From New Dawn 188 (Sept-Oct 2021)

In 1959, while staying at the farmhouse of an old friend, the British existentialist Colin Wilson came across a book seemingly designed to attract his attention; the fact that it was the only one in the house practically ensured that it would. Its title was The Outsider and Others and its author was H. P. Lovecraft, the American pulp horror fiction writer from the pages of Weird Tales, who in recent time has been promoted to the rank of a Penguin Modern Classic. Wilson had never heard of Lovecraft but his own first book, the one that had made his name as an “angry young man” a few years back, was called The Outsider, so naturally he was interested.

Wilson’s book was an account of modern alienation and the extreme mental states of creative individuals trying to overcome it. Lovecraft’s brand of “eldritch,” “grotesque,” “nameless” horror – these are only a few of his hyperbolic adjectives – seems far away from the angst and la nausée of existentialism, and yet appearances can be deceiving. Wilson took the mouldy volume off the shelf – it was published in 1939, two years after Lovecraft’s death – its yellowing pages almost crumbling at his touch, and settled down to read. Before turning in that night Wilson knew that he had come across an “outsider” indeed. If anyone fit the bill of the isolated, alienated man of genius, loathing the mediocrity of the modern age, Lovecraft did.

Wilson was so taken with Lovecraft that reading him inspired one of the books in his “Outsider Cycle,” in which he attempts to provide the foundation of what he called a “new existentialism,” to replace the dreary rive gauche version of Sartre and Camus, and the gloomy Schwarzwald meditations of Professor Heidegger.1 Wilson believed that all three had taken a wrong turn at Edmund Husserl, the founding father of phenomenology, out of which existentialism emerged. The books in Wilson’s “Outsider Cycle” methodically spell out his objections to what had become a philosophy of meaninglessness and despair, in an attempt to regain existentialism’s original object: the vision of freedom. In outsider figures like Blake, Nietzsche, Gurdjieff, and others, Wilson had discovered experiences of a “Yea-saying,” affirmative consciousness that Sartre and the others had left out of their analyses. Central to his analysis of these moments of “affirmation” was Husserl’s dictum that consciousness is intentional. It is not the passive recipient of sense impressions impinging from without, but an active reaching out to reality, in order to grab it with the talons of the mind. It was this, Wilson believed, that the old existentialists had lost sight of.

Wilson’s book, The Strength to Dream (1962), a study in what he called “existential criticism,” focused on how different writers used the imagination to present their values, their vision of the world. He started with Lovecraft and were he alive to have read it – which is entirely possible; he would only have been in his early seventies – Lovecraft would no doubt had been gratified that he was taken seriously, and perhaps not a little bemused at the literary company he was keeping. Wilson put him in the context of W. B. Yeats, August Strindberg, and, perhaps surprisingly Oscar Wilde, as agents of what he called “The Assault on Rationality,” writers who reject the everyday world and create an alternative more to their liking. Yet Lovecraft might not have been amused at Wilson’s assessment of him as “that man of dubious genius” who “carried on a lifelong guerrilla warfare against civilisation and materialism,” and who was a “somewhat hysterical and neurotic combatant.”2

Aside from his atrocious style, filled with phrases like “black clutching panic” and “stark utter horror” – Lovecraft always had a bad habit of overwriting – what repelled Wilson about Lovecraft was his “soured romanticism.” He was a man so revulsed by the triviality of modern life, it seemed, that he reminded Wilson more of the Düsseldorf mass murderer Peter Kürten, who dreamed of blowing up whole cities, in fantasies of revenge against the inequities of life, than of his tragic predecessor, Edgar Allan Poe.3 Lovecraft never engaged in any of the violent acts that filled Kürten’s horrific career, but his tales of ancient evil and exiled gods – Cthulhu and Co. – returning to their lost domain – planet Earth – were, Wilson believed, the literary and psychological equivalents of Kürten’s brutal assaults on “society.” Both, Wilson argued, were engaged in acts of ressentiment against a world that negated them.

