From New Dawn 190 (Jan-Feb 2022)

Shortly after 9:00 pm on 27 February 1933, alarm bells clattered in fire stations across Berlin. The Reichstag, the massive glass-domed home of the German parliament, was ablaze. The first fire crews arrived within minutes, and it was immediately apparent that separate fires had deliberately been set throughout the parliament using flammable liquid. Despite their brave efforts, the Reichstag was destroyed. What the firefighters could not know was that they were witnessing thekey event in establishing Nazi Germany and a defining moment of the twentieth century. All of Europe and much of the world, like the Reichstag, would soon be engulfed in flames.

With the Nazi party facing losses to communists at the forthcoming general election six days’ later, Hitler blamed them for destroying the home of German democracy. A young Dutch leftist, Marinus van der Lubbe, would be executed for the crime. A communist revolution, Hitler informed the nation, was imminent, and the Reichstag fire was part of a Bolshevik plan to seize power. The communist vote consequently slumped at the election while the Nazi party’s share increased dramatically to make them the largest party. Hitler seized power, suspended the constitution, and sent communist members of parliament to Dachau concentration camp. Within weeks all political parties in Germany apart from the Nazi party were banned. Historian Professor Antony Sutton relates: “From that point on there was no turning back for Germany; the world was set upon the course to World War II.”1

Van der Lubbe was a patsy, and it is clear nearly ninety years on that the fire was deliberately started not by communists but by the Nazis themselves. Astonishingly, the man who deployed the arsonists that night, Ernst Hanfstaengl (known to all as Putzi), was a Harvard University graduate and secret agent of the closely collaborating Anglo-American secret intelligence services. As such, he spent almost 17 years at Adolf Hitler’s side, grooming him for power. Some readers may find that hard to believe but read on and examine the evidence before dismissing it. In his book, Conjuring Hitler: How Britain and America Made the Third Reich, historian Professor Guido Preparata details how the Anglo-American elites funded Hitler and the Nazis throughout the 1930s and armed them to the teeth.

It was an astounding political manoeuvre willingly performed by the Allies to resurrect in Germany a reactionary regime from the ranks of her vanquished militarists… with a view to conjuring a belligerent political entity which she encouraged to go to war against Russia: the premeditate purpose was to ensnare the new, reactionary German regime in a two-front war (World War II), and profit from the occasion to annihilate Germany once and for all.2

We contend it would be a misconception for anyone to think British and American banking and political elites brought Hitler to power because they respected him or his politics or hoped Germany would thrive under him. In reality, the destruction of Germany once and for all as an economic, commercial, and industrial competitor was the goal of this hideous Anglo-American bankers game.

Who was Putzi Hanfstaengl?

Putzi Hanfstaengl was born into an extremely wealthy family in Munich in 1887. Two years later, when Diphtheria brought him close to death, he was saved thanks to three days of round the clock attention from an old family servant. Throughout, she repeatedly crooned, ‘drink, Putzi, please drink Putzi’, encouraging him to take sips of water. The name, a Bavarian term of endearment for ‘little fellow’, stuck throughout his life despite growing to a six-foot-four towering hulk of a man with an enormous head, prognathous jaw, and huge hands.

Putzi and sibs had three governesses and were educated privately at top German schools. He was an accomplished classical pianist, taught by the cream of European musicians. Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt, and Richard Straus had been friends of his parents and grandparents before he was born. Mark Twain was another. Putzi was named after his father’s godfather, Duke Ernst of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the brother of Prince Albert, who married Queen Victoria.

Putzi’s mother was American, and he always considered himself half American. Like his father, she came from an extremely wealthy and well-connected family. Several of Putzi’s forebears were famous Union Army Generals and close friends of Abraham Lincoln. His mother’s cousin, General John Sedgwick, fell in the Civil War and is honoured by a statue at West Point. His grandfather, General William Heine, helped carry the coffin at Lincoln’s funeral.

Between 1905 and 1909, the young Putzi attended Harvard, the oldest and most prestigious university in America. He was immediately taken under the wing of his American relative, the famous and well-connected president of the university, Charles William Eliot. Highly popular at Harvard, Putzi regaled his fellow students with fight songs at pep rallies for the football team, songs that would later inspire him to compose Nazi marching songs.

