From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 7 No 3 (June 2013)

Thule people are the ones to whom Hitler first came.

– Rudolf von Sebottendorff

Rudolf von Sebottendorff (1875-1945) was a man of mystery. Much remains unknown about his life and his death. He is shrouded in legend and surrounded by misinformation. The true nature and motive of his life and work remain in question. That much of this obscurity was of his own manufacture is one thing that seems certain.

The first mystery of Baron Rudolf von Sebottendorff ’s life lies in the fact that he was not born a baron, nor was his name Sebottendorff. He obtained the name and title later in life. He was born Adam Alfred Rudolf Glauer in Hoyerswerda, near Dresden, on November 9, 1875. His father was a locomotive driver and veteran of the Prussian army, who fought in the Austro-Prussian campaign (1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (1871). Rudolf ’s father died in 1893 leaving enough money for his son to finish his formal education.

Glauer began training as a mechanical engineer, but never finished his studies. Instead he lived a life of adventure in exotic locales and on the high seas until 1900. In Australia, after attempting to prospect for gold, he received a letter of introduction from a Parsi (Zoroastrian) to a wealthy Turkish landowner, Hussain Pasha. He managed an estate at Bursa for this landowner, who was a practitioner of Sufism. He was also introduced there to the Termudi family. The patriarch of this Jewish family, originally from Greece, was a student of the Kabbalah and Rosicrucianism. Glauer was initiated into a Freemasonic lodge of which the Termudis were members. He remained in Turkey, learned Turkish, and studied occultism until 1902. Then he returned to Germany, but around 1908 some legal misadventures in Germany caused him to return to Turkey.

The next two years were pivotal for the adventurer. In 1910 he founded a mystical lodge in Constantinople – which is a tariqat of the Bektashi Order of Sufis. The next year he is legally adopted by the German expatriate Heinrich von Sebottendorff and also becomes a legal citizen of Turkey. This adoption was later repeated twice more by other Sebottendorff family members, all of which indicates just how important the acquisition of the noble title was to him.

During the Balkan War (1912–1913) he was on duty with the Red Crescent, the Islamic version of the Red Cross. He was actually wounded in battle and for a time a POW. After this he returned once more to Europe and lived in Berlin and Austria.

First World War

It was in the midst of the First World War (1914–1918) that Sebottendorff joined the Germanen Order (GO), at first by correspondence only. In September of 1916 he personally visited Hermann Pohl, who was the head of the order in Berlin. Subsequently Sebottendorff was elected master of the Bavarian province of the order and became the publisher of the GO publications.

The true nature and scope of the Germanen Order remains shadowy. Ostensibly it was formed as a sort of mystical lodge within the more politically oriented Reichshammerbund (Imperial Hammer League). The mastermind behind these groups was the notorious anti-Semite Theodor Fritsch (1852–1933).1 Fritsch was instrumental in the invention of a biologically based anti-Semitism to appeal to those who had become disenchanted with the mass appeal of the age-old religion based anti-Semitism, with its origins in the medieval church. The GO was essentially a pseudo-Masonic order with ritual based on Wagnerian imagery.2

As 1918 was drawing to a close, the fortunes of war and politics had turned against the Germans. The Great War was being lost and in Munich left-wing revolutionaries were clamouring for political power, inspired by recent success in the Russian Revolution (1917). The name Thule-Gesellschaft (Thule Society) was adopted by the Germanen Order as a cover identity (The word Thule comes from the Greek explorer and geographer Pythias, who made a journey to the far northern regions of the world around 310 BCE. He gave the name Thule to the land in the northernmost region.) The society met weekly in rented rooms at the Hotel Vierjahreszeiten (Four Seasons) in Munich. But it began to take on a life and identity of its own under Sebottendorff ’s leadership. Occult topics were the subject of lectures given by the baron – this in the midst of open revolution in the streets of Munich.

Sebottendorff only led the Thule Society from April 1918 to July 1919. During this time he formed a militia to fight the Communists, was instrumental in the formation of the German Workers’ Party, and acquired a newspaper, the Münchner Beobachter (Munich Observer). In April of 1919, Communists seized power in Bavaria. In this process they took seven members of the Thule Society hostage and subsequently executed them. This atrocity became a rallying point for the right-wing militias. The militias were eventually successful in turning back the left-wing revolution. The German Workers’ Party was soon thereafter reformed by charismatic leader Adolf Hitler into the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (National-Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Partei – NSDAP), called Nazis by their detractors. The newspaper was bought by that party and transformed into its mouthpiece – Der völkische Beobachter (The Nationalist Observer).

Obviously all of these facts point to Sebottendorff’s deep involvement with what was to become the Nazi movement in post-WWI Germany. It also seems clear that Sebottendorff and others were guided and financed in their efforts. What is less certain is how much these men were engineers of these efforts and how much they were mere pawns.

