Around Christmas of 1992, a man named Gary Renard, living in the remote backwoods of Maine in the northeastern corner of the US, came out of a meditation to find two stylish, good-looking people, a man and a woman apparently in their thirties, sitting on his couch. He had never seen them before and had no idea of where they had come from.

“There was nothing threatening about them,” Renard would later recall; “in fact, they looked extraordinary peaceful, which I found reassuring. Looking back on the event I would wonder why I had not been more fearful, given that these very solid-looking people had apparently manifested out of nowhere. Still, this first appearance by my soon-to-be friends was so surreal that fear somehow didn’t seem appropriate.”

The man and woman called themselves Arten and Pursah. They said they were ascended masters who had come to teach Renard some lessons about life, the universe, and Jesus Christ.

So began a strange series of episodes that would continue off and on for the next nine years and would culminate in Renard’s first book, The Disappearance of the Universe, published in 2003. The story would grow stranger. Arten and Pursah soon identified themselves as later incarnations of the two disciples of Jesus that we know as Thaddeus and Thomas respectively. They began to tell Renard about the true nature of the teaching of Jesus, whom they call ‘J.’

The portrait of ‘J’ and his times as drawn by Arten and Pursah will be more or less familiar to readers who have some familiarity with the historical Jesus as unveiled by scholarship over the past 200 years. The Gospels were not written by Jesus’ disciples or indeed by anyone who knew him personally (the one exception, Arten and Pursah say, is Mark, who met the master as a small child). The Gospels, composed some forty to eighty years after Jesus’ time, contained some authentic sayings and deeds of his as well as many admixtures and alterations to suit the developing Christian theology. “Don’t you find it a little strange that not one complete original copy of J’s own words in his own language survived the rise of Christianity?” Pursah asks.1 “Do you really think that was an accident?”

Pursah is of course right. There are traditions of early collections of Jesus’ sayings compiled in his native Aramaic, including Q (a lost source hypothetically used by Matthew and Luke), but none of these works have survived. The Gospels in the New Testament were all written in Greek. “Incredibly,” adds Pursah, “even the later Gospels were changed over the next few centuries. The ending of Mark was completely changed” – a fact that a reader can verify by looking in practically any contemporary version of the New Testament. The authentic text breaks off extremely abruptly at Mark 16:8. There are several alternate endings, none of which is believed to be authentic. The fact that Mark is regarded as the oldest and historically most reliable Gospel – and that this lost ending must have dealt with what Jesus did and said after his resurrection – makes this realisation all the more disturbing.

What, then, of the famous Gospel that is attributed to Thomas himself – the cryptic collection of sayings that first surfaced in complete form in 1945 as part of the Nag Hammadi scriptures? “You haven’t really read it, have you?” Pursah chides Renard. “Except for that time you browsed it in a bookstore – when you spent half your time looking at that beautiful woman down the aisle.” (This kind of banter characterises the dialogue between Renard and the masters, the result, they tell him, of his own sardonic sense of humour. “When you don’t need it, then we’ll no longer need it in order to get through to you,” Pursah says at one point.) According to Pursah, the Gospel of Thomas as we have it today is authentic, although it was left unfinished by Thomas himself, who was martyred in India, and it was supplemented later on. “What I will affectionately refer to from now on as Thomas is a Jewish-Christian Sayings Gospel that predated Gnosticism,” Pursah adds.

The reference to Gnosticism is significant because Thomas is generally regarded as a Gnostic Gospel, a text representing a movement of early Christians who believed that gnosis, or enlightenment, is the key to salvation. Thomas is not a Gnostic work, says Pursah. “Gnosticism was a combination of many earlier philosophies mixed in with some of the things J said or that people thought he said. Yes, you could certainly say that J had what might be described as Gnostic tendencies, but they were not all new. Some of them go back to archaic forms of Jewish mysticism.”

God “Did Not Create the World”

One of the chief points of similarity between J’s teaching as presented by Renard’s masters and that of the Gnostics is “that the world is very much like a dream and God did not create it…. God did not create duality and He did not create the world,” Pursah says. “If He did He would be the author of ‘a tale told by an idiot’, to borrow Shakespeare’s description of life.”

This is an uncomfortable idea even for the comparatively enlightened. A few days before writing this article, I was at a conference chatting with a woman who is extremely (and deservedly) well-known and admired in New Age circles. I remarked that I didn’t find this world particularly engaging and didn’t want to come back to it after this lifetime. “Come on!” she said. “What about the beauty and complexity of the universe?”