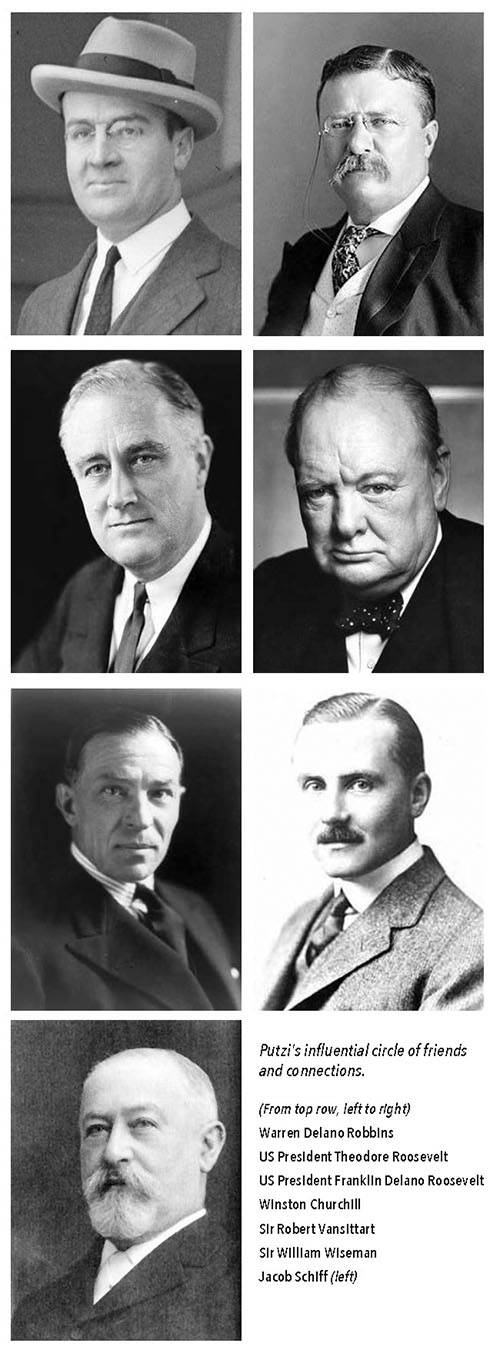

Putzi befriended many important individuals such as President Theodore Roosevelt and future President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and mixed at Eliot’s home with men at the very top of Wall Street banking such as J.P. Morgan and Jacob Schiff. A close friend of Charles Eliot’s, Jacob Schiff, is known to have funded Trotsky in preparation for the Bolshevik revolution. Putzi regularly played the grand Steinway at White House parties and frequented the President’s summer retreat at Sagamore Hill. This, together with many more famous names, was the undergraduate milieu of Putzi Hanfstaengl.

After graduation, Putzi served for a year in the elite Royal Bavarian Foot Guards. Like the regiment, he was unstintingly loyal to the monarchy. He returned to the US to run the family art gallery on exclusive Fifth Avenue, mixing with famous personalities such as Henry Ford, Charlie Chaplin, Toscanini, and the great Caruso. Unlike many young German Americans, Putzi made little effort to return to Germany when the country went to war in 1914. And, unlike others of German origin, he was never harassed or interned when America entered the war in 1917. Putzi dined every day at the exclusive Harvard Club in New York, socialising there and elsewhere with many international celebrities, leading politicians, and Wall Street bankers. Across the Atlantic, he was a friend of Winston Churchill and other members of the British ruling class. What does it tell us that he associated with Sir Robert Vansittart, a leading figure in the British Foreign Office and Secret Intelligence services?

During his ten years in New York (1911-1921), Putzi also associated with agents of the British secret service operating in the city, including the infamous Aleister Crowley, who was deeply implicated in the false-flag sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. British agents were active there with the consent of the US government and in the closest collaboration with the nascent US secret services. The head of British Secret Intelligence in the US, Sir William Wiseman, was a close friend of banker Jacob Schiff whom Putzi knew well. It was to this closely allied Anglo-American Secret Intelligence network that Putzi Hanfstaengl enlisted during WWI. Despite utterances otherwise, his allegiance now lay very firmly with America and Britain, not Germany.

