From New Dawn 187 (Jul-Aug 2021)

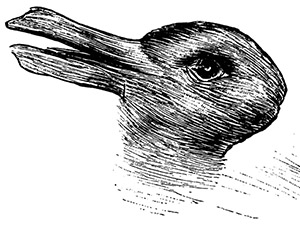

When I was in secondary school, a teacher showed me an animated optical illusion in which a dancer appears to be spinning in one direction. I was adamant that the dancer was spinning clockwise, while my teacher insisted it was spinning counterclockwise. She then told me that you could change the direction of the dancer by focusing on the feet. I gazed with meditative fixation, and suddenly, to my amazement, the dancer started spinning counterclockwise! My teacher explained that since there are no visual cues for three-dimensional depth, your mind can determine what direction the dancer spins.

At that moment, I realised that reality is a construct of the mind, and we all potentially see the same world differently. I may have put it in less eloquent terms than that (considering I was only a teenager), but there was a fundamental shift in my understanding. The illusion made me realise that the notion of ‘objective truth’ was essentially arbitrary since our subjective beliefs mediate sensory experience.

My teacher and I could have argued for hours, days or weeks as to which direction the dancer was spinning; science couldn’t have proven either of us correct since it was a matter of perception rather than ‘truth’. In ‘reality’, the dancer was spinning in both directions, but since the brain has a natural tendency to classify, categorise and catalogue information in binary terms (up/down, left/right, black/white, clockwise/counterclockwise), the animated optical illusion appears monodirectional.

There are numerous examples of this in our day-to-day lives, like when we fail to appreciate other people’s viewpoints because we perceive the world differently. We believe we are right despite the multiple (if not infinite) interpretations about the nature of reality.

What are Reality Tunnels?

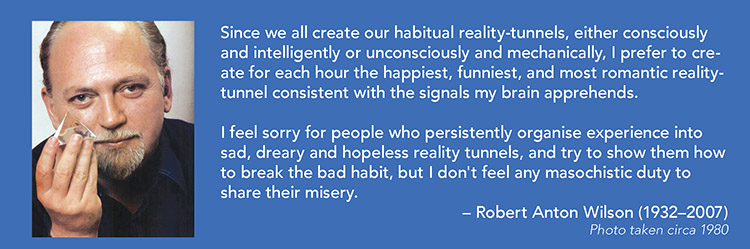

The countercultural guru Timothy Leary coined the term ‘reality-tunnel’ to describe our filtered perceptions of the world. Robert Anton Wilson later developed the concept to describe “pre-composed patterns of thinking which limit and distort the perception of reality by reducing complexity and options.”1 According to Wilson, reality-tunnels shape our phenomenological sense of self, editing out experiences that do not support our beliefs while focusing on those which do.2

An advocate for capitalism, for example, will gather facts to support the view that capitalism is the most effective socioeconomic model, discarding any information that runs contrary to this viewpoint. Similarly, a Marxist will construct arguments based on select information to support the view that communism is the best system, often neglecting evidence that contradicts their position.

As the psychedelic scholar Ido Hartogsohn states, “all of us harbour established ideas about minorities, religions, nationalities, the sexes, the right ways to think, act, feel govern, eat, drink, and what not. Reality tunnels act to help us fortify these ideas against challenging information.”3 In this sense, there is a crossover between the concept of reality-tunnels and confirmation bias, the latter described as the “human tendency to notice and assign significance to observations that confirm existing beliefs while filtering out or rationalising away observations that do not fit with prior beliefs and expectations.”4 The phenomenon of confirmation bias helps explain why people who ascribe to a reality-tunnel are oblivious. Most people believe their worldview corresponds to the “one true objective reality,” however, Wilson emphasises that many reality tunnels are artistic creations, a culmination of biological, cultural and environmental inputs.5

The notion that reality is shaped by the conditions of the human mind is not new. The 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed in his Critique of Pure Reason that experience is based “on the perception of external objects and a priori knowledge.”6 We receive information about the external world through our five senses, which is then processed by the brain, allowing us to conceptualise its contents. When I look at an object, such as a chair or a table, I have no understanding of its external nature. The qualities that enable me to denote the meaning of the object, such as shape, colour, size etc., have no objective existence; they are merely by-products of the brain.

The French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan proposed his theory distinguishing between ‘The Real’ and the ‘Symbolic’. Lacan argued that ‘The Real’ is the “imminent unified reality which is mediated through symbols that allow it to be parsed into intelligible and differentiated segments.”7 However, the ‘Symbolic’, which is primarily subconscious, is “further abstracted into the imaginary (our actual beliefs and understandings of reality). These two orders ultimately shape how we come to understand reality.”8

The Harvard sociologist, Talcott Parsons, uses the word gloss to describe how our minds come to perceive reality. According to Parsons, we are taught how to “put the world” together by others who subscribe to a consensus reality based on shared beliefs, norms and associations.9 A gloss constitutes a total system of language and/or perception. For example, the word ‘house’ is a gloss since we lump together a series of isolated phenomena – floor, ceiling, window, lights, rugs, etc. – and turn it into a totality of meaning.