I said nothing, but Arten might have replied as he did to Renard: “As for the so-called beauty and complexity of the universe, it’s as though you painted a picture with a defective canvas and inferior paint, and then as soon as you were finished the painting started to crack and the images in it began to decay and fall apart. The human body appears to be an amazing accomplishment – until something goes wrong.”

The notion of a defective, unreal cosmos – what Pursah calls “psycho planet” – created by someone or something other than the true, good God, should be familiar to anyone who has explored Gnostic thought. But the ideas of Arten and Pursah also bear more than a faint resemblance to those in A Course in Miracles, and in fact the pair urge their pupil to obtain a copy of this work and study it seriously.

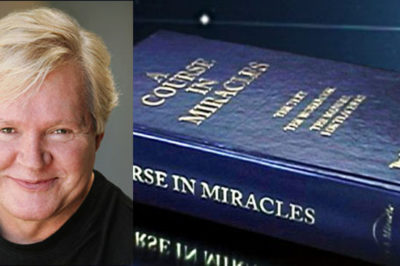

A Course in Miracles

A Course in Miracles, while familiar to many students of esotericism, remains a mysterious and elusive document. Its story is by now comparatively well-known. It was begun in 1965 when a New York psychologist named Helen Schucman heard an inner voice telling her it would dictate “a course in miracles” and that she should take notes. She complied (with some reluctance), and over the next several years took down material that would amount to some 1,200 printed pages, including a Text, a Workbook containing 365 daily lessons, and a Manual for Teachers.

With the help of her colleague, Bill Thetford, and an editor named Kenneth Wapnick, Schucman prepared the Course for publication. It first appeared in 1975, and since then has sold more than a million and a half copies. Despite this grassroots success, the Course has been given short shrift by conventional theologians. But then the circumstances of its transmission make it unlikely that the Course would be accepted in conventional circles, since the voice that dictated the material to Helen Schucman claimed to be that of Jesus Christ, correcting 2,000 years of misrepresentation of his teaching. Arten and Pursah say that the Course is genuinely the work of Jesus, and most of The Disappearance of the Universe consists of their attempt to explain the central concepts and practices of the Course.

To begin with, the Course asserts, the world is not real because it was not created by God: “There is no world! This is the central thought the course attempts to teach.” The world we see, the physical world of suffering and loss and change, is the result of a primordial separation from God – or rather, a belief that separation from God is possible. The Course says, “Into eternity, where all is one, there crept a tiny, mad idea, at which the Son of God remembered not to laugh. In his forgetting did the thought become a serious idea, and possible of both accomplishment and real effects.”

Pursah expresses the same idea in this way: “For just an instant, for just one, inconsequential fraction of a nanosecond, a very small aspect of Christ appears to have an idea that is not shared by God. It’s kind of a ‘What if’ idea…. the question, if it could be put into words was, ‘What would it be like if I were to go off and play on my own?’ Like a naïve child playing with matches who burns down the house, you would have been much happier not to find out the answer to that question,” because it would mean that our primordial innocence would be “seemingly replaced by a state of fear and the erroneous, vicious defenses that this condition appears to require.”

Here the Course diverges from classical Gnosticism. For the Gnostics, this world was fashioned by an inferior, arrogant pseudo-god whom they called the Demiurge (from the Greek word for ‘craftsman’ or ‘creator’). For the Course, the world began with a ‘tiny, mad idea’, which is the ego – the stance the fallen Son of God (which is each of us) takes in his deluded belief that he can exist apart from the Father. The apparently “real effects” include the physical world and the body itself, the “hero of the dream.”

According to the Course, the world is not fashioned by a Demiurge or a second-rate creator God (sometimes identified with the God of the Old Testament) who exists ‘out there’ in the metaphysical stratosphere. It arises out of the ego, out of what is apparently the most intimate, personal aspect of the self. Some of the Gnostic texts characterise the Demiurge in a similar way. The Apocryphon of John says of him: “And he is impious in his madness which is in him. For he said, ‘I am God and there is no other God beside me’, for he is ignorant of his strength, the place from which he had come.”

There is a curious and elusive crux here. Many investigators of Gnostic thought, including the psychologist C.G. Jung, have taken its mythology at face value: they have thought that the Gnostics believed their own myths. But it is possible that the Gnostics were not so naïve, that they were expressing truths about the human condition, but were doing so in mythological language. This would mean that the Gnostic texts are not to be taken at face value. They express certain spiritual and psychological insights that are not explicitly spelled out but which the Gnostic masters understood and explained to their pupils much as Arten and Pursah do with Gary Renard. This is a highly speculative conclusion, but we see a similar approach with contemporary Tibetan masters, who often teach by expounding highly compressed and cryptic texts to their hearers.