In late 1921 after spending the greater part of the past 17 years in America, Hanfstaengl, now age 34, gave up his wonderful life there and took his American wife and baby son, Egon, to Germany. Why? What on earth possessed a wealthy, well-connected now-American businessman with a beautiful young wife, Helene, and baby son Egon, to move to a country riven by faction and utterly desolate thanks to the war, raging inflation and widespread poverty? On arrival in Munich, they even found it impossible to get milk for their child. Putzi’s stated reason for going because he felt “nostalgic for his native land” is surely not credible.

The Rise of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler’s background was the polar opposite of the well-bred, highly educated, sophisticated and cultured Putzi’s. Born in Austria, Hitler’s mother was a peasant girl, his father a minor civil servant who was allegedly often drunk and beat him. Sent to local village schools, he showed little interest in education. The teenage Adolf demonstrated an aptitude for art but twice failed to gain a place at the Art Academy. For years he was an unemployed, friendless vagabond living in men’s hostels or sleeping on park benches. The unhappy, angry, and frustrated artist survived by earning a few pfennig’s painting and selling postcards on the streets. Hitler was turned down by the Austrian army as too weak to handle weapons but found a place in the German army during WWI as a dispatch runner. He suffered a shrapnel wound to the leg at the Somme in 1916 and was gassed and temporarily blinded at Ypres in October 1918. When the war ended, he decided to stay in the army for another two years. Awarded the Iron Cross first class for bravery, he proudly wore the medal for the rest of his life. In 1920, Hitler ended six years of military service as a lowly lance corporal. Biographer William Shirer writes:

As soldiers go, he was a peculiar fellow, as more than one of his comrades remarked. No letters or presents from home came to him as they did to the others. He never asked for leave; he had not even a combat soldier’s interest in women. He never grumbled… and was the impassioned warrior, deadly serious at all times about the war’s aims and Germany’s manifest destiny. “We all cursed him and found him intolerable,” one of the men in his company later recalled.3

Hitler re-joined the ranks of the unemployed, rented a tiny, cheap room in Munich where he lived a shadowy existence and took to the beer halls as a political agitator. He was but one of the hundreds of similar rabble-rousers in the political turmoil of post-war Munich. Rare mentions in local newspapers failed even to spell his name correctly. Putzi describes Hitler as being like an awkward “down at heels clerk” or a “suburban hairdresser on his day off.” However, his ability as an orator to incite crowds brought him to the attention of the Allies. Planning to fund and build a reactionary movement in Germany, the Money Power was on the lookout for a suitable reactionary to run it.

In Munich in 1922, Putzi got the call to action from an old Harvard friend, Warren Delano Robbins. Now second in command at the American Embassy in Berlin, Robbins just happened to be a first cousin of Putzi’s close friend, future President F Delano Roosevelt. The ruling elite’s tentacles were ubiquitous. He would send the embassy’s military attaché, Truman-Smith, to Munich to discuss political events in the city with Putzi. Individuals in such embassy positions are not simply regular bona fide diplomats. To put it bluntly, military attachés act as secret agents and spies, and Truman-Smith was no exception. He arranged for Putzi to attend a beer hall meeting in Munich where an as yet little known 32-year-old called Adolf Hitler would be speaking.