The author and anthropologist Carlos Castaneda commented on this notion, stating, “we have to be taught to put the world together in this way. A child reconnoitres the world with few preconceptions until he is taught to see things in a way that corresponds to the descriptions everybody agrees on. The world is an agreement. The system of glossing seems to be somewhat like walking… we learn we are subject to the syntax of language and the mode of perception it contains.”10

The French philosopher Jacques Derrida stated that our understanding of objects (and the words which denote them) are only understood in relation to how they are contextually related to other objects (and denotive words).11

We can break free from prescribed reality-tunnels by using objects and language in unusual or disjointed ways, thereby creating new discursive meanings, associations and connotations. This was the aim and outcome of certain art movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism, as well as Brion Gysin and William Burroughs’ cut-up method.12

The famous ethnobotanist and psychonaut, Terence McKenna, argued that ideology and culture are tools “which give other people control over one’s experience and identity since they lead individuals to shape their identity according to pre-conceived forms. If a person identifies with commercial brands or with popular ideas of what is beautiful, true or important, they give away their power to other people.”13 McKenna once said that you should not see “culture and ideology as your friends,” implying that you should understand reality on your own terms rather than buying into “pre-packaged ideological and cultural ideals” such as communism, capitalism, democracy or some form of totalitarianism.14 Belief in itself, argued McKenna, was “limiting to the individual, because every time you believe in something you are automatically precluded from believing its opposite. By believing something, you are virtually shutting yourself from all contradictory information, thus once again performing the sin of imposing a rigid simplified structure upon an infinitely complex reality.”15

Much like McKenna, Wilson recommends that a “fully functioning human ought to be aware of their reality tunnel and be able to keep it flexible enough to accommodate and, to some degree, empathise with different ‘game rules’, different cultures.”16 According to Wilson, constructivist thinking, which considers how social and cultural processes determine our perception of the world, constitutes an exercise in metacognition, enabling us to become aware of how reality tunnels are never truly objective, thereby decreasing the “chance that we will confuse our map of the world with the actual world.”17

How Your Reality Tunnel Is Formed

The constraints of human biology partially limit our models of reality. As Wilson states, our DNA “evolved from standard primate DNA and still has a 98% similarity to chimpanzee (and 85% similarity to the DNA of the South American Spider Monkey). We have the same gross anatomy as other primates, the same nervous system and the same sense organs. While our highly developed pre-frontal cortex enables us to perform ‘higher’, more complex mental tasks than other primates, our perceptions remain largely within the primate norm.”18

The neural apparatus produced by our genetic coding helps create what ethologists call the umwelt, or “world-field.” Birds, reptiles and insects occupy a separate umwelt or reality-tunnel to primates (ourselves, included). For example, bees are able to perceive floral patterns in ultraviolet light, which we cannot (unless certain technologies are utilised). Canine, feline and primate reality-tunnels remain similar enough that friendship and communication can occur between these different species, however, a snake (for example) occupies such a different reality tunnel that their behaviour appears entirely alien.

As Wilson argues, the belief that human umwelt reveals “reality” or “deep-reality” is as “naïve as the notion that a yardstick shows more reality than a voltmeter or that ‘my religion is better than your religion’. Neurogenetic chauvinism has no more scientific justification than national or sexual chauvinisms.”19 He goes so far as to suggest that “no animal, including the domesticated primate, can smugly assume the world created by its senses and brain equal in all respects the ‘real world’ or the ‘only real world’.”20

Reality-tunnels are also influenced by “imprint vulnerability,” periods in our lives when early childhood/adolescent experiences “bond neurons into reflex networks which remain for life.”21 The psychological researchers, Lorenz and Tinbergen, won a Nobel Prize in 1973 for their research into imprinting, which demonstrated that “the statistically normal snow-goose imprints its mother, as distinct from any other goose, shortly after birth. This imprint creates a ‘bond’ and the gosling attaches itself to the mother in every possible way.”22 These imprints can be imposed onto literally anything. Lorenz observed a case in which a gosling, in the absence of its mother, imprinted a ping-pong ball. It followed the ping-pong ball around and, on reaching adulthood, “attempted to mount the ball sexually.”23

Wilson estimates that the age at which we are imprinted with language determines lifelong programs of “cleverness” (verbal intelligence) and “dumbness” (verbal unintelligence), since linguistic models enable us to articulate mental processing, evaluate complex ideas and communicate with those around us.24 Furthermore, how and when our first sexual experiences are imprinted can “determine lifelong programs of heterosexuality, brash promiscuity or monogamy etc.”25 In more obscure imprints, such as celibacy, foot-fetishism and sadomasochism, the “bounded brain circuitry seems quite as mechanical as the imprint which bounded the gosling to the ping-pong ball.”26

