Séances. Mediums. Apparitions. And fraud. These are a few of the things that come to mind when the subject of Spiritualism comes up. Like so many things in the world of the occult, Spiritualism presents a dual face of mystery and deception. The minute one begins to believe, one comes across evidence suggesting that the whole thing may be a hoax. The minute one starts to think it’s a hoax, evidence appears to suggest there might be something to it after all.

So also it must have seemed during Spiritualism’s heyday during the mid-nineteenth century. The craze began in the US, when in March 1848 two sisters, Margaret and Kate Fox, began to experience strange rappings in their house that, they claimed, had been generated by spirits. Soon they were able to work out a kind of Morse code with the raps so they could exchange questions and answers with the visitors from the other world.

Although the sisters’ evidence was eventually called into question – Margaret Fox later admitted the whole thing was a hoax, only to retract her confession afterward – Spiritualism became one of the great fads of the era, to the point where even Abraham Lincoln attended a séance at the White House in April 1863.

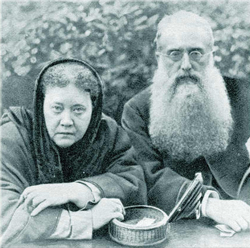

Another figure associated with Spiritualism had a rather ambiguous connection with the movement. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a Russian noblewoman turned spiritual adventurer, initially associated herself with Spiritualism, only to decry it later.

Blavatsky’s own story is surrounded by its own amount of shadows and haze. By her own account, in 1849, at the age of eighteen, she left her elderly husband (to whom she had been married for a mere three weeks) and began a worldwide search for spiritual truth that took her as far afield as England, Italy, Egypt, India, and possibly Tibet. Around 1851, she claimed, she met a master from India who agreed to give her training in occultism if she would take part in a larger mission to disseminate the teachings of universal brotherhood throughout the world.

Much of the next twenty years of Blavatsky’s life is hard to document. Both in her own account and in those of her followers, fact and legend are inextricably mixed. But one of the earliest places for which there is proof of her appearance is Cairo in 1871, where she found herself stranded after a shipwreck. Here she started a “Société Spirite [“Spiritualist Society”] “for the investigation of mediums and phenomena.” The ill-fated organisation foundered within two weeks, as the mediums drank and cheated; once a madman broke in to interrupt the proceedings. While there is evidence that the society did regroup and continue at least into the following year, Blavatsky was not part of it: she had gone further afield, first to Odessa in her native Russia, then to Paris, finally sailing to New York, where she arrived in July 1873 and where she made her first impact on a spiritually hungry public.

Indeed one of the most significant encounters of Blavatsky’s life took place through Spiritualism. In the improbable setting of a remote farmhouse in Vermont, a spirit medium named William Eddy allegedly materialised a range of ghostly beings, who appeared in period costume. Eddy would sit in a narrow closet in his farmhouse, and a blanket would be hung across the doorway. Shortly after Eddy entered the closet, the blanket would be pulled aside, and the ephemeral image of a dead person would appear, only to disappear soon afterward, sometimes in the full gaze of the spectators.

At Eddy’s farmhouse in the autumn of 1874, the visiting Blavatsky met Henry Steel Olcott, a correspondent from a New York newspaper who had come to report on the phenomenon. Olcott later recounted that on the night of Blavatsky’s arrival, the Eddys’ closet produced the shades of “a Georgian servant boy from the Caucasus; a Mussulman merchant from Tiflis; a Russian peasant girl; and others… The advent of such figures in the séance room of those poor, almost illiterate Vermont farmers, who had neither the money to buy theatrical properties, the experience to employ such if they had had them, nor the room where they could have availed of them, was to every eye-witness a convincing proof that the apparitions were genuine.”

What did Blavatsky believe about these phenomena? Her equivocal attitude toward Spiritualism is best illustrated by a clipping in her scrapbook. It is a copy of an article she wrote in 1875 entitled “The Science of Magic.” In the printed version of the article she states, “I am a Spiritualist,” but on the clipping she corrects the statement to “I am not a Spiritualist.”