The chronology of Sebottendorff’s life shows that he was mostly involved in personal adventure and spiritual or magical pursuits – with a short, active career (1916–1919) as a political operative under the cover of occult organisations. After he left Munich in July of 1919, he returned to esoteric studies and writing. For fifteen years he continued in his esoteric pursuits and it is during this period that he wrote and published most of his major works, including, Die Praxis der alten türkischen Freimauerei (recently translated to English by this author and published as The Secret Practices of the Sufi Freemasons).

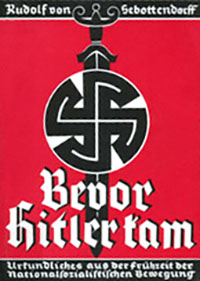

‘Before Hitler Came’

Astoundingly, Sebottendorff returned to Germany after Hitler took power in 1933, tried to revive the Thule Society, and published a book, which seemed to try to take credit for getting the National Socialist movement started from within the Thule Society. The book was entitled Bevor Hitler kam (Before Hitler Came). The Nazis were not pleased. Sebottendorff was arrested twice; the book was banned, confiscated, and destroyed in 1934. He returned to Turkey. This whole adventure appeared to be simply an attempt to cash in on the success of the Nazis, an attempt that failed. Or perhaps it did not fail entirely. The post-1934 life of the baron is quite mysterious. He was put on the payroll of the German Intelligence Service in Istanbul. His handler was Herbert Rittlinge. Turkey had been an ally of Germany in World War I, but in World War II it remained neutral until the very end of the war, when it joined the Allied side. In 1944 the German embassy was closed in Turkey, and Sebottendorff was given his severance pay of one year’s support. On May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered unconditionally. Sebottendorff died that same day.

Some controversy surrounds the death of Sebottendorff. The usual story is that he committed suicide by jumping off a bridge in Istanbul right after hearing of Germany’s surrender.

If this is true it was probably more out of the desperation of a septuagenarian man with no prospects for the future than out of any loyalty to the Nazis. On the other hand the possibility exists that he was assassinated either by loyal Nazis who wanted to keep him quiet, or by their enemies who took a final measure of revenge.

Works & Ideas

The life and legend of the adventurer known as the Baron Rudolf von Sebottendorff von der Rose is so fascinating and compelling that the more important and useful information about his teachings and thoughts are usually glossed over. We do not want to let that happen here. However, it must be admitted that discovering what the baron really thought can be a difficult task. This is because his did not write that much when compared to his contemporaries. Also what he wrote tended to be from different genres – for example, novels, histories of astrology, technical astrological texts, and the book on Sufi exercises.

When we look at Sebottendorff’s written output we discover that most of it concerned aspects of the practice of astrology. His works include: Die Hilfshoroskopie (1921), Stunden- und Frage-Horoskopie (1921), Sterntafeln (ephemeriden) von 1838–1922 (Star Tables [Ephemeris] from 1838 to 1922) (1922), and Astrologisches Lehrbuch (Astrological Textbook) (1927). Perhaps to be counted as his masterpiece in astrological studies is Geschichte der Astrologie (History of Astrology), vol. I (1923). No second volume appeared. Besides these astrological works, three others stand out.

The first of these is Die Praxis der alten türkischen Freimauerei (1924). Second is a novel, Der Talisman des Rosenkreuzers (The Talisman of the Rosicrucian) (1925). This is said to be a thinly veiled autobiographical account from which many events in his life are discernible. Finally there is the ill-fated Bevor Hitler kam (1933). The latter two books are in one way or another attempts to manipulate the reader’s views of the author. Only in the Praxis does Sebottendorff really speak to the reader about his own philosophy – if only vaguely.

Sebottendorff, the man, remains an enigma. Some of his writings were probably produced to achieve some specific political agenda that was not necessarily a creation of his own thoughts. However, if we read his words carefully we can arrive at some general ideas about the intellectual and spiritual cosmos in which he lived. In many respects Sebottendorff was the typical German of his time – a man with a split character: one part fierce nationalist, the other a lover of the exotic. In Sebottendorff’s lifetime he had reason to be proud of being German – Germans were the best educated, most technologically advanced and economically developed of all European peoples. At the same time they loved exotic ideas and exotic cultures; they studied them, and travelled to them at an enormous rate. Even now, more Germans travel outside their own borders per year than any other nation, and it is no coincidence that the German word wanderlust, “a strong and irresistible impulse to travel,” had to be borrowed into English.3 All this accounts for Sebottendorff’s German nationalism coupled with his love of Turkey. To understand his ideology, we must divide the political dimension from the occult aspect; although we will see some common ground between the two.

Political Ideology

Most of Sebottendorff’s written output would not indicate much of an interest in politics. It is far more oriented toward occult matters. However, both his biography and one book in particular, Bevor Hitler kam (1933), show his involvement in founding and directing insurgent political operations. Where and how he came by these skills and interests remain mysterious.