These examples suggest that experiences during childhood, when the brain exhibits optimal ‘neuroplasticity’ (a term used to refer to malleability of neural networks in the brain), can shape our reality tunnels far into adulthood. As Sigmund Freud proposed, many “rational” thoughts and behaviours are typically the result of “repressed” memories, impulses and desires, which dwell in the murky depths of the unconscious mind.27

Furthermore, reality-tunnels are shaped by social conditioning, the “sociological process of training in a society to respond in a manner generally approved by the society in general and peer groups within society.”28 Manifestations of social conditioning are multifarious but include nationalism, education, employment, entertainment, popular culture, spirituality and family life. Unlike imprinting, which usually requires only one powerful experience to set permanently into the neural networks of the brain, conditioning requires “many repetitions of the same experience and does not set permanently.”29

The processes of social conditioning vary greatly, depending on the cultural environment to which one is exposed. For example, an individual born in a Muslim country (such as Saudi Arabia) will likely believe in the teachings of the Quran and adhere to certain religious norms, customs and traditions. However, individuals born in a Western capitalist/consumerist country, or an Eastern country with Hindu or Buddhist traditions, will adhere to different cultural and behavioural codes.

Reality-tunnels are also formed through the process of learning. Much like conditioning, learning requires repetition, but it also requires motivation. Therefore, it plays “less of a role in human perception and belief than genetics and imprinting and even less than conditioning does.”30 Learning marks a major difference between how mammals, reptiles, insects and birds perceive the world. For example, snakes share the same reality tunnel since they merely act on biologically determined reflexes, with only minor imprinted differences. Mammals show “more conditioned and learned differences in their reality tunnels.”31

Humans demonstrate a higher aptitude for learning due to our highly developed cortex and frontal lobes as well as our prolonged infancy. This variability functions as “the greatest evolutionary strength of the human race” since it enables us to pass down knowledge from one generation to the next. But it also means that we can become brainwashed and label other people who do not share our beliefs as “mad,” “anti-social,” or “blasphemous.” In fact, it could be said that the majority of all wars are the result of two (or more) opposing reality tunnels fighting for supremacy. This is particularly evident in the case of religious conflict, where people kill each other in the name of “God.”

Tunnel Vision: The Politicisation of Reality

The rise of “identity politics” in the 21st century perfectly demonstrates how reality-tunnels prevent us from considering alternative perspectives and viewpoints. During the last decade, the political domain has become increasingly polarised as the left and right engage in a battle for cultural supremacy. Such polarisation was apparent in the Brexit referendum of 2016, in which 51.9% of the British public voted to leave the European Union while 48.1% voted to remain.32 The marginal success of the ‘leave’ campaign highlighted the strong division between both sides of the political spectrum. The former stressed the importance of the Union in promoting social and economic stability, while the latter emphasised the importance of national identity, sovereignty and independence.

The rhetoric employed by both the ‘leave’ and ‘remain’ campaign was so binary in its articulation that neither side engaged in meaningful dialogue; instead, the referendum became a series of baseless slogans, mottos and catchphrases – an advertising campaign designed to appeal to target demographics. The referendum was more about two separate reality-tunnels competing for ideological supremacy than a balanced analysis of benefits and risks.

The US presidential election of 2016 was a similar drama of competing reality-tunnels, shaped by masterful spin doctors and hidden persuaders who exploited modern advertising techniques to capture specific demographics based on class, age, sex, religion, geographical location and other criteria.

Donald Trump was well-known for his campaign slogan ‘Make America Great Again’ and other catchphrases that employed a lexicon of patriotism, populism and protectionism to appeal to those on the right. On the other hand, Hillary Clinton used the slogan ‘Stronger Together’ to evoke feelings of unity, compassion, and solidarity. The election became a battle between two contrasting reality-tunnels, grounded in meaningless rhetoric and hyperbole.

Another example of politicisation is the Covid-19 crisis, with the public divided into two camps – those who supported measures such as lockdowns versus the other side that rejected many of these same measures. Political polarisation demolished a sane balanced approach to the crisis, exacerbated and intensified by the ongoing political divide across the media landscape.