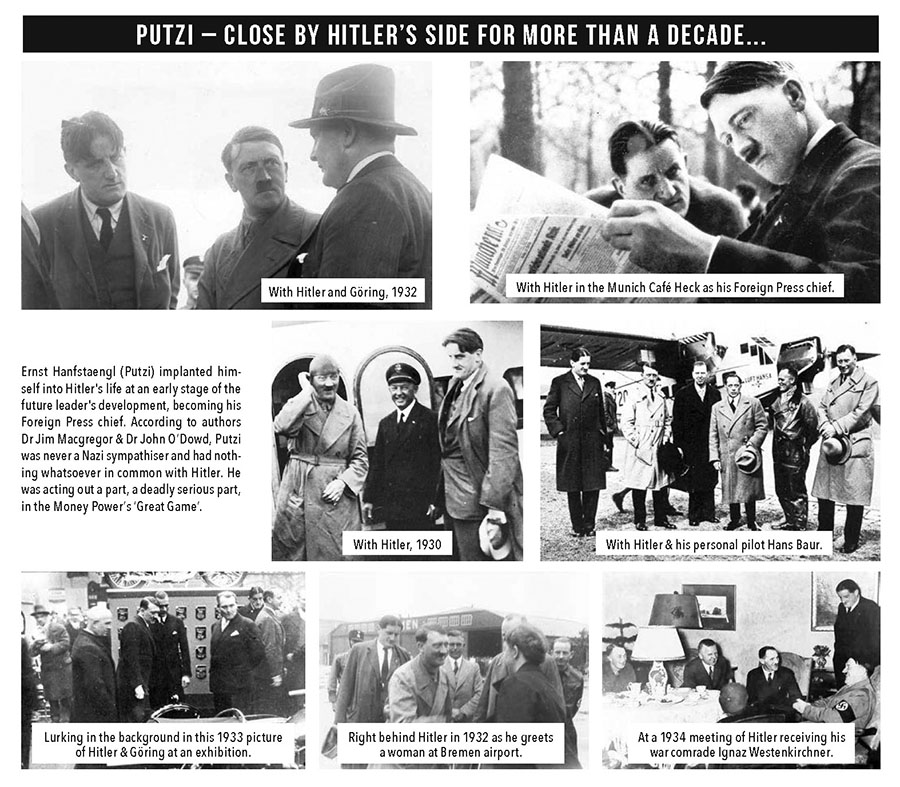

Having clearly been forewarned by Truman-Smith, Hitler shook Putzi’s hand and greeted him warmly when he approached and introduced himself, “Ah, yes, the big American.”4 Putzi feigned Nazi sympathies, inveigled his way into Hitler’s company, and quickly became the otherwise friendless loner’s bosom buddy. It should be understood from the outset that it was a charade. Putzi was never a Nazi sympathiser – probably detested them if truth be told – and had nothing whatsoever in common with Hitler. He was acting out a part, a deadly serious part, in the Money Power’s ‘Great Game’.

The ghostwriter of Putzi’s ‘autobiography’, Brian Connell, states that Putzi’s task was “to mould into some statesmanlike form the spell-binding oratorical gifts and immanent potential of Adolf Hitler and make him socially acceptable.”5 Putzi himself relates that Hitler was open to influence and he “felt encouraged to continue exerting all he could.” Putzi ploughed money into the small Nazi newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, enabling it to purchase more printing presses, triple its size and increase circulation.

Hitler dined regularly at Putzi and Helene’s home and played on the floor with his godson, Egon. Much to Hitler’s joy, Putzi would hammer out Wagner pieces on the piano. He also played football marching tunes picked up at Harvard.

I explained to Hitler all the business about cheerleaders and marches, countermarches and deliberate whipping up of hysterical enthusiasm. I told him about the thousands of spectators being made to roar “Harvard, Harvard, Harvard, rah, rah, rah!” in unison and of the hypnotic effect… I even wrote a dozen marches or so myself over the course of the years. Rah, rah, rah! became Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil! but that is the origin of it and I suppose I must take my fair share of the blame.6

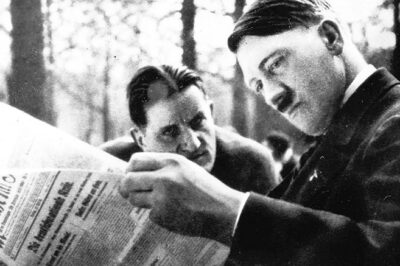

Putzi was close by Hitler’s side for the next decade and more and became his Foreign Press chief, dealing daily with the international media. Hitler was infatuated with Helene, and after dinner would occasionally lie on the sofa with his head on her lap as she stroked his hair. She considered him a ‘neuter’. Court historians dismiss Hanfstaengl’s role as of no significant historical importance. He was little more than Hitler’s piano player, a “court jester and buffoon” ready and willing to entertain him. William Shirer describes Putzi as “an immense, high-strung, incoherent clown” and “an eccentric with a shallow mind.”7 All part and parcel of the Establishment whitewash to conceal Hanfstaengl’s real background as a secret agent.

Putzi’s Role in the Reichstag Fire

On Hitler’s behalf on the night of the Reichstag Fire, the “shallow-minded, incoherent clown” was coordinating and deploying a team of highly specialised Nazi storm trooper arsonists. According to official accounts, Putzi was due to join Hitler and Goering for dinner at Goering’s house in Berlin that evening. Putzi relates in his ‘autobiography’ that he felt “shivery,” wanted to lie down, and phoned Hermann Goering with his apologies. President of the Reichstag, Goering, offered him a bed in the Reichstag president’s palace. The given reason for Putzi being in the palace on the night of the fire rings false, for he owned his own house in Berlin just minutes from the palace.

