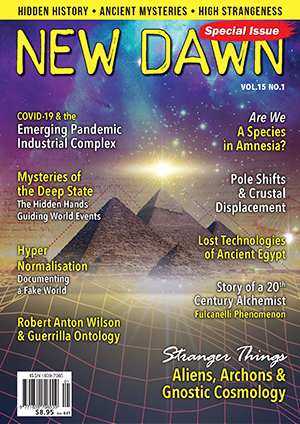

From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 15 No 1 (Jan 2021)

Although we are in the midst of an ‘information revolution’, many of us rarely question the world around us. As the political domain becomes increasingly polarised, there is a greater need for people to expose themselves to alternative viewpoints and opinions.

In theory, the internet should function as an open platform in which mainstream narratives are continually challenged, questioning the institutional authority of governments, multinational corporations and the mainstream press.

Thankfully, we can question the ‘status-quo’ thanks to numerous websites, online forums and podcasts dedicated to alternative points of view and research, including parapsychology, geopolitics and ‘conspiracy culture’. At the same time, the rise of social media has resulted in more subtle yet dangerous forms of propaganda and mind control where people are often unknowingly exposed only to those who hold similar views to their own, stuck in a ‘social validation feedback loop’.

How can we stay open-minded, questioning and pragmatic in today’s world? Guerrilla ontology may provide the answer.

What is Guerrilla Ontology?

Guerrilla ontology is a term coined by Robert Anton Wilson in his 1980 book The Illuminati Papers. Wilson defines it as an approach adopted in his novels that mixes “the elements of each book so that the reader must decide on each page, ‘How much of this is real and how much is a put on?’”1 In other words, it functions as an exercise in cognitive dissonance, where “readers are left to form their own interpretation as to which, if any, of the numerous and contradictory viewpoints presented by the characters are valid or plausible.”2 This is similar to the postmodernist claim that textual discourse can be interpreted in a number of different ways (potentially infinite) since there is no singular interpretation. Guerrilla ontology is much more than a literary technique, however. As Wilson stated in an interview:

The Western World has been brainwashed by Aristotle for the last 2,500 years. The unconscious, not quite articulate, belief of most Occidentals [Westerners] is that there is one map which adequately represents reality. By sheer good luck, every Occidental thinks he or she has the map that fits. Guerrilla ontology, to me, involves shaking up that certainty. I use what in modern physics is called the “multi-model” approach, which is the idea that there is more than one model to cover a given set of facts… It’s important to abolish the unconscious dogmatism that makes people think their way of looking at reality is the only sane way of viewing the world. My goal is to try to get people into a state of generalised agnosticism, not agnosticism about God alone, but agnosticism about everything… That’s what guerrilla ontology is – breaking down this one-model view and giving people a multi-model perspective.3

In other words, the primary aim of guerrilla ontology is to remain in a permanent state of agnosticism and interpret reality through a multitude of cultural, political, economic, philosophical, scientific and spiritual perspectives. Instead of subscribing to a single belief system, guerrilla ontology promotes a radical form of intellectual pragmatism in which contrasting ideologies are synthesised, integrated and assimilated to provide a more complex and dynamic understanding of the world.

Wilson assumes there is no ‘objective’ reality; even basic statements such as “there are 24 hours in a day” or “the world is round” are subjectively determined. This multi-modal approach results in an expansion of human consciousness in which all explanatory models are considered both ‘true’ and ‘false’ simultaneously.

To fully appreciate the implications of guerrilla ontology, it is crucial to know the meaning of the terms. Ontology is the branch of metaphysics concerned with the nature of existence or being, while guerrilla in this context refers to military tactics used by fringe groups to obtain political power – acts of sabotage, ambushes, raids and hit-and-runs. Guerrilla ontology could be considered a form of philosophical warfare in which the ontologist attempts to undermine authority by subverting the symbols, signs and semiotic systems through which power is exercised and maintained. Using specialised tactics such as culture jamming, reality-hacking, subvertising and meme-magic, the ontologist becomes an active participant in the cultural arena and generates new locations of meaning. Fomenting contradictory ideas induces a sense of confusion and disorientation, causing a malfunction in the psychological programming required for ideological control to function effectively. In this sense, guerrilla ontology is a subversive exercise, a rebellion against all ‘reality tunnels’ that govern perception and narrative.

