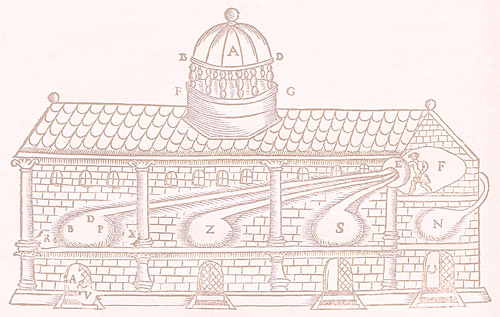

The museum of Athanasius Kircher (1602 – 1680) in the Jesuit College of Rome was an obligatory stop for high-class tourists, from John Evelyn the diarist to Queen Christina of Sweden, but they never knew what to expect. The college porter would report their arrival via an acoustic intercom (see illustration 1), and Kircher or some young assistant would set the machines going.

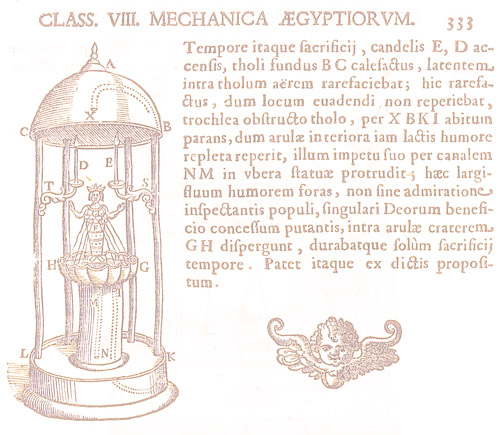

As the visitors entered the museum, everything was abuzz. A statue of the Goddess Isis might greet them by spraying water from her multiple breasts (see illustration 2). A mechanical lobster might vomit up various liquids for their refreshment. Clocks played hymns and told the time in every country of the world. A statue called the ‘Delphic Oracle’ would answer any questions one put to it, probably in suitably gnomic terms, for to tell the truth it was connected by a tube to another room where a stooge was placed. Alternatively soft chamber music might issue from its mouth. A miniature of the Colossus of Memnon, the famous sounding statue of Egyptian Thebes, would greet the sun with the music of plucked strings.

Once some visitors, coming inside on a cloudless day, were promised rain, and as they scoffed, Kircher turned on a hidden tap and drenched them with an artificial shower. Other devices simulated perpetual motion, or presented edifying religious themes, like the resurrection of Christ in a glass sphere. Much was done with mirrors and magnets, and of course there was the famous magic lantern, projecting a frightful image of a soul in Hell.

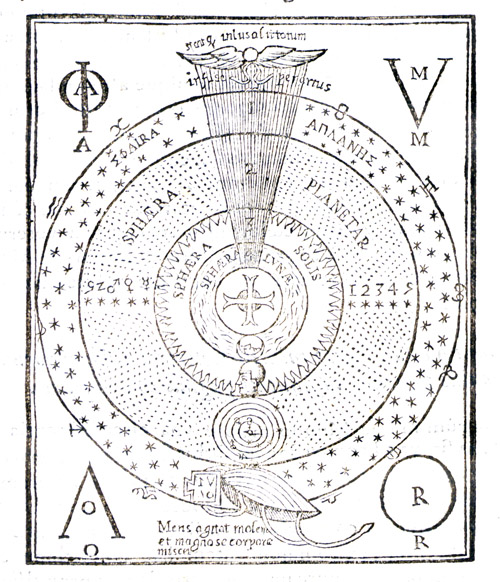

While Father Kircher certainly had a sense of humour, every one of these contraptions had a serious side. One would have to plunge into his books, some of them a thousand pages long and all in Latin, to understand how magnets manifest the cosmic quality of attraction, which is in turn an image of Divine Love; how the ancients used machines just like Kircher’s to fake the miracles of their idolatrous and demonic religions; how water can be forced to defy gravity, as it does in Nature when the winds drive it into the vast caverns concealed beneath every mountain range (see illustration 3).

Kircher explains how music enters the ear and stirs up the subtle spirits that permeate the body, causing delight; how the heavenly bodies mark time, which can be measured by sundials, moondials, and even a sunflower; how the metaphysical principles of light and darkness govern the visible world.

1. Bugging a Building. The man in the upper room (F) is able to eavesdrop on conversations in all the other rooms of the building, as their sound is gathered in their domed ceilings (D, Z, S, N) and funnelled to point E. (Musurgia Universalis, 1650, II, 296)

2. The Great Mother Goddess. When the candles (D, E) heat the upper dome, expanding air goes down the columns and forces the milk in the lower cylinder up (as in a coffee percolator), to issue from the statue’s breasts. (Oedipus Aegyptiacus, 1652, II, ii, 333)

3. Where Rivers Come From. The action of the wind causes the sea to form whirlpools, driving the water inland through underground channels. These disgorge in huge caverns beneath the mountains, whence the water issues as rivers and returns to the sea. (Mundus Subterraneus, 1665, I, 254)

If the visitor was not merely a tourist but a fellow scholar, Kircher could produce manuscripts in every known language – and he seemed to know them all. He had, after all, deciphered the most enigmatic of writings, the Egyptian hieroglyphs. There was a large collection of artefacts from non-European cultures, for the Jesuits were busy as missionaries in every known land. They had special instructions to send reports and anything portable back to the museum in Rome (and a few of them are still there).