In all likelihood, Putzi went to the palace that night not because he felt “shivery” but to fulfil the massively important role of overseeing the burning of the Reichstag. How did a specialist team of arsonists with large quantities of flammable fuel gain access to the Reichstag without being seen? Only one door to the building was unlocked after 8 pm, and it was guarded throughout by security staff. Watchmen routinely toured the inside of the entire building just before it closed at 9 pm that evening and saw nothing untoward. No one could gain entry after 9 pm, and no one was seen to enter or leave.

The very reason Putzi was in the palace that night lay in the fact that unknown to all but a select few, an underground passage linked it to the Reichstag directly opposite. In Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, Professor Antony Sutton relates: “Hanfstaengl directed operations within the Palace, the propaganda apparatus stood ready, and the leaders of the Storm Troopers were in their places.… the scheme was almost perfect.”8 Under Putzi’s direction, the arsonists entered the Reichstag unseen via the tunnel, set multiple fires in the massive building, and returned via the tunnel to the palace. Putzi says he was asleep in the bedroom in the palace when the housekeeper rushed in shouting that the Reichstag was burning. He immediately phoned Goering and Hitler to inform them. In reality, he was calling to say, ‘Job done!’

Putzi & the Beer Hall Putsch

The Reichstag Fire was not the first time Putzi had been centre stage in Hitler’s violent attempts to seize power. Ten years earlier, a major event first brought the little corporal to national and international attention: the famous Beer Hall Putsch. On the bitterly cold evening of 8 November 1923, Hitler and Putzi stuffed pistols in their coat pockets and went to a meeting in the massive Burgerbrau beer keller in Munich. They stood drinking beer to the side of the crowd of 3,000 while the Bavarian State Commissioner, Gustav von Kahr, addressed his audience. 20 minutes into the speech, the audience was startled to hear the deep rumble of heavy trucks and clatter of hundreds of steel studded boots on the streets outside. Dozens of Nazi brownshirts burst in through the doors waving machine guns menacingly, while hundreds more sealed off the streets outside. Hitler handed Putzi his beer stein and, with his bodyguard at his back, strutted through the alarmed crowd towards the speaker. Jumping up on a chair, he silenced the crowd by firing his weapon into the ceiling and shouted: “The national revolution has broken out. This hall is occupied by six hundred heavily armed men. The Bavarian government and the Reich government are deposed. The police and army are now advancing under the banners of the swastika.”

He was lying. When he and his armed gang advanced down the road towards central Munich the following day, the police and army remained loyal to the government. Gunfire was exchanged with several police officers and 16 putschists killed and many wounded. Hitler was pulled to the ground, dislocating his shoulder. Extricated from the bloody scene by bodyguards, he was driven to Putzi’s farm at Uffing, an hour’s drive south of Munich. As prearranged, Helene was waiting there. She tended to Hitler and hid him in an attic bedroom. Putzi says he became separated from Hitler during the melee and escaped over the border into Austria.

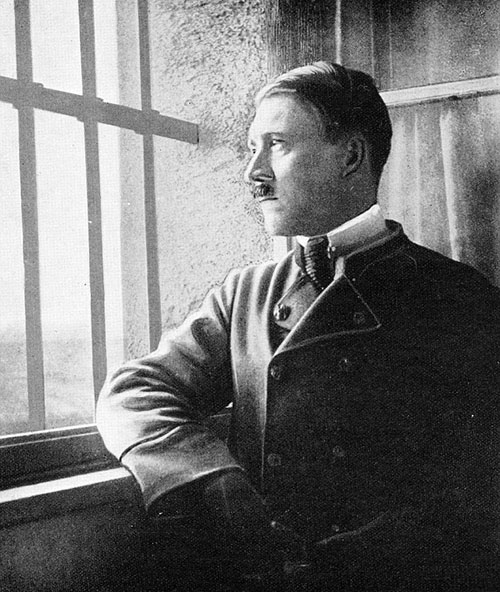

The following day, local police were tipped off, and several truckloads of officers duly arrived to arrest Hitler. He allegedly drew his pistol to commit suicide, and allegedly Helene grabbed the weapon. He was taken to Landsberg Prison and charged with high treason. The previously unknown Hitler made the headlines in newspapers across the world.

