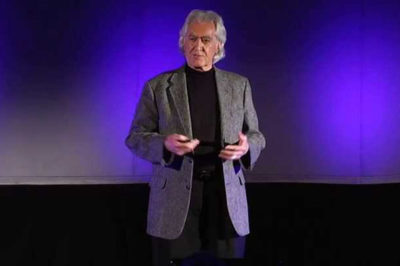

When Larry Dossey was in his first year of medical practice, he experienced a week of premonitions about patients, all of which came true. He later became intrigued by patients who were blessed with “miracle cures,” remissions that clinical medicine could not scientifically explain.

Searching for an understanding of the interaction between mind, body and spirit, Larry Dossey embarked on a life-long study of religion, philosophy, meditation, oriental literature, parapsychology and quantum physics.

Today, he is a respected leader in bringing scientific understanding to spirituality and an internationally influential advocate of the role of spirituality in healthcare and wellness.

During his distinguished career as a practitioner of integrative medicine, he helped establish the Dallas Diagnostic Association and served as Chief of Staff of Medical City Dallas Hospital. The author of eleven books, including the New York Times bestseller Healing Words, he is executive editor of Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing.

Dr. Dossey has lectured all over world and at major medical schools and hospitals in the United States – Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Cornell, and the Mayo Clinic, among others. A native Texan, he lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

In the following interview, Dr. Dossey introduces his latest book The Power of Premonitions: How Knowing the Future Can Shape Our Lives, taking readers through documented cases of premonitions, an examination of recent science, and practical techniques for inviting premonitions.

What’s your book about?

Larry Dossey (LD): Premonitions – knowing what’s about to happen.

What’s a premonition?

LD: “Premonition” literally means “forewarning.” Premonitions are a heads-up about something just around the corner, something that is usually unpleasant. It may be a health crisis, a death in the family, or a national disaster.

But premonitions come in all flavours. Sometimes they provide information about positive, pleasant happenings that lie ahead – a job promotion, where the last remaining parking place is, or, in some instances, the winning lottery numbers.

A favourite example of yours?

LD: Amanda, a young mother in Washington State, was awakened one night by a horrible dream. She dreamed that the chandelier in the next room had fallen from the ceiling onto her sleeping infant’s crib and crushed the baby. In the dream she saw a clock in the baby’s room that read 4:35, and that wind and rain were hammering the windows. Extremely upset, she awakened her husband and told him her dream. He said it was silly and to go back to sleep. But the dream was so frightening that Amanda went into the baby’s room and brought it back to bed with her. Soon she was awakened by a loud crash in the baby’s room. She rushed in to see that the chandelier had fallen and crushed the crib – and that the clock in the room read 4:35, and that wind and rain were howling outside. Her dream premonition was camera-like in detail, including the specific event, the precise time, and even a change in the weather.

Why are premonitions about unpleasant things? Why don’t we have premonitions about winning the lottery, the right stocks to pick, or when to bail out of the stock market?

LD: Most researchers believe premonitions are trying to do us a favour. They are mainly about survival. If you know that something life-threatening is approaching, you have a chance to avoid it. This would increase your chance of staying alive and reproducing – our evolutionary imperative. That’s probably why premonitions are often about threats to our existence, why they have become built into our biology, and why probably everyone has a premonition sense to some degree.

Why did you write this book?

LD: I actually tried not to write it. I largely ignored this stuff for years, but this didn’t work very well. My own experiences of premonitions grabbed me and wouldn’t let go.

During my first year in medical practice as an internist, I had a dream premonition that shook me up and made me realise the world worked differently than I had been taught.

Briefly, I dreamed about a detailed event in the life of the young son of one of my physician colleagues. It turned out to be so accurate it scared me. There was no way I could have known about the event ahead of time.

Then patients of mine began telling me about their own premonitions. Even my physician colleagues would occasionally open up and share their premonitions with me. So I decided this was a well-kept secret in medicine that needed telling.

The time is right for this book because science has come onto the premonitions scene. There are now hundreds of experiments that confirm premonitions, which have been replicated by researchers all over the world.

So there’s a new story to tell. It’s no longer only about people’s experiences, but it’s also about science. Many people still think this stuff is just mumbo-jumbo and that there’s no science to back it up. It’s the “everybody knows” argument – “everybody knows” you can’t see the future, so proof of premonitions cannot possibly exist.

That’s wrong. We now know we can see the future, because that’s what careful scientific studies show.

If people can see the future, why don’t they get rich playing the stockmarket?

LD: Some do. Bill Gates says, “Sometimes, you have to rely on intuition.” Oprah Winfrey says, “My business skills have come from being guided by my inner self – my intuition.” Donald Trump says in The America We Deserve, “I’ve built a multibillion empire by using my intuition.”