Wilson’s estimation of Lovecraft, however, increased over time, helped by a visit to Providence, Rhode Island, where Lovecraft spent most of his short life. Wilson was a visiting lecturer at Brown University and took the opportunity to read Lovecraft’s letters and other works held in the library. His interest eventually led to a correspondence with August Derleth, the man more than anyone else responsible for Lovecraft being known at all today. After Lovecraft’s death Derleth became his literary executor and through his Arkham House Press kept Lovecraft in print. Derleth had read Wilson’s criticisms of Lovecraft and thought he had been unfair. Wilson was open enough to Derleth’s comments to revise some of his remarks about Lovecraft for the American edition of the book. Yet Derleth still felt Wilson had short changed Lovecraft. In a letter to Wilson he wrote, “If you’re so critical of Lovecraft, why don’t you write a fantasy novel, and see whether it’s any good…”4

Wilson Takes Up the Challenge

Not one to ignore a challenge, Wilson brooded on the idea. His interest was not in terrifying people as Lovecraft’s had been. It was, in fact, more along the lines of the sort of quasi-science fiction Lovecraft was writing towards the end of his life, in stories like The Shadow Out of Time. With its vision of ancient alien races sending their consciousness out into the depths of time and space, this produces more a sense of awe than a shudder – something we find in H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon, two other writers with a “cosmic” point of view. Wilson’s own vision was that of a consciousness free from time, able to rise above the “triviality of everydayness” that revulsed Lovecraft (the phrase is Heidegger’s) and become aware of the “reality of other times and places,” and not only of the one in front of your nose.

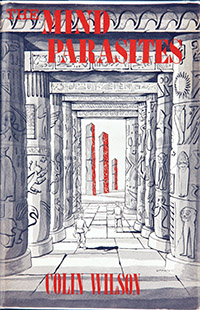

It was while working on his Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966)that Wilson came upon an idea that would give the old Lovecraftian theme a new twist. Lovecraft’s fellow Weird Tales writers all added to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, inventing gods, ancient races, lost cities, and, most effectively, fictional texts such as Lovecraft’s Necronomicon, that give the tales a flavour of authenticity. But Wilson’s contribution wouldn’t be another god, like Clark Ashton Smith’s Tsathoggua, although he will draw on this, nor a forbidden text like Robert E. Howard’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, nor will his protagonists meet their doom in a ruined temple on some unknown South Pacific island. Wilson’s monsters would come from somewhere else. They would come from the mind.5

Wilson’s first foray into what we can call “phenomenological science fiction,” The Mind Parasites (1967), came on the back of a series of novels in which Wilson used the constraints of genre fiction for philosophical purposes.6 His first novel, Ritual in the Dark (1960), is an existential thriller about a sexual killer, and could best be described as Jack the Ripper meets the Brothers Karamazov in duffle-coated early 1950s London. It works out in fictional form some of the themes of The Outsider. This was a practice Wilson continued with detective novels (Necessary Doubt (1964)), psychological crime thrillers (The Glass Cage (1966)), erotica (The Sex Diary of Gerard Sorme (1961)), and later with espionage, police procedural, soft porn, and, as we will see, science fiction.

Wilson’s engagement with Lovecraft led to several works, some serious attempts at using Lovecraft’s themes for philosophical purposes, some, like his contributions to the Lovecraft sendups The Necronomicon (1978) and The R’lyeh Text (1995) more tongue in cheek pastiche than anything else.7 The two novels I look at here, The Mind Parasites and its follow-up The Philosopher’s Stone (1969), are Wilson’s masterpieces in the genre. In them Wilson managed to put into gripping fictional form the essence of his “new existentialism,” and the insight that would inform his decades long investigation into the occult and paranormal, his search for “Faculty X,” the ability of the human mind to free itself of the constraints of time and space and occupy “other times and places.”

Wilson wrote another science fiction novel, The Space Vampires (1976), that uses some Lovecraftian ideas – sadly it was made into the dreadful film Lifeforce (1984) – and his later epic Spider World series(1987-2002)is his attempt at a Tolkienesque fantasy. Yet it is in The Mind Parasites and The Philosopher’s Stone that Wilson managed to find, to my mind at least, the perfect balance between the ideas and a narrative to convey them. The books are, borrowing a title from Alfred North Whitehead, “adventures of ideas.” Like the late novels of H.G. Wells, that Wilson, against critical opinion, rated highly, they are compelling because of Wilson’s ability to make the ideas come alive. The reviewer who said of his work that he had a “narrative style that can make the pursuit of any idea seem exciting detective work” knew what he was talking about.

