From New Dawn 194 (Sept-Oct 2022)

If you stand on top of Canberra’s Mt. Ainslie and look west, your eye will pass over the top of the War Memorial and run along the brown strip down the middle of Anzac Parade towards Lake Burley Griffin. In the middle distance you will see the ‘Wedding Cake’ (old Parliament House) and the ‘Crouching Spider’ (new Parliament House) behind it. The Brindabella Ranges rise in the background.

The roads and buildings below Mt. Ainslie are arranged in circles and lines – flag poles topped with the Australian flag line up reinforcing each other. Straight lines bring strength and harmony into the landscape. Geomancers say that leys (lines linking points) are power paths for ideas and feelings to run along. Such linked points are interactive and become similar over time.

Look down again, and you will see, between the buildings and trees, cars and people. There is a maze of interactions, people going to meetings, shopping, and racing home. Within all this, far more is taking place than the eye can see; the whole makes up the geomancy1 of Australia’s national capital.

Now, look at the War Memorial. There are name plaques for every soldier who died as a personal contribution to the development of the Australian nation. The rising ‘Dome of Remembrance’ contains the body of an ‘unknown soldier’ who acts as a link between the location and the hellish battlefields of Europe in 1917. And it all points down Anzac Parade, along the main Canberra axis line, which ends in Bimberi Peak. Built on either side of the axis line are memorials to the dead. It is here that Australia celebrates Anzac Day, its most prominent ritual of nationhood.

In geomantic terms, our rituals of nationhood are a plea to the essences of the dead to help fulfil the aims of the Australian nation. A request to the souls of the dead who died for “God, King and Country” to help their descendants live peacefully under the symbol of the Australian flag with its Union Jack and Southern Cross.

Why The Canberra Site?

I asked myself this question when I wrote my first Canberra piece, a school text published by Jacaranda Wiley in 1977. The history of the site bears repeating because the thoughts that went into its inception, which carry through in its design, have made Canberra the place it has become.

In the last decades of the 1800s, Australia was occupied by separate British colonies (today’s states) that all referred back to England and not each other. The Germans were in New Guinea and there was the possibility of a German invasion. A combined and effective military force was considered a smart move. There were other reasons – a better postal service, a more effective taxation system, the problem of the vast number of male Chinese immigrants left over from the gold rush, and even the virtual slavery of Islanders in Queensland. It took years for the separate colonies to compromise and sort out these issues, but they finally did, and in 1901 the Australian nation was born.

An unresolved national issue was the location of the seat of Government. Where would the Federal Parliament House be built? Where would the public service work? Neither Sydney nor Melbourne wanted the other city to become the Australian capital, so a compromise was reached. The capital would stay in Melbourne until the new Federal Parliament House was built. And the new capital had to be at least 100 miles from Sydney.

A dozen country towns were considered, from Armidale to Eden, Junee to Bombala, but no decision was made. Then, finally, the ‘Limestone Plains’ location was chosen. Why? It was so inaccessible that Melbourne politicians felt it would take many years for the move to be made from Melbourne – and they were right. The site also had some good things going for it – a bracing climate (memories of Simla, the virtual summer capital of the British Raj in India) but no winter snowfalls. A good clean water supply. An accessible route for a railway link to Goulburn and a further possible route to the Jervis Bay naval base, intended to be developed as Canberra’s harbour. And due to its inland location, the site was safe from the most fearsome and dangerous weapon known to the world in 1910 – bombardment from warships!

The site was called Limestone Plains because it is enclosed by hills to the south, east, and west, with limestone caves under the surface. There are many caves, caverns and sinkholes under central Canberra. Some have strange stories attached to them… aboriginal art, witchcraft covens and unfathomable sinkholes that swallow up foundation piers.

Canberra’s geology is broken and varied with intense underground activity. There are vast amounts of water underneath – probably more than enough for a city of half a million people.

The site’s openness, lack of undergrowth, and treelessness puzzled the first settlers and remained a mystery until the 2003 Canberra bushfires. The blaze, started by lightning strikes in the Brindabella Ranges, swept into Canberra and destroyed 600 houses in an afternoon. Willy willies carried it from updrafts generated by the westerly winds skimming over the ranges. It seems these waves of fire can be expected when enough regrowth provides new fuel.

Hills on three sides contribute to making Canberra seem a place apart, an island in the middle of nowhere. A nowhere from which something new could start. Walter Burley Griffin and his wife Marion Mahoney certainly saw it that way.