George Soros, the billionaire investor, has all sorts of theories to back up his decisions. But according to his son, “At least half of this is bull… [T]he reason he changes his position on the market or whatever is because his back starts killing him. He literally goes into a spasm, and it’s this early warning sign.”

Researchers have tested CEOs of successful corporations for their ability to see the future, such as predicting a string of numbers they will be shown later. The CEOs who are good at this are usually those who are also highly successful in running their corporations. In other words, their precognitive ability correlates with their corporate success. CEOs who did not have this ability tend to have mediocre success rates in their corporations. So business success and premonition ability seem to go hand in hand.

In one study, experimenters were able to predict in advance the most successful corporate balance sheets by how well the CEOs did on tests that measured their ability to predict the future, such as a string of numbers they’d be shown later.

This ability was not dependent on reason or logic or inference. You can’t “reason” and “analyse” what a randomly chosen string of numbers is going to be.

Interestingly, these CEOs were shy about owning their premonition sense. They didn’t call their abilities premonitions, but good “business sense.” The polite word for premonitions in business is “business intuition.” There’s a growth industry in teaching business intuition. Google “business intuition” and you’ll come up with nearly a half million hits.

Do premonitions work for people in business who are not CEOs?

LD: Yes. I discuss several experiments in which people used their premonitions to make large sums of money in the silver futures market. One of these experiments was featured on the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

So what keeps people from getting rich?

LD: The limiting factor seems to be greed. When the subjects focused on making modest sums of money, the experiments worked; when they got greedy and tried to break the bank, the experiments flopped.

This reminds us of what happened on Wall Street beginning in the fall of 2008. Nearly all the pundits say the primary underlying reason for the crash was unbridled greed.

You talk about “evidence” for premonitions. But isn’t the evidence just anecdotes and people’s stories?

LD: This field used to be only about stories, but that’s changed. There’s now a science of premonitions. For the first time in history, we can now use “premonition” and “science” in the same sentence.

Take the “presentiment” experiments that have been pioneered by consciousness researcher Dean Radin. Briefly, a person sits in front of a computer, which will make a random selection from a large collection of images that are of two types – calming or violent. Calming images may be a lovely scene from nature; violent images deal with death, carnage, grisly autopsies, and so on. The subject has some physiological function being measured, such as the electrical conductivity of the skin or the diameter of the pupil. The bodily function begins to change several seconds before the image is randomly selected by the computer and shown on the screen. Here’s the shocker: the physiological change occurs to a greater degree if the image to be shown is violent in nature. How is this possible? How does the body know which image is going to be shown in the future?

Dozens of these studies have been done by various researchers. They show that we have a built-in, unconscious ability to know the future. Somehow the body knows before our awareness kicks in.

There’s a charming quotation in the book The Secret Life of Bees that captures this. Fourteen-year-old Lilly says, “The body knows things a long time before the mind catches up to them.”

Another type of experiment is called “remote viewing,” in which people can consciously know highly detailed information up to a week before it happens. These studies were pioneered at Stanford Research Institute and have been replicated at Princeton University and elsewhere.

How can we know when to take a premonition seriously?

LD: If the premonition is about your health or if it involves images of death, it’s wise to take it seriously. You might not get a second chance.

A patient of mine had a dream premonition of “three little white spots” on her left ovary. She feared this meant she had ovarian cancer. We checked it out. Her sonogram showed she was accurate; she indeed had three little “white spots” on her left ovary, but they were benign ovarian cysts, not cancerous. She did the right thing; she had a health-related premonition, and she checked it out.

If the premonition is extremely vivid – if it seems “realer than real” – take it seriously.

A cardiologist I know had a vivid dream that a patient of his had a stroke while he was doing a cardiac catheterisation, which was scheduled for the next day. He wondered whether he should cancel the study, but he told himself that dreams mean nothing and pressed ahead. The next day, while actually doing the catheterisation, his patient had a stroke in precisely the same pattern he dreamed. It shook him up and completely shifted his attitude about premonitions. Now he takes them seriously.

People can become very skilled in knowing when to take a premonition seriously. They develop a refined sense over time. Practice makes perfect.

What do your colleagues in medicine think about your book?

LD: Nearly all of them are supportive. I’ve discussed premonitions with hundreds of physicians in lectures at medical schools and hospitals all over the country. I was hesitant at first, thinking they’d all probably get up and walk out. The opposite happens. They open up and share their own stories.

Following a lecture at a Harvard-sponsored conference, one female internist told me, “I see numbers in my dreams – the actual lab values of my patients’ tests – before I even order them.”

Dr. Larry Kincheloe, an OB-GYN in Oklahoma City, knows ahead of time when his patients are going to deliver because he gets strange feelings in his chest when the time is near. It’s like an alarm goes off. This is so reliable that the OB nurses caring for his patients have learned to ask him how his chest feels, as a guide to when a patient will deliver.