The Mind Parasites

The Mind Parasites begins in 1994 – the future for its first readers, the past for us – when the archaeologist Gilbert Austin learns that his friend, the psychologist Karel Weissman, has committed suicide. The death, of course, was enough to shock him. But suicide? “It was impossible.” Weissman “had not an atom of self-destruction in his composition.” What could have driven him to take his own life? It was true that the suicide rate had increased considerably over the years. But Weissman was a follower of the humanistic psychology of Abraham Maslow (who shares billing with Husserl in the new existentialism). It was unthinkable. What made him do it?

The answer to that, Austin suspects, could be found in the collection of papers Weissman left behind. Yet before Austin can attend to them, his own work takes him to Turkey where he and his colleagues make an incredible discovery. Strange figurines of an unknown origin lead them to tunnel below the surface only to discover a huge block seventy feet long two miles underground. It is the remains of a cyclopean city, a metropolis built by giants eons ago…

Yet these allusions to the Great Old Ones and Elder Gods of Lovecraft’s mythos are really a red herring, for the truly evil creatures – who, borrowing from Clark Ashton Smith, Wilson calls the Tsathogguans – are not, like Cthulhu, resting in sunken R’lyeh, waiting to be awakened, but inhabit a much more intimate space: that of the mind. Austin discovers why his friend had killed himself: he had become aware of psychic vampires that have been bleeding human consciousness dry for the past two centuries, and they had got rid of him… Just as they had got rid of the generation of creative geniuses, the Romantics, who Wilson sees as the first sign of a new stage in the evolution of human consciousness.

Wilson’s The Outsider sought to answer the question why so many creative individuals of the 19th and early 20th centuries either died young, went mad, committed suicide, or in some way came to a bad end. Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Ibsen, Keats, Shelley, Kleist, Novalis, Poe; this list, chosen at random, could go on. These men and others, lesser known, experienced eruptions of the imagination unlike anything that had been seen before. The poets of the previous age said that the “proper study of man is man.” The Romantics disagreed and sought to embrace the entire universe. The ecstasies they experienced convinced them that men were really sleeping gods. Yet when they returned to earth from their ecstatic excursions, they were struck by the banality of the world they were forced to inhabit, and their inability to revive the vision of inner freedom and space, the “bird’s eye view” over space and time. Self-pity, depression, weariness set in. Baudelaire compared the poet to the albatross: when aloft, the bird’s great wings enable him to soar gracefully, yet on land they are encumbrance, tripping him up. This brutal world was not meant for such noble creatures, and so many of them succumbed.

Wilson’s mind parasites are an allegory of how the mind can collapse on itself, of how easy it is for it to slip into existential despair and a self-produced insanity. In The Outsider Wilson relates several experiences of what Swedenborg called “vastation,” a total emptying out of any sense of meaning, of any reality propping up your existence. One night on the desert, meditating on the reality of history, and on the knowledge of that reality housed within his mind, Gilbert Austin becomes aware that within his own consciousness, there is a universe as strange and unknown as the one he gazes out on at the stars… the essence of the Romantic vision. It was then that something odd happens. Austin catches a glimpse of “some alien creature” in his own mind. He then discovers that his friend Weissman had had the same experience. Weissman’s research into the growing suicide rate uncovered a disturbing fact: the human race was losing its power of self-renewal. “For more than two centuries now,” Weissman reports, “the human mind has been constantly a prey to energy vampires.”

Around the turn of the eighteenth century, a kind of change came over the western mind: the powerful optimism of the early Romantics – Beethoven, Goethe, Blake – is followed by a gloomy pessimism, a despair the mind parasites feed on. “The artists who refused to preach a gospel of pessimism and life-devaluation were destroyed.” Some individuals, like the Marquis de Sade, were completely in the vampires’ control. Pessimists, like Schopenhauer, lived to a ripe old age. Nietzsche, the life-affirmer, goes mad. Men may really be gods, but it is in the parasites’ interest that they never find this out. Those who suggest as much are quickly done away with…

Having become aware of the parasites, Weissman is a threat to them, so they attack him with waves of depression and despair until he can stand it no longer and kills himself. When the parasites discover that Austin is aware of them, they try the same tactic. But in the meantime he has learned of Husserl’s work in phenomenology and of the central insight that consciousness is intentional. In one of the most remarkable battle scenes in all literature, a campaign that takes place entirely within the mind, Austin fends off the waves of suicidal emptiness and cosmic despair until his increased powers of intentionality rout the parasites.8 Now that their cover is blown, it is all out war.

