From New Dawn Special Issue 11 (Mar 2010)

Caodaism was always the favourite chapter of my briefing to visitors. Caodaism, the invention of a Cochin civil servant, was a synthesis of the three religions. The Holy See was at Tanyin. A Pope and female cardinals. Prophecy by planchette. Saint Victor Hugo. Christ and Buddha looking down from the roof of the Cathedral on a Walt Disney fantasia of the East, dragons and snakes in technicolour. How could one explain the dreariness of the whole business: the private army of twenty-five thousand men, armed with mortars made out of the exhaust pipes of old cars, allies of the French who turned neutral at the moment of danger?

So writes Thomas Fowler, the disillusioned narrator of The Quiet American, Graham Greene’s 1955 novel set in Vietnam in the final months of France’s doomed struggle to hold onto its Far Eastern possession. Fowler, a British journalist covering the war, has taken the day off from his desk in Saigon to go northwest to Tanyin (actually, Tay Nim) province, where he watches a Caodaist religious ceremony.

His cynical description of Caodaism makes it sound as if this esoteric religion, founded in Vietnam in the 1920s, is nothing more than a cover for one of the many private and/or secret armies running wild in Indochina during its rebellion against France. But Caodaism is seen here only through the narrow, atheistic eyes of the embittered Fowler, and is accordingly twisted.

The real Caodaism, however bizarre its trappings, is a vibrantly spiritual faith. It is practiced today by more than five million people in Vietnam, Cambodia, Japan, Australia, Canada, and parts of the US, particularly California. It announces the Tam Ky Pho Do, or Third Period of Salvation, when heaven will reveal itself directly to earth and all religions will unite in mutual understanding.

And, though it’s not even a century old, it sprang largely from the convergence of two rich and ancient cultural traditions in Vietnam: the Chinese and Indian spiritual and religious practices – i.e., Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism – that were brought to Vietnam over two thousand years ago, and the indigenous belief systems of Vietnam – i.e., the land as a place of benign, malignant, and mystical spirits; Hau Bong, or spirit mediumship in the shamanic mode – that stretch back before recorded history.

Channelling and “Saint Victor Hugo”

Two odd phrases stick out in Fowler’s description of a Caodaist ceremony that tell us unequivocally this new religion also has a jarringly modern, esoteric – even beguilingly mysterious – side. The first phrase is, “Prophecy by planchette;” the second is, “Saint Victor Hugo.”

What exactly is “prophecy by planchette?”

A planchette is the tiny, heart-shaped, three-legged marker that scurries across the letters of the alphabet written on an Ouija board and spells out words and phrases said to be communicated by disembodied spirits. It’s the descendant of the three-legged table that, placed on a larger table, with the hands of the medium and one other person lying on its surface, tapped out spirit messages by raising and lowering one leg. Such “table-tapping” was the mode of otherworldly communication preferred by the aristocrats and literati of France when, in the mid-nineteenth century, a tidal wave of enthusiasm for this occult pastime swept across the country.

And “Saint Victor Hugo?”

In 1853–1855, while in exile on the Channel island of Jersey from the dictatorship of Napoleon III, the great French author of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and Les Misérables participated in over 100 table-tapping séances. While other political exiles and members of his family looked on, Hugo chatted with the illustrious dead such as Shakespeare, Molière, Galileo and Luther; legendary animals like Balaam’s Ass and the Lion of Androcles; abstractions like The Novel and India; spirits that had never been alive, like the Shadow of the Sepulcher and Death; extra-terrestrials from Mercury and Jupiter; and the occasional errant Jersey island ghost.

On five occasions – February 11 and 18 and March 8, 15 and 22, 1855 – the spirit of Jesus Christ (or so the transcripts tell us) held forth through the tables to the assembled guests. His subject was the coming of a “third” religion that would supersede Christianity just as Christianity had superseded Druidism (the ancient religion of Britain). Victor Hugo was to be the prophet of this new religion, which held that (1), not only do men and women have individual conscious souls, but animals, plants and stones do as well, and (2), God is in the process of bringing a “universal pardon” to our world, and in fact to every soul in the universe; even Satan will be granted amnesty.