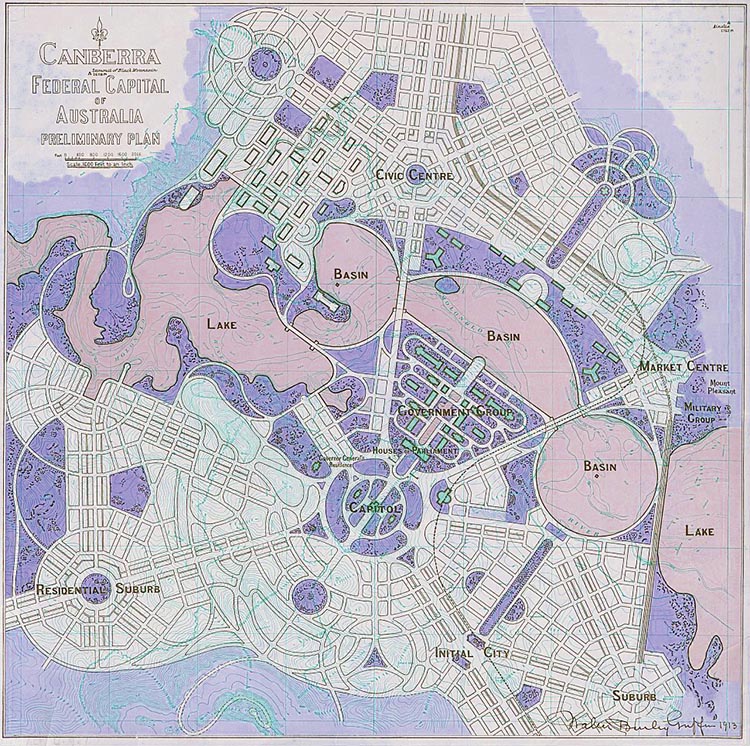

The Griffin Design For Canberra

An international competition was held for the best design. But the competition rules displeased many British and Australian architects who refused to compete. Even so, 137 entries were received by the January 1912 closing date.

On 23 May 1912, entry number 29, by Walter Burley Griffin, landscape architect of Chicago, Illinois, USA, was declared the winner of the competition to design Australia’s new federal capital.

The judge was the Minister for Home Affairs, King O’Malley. By one of those quirks of fate, King, to use his Christian name, was an American real estate developer who gave his birthplace as Canada so that, as a British subject, he could sit for a seat in the Australian Parliament. As an aside, Griffin and O’Malley became friends of sorts but their wives continued to dislike each other throughout their many years of association.

How did they get started on the design? Well, Walter thought about the possible city and did nothing. On weekends, Walter and Marion often took ‘Allana’, their Indian canoe, into the maze of streams near Chicago. One day they paddled 45 miles in stinking hot weather…

The sand was as hot as the top of a stove; we ate our meals in the water. Perhaps it was the torture of those sunburnt legs, perhaps it was just that well-known mean disposition of mine, or it may have been those spiritual advisers, of whom I was unconscious at the time, who said to me, “We can’t do anything with him without some human help. Won’t you do something to make him start on the important matter he has in mind?” – or perhaps it was the suggestion of the Devil himself as Walt was later inclined to think.

Anyway the storm of wrath broke over his head on some such lines as follows: “For the love of Mike when are you going to get started on those Capital plans? How much time do you think there is left anyway? Do you realise that it takes a solid month to get them there after they have started on their way? That leaves exactly nine weeks now to turn them in. Perhaps you can design a city in two days but the drawings take time and that falls on me. Nine weeks! It isn’t possible to do them in nine weeks. I may be the swiftest draftswoman in town but I can’t do the impossible. What’s the use of thinking about a thing like this for ten years if when the time comes you don’t get it done in time? Mark my words and I’m not joking, either you get busy on this very day, this very minute (with rising tones) or I’ll not touch a pencil to the darn things. Serve you jolly well right if I refuse to take it on now. (No, not jolly. Such language only came later).”

And Walt said nothing (he was such an amiable man) but started sawing wood. And so a new adventure was started.2

Marion’s artistic skills were outstanding. She created perspectives in purple and gold that reached from the top of Mt. Ainslie across the Limestone Plain to show a dreamscape of a city to be realised in the morning… it took much longer than that.

I must point out that in those days, the Griffins had no known interest in any esoteric philosophy. Their involvement with Theosophy was to come later in Australia, and it was not until their Castlecrag ‘new age’ community developed that Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy reached their lives. Furthermore, the Griffins didn’t knowingly insert esoteric ideas into their design; Walter just followed ideas he had seen that worked.

A crucial conceptual starting point was the 1893 Chicago World Fair, which aired designs linking avenues, locations, and water. One of those attending the fair, the 17-year-old Walter Burley Griffin, must have been duly impressed.

For Canberra, Griffin used a compass and ruler to draft his design, using the hills marked on the maps as the starting points for his ideas. That’s why Canberra continues to trap the casual tourist – who can expect roads to curve back on themselves?