The rest of the novel relates Austin’s gathering together a team of other intellectuals – psychologists, historians, scientists – who become the human race’s vanguard against the parasites. Through mastering Husserl’s phenomenological techniques, they learn how to direct their intentionality as if it were a laser beam of consciousness. One by-product of this is that they all become psychokinetic, their consciousness able to reach out and “grab” the world in a very literal way. Their psychokinetic powers are enormous. In an attempt to unite the world against the parasites, they use their combined mental energies to disintegrate the “Kadath block” on live television, claiming it was destroyed by the parasites. When they discover that the parasites have a base on the moon, they decide the only way to rid humanity of these deadly pests is to move the moon out of its orbit. Wilson’s use of the moon as the source of mankind’s afflictions is a nod to Gurdjieff, who saw “sleeping humanity” as “food for the moon.” He also makes use of the theories of Hanns Hörbiger, enamoured by Hitler, about the different moons the earth has had in the past.

By the end of the novel, not only have Austin and his colleagues got rid of the moon, they have fended off a race war, prompted by the parasites, who glut themselves on the negative energies given off. The discovery of the ancient cyclopean city that started the book is of relatively minor importance compared to the revelatory insights into consciousness the team has achieved. At one point in the story, Austin becomes aware of other intelligences, benevolent ones, out in space, beyond the orbit of Pluto. He and his colleagues ride off, not into the sunset, but in the direction of that distant planet, their spaceship propelled by the powers of their minds… They are eager to join the other “policemen of the universe,” and to learn exactly how powerful a consciousness free of the parasites really is. Their mysterious voyage becomes a myth for future exploration into the vastness of existence, inner and outer.

The Philosopher’s Stone & Relationality

In The Mind Parasites Wilson explores the possibilities inherent in Husserl’s intentionality. In The Philosopher’s Stone it is another power of consciousness, relationality, Wilson’s own coinage, that takes centre stage. Readers of Wilson’s little book Poetry and Mysticism (1968), written at the behest of the poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti for his City Lights imprint, will recall that in it Wilson’s speaks of “duo-consciousness” and of what he calls the “web-like” character of consciousness, when thoughts and recollections spread out and link together, forming a kind of “net” of awareness. In The Philosopher’s Stone the relationality of consciousness leads to what Wilson calls “time-vision,” the ability to look into the past as if through a telescope. If in The Mind Parasites the heroes discover their psychokinetic powers, in The Philosopher’s Stone it is psychometry, the ability to know the past of an object simply through touch, that Wilson’s heroes discover they possess. It is through this that the protagonists become aware of the Great Old Ones, brooding in some dimension outside our own, waiting for their chance to return…

But again, they are a red herring. The real subject of the novel is once again consciousness; this time, its potential to slow down and even to stop the aging process. In Back to Methuselah, Bernard Shaw argued that human life is too short to make any good use of it; humans needed to live to at least three hundred in order to mature. Wilson took up Shaw’s challenge as to how this could be done. His answer: the fountain of youth – or at least of immortality – lay in the prefrontal lobes of the brain.9

In search of a phenomenological elixir vitae, Wilson’s hero, Howard Lester, discovers that the “value experiences” of the psychologist Aaron Marks (Maslow’s “peak experiences”) seem able to slow down our biological clocks. He arrives at this insight after his research leads him to conclude that, statistically, philosophers, composers, scientists, mathematicians – anyone who makes a practice of trying to view life objectively, and not through the gauze of their emotions – live longer than other people. He discovers that the source of the “VE” are the brain’s prefrontal lobes, its most evolutionarily advanced part. Through a series of experiments introducing a minute quantity of “Neumann alloy” into their own prefrontal lobes, Lester and his colleague, like Gilbert Austin and his team, discover unknown powers of consciousness. Their “relationality,” the intuitive glue that spreads across reality like the ripples on the surface of a deep, still pond, increases enormously, until they are able to use their imagination to peer into time.