Putzi returned several weeks later but was never arrested or charged. He regularly visited Hitler in prison over the 11 months he served a five-year sentence. It was in Landsberg that Hitler wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle) in which he set out his political philosophy and anti-Semitic views. Several authors have suggested that Putzi played a significant part in the proofreading of Mein Kampf, if not indeed the writing. Hitler trusted him implicitly and they remained firm friends throughout his imprisonment. On release, his first port of call was to Putzi, Helene and Egon at their house in Munich.

In Reichstag elections held in December 1924, the radical right-wing parties picked up just three per cent of the votes, and the Nazis appeared to be a spent force. Inflation gradually came under control, bringing a much-needed period of stability to the ravaged country. Chastened by failure, Hitler decided to bide his time and attempt to gain power via the ‘democratic’ route. The Nazi party made little impact at elections over the 1920s, and Hitler entered his ‘quiet years’ at his comfortable home near the Alps. He and Putzi met regularly. During this quiet time, Putzi obtained a degree from Munich University with a thesis on eighteenth-century Bavaria. He was now Herr Doktor Hanfstaengl.

Extremely Dangerous Game

The Wall Street crash of October 1929 was music to the ears of Hitler, for he knew the German people would suffer badly as unemployment rocketed and look for radical solutions. “The Nazis could scarcely have hoped for a more propitious set of circumstances.”9 Hitler, with Putzi at his side, travelled by car or private plane campaigning in cities throughout Germany. As the economy disintegrated through 1930-32, the Nazis steadily gained votes and shared power in various coalition governments. Throughout that time, Putzi was making regular trips to London to meet Establishment figures who allegedly regarded Hitler with benevolence.

Even Lloyd George [Father of the House of Commons and former British Prime Minister] on whom I called, was no exception. He gave me a signed photograph to take back, on which he had inscribed: “To Chancellor Hitler, in admiration of his courage, determination and leadership.”10

This, as we shall see in part two, was part and parcel of the ‘appeasement’ game and duping of Hitler being played out by the British ruling class.

One evening on the campaign trail in Berlin, Putzi made excuses and slipped away for a meeting with an American journalist and secret service agent called John Franklin Carter. Carter came as an emissary from Putzi’s old friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt who was soon to become US President. FDR sent his warm greetings. Aware that Putzi was playing an extremely dangerous game on behalf of the Anglo-American elites and would be tortured and shot if Hitler uncovered the truth, Roosevelt warned him: “If things start getting awkward, please get in touch with our ambassador at once.” Putzi relates: “The message heartened me enormously, and in due course I would do just that.”11

In April 1932, Winston Churchill and his son Randolph – both friends of Putzi’s – visited Munich and invited him to dinner at their plush hotel. Churchill allegedly discussed the possibility of an Anglo-German alliance with him and was very keen to broach it with Hitler. Hitler, however, declined Churchill’s invitation to dinner. After a raucous evening with Putzi at the piano and the wartime British Minister singing, Churchill wished the Nazi’s success in the elections. Eleven months later, that success would come thanks to the Reichstag Fire.

Part two of this article, published in New Dawn 191, examines the major role played by Putzi’s masters – bankers on Wall Street and the City of London – in financing Hitler throughout the 1930s and building up the German war machine in preparation for the planned conflict with Russia. Franklin Roosevelt’s concerns for Putzi’s welfare became a reality in 1937, and he fled Germany for his life. Roosevelt takes him to Washington as a White House adviser, with a good salary, nice house, servant, and Steinway grand for his entertainment.

Footnotes

1. Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, 118

2. Guido Giacomo Preparata, Conjuring Hitler, How Britain and America Made the Third Reich, xvii

3. William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 30

4. Ernst Hanfstaengl, Hitler – The Missing Years, 36

5. Ibid, 14-16

6. Ibid, 51

7. Shirer, Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, 47

8. Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, 120

9. Peter Conradi, Hitler’s Piano Player, 77

10. Hanfstaengl, Hitler – The Missing Years, 212

11. Ibid, 188

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.