This is like the presentiment experiments, in which the body knows something is going to happen and starts reacting before awareness kicks in. It’s a premonition in the form of physical symptoms.

Nurses have been very supportive of my ideas. They are more open to premonitions than just about anyone. They spend more time at the bedside than doctors do. Over the years, nurses often become very precognitive. Many of them say they “just know” when a stable patient is going to have trouble, such as a cardiac arrest.

The subtitle of your book is “how knowing the future can shape our lives.” How can it?

LD: Knowing the future can help you have a future. Premonitions are often about survival. They warn us of future dangers – health problems, impending accidents, disasters, and so on.

For example, research shows that people often avoid riding on trains the day they crash, compared to normal days. On days of the crash, the vacancy rate on the train is unusually high.

This type of premonition is usually unconscious. People don’t say, “The train is going to crash. I’m cancelling my reservation.” They usually report a vague sense that something is wrong or doesn’t feel right, and they find some reason to change their plans.

People may avoid doomed planes as well. The vacancy rate on the four planes that crashed on 9-11 was 79 percent. This suggests that lots of people found some reason not to travel on those planes that day. (We don’t know for certain what this means, however, because the airlines won’t release vacancy rates for travel on the same flights for the preceding months, so there’s no way to know for sure how unusual these high vacancy rates actually were.)

But perhaps the main way premonitions affect our lives is by giving us a different way of thinking about our own consciousness, our own mind.

I discuss experiments in which consciousness can operate both into the future and into the past. This suggests that time does not limit what our consciousness can do.

This raises the possibility that our consciousness is timeless. This opens up the possibility of immortality and the survival of some aspect of our consciousness following death.

Can we learn to have premonitions? Can we cultivate them?

LD: Yes. The main thing is not to try too hard. Premonitions usually come unbidden. They largely “do” us; we don’t “do” them. So the trick is to invite them, not compel them, into your life.

First, simply realise that these experiences are extremely common, and that it’s likely that you will experience them.

Second, keep a dream journal, because premonitions occur most frequently during dreams. Record your dreams as soon as possible on waking. Most people find that premonitions become more frequent when they do this.

Third, learn to quiet your body and mind. Sit down, shut up, be quiet, and pay attention. Some people call this meditation; others simply call it “getting quiet.” Research shows that skilled meditators perform better on premonition experiments than just about anyone. Meditation opens a door to premonitions and helps us notice them when they occur.

Fourth, read about premonitions. What are they like for other people? This will help you recognise your own premonitions, and when to take them seriously.

You say that most premonitions are unconscious?

LD: Yes. Most premonitions occur in dreams. Dreams by definition are unconscious. And many experiments show that people’s bodies react to future events even before they happen, without their being aware of it.

But if premonitions are largely unconscious, how can we make use of them?

LD: Premonitions don’t have to be a detailed snapshot of the future, of which we’re fully aware, to be helpful. They can be just a hunch or a gut feeling that we act on without consciously knowing why.

Some researchers believe unconscious premonitions are the most valuable kind.

If we unconsciously know something is going to happen, we can react without processing this information by thinking about it. Thinking takes time. In dangerous situations we need to act quickly, immediately, without wasting time through reason and intellectual analysis.

As a battalion surgeon in Vietnam, I knew many soldiers who swore they had some sixth sense that kept them alive by alerting them to danger. They’d react instantly without thinking, as if “on automatic.” I suggest they were using premonitions.

I discuss an event in which an entire group of church members were late for choir practice one weekday night at a little church in Beatrice, Nebraska. The church exploded, and would almost certainly have killed them had they been there. The odd thing is that none of them had any conscious premonition that the explosion would occur, but they stayed away nonetheless. Being late was an unconscious behaviour, and it saved their life.

This sort of behaviour is very common among mothers. They often have “just a feeling” their baby is headed for trouble, and they act on this impression without knowing why. The term “mother wit,” once very common, captured this idea.

Is there a downside to premonitions?

LD: Yes. Anything can be taken to extremes. I’ve known a few individuals who won’t make major decisions without consulting a psychic. They become slaves to somebody else’s premonitions about the future.

Premonitions can be false. The mind plays tricks – sometimes dirty tricks. Hallucinations happen. Just like we can have false memories of the past, we can have false impressions of the future.

So how can we avoid being misled by premonitions?

LD: It’s pretty simple. Premonitions are a single way of knowing the future, not the only way. Whenever possible – in non-emergencies – we should rely on multiple sources of information – logic, reason, and analysis, plus intuition, hunches, and premonitions. Multiple strands of information help guard against bad decisions. When we rely on only one source of knowing, we can get into trouble. This is common sense: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Skeptics say we can’t know the future. When we appear to do so, it’s just a chance happening. What about this?