When the Griffins arrived in Australia in 1913 to oversee the development of the capital, they got into trouble before they started. Walter tended to express himself in complex, even grandiose terms. This added to his dislike by local architects, on top of his disparaging statements about local designs and Australia’s dependency on the British Empire. Government also changed and with it intentions about the building of the new capital, a capital which few – if any politicians – wanted to move to in the first place. And then the First World War swallowed all available funds, and in the midst of conflict the new nation struggled to find itself in the wake of the Anzac debacle.

There was a long and complex Royal Commission into Griffin’s handling of Canberra’s development. Records of the proceedings show that the results were inconclusive. Yes, bureaucracy certainly set out to make his life as difficult as possible. But Griffin was not a good communicator, and one thing led to another. As a result, Canberra’s development and the Griffins parted company in 1920. The couple went on to have a reasonably successful private practice in Sydney and Melbourne.

For anyone curious about the personality and relationships of the Griffins, there is considerable material in the National Library including oral history tapes of interviews with all the people who knew them in the 1930s in their Castlecrag years (also visit the website of the Walter Burley Griffin Society: www.griffinsociety.org)

The Canberra Landscape Temple

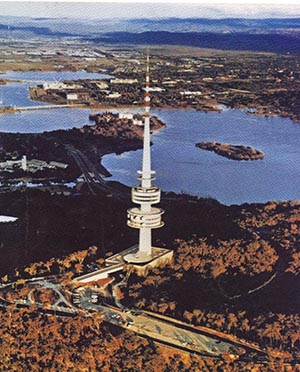

Let’s return to Mt. Ainslie and across to the hill on the right, looking over the downtown area. It’s topped with one of those revolving restaurant ‘space needle’ telecommunications towers that all respectable cities seemed to need in the last century. The hill is known as Black Mountain. Ahead, just to the left of the axis line and near to the ‘crawling spider’ is Red Hill. Below is Canberra’s diplomatic cluster.

That’s three hills, each with different geology and each with its own mood. I’ve travelled from one to another, taking visitors on tour. Our discussions reflect mood changes. On Mt. Ainslie, we look down at the city, think about the future and discuss possibilities. We seem to discuss cars, machines and economics on Black Mountain with its hard, dark rocks and telecommunications hum. Red Hill often results in a clash of personalities between myself and visitors, “You’ve taken me around, and now you want me to believe your perceptions, I don’t see why I should!” It makes me feel I’ve just stepped into a diplomatic meeting or question time in Parliament.

Yes, each of the three hills has its own “personality,” its resident consciousness that affects the people standing inside its energy field. These natural “Dreaming” locations are as real as the spaces we make inside our buildings. The strength and size of these radiating fields vary – nothing in geomancy is truly stable. Times of day, astrological conditions, rituals performed – all have an effect. Sometimes Mt. Ainslie is strong, extending across the Limestone Plain to affect the mood of people below; at other times and on other days, Black or Red is larger and more powerful.

The energy of these three mountains is reflected in the three apexes of the Parliamentary Triangle that Griffin put in place. City Hill, in downtown Canberra, watches over money and construction. Parliament House Hill is about personal power and arrogance – reflecting the proximity of Red Hill. The apex near the War Memorial is about the love for the dead Australian soldiers who gave their lives for the nation. There is a little hill at the apex of this corner of the triangle, between houses and defence department offices, called Peace Harmony Hill. Griffin’s original plans placed Australia’s National Cathedral (non-denominational) at this location.

There are two triangles in Canberra that interlock and interrelate. Inside these the business of the nation is carried out. When politicians sat inside the Wedding Cake – the original Parliament house – the interflows between love, money, and pride worked reasonably well. The Australian nation’s Dreaming, more or less, worked. New Parliament House is located on the apex where Griffin conceived a garden with a central gazebo-style monument to celebrate the Australian nation. It is the strongest site in Canberra, connected to the central axis and the parliamentary triangle. Griffin saw it as a people’s park belonging to everyone in the nation.

But alas, the new Parliament House swallowed the Capital Hill site. This creates an unfortunate situation that makes pride and personal power far too important in the minds of those who control the nation. It is not just the proximity of Red Hill that is an issue, there is also the architectural oddity of a building that replaces a hill. Capital Hill was removed, a billion-dollar building put in its place, and grass planted on top. To make matters even more geomantically undesirable, the whole structure is cut into the large and unstable Lake George fault line. In the symbolic language of geomancy, one could say the building is a gateway to the underworld, and lacks a Buddha and chanting nuns to keep the necessary balances between the spiritual worlds, Earth and the underworlds.

As for Old Parliament House, a visit is a good lesson in how the energies of place interact with our moods and thoughts. Wander down the corridors and go into the Prime Minister’s office. Sit down on a visitor’s chair, lightly meditate, and you may get the same feeling of complexity I got when I did this exercise. Being PM in this office was a difficult job. How does one control situations rather than be controlled by the whirl of events? The old reading rooms give one the feeling of a gentleman’s club. For decades, Canberra wasn’t on the artistic, social, or cultural map.