This all sounds strangely familiar to devotees of Caodaism. Some seventy years after Hugo spoke to the spirits on Jersey, 8,000 miles away in Vietnam, the newly-aborning religion would announce itself through spirit guides as, “The Third Great Universal Religious Amnesty.” According to its tenets, God would grant a pardon to all the religions of the world and in so doing bring peace to the universe. At an historic “summit” séance in Saigon on Christmas Eve 1925, attended by members of the Pho Loan group, the powerful spirit having overall responsibility for communicating Caodaism to our world would reveal his true name and declare that he was the reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

All this would happen seventy years after the Jersey séances. Back on that windswept island in the early 1850s, the mysterious process that would somehow transmit the spirit of Jesus Christ’s channelled pronouncements to Saigon in the 1920s and elevate Victor Hugo to the status of Caodaist saint, was putting forth its roots in another direction. The séance transcripts tell us that on September 12, 1853, the “living phantasm” of Napoleon III came to Victor Hugo while the dictator was asleep. A three-hour “trial” of the channelled Emperor ensued, at the end of which Napoleon III humbled himself abjectly before the writer and apologised for the wrongs he had inflicted on Hugo and the world.

This was the last “spirit communication” with the Emperor. But Victor Hugo would never cease to attack the real, living French dictator virulently and publicly. In 1860, Napoleon III, with the British, invaded China. His ostensible motive was to protect Roman Catholicism in that country. The allies inflicted a crushing defeat on a defending army of Tatars that greatly outnumbered them but was short on modern firearms; when the battle was over, 3,000 Chinese, two British, and three French lay dead. Once arrived in Peking (now Beijing), the French and British troops spent days looting, burning and ransacking China’s Imperial Summer Palace, one of the seven wonders of the modern world. The Chinese capitulated immediately.

This piece of imperialist vandalism redoubled Hugo’s hatred of Napoleon III. He wrote, “Imagine some inexpressible construction, something like a lunar building… suppose in a word a sort of dazzling cavern of human fantasy with the face of a temple and palace, such was this building…. One day two bandits entered the Summer Palace. One plundered, the other burned. Victory can be a thieving woman [Queen Victoria], or so it seems… It contained not only masterpieces of art, but masses of jewelry… One of the two victors filled his pockets; when the other saw this he filled his coffers. And back they came to Europe, arm in arm, laughing away. Such is the story of the two bandits.”

The Chinese would gratefully remember Hugo’s rebuke to Napoleon III. The great writer spoke out just as vehemently when, in 1862, the French Emperor invaded Cochin China, again to “protect” Catholicism. By 1869, all of Indochina had been subdued. Vietnam was now a province of the French colonial empire.

When the Vietnamese began to foment rebellion against the French in the early 20th century, Napoleon III was bitterly remembered as the author of all their woes. The Vietnamese held the memory of Victor Hugo dear; he was their defender and their friend.

The Emergence of Caodaism

The séances ended in 1855. In 1870, Victor Hugo, now free to return to France (the Emperor had been deposed), packed the copious transcripts away in a trunk. He had kept all news of the séances away from his political enemies, fearing they might hold up the transcripts as proof that he was a lunatic. The great author died in Paris in 1885. Certain stipulations in his will governed when and if the transcripts could be published.

In 1900, the energies that would create Caodaism began to coalesce around the person of Ngo Minh Chieu (1878–1932), a young Confucian scholar who joined the French civil service in Saigon in 1899. Chieu combined learning in Chinese philosophy with a knowledge of ancient Vietnamese spiritistic-shamanic traditions and Taoist Shamanism, abetting this with wide reading in nineteenth-century European spiritists such as the astronomer/psychic researcher Camille Flammarion; the founder of Spiritism Allen Kardec; Leon Denis; and probably Theosophical Society leader Annie Besant.