For Wilson, internet technologies can play a fundamental role in challenging our ideological assumptions, creating a decentralised matrix of information where no singular worldview is predominant. Various public and private actors compete for cultural authority, undermining the very concept of ‘truth’ as we know it. As communication networks become increasingly globalised, there is greater exposure to different ideas, theories, concepts and perspectives. People find themselves in a position where they can no longer distinguish between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’. While there are dangers that this could lead to new forms of manipulation and control, it will also result in a new era of intellectual creativity, dynamism and fluidity. As Wilson states, this ‘information revolution’ is merely a continuum of an ongoing historical trend towards cultural relativism:

When people started trading and having commerce with one another, they had to learn things the way other people saw them. As a result, some sense of cultural relativism appeared in the ancient Greeks, who were great traders. I think that’s what’s responsible for the rise in Greek Philosophy. Unfortunately, this has always remained a minority point of view because of the entrenched power of dogmatic thought. With the rise of modern electronics, however, things have begun to change faster. We’re now living in the global village which Buckminster Fuller and Marshall McLuhan have long been predicting. I’ve actually met people in their 20s who have travelled to as many as 30 different countries in their lives. With that amount of travel and the emergence of modern electronic media, more and more people are developing a sense of cultural relativism [Wilson made these statements in 1980].4

In this sense, guerrilla ontology enables us to navigate the new ‘post-truth’ age, where user-generated content undermines the informational monopoly of mass-media gatekeepers and popularises alternative narratives, which would have previously remained on the fringes of society.

As previously noted, the purpose of guerrilla ontology is to induce a state of cognitive dissonance in which seemingly contradictory worldviews are assimilated in order to expand the boundaries of human consciousness. For Wilson, internet technologies are part of this expansion of consciousness as more and more people are exposed to different models of reality.

Cognitive Dissonance & Quantum Mechanics

While the multi-model approach described by Wilson seems at odds with the notion of ‘scientific truth’ – that we can establish certain facts about the world through empirical observation – even scientists are required to adopt a multi-model approach when describing phenomena at a quantum level.

When examining the behaviour of sub-atomic particles, the principles of Newtonian physics are no longer applicable. Instead, scientists must explain such phenomenon in terms of ‘probabilities’, the different outcomes that occur within a quantum system until the act of measurement results in the occurrence of a single outcome. For example, quantum mechanics demonstrates that light functions as both a particle and a wave, despite the fact that the former has a gravitational mass while the latter does not.5 In this sense, we are limited by the linguistic models that we have at our disposal when observing scientific phenomena.

Niels Bohr, the Danish physicist who proposed the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics, believed that mathematical equations do not describe the universe with objective precision. Rather, they describe the “mental processes that we have to put ourselves through to describe the universe.”6 For example, when we describe the universe as a three-dimensional space-time continuum, we are actually describing how our minds organise sensory experience; another life-form may experience reality as fourth or even fifth dimensional, and therefore the equations they use to describe reality will be radically different from our own. For Wilson, guerrilla ontology (or cognitive dissonance) is based on the idea that by embracing seemingly contradictory models of the world, we become aware of our own relativistic position within the universe.

Religions have known for centuries that cognitive dissonance expands the parameters of the mind. As Wilson states, “most of the occult literature of the world – aside from the 95% of it that is sheer rubbish – consists of tricks, gimmicks and games to trigger meta-programming consciousness.”7

The Upanishads, an ancient text central to Hinduism, is full of various paradoxes, intended to spiritually enlighten the reader. For example, it describes Brahman (the ultimate reality) as “non-differentiated, infinite, having neither cause, nor example, immeasurably extensive and without beginning… There is no dissolution, nor creation, neither one bound, nor the novice, neither the seeker after freedom, nor the liberated one.”8 These contradictions reveal what modern science is only beginning to discover – that reality is merely an expression of dynamic conscious thought.

Changing the Brain

In his book Prometheus Rising, Wilson provides numerous techniques to achieve a state of cognitive dissonance. For example, he asks his readers to buy a copy of Christian Science Sentinel and read all the faith healings that month, then buy a copy of The Peyote Cult by anthropologist Weston LeBarre which attributes all this to auto-suggestion, and then read Brain/Mind Bulletin and observe that similar healings are attributed to endorphins in the brain. After that, re-read all the miracles in the New Testament, using each of these filters: Jesus had the correct teaching; Jesus was employing auto-suggestion; the sufferers’ brains released endorphins when Jesus gave them positive auto-suggestion. By examining the phenomenon of faith-healing through a multitude of perspectives, one realises that no single explanation is valid, causing a paradigmatic shift in understanding.