Kircher explained that idols from China and India, Mexico and Peru were nothing but degraded images of Egyptian gods, and these in turn were the personifications of the forces of nature, mistakenly worshiped. He could show how the human race had all descended from the four couples saved in Noah’s Ark, and how the universal language had split into today’s multiple tongues. That was the fault of Nimrod, the presumptuous builder of the Tower of Babel, which was supposed to reach the Moon but now lies in a heap of ruins. Kircher could pass around a brick salvaged by an explorer from that very tower.

Along the centre of the museum stood a series of model obelisks, copies of the ones that had been shipped from Egypt and erected by various Roman emperors. With irresistible conviction, Kircher read their hieroglyphic inscriptions, not as the dull records of pharaohs but as sonorous prose-poems treating the origin of the cosmos, the workings of the elements, and the wonders of Egypt’s life-giving river.

In Kircher’s mind, everything was connected to everything else. “All things are at rest, bound by secret knots,” he wrote in his book on magnetism. The past was an open book: given sufficient erudition, it would be possible to trace all languages, migrations and religions to their source, as surely as the River Nile sprang from a cavern beneath the ‘Mountains of the Moon.’

He held to the Hermetic doctrine that the human body, a microcosm, reflected the macrocosm, so that every organ was ruled by a planet, every part by a sign of the Zodiac from Aries at the head to Pisces at the feet. Every beast, bird, tree, plant, and rock had its place in the same scheme of universal correspondences. To understand these, and to put them to work for healing and other purposes, was the task of the natural magician.

He also knew how to exploit the invisible powers of nature such as the magnet. But Kircher’s magic was strictly natural, for he was a faithful son of the Catholic Church, and a member of its most zealous monastic order, the Society of Jesus. Any other type of magic, such as the invocation of the planetary spirits or the juggling of kabbalistic formulae, he considered as extremely dangerous, and more than likely to invite demons in disguise.

By the time of his death Kircher’s world view was already under demolition by the Scientific Revolution. For much of his life he had passed as the man who knew everything, but now his reputation for universal knowledge crumbled, his open mind dismissed as credulity. Some critics suggested that his decipherment of the hieroglyphs, once the admiration of popes and emperors, was sheer fantasy, and when Champollion finally found the key to them in the 1830s, this was confirmed.

But consider his list of ‘firsts.’ The books that Kircher dedicated to the Coptic language, Egyptology, geology, acoustics, and China were the first works in their field. His successors might disagree with his conclusions, but nowhere else could they find such a rich collection of material on which to base their own theories. Kircher published the first map explaining how ocean currents work; the first map showing how the continental shelves were once dry land; the first map of the source of the Nile, and the first of the mythical island of Atlantis.

In the oriental field, his book on China contained the first Western picture of a Dalai Lama and of the Potala monastery-palace in Lhasa. It was the first to show the letters of Sanskrit and images of the Ten Incarnations of Vishnu. It reproduced an inscription of over 1,000 Chinese characters that proved there had been Nestorian Christians in China.

Kircher was the first to compile a Coptic dictionary, to make a scientific study of volcanoes (descending into the crater of Vesuvius as it was erupting); the first to build a machine for composing music and another for sending messages in code. He was the first to propose that diseases were caused by germs, rather than by an imbalance of humors, pestilential vapours, or the wrath of God. If he did not actually invent the magic lantern, ancestor of the cinema, he first illustrated and explained it.

But in other respects, Kircher came last. He was a late relic of the medieval frame of mind, obedient to the Bible as a source of scientific as well as salvific knowledge. In another respect he was the last Renaissance man, proudly mastering all human knowledge while this still seemed possible. More accurately, he was the last of the Renaissance Hermeticists in the line of Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, faithful to their idea that not just the Jews but the pagans had received a revelation of divine wisdom. He was one of the last scientists to insist that the earth was the centre of the universe (see illustration 4), though it is never clear whether he was just following the party line, as Jesuits were obliged to do until the nineteenth century. He did not believe in unicorns (he knew that their “horns” came from the narwhal) but was sure that Adam and Eve spoke Hebrew, and that dragons still lived in the Swiss Alps.

4. The Sphere of Love. Kircher invented this hieroglyphic diagram to show how the World Mind (represented by the scarab beetle) infuses the entire universe with love. The concentric spheres represent the fixed stars, the five planets, the sun, moon, and earth. The letters in the corners spell “love” in Coptic letters (PHILO) and in Latin (AMOR). Kircher believed he had discovered them on the Isiac Table, a pseudo-Egyptian artefact from Rome, and made them the basis of his decipherment of the Egyptian hieroglyphs. (Oedipus Aegyptiacus, 1652, II, ii, 112)

These facts aside, Kircher had an exuberance and a theatrical flair typical of his own, Baroque era. It is this flair that led him to have his books copiously illustrated, first by local artists in woodcuts, then, as his reputation grew, with the more expensive medium of engraving. After he switched publishers from Rome to Antwerp, his books became more splendid still. The illustrated volumes on the Subterranean World, China, Latium, Noah’s Ark, and the Tower of Babel have always been treasured by book collectors, whether or not they read them.