Transferred to Phu Quo island, the shy, now isolated adept immersed himself in mediumistic phenomena, using the Cau Co or “spirit pen” to communicate with traditional Chinese deities like the red-faced demon slayer Guan di Gong. He encountered a powerful entity that revealed itself only through the mystical name of Cao Dai Tien Ong Dai Bo Tat Ma-Ha-Tat. He was vouchsafed a vision, probably in mid-1920, of a large eye encompassed by rays of light; this was to become the “Divine Eye,” or “Left Eye of God” (Thien Nhan) that, signifying universal and individual consciousness, is a key icon of Caodaism. Arrived back in Saigon in 1924, the humble modern-day shaman/administrator drew disciples to himself as he studied how to worship Duc Cao Dai.

Now a signal event took place. In 1923, the first collection of the transcripts of Hugo’s channelling experiences – Chez Victor Hugo: Les Tables Tournantes de Jersey – was published in Paris. The volume was highly incomplete, excluding many of the transcripts of the more tradition-challenging séances. It did include Hugo’s five sessions with the “spirit of Jesus Christ.”

Available in Vietnam, and reviewed in the Saigon newspaper L’écho Annamite, the book seized the attention of the many who were still grateful to Victor Hugo. It galvanised a group of young French-speaking Vietnamese civil servants into conducting their own table-tapping experiments. Soon, a spirit calling itself Thuong-De viet Cao-Dai giao-dao Nam-Phuong, or “Jade Emperor, Supreme Deity, alias Cao-Dai, religious teacher of the Southern Quarter,” manifested to announce that it had come to “teach the truth to the people of Annam.”

The group called itself Pho Loan. It was soon instructed to switch from table-tapping to the use of the corbeille à bec (“basket with beak”). Central to this procedure was a wicker basket shaped like an upside-down crow. Four ropes were attached to the basket, each held by a different medium so that no one personality could control the communication. The basket was suspended in such a way that its “beak” could make contact with a flat, fine surface of sand beneath; thus the spirit writings were written in the sand.

On Christmas Eve, 1925, at the previously mentioned landmark séance, the commanding spirit previously calling itself A.A.A. (the first three letters of the Romanised Vietnamese alphabet) now manifested to reveal that its true name was Ngoc Hoang Thuong De Viet Cao Dai Giao Dao Nam Phuong and to affirm its reincarnational identity with Jesus Christ.

It declared:

Be joyful tonight on this the anniversary of my appearance to teach the religion in the West. Your allegiance brings much happiness to me… Soon you must help me establish the religion. Have you seen my humility? Imitate me so that you may genuinely claim to be religious men.

Now Ngo Minh Chieu, whose lived experience of mediumship would be essential to the development of Caodaism, was invited to join the group. It became apparent that he and the Pho Loan members worshipped the same supreme being.

On October 7, 1926, a spirit-dictated petition, signed by 247 Caodaists, gave the French authorities notice that a new religion had been established. The religion held that the world’s misery was caused by the disunity existing between all religions, and that its aim was to perfect the Tam Giao (“three teachings,” that is, Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism) of Vietnam. The religions of the world would be brought into equilibrium.

Increasingly, spirit visitors of world stature manifested through the corbeille à bec. They included Lao-Tzu; Li Po, China’s great 8th century Taoist poet; the female Bodhisattva Quan Am; Joan of Arc; Louis Pasteur; René Descartes; Vladimir Lenin – and, very soon, Victor Hugo. Martin Ebon writes in the Introduction to Victor Hugo’s Conversations with the Spirit World: A Literary Genius’s Hidden Life:

Adherents have meticulously recorded that the first, momentous encounter with this spirit took place on April 20, 1930, at 1:00 a.m., the earthly interviewer being one Ho-Phap. A bit later, the entity said that one prominent Caodaist, Tran-Quang-Vinh, was, actually, a reincarnation of the French poet’s third son, François-Victor Hugo (1828–1873). Tran later became head of the Cao Dai Army, and eventually Minister of Defense (1948–1951) in the ill-fated government of Bao Dai. During a session of the Cao Dai’s legislative body, the deceased Victor Hugo was appointed titular head of the movement’s ‘foreign missions’, that is, its actual ambassadorial representation abroad.

