient clothes-horse on which to hang all manner of conspiracy theories, historical and supernatural. This is the Dee that performed a ritual with playwright and spy Christopher Marlowe to mark the founding of the British Empire – very possibly the siting of the zero degrees longitude marker at Greenwich Observatory as an act of magical intent, making Britain the centre of Time & Space, a New Jerusalem – and Marlowe was really killed to ensure his silence about this act; Dee not only predicted the storm that favoured the British encounter with the Spanish Armada in 1588, but literally conjured the winds, like a real-life Prospero; Dee designed the mysterious Newport Tower, a massive ruin that stands in the town of Newport, Rhode Island (the approximate location of his proposed North American colony). All extend the already remarkable Dr. Dee into the realm of fantasy.

Undoubtedly true is that Dee put his not inconsiderable energies into a series of works aimed at shifting English foreign policy into a new, expansionist, adventurous mode. The main work – a veritable magnum opus setting forth his ideas regarding a proposed “Brytish Impire” – was the four-volume General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to the Perfect Art of Navigation (1577), previously believed lost, but recently come to light again (shown on page 26). Ensuring his proposal of a British Empire was not missed, Dee designed a frontispiece featuring Elizabeth enthroned at the helm of a ship named Empire, masts topped by symbols of Christ, led on by a winged, sword-brandishing angel – while alongside, Britannia kneels on the shore, beseeching the Queen to protect her Empire by strengthening the Navy. It is as if Dee had woven a veritable spell to enchant Elizabeth: magicians of today would probably consider it a form of Sigil Magic. Roy Strong, author of Gloriana: The Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, described it as a “British hieroglyphic.”

Dee also delivered a smaller, concise work, written especially and exclusively for the Queen, his Brytanici Imperii Limites – “The Limits of the British Empire” – in which he summed up his belief that England’s territorial claim extended far beyond the British Isles, even including a map he had drawn up, indicating what he felt Elizabeth could claim dominion over (sadly, now lost.) Dee’s argument was based on accounts of the voyages of King Arthur, said to have sailed as far as the seas around the Pole in 530, bolstered with references to Brutus, the equally-legendary founder of Britain, and Welsh Prince Madoc, who was believed to have crossed the Atlantic in 1170, proving that:

[of] a great part of the sea coasts of Atlantis (otherwise called ‘America’) next unto us, and of all the isles near unto the same, from Florida northerly, and chiefly of all the islands Septentrional [=northerly], great and small, the Title Royal and supreme government is due.

Arthur, Brutus, and Madoc were all thought authentic historical figures at that time. This was the entire basis of the claim Dee set before Queen and Court: if the so-called ‘New World’ of America was, in fact, the legendary continent of Atlantis, which had been discovered already by these earlier British rulers, then surely Elizabeth, as their descendent, had prior claim?

Dee was not above profiting from the proposed expansion himself. In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert – the man who started the search for the Northwest Passage, thought a route to the Orient, and, like Dee, a believer that America was really Atlantis – succeeded in getting royal backing for a company set up with his brother, Adrian, and half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh, to “discover and settle the northerly parts of Atlantis, called Novus Orbis” (i.e. North America.) Gilbert agreed with Dee that if their mission succeeded, he would get “the royalties of discoveries all to the north above the parallel of the 50th degree of latitude” – in other words, most of Canada and all of Alaska.

In an age ravaged by the schism between Catholic and Protestant, Dee believed in the need for reconciliation. He had been imprisoned as a young man, accused of conjuration and heresy by Queen Mary’s Catholic Inquisition, and was lucky to have survived when many of those around him were tortured or put to death. When his beloved Elizabeth became Queen, the Protestants took their revenge, but Dee wanted the hatred, fear and bloodshed to end. He proposed that in the colony of the New World, all men and women – Catholic, Protestant, and Native – be allowed to live together, peacefully: it would be an example for all Christendom, a veritable New Jerusalem.

At first, Dee’s plans were well received, his sheer daring catching the mood of grand ambition at Court. He helped define the sense of mission, even of destiny, that drove adventurers across the Atlantic. Writing of how English Gentlemen could consider themselves equal to any Frenchman, German, or Spaniard, diplomat Charles Merberry also boasted how “this most Royal Prince (her Majesty’s highness)” [i.e. Elizabeth] could likewise consider herself equal, if not superior, to any foreign monarch, on the basis that:

Master Dee hath very learnedly of late… shewed unto her Majesty, that she may justly call herself LADY, and EMPERESS of all the North Islands.

But it was not to be. Elizabeth’s ever-conservative chief minister, William Cecil, was alarmed by Dee’s vision. He feared antagonising powerful Catholic Spain, and doubted the North American lands would be of much value. Dee had worked hard to conjure a vision that might build a New Jerusalem and ultimately re-unite fractured Christendom, initially capturing Elizabeth’s interest, and the enthusiasm of courtiers such as Robert Dudley and Philip Sidney, but in the end it was all undermined by Cecil.

Not long after, Dee withdrew from such concerns, and ultimately from Court, Elizabeth, and England itself. In March 1582, Dee met a man who would be instrumental in leading him on a voyage of discovery every bit as exciting and, ultimately, hazardous as any exploration into unknown territories. He was none other than Edward Kelley, the man who facilitated his attempts to communicate with otherworldly, non-human intelligences. Soon after, Dee & Kelley embarked on adventures all their own, consuming them for the next seven years, taking them into new worlds beyond this one: The Angelic Conversations – but that is another story…

Ironically, much of what Dee set forth in the writings he put before his Queen did come to pass, one way or another. England broke the monopoly of the Spanish once-and-for-all, with the spectacular defeat of their Armada in 1588 – and, as Dee had proposed, building up the Navy would be the key to English strength on the world stage. North America was colonised, and – although it later required a War of Independence to throw off British rule – the foundations of this particular new world order were indeed based on ideas of equality, fraternity, and freedom from religious persecution.

Certainly the British Empire came into being, and undoubtedly the expeditions Dee suggested and helped plan played a significant part in laying its foundations. But it is hard to believe Dee would have recognised his dream of a New Jerusalem, a utopia worthy of Christ’s return, in the birthing of an empire built on the nightmare of colonialism and imperialism. Ultimately, Doctor Dee’s kingdom was not of this world.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.