One evening I was at a wedding reception in the lightly remodelled member’s bar and restaurant in the back of the building when suddenly, at 10 o’clock, the mood changed. The atmosphere filled with what is known in Buddhist metaphysics as “hungry ghost” energy forms (desire elementals) that searched out the heavy wine and spirit drinkers in the room, compelling a recharge of glasses. Many of Australia’s early parliamentary processes must have taken place in a haze of hangovers and alcohol.

Down The Main Axis Linking The Past To The Future

Let’s journey down the main Anzac Parade axis, lined with monuments to people who fought and died in wars, making links between the nation’s past, present and future. There are vacant spaces for more monuments – reserved for the future when there will be more heroes and certainly more deaths to keep the Australian nation alive.

Crossing the lake, one comes to Commonwealth Place, a lakefront forecourt where bands occasionally play. An almost subterranean passageway links it to a grassy hill named Reconciliation Place. The location is a weird bit of geomancy, an attempt to show how British Commonwealth Australians and Aboriginal people have reconciled their differences. By what one would hope is an error of judgement – rather than a result of conscious intent – Reconciliation Place resembles a burial mound or perhaps a mass grave. I’ve been told that, like so many places in Canberra, it links the city to the underworld; in this case, to Aboriginal ancestors who emerge to participate in events when they feel the need and disappear when their mission is complete.

There are many other sites to tell of Canberra. But to keep the story in line with revealing how the geomantic past creates frameworks for future decisions, I need to tell the National Museum story that involved me because of my geomantic interests.

Alas, for Australia, the Museum is a geomantic opportunity lost. The site is touched on three sides by Canberra’s central lake and was the site of Canberra’s original hospital. The hospital reached its use-by date and was demolished, leaving the site open for redevelopment. Many groups claimed the site, and much community discussion followed.

Finally, the National Museum of Australia won the site. Guidelines for a competition to create the prize-winning design were drawn up. The guidelines were exciting – they called for a multicultural museum and a complex of separate buildings spread over the peninsula. Each cultural group was to have its own building, the Aboriginal building was to be large, so were the Greek and Italian buildings. Smaller groups were to have use of buildings for periods. The whole was conceived as a place of continual festival, a celebration of the unfolding strengths that multiculturalism gives Australia.

But it was not to be. Instead of structures that used the energetic potential inherent in the site – with its water and vistas – a building was chosen that looked more at home in an industrial area in Berlin, inward-looking with the vistas hidden behind dense shade cloth. The building opened in 2001 and cost $152 million to complete. The museum’s initial displays radiated out from the time of “Coronation Australia,” the period in the 1950s when the British colonial perspective still made sense.

Why did this happen? Why wasn’t the site made a location for the ongoing celebration of a multicultural Australia, an Australia built on constant immigration?

The Whitlam years, with their Al Grassby openness, gave Australian power brokers an awareness that a new Australia was possible, but also one in which power might shift away from the ruling concepts and frameworks locked into the idea of “God, King and Country” enshrined in the War Memorial and Anzac Parade.

I think it is a shame Australia’s self-perception as a multicultural nation, brimming with new life and activity, has been stultified. Instead, we struggle in an underworld linked to the past, to souls that “gave of themselves so that we could live.”

Foundations are very important because the original intentions of founders – like energy – stream forth into structures like cities to shape the future for their inhabitants. Well before the word Canberra had entered his mind, Walter Griffin – like so many other thinkers of the time – was inspired by the influential book Progress and Poverty by Henry George, written in the late 1870s.

George dedicated the book with the following words, which I believe inspired the Griffins on their Australian adventure:

To those who, seeing the vice and misery that spring from the unequal distribution of wealth and privilege, feel the possibility of a higher social state and would strive for its attainment.

I see the spiritual basis of Australia’s capital city as originating from this short quote. The rationale behind Canberra was that it would serve to unite the rivalries that separated State capitals and make the development of a united Australia possible.

Perhaps things would change for the better if we allowed Canberra’s spiritual forces to work into our doings. What can we do to overcome the forces of hindrance that hold us back from developing our future potential?

This article originally appeared in New Dawn 94 (Jan-Feb 2006).

Footnotes

1. Chinese geomancy, generally called Feng Shu, is a collection of systems that evolved to help people understand and adjust the spirits of place – whether these are resident above or below or linked to the past or the future.

2. From The Magic of America, Marion Griffin’s writings compiled in the later years of her life (she was 91 when she died in Chicago). Extracted from Ron Evans’ collated and edited version titled Marion’s Magic (1991), page 26.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.