In The Quiet American, Greene’s narrator Fowler fingers General Thé (the name is a pseudonym), the Caodaist Chief of Staff, as a savage and out-of-control ally of the Americans who, already in Vietnam, are attempting, through the “quiet American” Alden Pyle, to create a “Third Force” that will stand up to the French and Vietminh armies. Fowler (but perhaps not Greene) seems almost to assume that politics was the real raison d’être behind the creation of Caodaism, and that it is already badly compromised in what will become the Vietnam quagmire.

Others have wondered about this. In “Through God’s Left Eye” (Underground, Summer 2008), author Paul La Farge asks himself, perhaps with tongue partly in cheek, if some of the more obscure spirit messages might not be coded messages, detailing the movement of troops and supplies. He quotes a message from the spirit of Victor Hugo: “Yes, it’s this kind of gas, which they call hydrogen. More or less dense, which makes the healthiest part, When they say that the Spirit of God swam above the waters, It’s in that sense that the word must be understood…” Professor La Farge wonders if this bizarre message might not be “a Caodaist cipher behind which some violent activity lurked” [meaning, perhaps], “The mortar shells will arrive at midnight, by boat.”

In fact there may be elements of this in Caodaist communications. But the vast majority of Caodaist spirit messages are transparently of deep spiritual intent. In other messages, Hugo spoke eloquently of beauty, divine peace, harmony, science and wisdom. He revealed that “there are… other universes than ours in the infinite and that their creatures know not the word ‘war’.” Moreover, in these worlds “soul-power is master of human weakness.” The Hugo entity averred that “death will be vanquished by uplifted conscience. There is no difference between the living and the dead.”

Caodaism in Modern Times

is located in Tay Ninh, Vietnam. (Photo courtesy en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cao_Dai)

Certainly, in welcoming the spirit of Victor Hugo – and of that great Resistance fighter Joan of Arc! – Caodaism had found a way of allying itself with a hidden Western tradition of anticolonialism. As the number of Caodaist adherents increased almost exponentially, multiplying the need for administrative entities, Caodaism shaped itself into three “powers.” The first – the Eight Sided Temple – consisted solely of spirits, with the 8th century Tang Dynasty poet Li Po serving at one point as “spiritual Pope” in this power. The second power, that of The Heavenly Union Temple, was comprised entirely of mediums, and served as the administrative branch. The third, The Nine-sphered Temple, inspired by the organisation of the Roman Catholic Church, was host to nine hierarchies, including adepts, student priests, priests, bishops, archbishops, principal archbishops, cardinals, legist cardinal, censor cardinals, along with the Pope; this became the executive branch. Women were early on accepted in all these roles. Caodaism’s expanding membership soon called for a church or temple. Spirit guides indicated appropriate land near the capital of Tay Ninh province. Over a twenty-year period, the Tay Ninh Great Divine Temple, with its multiple acres and numerous attendant structures, was built here, emerging as the “Vatican City” – the Holy See – of Caodaism.

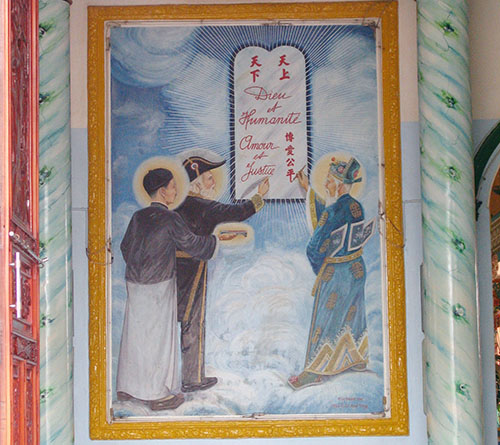

The Tay Ninh temple, although neutered by Vietnam’s post-1975 communist regime and today a quasi-Caodaist theme/amusement part, remains the holiest of the Caodaist places of worship. In The Quiet American, narrator Thomas Fowler lays out for us, if sardonically, its most striking attributes. Entering the temple, he notes a famous mural on the wall:

Saint Victor Hugo in the uniform of the French Academy with the halo round his tricorn hat point at some noble sentiment Sun Yat Sen [the founder of modern China] was inscribing on a tablet, and then I was in the nave. There was nowhere to sit except in the Papal chair, round which a plaster cobra coiled, the marble floor glittered like water and there was no glass in the windows… The dragons with lion-like heads climbed the pulpit: on the roof Christ exposed his bleeding heart, Buddha sat, as Buddha always sits, with his lap empty. Confucius’s beard hung meagerly down like a waterfall in the dry season.

Unremarked by Fowler is best-known feature of the temple: the picture of the “Divine Eye,” or “Left Eye of God” that signifies universal and individual consciousness. This was the eye first seen in a vision by Ngo Minh Chieu.

In the fifth year of its existence, Caodaism boasted 500,000 members. By the 1950s, an estimated one in eight South Vietnamese was a Caodaist. The religion treated Tay Ninh province as if it were a feudal theocracy, collecting taxes for itself and maintaining a standing militia of tens of thousands of men. At the same time, the movement was beginning to splinter into a number of factions, some with marked ideological differences.

The Phnom Penh Post reporter Sebastian Strangio offers a succinct summary of the history of Caodaism from the fall of the French garrison in Dien Bien Phu in 1954 (bringing with it the French surrender) to the present:

But when South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunch Catholic, came to power in 1955, the domestic political calculus began to turn against the Caodaists. In 1956, Diem forcibly disbanded the Caodaist militias and other nationalist rivals. Following the fall of Saigon in 1975, the communists took their revenge, confiscating Caodaist property and arresting or exiling many of its leaders. Relations between the Cambodian Caodaist and the Vietnamese government were difficult during the occupation of the 1980s, but have since improved.

But despite some positive changes, rights groups and exiles say the Vietnamese government continues to ban participation in independent Caodaist factions and oversees all internal Caodaist affairs. “Undercover government agents have infiltrated the administration of Caodaism, and the religion has to function according to the government’s [rules] without respecting the current religious constitution,” said Hum Dac Bui [a spokesman for www.Caodai.org, a California-based non-profit organisation]. “The Tay Ninh Holy See has become more or less a place of tourist interest for the profit of the government and is totally paralysed from a religious point of view.”

“Brad Adams, Asia director of Human Rights Watch, said that only the government-approved Caodaist sect is legally recognised and that those who belong to splinter groups are subject to ‘harassment, arbitrary detention, and imprisonment’.”

The persecution of Caodaists by the post-1975 Communist regime saw a steady exodus of adherents out of Vietnam. Approximately 50,000 have settled in the United States, half of them in California. There are twenty temples in California, most of them small; a temple is under construction in Garden City that will be a miniaturised version of the Great Divine Temple in Tay Ninh.

There are approximately 2,000 Caodaists in Australia today. A large temple was constructed over a period of nine years in Wiley Park, New South Wales. Like the semi-completed temple in Garden City, California, it is modelled after the Great Divine Temple in Tay Ninh.

There are currently over 1,300 Caodaist temples in Vietnam; these serve the great majority of the five million adherents to Caodaism that are spread around the world today.

All that is required in the practice of Caodaism is a vegetarian diet ten days a month and biweekly attendance at services. Doctrinal loyalty is not required. During services Caodaists bow before the Divine Eye, chant, and meditate; sometimes there are addresses. In California, as in other Western places of worship of Caodaism, séances are no longer carried out. If the spirit of Victor Hugo still hovers over this faith, no doubt he has moved on to California, where the dark-blue Pacific can remind him of the dark-blue Atlantic pounding on the shores of Jersey island, where so much of it, so mysteriously, began.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.