According to Wilson, when a paradigm shift occurs – when we go from seeing things one way to seeing them another – “the whole world is remade.”9 All we can possibly ‘know’ is what our mind registers – reality is made up of nothing but thoughts. The brain, in the process of performing 100,000,000 calculations per minute, edits, organises and labels all raw “existential” experience and then classifies according to our belief systems. These systems will vary from culture to culture. What is ‘real’ to a native Inuit will not be the same as what is ‘real’ to a London taxi-driver. They occupy different ‘reality-tunnels’ since their social, economic, political and environmental perceptions of the world are radically different. Wilson describes this phenomenon as “neurological relativism” – each individual has a neurological system different from other members of the same society, enabling them to perceive reality in a unique way.

Through the practice of guerrilla ontology, one is aware that the mind and its contents are ‘functionally identical’ – the distinction between ‘me’ (mental awareness) and ‘not me’ (external reality) is merely a linguistic one. We become what Wilson calls “metaprogrammers,” individuals with the ability to continually recalibrate our “reality-tunnels.”

The metaprogramming circuit – known as the “soul” in Gnosticism, the “no-mind” in China, the “White Light of the Void” in Tibetan Buddhism, Shiva-darshana in Hinduism, the “True Intellectual Centre” in Gurdjieff – simply represents the brain becoming aware of itself.10

Wilson describes it as “the artist seeing himself in his painting, seeing himself seeing himself in his painting… It is a conscious mirror that knows it can always reflect something else by changing the angle of its reflection.”11

Modern psychology demonstrates that neural networks in the brain are able to change through reorganisation, a phenomenon described as neuroplasticity. These changes “range from individual neurons making new connections, to systematic adjustments like cortical remapping.”12 Neuroscientists used to believe that neuroplasticity only occurred during childhood, but modern research has now proven the brain can be altered during adulthood as well. Learning a new language is particularly valuable in this regard; various studies suggest that multilingualism not only restructures the brain but also boosts its capacity for plasticity. As Wilson argues, guerrilla ontology is similar to learning a language since it provides us with new ways of interpreting sensory experience. In the same way that foreign words and phrases allow us to see the world differently, so too do new belief systems expand the boundaries of human consciousness. Through meta-programming (exposing oneself to contradictory models of reality), we are able to rewire the very circuitry of our brains, resulting in more fluid and dynamic modalities of thought.

Conclusion

Guerrilla ontology is a powerful tool for breaking free from the shackles of ideology. As our world becomes increasingly complex, due to the forces of globalisation and technological acceleration, it is important that we possess the ability to transform our social, political, economic, philosophical, scientific and religious beliefs.

Those who remain in bondage to a single ‘reality-tunnel’ will inevitably get swept up in the tsunami of information and manufactured narratives. Many people will undoubtedly experience ‘existential crises’ as they encounter numerous theories, models, concepts and frameworks that challenge the stability of their foundational worldview.

To navigate what French philosopher Guy Debord called “The Society of the Spectacle,” in which authentic social life has been replaced with its representation – “All that once was directly lived has become mere representation”13 – we must learn to embrace a multi-model approach. While it is important that we remain sceptical of how internet technologies are used to manipulate our thinking, the ‘information age’ allows us to become more open-minded than ever before. As Aleister Crowley once famously stated, “Man is ignorant of the nature of his own being and powers. Even his idea of his limitations is based on experience… There is no reason to assign theoretical limits to what he may be, or what he may do.”14

Footnotes

1. guerrillaontologies.com/about/

2. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Illuminatus!_Trilogy#Cognitive_dissonance

3. J. Elliot, (1980) ‘Robert Anton Wilson: Searching for Cosmic Intelligence’, available at rawilsonfans.org/searching-for-cosmic-intelligence-interview-1980/

4. Ibid.

5. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Light

6. R. Wilson, (1983) Prometheus Rising, New Falcon Publications

7. Ibid.

8. The Yoga Upanishads (available at) archive.org/stream/TheYogaUpanishads/TheYogaUpanisadsSanskritEngish1938#page/n63/mode/2up

9. R. Wilson, Prometheus Rising

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroplasticity

13. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Society_of_the_Spectacle

14. A. Crowley, (1929) Magick in Theory and Practice, Dover Publications

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.