These contradictions are not necessarily the result of either schizophrenia or dishonesty. Blavatsky believed that the Eddy apparitions were real occult phenomena – but they were not the spirits of the dead. According to Olcott, she told him that if the Eddy phenomena were genuine, “they must be the [etheric] double of the medium escaping from his body and clothing itself with other appearances.”

In an 1872 letter, Blavatsky explains her views: “[The Spiritualists’] spirits are no spirits but spooks – rags, the cast off second skins of their personalities that the dead shed in the astral light as serpents shed theirs on earth, leaving no connection between the reptile and his previous garment.” In the case of William Eddy, these astral shells would presumably have been using Eddy’s etheric body as a kind of subtle matter in order to manifest. In the Theosophical view, the astral body is discarded at a certain point after death. Usually it simply disintegrates as the physical body does, but under certain conditions, it can be inhabited by vortices of subtle energy that can make it appear to physical sight in the guise of the deceased.

A similar, but not identical, phenomenon was displayed by Blavatsky herself. In November 1874 Olcott visited her in New York, “where,” he reported, “she gave me some séances of table-tipping and rapping, spelling out messages of sorts, principally from an intelligence called ‘John King’.” Supposedly the shade of the celebrated buccaneer Henry Morgan, “it had a quaint handwriting, and used queer old English expressions.”

But Olcott eventually became convinced that “John King” was not the ghost of the long-dead Morgan. He later wrote, “After seeing what H.P.B. could do in the way of producing mayavic (i.e., hypnotic) illusions and in the control of elementals, I am persuaded that ‘John King’ was a humbugging elemental, worked by her like a marionette and used as a help toward my education. Understand me, the phenomena were real, but they were done by no disincarnate human spirit” (emphasis in the original).

Elementals are, in the Theosophical view, nature spirits who live on the astral and mental planes. These entities are centres of force; they do not have any form in their own right. Hence they can be shaped and controlled by human thought, responding to the preconceptions of the perceivers, individual or collective. The so-called spirit of “John King” would have been an elemental that Blavatsky shaped with the force of her own will and concentration – as perhaps she had done in the Eddy farmhouse.

The subtleties of these ideas are considerable, and it would be hard to disentangle them all in an article of this length. But the theory seems to go something like this: sometimes, as in Eddy’s case, a wandering astral shell can temporarily inhabit the etheric body of a medium and so make its presence known to the physical senses. In other instances, such as with Blavatsky’s phenomena, the will of an occultist can mould the subtle matter of the “astral light” into the shape desired.

To dismiss these ideas out of hand would, in my view, be foolish. On the other hand, to verify them would require an intense training in esoteric practices that is difficult to come by. For our purposes, though, the essential point is clear. There is a middle ground between the allegations of the skeptics – that all spiritualistic phenomena are simply fraudulent – and the beliefs of the credulous, who take everything at face value. While there have been fraudulent mediums, it would be overhasty to dismiss every spiritualistic experience as a fraud. At least some of the phenomena associated with Spiritualism seem to be the play of forces in the astral realm, that domain of thoughts and images that is as plastic as the figments of our imaginations – and indeed contains them.

SOURCES

H.P. Blavatsky, Collected Writings, vol. 1: 1874-78, Edited by Boris de Zirkoff, Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1966.

H.P. Blavatsky, The Letters of H.P. Blavatsky, vol. 1: 1861–79, John Algeo, ed, Wheaton, Ill.: Quest, 2003.

Vicente Hao Chin, Jr., Theosophical Encyclopedia, Manila: Theosophical Publishing House, 2006.

Joscelyn Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment, Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Mitch Horowitz, Occult America: The Secret History of How Mysticism Shaped Our Nation, New York: Bantam, 2009.

Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves, vol. 1, Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.