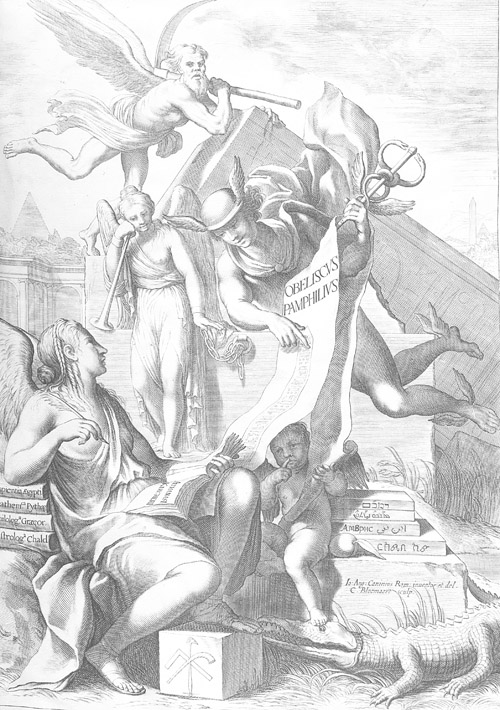

The illustrations of Kircher’s works range over tarantulas and snake stones, machines of past and present, suggestions for future machines, mummies, obelisks, oriental scenes, giants, pictures in rocks, pagan divinities, diagrams of the earth’s interior and of Noah’s Ark, wonders of the ancient world, musical instruments, magnetic devices, and much more. They are a delight in themselves (especially, I find, to precocious children), but many also contain enigmas and meanings that need to be teased out, if their full import is to be appreciated. This is especially true of the frontispieces that summarise the whole message of a book in visual form (see illustration 5).

5. Hermetic Inspiration. Old Father Time has toppled the Pamphilian Obelisk. It lies among the undergrowth, its Fame sadly chained to it. But there is hope! Hermes has come to interpret the hieroglyphs to Kircher’s Muse, who sits backed by ancient texts and ready to write. Harpocrates, infant god of silence, subdues the evil crocodile and indicates that only part of the mysteries are revealed here: we must wait for Kircher’s masterwork Oedipus Aegyptiacus to learn the rest. (Obeliscus Pamphilius, 1650, frontispiece designed by Giovanni Angelo Canini, engraved by Cornelis Bloemaert)

I like to imagine how Kircher wrote out his thousands of pages by hand, with their multiple languages and scripts, sketched the hundreds of illustrations, submitted his work to the church censors, and then sent it to the Low Countries by wagon, hopefully avoiding war zones. Joannes Jansson, the publisher, organised a small army of engravers who cut every sketch into blocks of boxwood. He or Kircher hired more prestigious artists to draw the frontispieces and the major illustrations, which were then copied onto copper plates, in mirror image, and had to be printed by a special process. Some of them are folding plates two feet tall. Then the whole thing was assembled, indexed, proofed, printed, bound, and shipped around the world with no more delay than a modern publisher takes from manuscript to finished book. And all this without the communications systems that facilitate and bedevil our lives.

No one today can rival Kircher in knowledge and industry, but that is no reason to give up on understanding what his work was about, and what it has to offer us. He could not be otherwise than Catholic in his core beliefs, any more than people today can abandon their ingrained faith in scientific and political principles. But he gives access to something beyond religion, science, and politics. These come and go, but the nature of things does not change, and exceptional humans have periodically gained some insight into it. This is the meaning of the Renaissance concepts of the prisca theologia (ancient theology) and the philosophia perennis (perennial philosophy), handed down in the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, the Chaldaean Oracles of Zoroaster, the Hymns of Orpheus, the Golden Verses of Pythagoras, the dialogues of Plato, and the treatises of Neoplatonists such as Plotinus, Iamblichus, and Proclus.

The Hermetic writings seem to sum it up with their teaching of the intelligent design and harmony of the universe, the essential goodness of the world, the invisible web linking all things together, the place of the human microcosm in the cosmic hierarchy, and the destiny of the soul as it descends into the body and leaves it again. This is the heart of the Western Esoteric Tradition. It does not threaten eternal damnation, despise nature, or condemn the material world as evil. To embrace it is a gai savoir, a joyful learning, and Kircher’s example, with all his earnestness, oddity, curiosity, and humour, is an inspiration to do so.

Illustrations 1-5 courtesy of Cornell University Library.

Athanasius Kircher’s Theatre of the World is published by Thames & Hudson, London, 2009 (hardcover, 320 pages, 431 illustrations, ISBN 9780500258606). The book is also published in the USA by Inner Traditions, www.innertraditions.com, ISBN 9781594773297.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.