In this case, the Demiurge is not merely an improbable conception of God but a sharp and accurate portrait of the principle of egotism in ourselves. The ego, like the Demiurge, says “I am God, and there is no other.” Paradoxically, this very assertion shows that it is “ignorant” of its strength, “the place from which it had come” – the divine reality.2 This interpretation would bring the import of the Gnostic texts far closer to the Course.

If God did not create the meaningless world we see, if there is no ultimate reality to the ego or to its chief creation, the body, then the only appropriate response is to look past these illusions. It’s no coincidence that the Course speaks of laughing at the “tiny, mad idea” of separation.

The Course also teaches that the only sane response to any form of madness in the world is to forgive it. The Course thus takes one of the chief precepts of the Gospels – forgiveness – and elevates it to a status that it does not have and cannot have in mainstream Christianity. If, as the latter teaches, the world does have a genuine ontological reality, then the evil in it is also real. Forgiveness then becomes a kind of favour bestowed upon the unworthy – an attitude that the Course calls “forgiveness-to-destroy.” By contrast, the Course teaches the undoing of the illusory phenomenal world by literally overlooking it, by seeing past its appearances to what the Course calls the “real world” underneath. This “real world” does not exist in some millennial future; it is present now, in the “holy instant.”

This is the central idea that Arten and Pursah try to teach their pupil. Forgiveness undoes the ego by undercutting its foundation – the belief in this reality of separation and isolation. Renard’s masters stress that only what God has created is real. Since God did not create this world, it is not real. Nor, for that matter, is the body; it is utterly insignificant. The crucifixion and resurrection of Christ himself were originally intended to illustrate this very point. Consequently, everything from minor gaffes to the most apparently heinous atrocities are to be greeted with one response: forgiveness.

Entwined with forgiveness is the need for a total and complete release from fear. Fear, according to the Course, is a delusion creation by the ego. Having imagined that it is separate from God (which is impossible in reality), it incurs an enormous sense of fear for having rejected God, and we identify with this fear. As Pursah expresses it:

‘Don’t you know what you’ve done?’ – the ego asks in our metaphysical story – ‘You’ve separated yourself from God! You’ve sinned against Him big time. You’re in for it now. You’ve taken paradise – everything He gave you – and thrown it right in His face and said, “Who the hell needs you?” You’ve attacked Him! You’re dead!’

But since none of this happened in actuality, God is not angry at us and there is no reason to fear. Fortunately, the instant that the “tiny, mad idea” of separation occurred, God produced an answer: the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is, in the Course’s theology, the aspect of God that is aware both of the divine reality and of the world of suffering and separation in which we think we live. To heal our minds, individually and collectively, we must turn them over to the Holy Spirit and let him guide them completely. One of the chief ways to do this is to apply forgiveness in any and all situations, not as a gesture of condescension or noblesse oblige, but as a result of a profound recognition that none of this ever really happened. Forgiveness is justified because there is no sin and no guilt and no reason to fear. We are like a child who is suffering a nightmare of horror although it remains safely in bed under the care of a loving parent. The fact that we can begin to hear the voice of the Holy Spirit – the call to forgiveness – is a sign we are awakening.

This, at any rate, is a brief sketch of the Course as presented in The Disappearance of the Universe. It raises any number of questions, the most obvious being the nature of this strange revelation. Are we to take it at face value? Are we to believe that these beings, entities who were once disciples of Christ, materialised on someone’s couch somewhere in the Maine woods? The story becomes still harder to credit when we learn that Renard himself is both Thomas and Pursah: he was Thomas in a previous life (which he does not remember) and Pursah is his own last incarnation who will come in the future. Because time is part of the delusory fabric woven by the ego, it has no reality and can be elided or transcended.

The most evident fact about these claims is that they are impossible for us to verify. There is no way of either proving or disproving that Gary Renard experienced such visitations from alternate realities. The skeptic may deny this possibility, but he could only do so on the basis of common-sense reality, and we know (even if we did not have the Course to remind us) that common-sense reality is a great deal less substantial and consistent than we like to pretend. Renard taped the sessions with Arten and Pursah, but he destroyed the tapes after writing the book. Even if he hadn’t, all we would have would be recordings of Renard conversing with a man and a woman, which would prove nothing to doubters.

What, then, about the factual accuracy of what the masters say? Their conversations with Renard extend far beyond the Course. They claim, for example, that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus. Arten points out: “By Jewish law at that time a person’s dead body could only be anointed by their family members, and if you look in your New Testament you’ll find that even though J’s body was no longer there, Mary Mag’dalene [sic] was allowed to go to the tomb in order to anoint it. What should that tell you?” We also learn that Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, was the real author of Shakespeare’s works and that the world came close to nuclear holocaust on September 25, 1983, when Russian computers mistook the glints of light reflected off some clouds for attacking American missiles. A counterattack was launched and failed to occur only because an otherwise unknown officer named Colonel Petrov decided it was a mistake and called it off.