Wilson has a long section in which Lester, sinking into a state of “contemplative objectivity,” finds himself in sixteenth century London, rather as Charlotte Ann Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain, authors of An Adventure (1911), found themselves transported to the Versailles of Marie Antoinette. This is a time travel novel with a twist. Actual, physical time travel, the kind his hero H. G. Wells wrote about in The Time Machine, Wilson argues, is an absurdity. There is no “time” to travel through; “time” is a word we use to refer to process, and to think of “process travel” is nonsense. But the mind is not limited by the logic that constrains physical reality, as J.W. Dunne, author of An Experiment With Time (1927), discovered with his “precognitive dreams.” Just as Dunne was able to see into the future, Wilson’s phenomenological alchemists, in search of their own philosopher’s stone, can turn their vision to the past. The imagination, Wilson said, is “the ability to grasp realities not immediately present.” The past isn’t present, but it is a reality, and through their increased powers of relationality – awareness of the connectedness of everything – Wilson’s heroes can imaginatively grasp it.

One result of this new faculty is proof that Francis Bacon was really the author of Shakespeare’s plays. Another is that K’ tholo – Lovecraft’s Cthulhu – was one of the founders of human civilisation. Another is that the Great Old Ones are not dead, only sleeping, but their influence can be felt. They have erected barriers to the heroes’ time-vision which prevents them from reaching far enough back into the past to solve the mystery of… but that would be telling. En route the reader learns the truth about Stonehenge, the Maya, the Voynich Manuscript – a Wilsonian standby, that surfaces in more than a few places – poltergeists and much more.

Wilson said that the aim of his writing was to get people to think. His novels are more fables or parables, than the kind of character analysis we associate with most modern fiction, which sticks obsessively to “everyday” consciousness and its trivial concerns. They share this character with the late novels of Wells, which use the barest structure of a novel for didactic purposes. Readers who find ideas exciting will find Wilson’s – and Wells’ – didactic fictions breath-taking. (“I apologise for sounding didactic,” Wilson’s hero says at one point. “It is impossible to say anything that is not commonplace without sounding didactic.”) I have read them a number of times yet each time I discover new things and come away exhilarated. If, as Wilson says, “close-upness deprives us of meaning,” his phenomenological fictions are cable cars to the heights, to the “bird’s eye view,” that enables us to enter that inner universe from which we can view the outer one with “contemplative objectivity.” “The will feeds on enormous vistas,” Wilson tells us. “Deprived of them, it collapses.” In The Mind Parasites and The Philosopher’s Stone the reader will find vistas enormous enough to feed his will no end.

Footnotes

1. The Outsider (1956), Religion and the Rebel (1957), The Age of Defeat (The Stature of Man in the US) (1959), The Strength to Dream (1962), Origins of the Sexual Impulse (1963), Beyond the Outsider (1965), and Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966).

2. Colin Wilson, The Strength To Dream (London: Abacus, 1979) p. 1.

3. Colin Wilson and Pat Pitman, Encyclopedia of Murder (London: Arthur Baker, 1961) pp. 326-335.

4. Colin Wilson, The Mind Parasites (Rhinebeck, NY: Monkfish Press, 2005) p. xvii.

5. Wilson admits to being inspired by the science fiction film Forbidden Planet (1956), in which Walter Pidgeon portrays Morbius, a scientist who has increased his mental powers through contact with the technology of an ancient, more highly evolved race. He was unaware that he was at the same time increasing the power of his unconscious mind. Because of this he releases “monsters from the Id.”

6. Recently the book has been the object of some renewed interest, seeing Wilson’s allegorical creatures as the possible agents of our contemporary malaise. See www.awakeninthedream.com/articles/mind-parasites-of-colin-wilson

7. Wilson also contributed two shorter works, “The Return of the Lloigor,” in Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos, ed August Derleth (Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 1969) and “The Tomb of the Old Ones” in The Antarktos Cycle, ed Robert M. Price (Oakland, CA: Chaosium Publications, 1999).

8. I can only mention here that in another novel, The Black Room (1971), an espionage tale set around the effort to defeat a sensory deprivation chamber, Wilson works out the same ideas.

9. This was before Wilson became aware of the significance of “split brain” psychology surrounding the left and right cerebral hemispheres, which he will write about in Frankenstein’s Castle (1981) and Access to Inner Worlds (1983).

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.