In introductory sections of his 1933 book he describes his devotion to two ideas Deutschtum (Germanism) and socialism. The idea of Deutschtum had been current in Europe for many decades.4 On the one hand it can be understood as simply nationalism. But German nationalism, as with other forms of this idea elsewhere in the Old World, is heavily tinged with racial ideas. German (or English or French or Russian) nationalism meant more than fanatically supporting a political state. It meant a belief that the culture of the nation, its language, ethnicity, customs, and aesthetics, were to be promoted to the exclusion of foreign or outside elements. It also was bound up with concepts of antimodernism. Antimodernists saw industrialisation, commercialism, and democracy as destructive to the nation and to Deutschtum.

To some extent these ideas were rooted in the esoteric teachings of men such as Guido von List (1848–1919) who coined and popularised a good deal of the terminology connected with this idea. Clearly Sebottendorff was steeped in the teachings of von List and others. But he was far from being alone in this. In fact List was himself merely another product of a larger neo-Romantic wave of ideology championed by Richard Wagner and others decades earlier.

The other political idea that moved Sebottendorff was socialism. Mainstream historical revisionism quickly moved to ignore the socialistic aspects of Hitler’s National Socialism. It really should not be surprising therefore to see immediate precursors to Hitler extolling the idea of socialism, which most today think of in terms of left-wing politics. The essential theoretical factor that separates Hitler from Stalin was that the former saw biology or race as the decisive factor, while the latter saw economics and economic class as paramount. In practice, however, both essentially practiced nationalistic socialism under a dictatorship or oligarchy.

Certainly Sebottendorff, like many of his German and European contemporaries, envisioned a kinder and gentler form of socialism; one that wisely and benevolently collected the wealth and privilege of the nation and redistributed it to the benefit of the whole of society. Such dreams always lead immediately to a Hitler or Stalin, when applied on a national scale. National socialism would attempt to apply socialistic concepts and methods to the benefit of a single race or nationality – the Germans – rather than to an economic class – the proletariat – as is the case with the Marxists.

Occult Ideology

The occult encompasses ideas of a secret or hidden nature, which represent rejected patterns of thought (e.g., paganism, astrology, alchemy, magic) or concepts that have not been accepted by mainstream and established intellectual authorities (e.g., UFOs, ESP, orgone). Such ideas may be entirely taboo in a society and forced into secret societies, or they may simply be marginalised. Despite its outsider status the realm of the occult often becomes the breeding ground for revolutionary ideas.

Sebottendorff’s occult ideology can be partially reconstructed from his works. One factor of great importance to him was a sort of unified field of reality that connected things such as the stars with the fate and character of individual humans. Here we see an echo of the Islamic insistence on the essential unity of being (the Arabic wahdat-al-wujûd). This also provides Sebottendorff with the rationale for his focus on tradition and national traditions – whether in Germany or Turkey. Such a unity of being also provides for the plausibility of alchemy. The base and the noble are, after all, parts of the same whole, or substance. Therefore the transmutation of one thing to another is theoretically possible, without changing the nature of reality.

One of Sebottendorff’s chief themes is the idea of the perfectibility of the individual. This is the root concept behind the exercises belonging to the science of the key, as the ancient practice of Freemasonry is sometimes known. The fruits of this labour should, however, be transferred to the larger society in which the individual lives and this doctrine of perfectibility spread throughout the country. The individual can, in a manner of speaking, become something akin to a philosopher’s stone. His presence can act as a catalyst for widespread transformation. Is this the secret of Sebottendorff? So much power and influence has been ascribed to him, yet the facts of his life do not reflect such a man. How could a relatively unknown occultist and adventurer exert such historical influence and fade from the scene years before the results of his operation were manifest? Why then did he come back to make a conspicuous return at the moment of the operation’s dark triumph, before once more fading into obscurity?

Certainly another of Sebottendorff’s principal ideas was that individuals are capable of creating and re-creating their own environment. This concept was juxtaposed to the modernistic idea that individuals are products of their environments. All of this again brings forth Sebottendorff’s essentially magical and alchemical view of man’s capacity. The human being, and especially the individual who has been empowered by the secret practices revealed in the science of the key, can take active control of life and environment – but only in accordance with the will and direction of God.

Abridged with permission from Chapter 1 of Secret Practices of the Sufi Freemasons: The Islamic Teachings at the Heart of Alchemy by Baron von Sebottendorff (translation & Introduction by Stephen E. Flowers, Ph.D.). Inner Traditions, Rochester, VT 05767 USA. This book is available from all good bookstores or visit www.InnerTraditions.com.

Footnotes

1. For more information on Theodor Fritsch, see Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism, 123-28

2. A historical description of the Germanen-Order is provided in Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism, 123-34

3. See The American Heritage Dictionary (1975), s.v. “wanderlust.”

4. The whole topic of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Germanentum, especially in esoteric circles, is discussed by Goodrick-Clarke, The Occult Roots of Nazism.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.