Curiously, the only one of these particular claims that it’s possible to verify is the last. Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov was monitoring incoming satellite data on September 26, 1983 (not September 25, as Renard’s book has it) when he received signals indicating that the Americans were launching a nuclear attack. “I had a funny feeling in my gut,” Petrov later recalled. Correctly betting that the signal was a computer error, he made a historic decision not to inform his superiors. As The Daily Mail wrote, “Had Petrov cracked and triggered a response, Soviet missiles would have rained down on US cities. In turn, that would have brought a devastating response from the Pentagon.” Instead of treating Petrov as a hero, his superiors interrogated him relentlessly and retired him on a pension that later became almost worthless.3

Other claims are far more tenuous. The Earl of Oxford has been put forward as the true author of Shakespeare’s works, but most scholars are not convinced. As for Mary Magdalene, various sources have claimed that she was Jesus’ wife, but again the evidence (despite The Da Vinci Code) is highly questionable. But if such assertions cannot be proved, they cannot exactly be refuted either.

One thing, however, can be stated more or less conclusively. The ideas in The Disappearance of the Universe, whether they were generated by Gary Renard or by his masters or by someone else, reveal a profound and highly accurate knowledge of A Course in Miracles. Indeed this book was apparently intended as a correction for the many misinterpretations of the Course that have often been put forward even by its admirers.

As a matter of fact, the Course has not been well served by its popularisers, who have tended to present it as a bland update of the American gospel of positive thinking rather than as a rigorous, difficult, but highly powerful means of spiritual development. This point, made mildly in The Disappearance of the Universe, is stressed much more sharply in its 2006 sequel, Your Immortal Reality, where Arten tells Renard, “Including yourself, you could count on two fingers the number of people who are out there on the road accurately teaching this message.” (The other is Kenneth Wapnick.) This rather harsh assessment has provoked a certain amount of hostility to Renard among a number of prominent American teachers of the Course – who are not always as pacific as one might imagine – but there is some truth in the claim.

We then face the question of whether the Course itself is authentic. Whether or not Jesus dictated it to Helen Schucman is impossible to determine. How could we evaluate the origins of an inner voice inside the head of a woman who has been dead for over twenty-five years? (Schucman died in 1981.) Nor can we make much headway by comparing the Course to conventional Christianity or for that matter the Gospels. Even the most conscientious scholars have admitted that there is an immense chasm separating Christ from Christianity and that the Gospels themselves are highly questionable as historical sources.

Despite these ambiguities, the Course remains a remarkably powerful and sophisticated (though not exactly flawless) tool for awakening the consciousness. As D. Patrick Miller, the publisher of the first edition of The Disappearance of the Universe, remarks, “The authenticity of the Course has been verified for me because it works, creating positive and dramatic change in my life and the lives of many others whom I’ve met and interviewed – but not because it purports to have a divine source.”

In cases like these, I have found it helpful to remember an esoteric maxim: Neither accept nor reject. If we can free our minds even from the dichotomy of truth and falsehood, we may be able to open them to dimensions that surpass the yesses and nos of the world we know. This may be partly what Arten and Pursah mean when they tell us the reality of the universe is nondual.

Further Reading & Study

The website for Gary Renard: www.garyrenard.com

The Course in Miracles

Forbidden Faith: The Secret History of Gnosticism by Richard Smoley

Inner Christianity: A Guide to the Esoteric Tradition by Richard Smoley

Secrets Of The Immortal: Advanced Teachings from A Course in Miracles by Gary Renard

Footnotes

- Emphasis here and in other quotations is from the original.

- For further discussion of affinities between the Course and Gnosticism, see my book Forbidden Faith: The Secret History of Gnosticism.

- See David Hoffman, “I Had a Funny Feeling in My Gut,” The Washington Post, Feb. 10, 1999, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/inatl/longterm/coldwar/shatter021099b.htm; Dec. 4, 2007. I am indebted to D. Patrick Miller for drawing my attention to this fact.

Bibliography

A Course in Miracles. Three volumes. Tiburon, Calif.: Foundation for Inner Peace, 1975.

Gary R. Renard, The Disappearance of the Universe. Berkeley, Calif.: Fearless Books, 2003.

Gary R. Renard, Your Immortal Reality: How to Break the Cycle of Birth and Death. Carlsbad, Calif.: Hay House, 2006.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.