LD: The skeptics have a point. No doubt some premonitions that seem to come true are nothing more than chance happenings or lucky hits.

But to say that all the billions of people throughout human history who have experienced premonitions that turned out to be valid are deluded seems highly unlikely.

Skeptics often single out examples of premonitions that are silly or nutty, then generalise to condemn all premonitions. This is irrational. Or they say that people have selective memories. They only remember the premonitions that come true, and forget those that don’t. This is simply not true; people often recall premonitions that don’t pan out.

But even if valid premonitions are statistically unlikely, as the skeptics claim, that doesn’t necessarily mean they are false. Many things that are rare are nonetheless real. It is extremely unlikely that any particular individual can run a four-minute mile. But a few people can. It’s unfair to use statistics to dismiss rare events.

Most skeptics are poorly informed. They simply ignore the experiments showing that people can sense the future, because these studies create huge holes in their arguments. Many skeptics will not be persuaded that premonitions are real, no matter how compelling the evidence is. Personal experience is probably the best argument against the skeptics of premonitions.

I give several examples in which a skeptical spouse profoundly disagreed about whether or not his or her partner’s premonition should be taken seriously. But when the premonition came true, the skeptical spouse came around to a different way of thinking. An example is Amanda’s precognitive dream that a falling chandelier would crush their baby in its crib. The husband dismissed it as silly. But when she removed the baby from the crib and the chandelier actually fell and demolished the crib, precisely as she had dreamed, her doubting husband changed his tune.

Cases like this suggest that the best evidence for premonitions is not argument or even experimental evidence, but personal experience.

OK, so there’s evidence that premonitions are real. It’s still mind-boggling. How could these things possibly happen?

LD: I agree that premonitions seem impossible – but only if we hold onto our common-sense beliefs about how the world works.

Most people believe that our minds are confined to the present and to the brain and body. To make a place for premonitions, we have to go beyond these core beliefs. True, it seems as if we’re locked into our individual brains and bodies and the present, but the evidence from hundreds of experiments shows that this is an illusion.

Scientists don’t really know what time is. We assume it flows in one direction, which prohibits premonitions. But no experiment in the history of science has ever shown that time flows in one direction, or that it flows at all. Alternative views of time are downright cordial to premonitions.

For example, physicists talk about “closed time-like loops” that can carry information from the future into the present. This is one way premonitions might work.

Others suggest that the future is already present, already laid out, in what is called a “block universe.” During premonitions, we might gain access to this already-present information.

Other researchers suggest that the mind is nonlocal, which is a fancy word for infinite. According to this idea, consciousness is present everywhere in space and time. This means that we have access to all the information that has ever existed or will exist – past, present, and future. This opens the door for premonitions.

These are all hypotheses, of course. The main point is that our common-sense ideas about time, space, matter, and our own minds are flawed. The universe works differently than we supposed.

In view of our ignorance, we need to stay open to the evidence for premonitions and not fall back into our prejudices, as when skeptics say, “Everybody knows premonitions are impossible.”

Often in science and medicine we know that something happens before we understand how it happens. Explanations sometimes come much later. So it may be with premonitions.

If I can see the future, doesn’t that mean it is already in place and is fixed? Don’t premonitions do away with free will and freedom of choice?

LD: No. Just because you glimpse how the future is likely to unfold does not mean you can’t act to change it. When Amanda dreamed that the chandelier fell and crushed her sleeping infant, she removed the baby from the crib. The chandelier did fall, but the baby’s life was saved. She exercised her freedom of choice, and it made a life-and-death difference. There are thousands of similar examples.

Philosophers often argue against premonitions because they say premonitions destroy freedom of choice. But people who have premonitions usually don’t see it that way. Like Amanda, their personal experiences with premonitions say they do have a choice. They can act, and they do, to change the future they’ve glimpsed.

I agree with the idea that the future is probable, not fixed. According to this view, the future is fluid and subject to change. So a premonition is not inevitable.

Probability varies, of course. This means that some futures may be easier to change than others. It was easier for Amanda to act on her premonition and remove her baby from danger than for an individual to prevent an earthquake she dreamed about. Some futures may be so probable they will happen; others, perhaps most, are malleable.

What’s the Big Lesson from premonitions?

LD: Premonitions are an incredible gift. Although they are an aid to our physical survival, their main contribution is in providing us with an expanded vision of who we are and what our destiny may be. They show that we’re more than a physical brain and body. Brains can’t operate outside the present or beyond the body. But our consciousness can, as premonitions show.

Premonitions reveal that we’re not slaves to the body or to the present. We can operate outside of time; something about us is timeless. The implications are quite wonderful, because they imply immortality. Not a small contribution.

Dr. Larry Dossey’s website is www.dosseydossey.com. The Power of Premonitions: How Knowing the Future Can Shape Our Lives is available from all good bookstores.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.