‘Echo Chambers’ & Identity Politics

Social media has fuelled identity politics by enabling groups and movements to generate an online presence and have real-world impacts. According to independent scholar and author Ilaria Bifarini, this results in the emergence of ‘echo chambers’ in which internet users “find information that validates their pre-existing opinions and activates confirmation bias.”33 This mechanism, says Bifarini, “strengthens one’s beliefs and radicalises them, without adding anything to information and knowledge. The result is the ideological extremism that we are observing today and in which we are taking part, where political debates have been replaced by supporters and verbal violence.”34

Another way this happens, for example, is how Google’s online video sharing and social media platform YouTube utilises algorithmic data to show users similar content to their prior engagements – content they are likely to engage with in the future, thus creating a feedback loop in which they are exposed to media reinforcing their political preferences.35 As media scholars Brooke E. Auxier and Jessica Vitak state, “many social media platforms structure their content-feeds based on what an algorithm determines to be the ‘top’ or most ‘relevant’ stories. While these tools may help users control their information and news environments – making consumption more manageable and mitigating information overload – it is possible that these tailoring tools will expose users to redundant information and singular viewpoints.”36

Both sides of the political spectrum fail to engage in meaningful discussion when they are entrapped in a single reality-tunnel, the stability of which is threatened by competing narratives. Instead, political dialogue becomes characterised by inflammatory insults, name-calling and defamation.

Loaded language – such as ‘virtue signallers’, ‘snowflakes’, ‘racist’, ‘transphobic’, ‘Islamophobic’, ‘hetero-normative’, ‘privileged’ – enables identity groups to protect the integrity of their reality-tunnel by excluding those who hold a different opinion. In the same way that religious cult leaders isolate their members from the outside world, so too do identity groups orientate themselves around a closed belief system, which is immune to criticism, contention or challenge.

In order to facilitate a more meaningful discussion, it is important that both sides learn to break free from the constraints of their reality-tunnel.

Rising Above the Fray

In his book Prometheus Rising, Robert Anton Wilson provides various techniques for challenging dominant reality tunnels. Writing in the early 1980s, Wilson suggested that “if you are a liberal, subscribe to the [conservative magazine] National Review… Each month try to enter their reality-tunnel for a few hours while reading their articles. If you are a conservative, subscribe to New York Review of Books for a year and try to get into their headspace for a few hours a month. If you are a rationalist, subscribe to Fate Magazine for a year. If you are an occultist, join the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal and read their journal, The Sceptical Inquirer, for a year.”37

To put a modern ‘spin’ on this exercise, if you follow conservative thinkers online such as Jordan Peterson or Ben Shapiro, expose yourself to leftist thinkers such as Slavoj Zizek or Noam Chomsky, and do the opposite if you are on the left. Subscribe to internet channels that do not align with your reality-tunnel. By performing this exercise, you will find that you can think about political issues in a more balanced, neutral and multidimensional way, free from the constraints of ideological dogma.

You can use the same technique with religion. In one exercise, Wilson says, “become a pious Roman Catholic. Explain in three pages why the Church is still infallible and holy despite Popes like Alexander VI (the Borgia Pope), Pious XII (ally of Hitler), etc.”38 Then explain why the Church is an immoral and outdated institution; also write three pages detailing why you believe this to be the case. If you have the time, you can perform the same exercise with other religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and even Satanism. Explain why these religions hold the key to the ‘true’ nature of ‘reality’ and then refute yourself by providing a counterargument.

You can use the same technique to become more conspiratorial in your thinking. In one exercise, Wilson says, “start collecting evidence that your phone is bugged. Everyone gets a letter occasionally that is slightly damaged. Assume that somebody is opening your mail and clumsily revealing it. Look around for evidence that your co-workers or neighbours think you’re a bit queer and are planning to have you committed to a mental hospital.”39 Observe how these assumptions influence your perception of other people and their behaviour – it won’t be long before you find evidence to support your paranoid thinking!

Once you have sufficiently experimented with this reality-tunnel, “try living a whole week with the program, ‘Everybody likes me and tries to help me achieve all of my goals’.”40 Then try living a whole month with the program, “I have chosen to be aware of this particular reality.”41 Then try living a day with the program, “I am God playing at being a human being. I created every reality I notice.”42 Then try living forever with the metaprogram, “Everything works out more perfectly than I plan it.”43 By adopting these different reality-tunnels, you will notice how malleable your perceptual faculties really are – the world can become a place of conspiracy and collusion or a place of benevolence and positivity, depending on how you view it.

Wilson provides another interesting exercise to expand the boundaries of consciousness, in which you “list at least 15 similarities between New York (or any large city) and an insect colony, such as a bee-hive or termite hill. Contemplate the information in the DNA loop, which created both of these enclaves of high coherence and organisation, in primate and insect societies.”44 Then, “Read the Upanishads and every time you see the word ‘Atman’ or ‘World Soul’, translate it as DNA blueprint. See if it makes sense to you that way.”45 According to Wilson, “Contemplating these issues usually triggers Jungian synchronicities. See how long after reading this chapter you encounter an amazing coincidence – e.g., seeing DNA on a license plate, having a copy of the Upanishads given to you unexpectedly…”46

Experimenting with different reality tunnels is a necessary practice if one wishes to challenge dominant narratives, perspectives and viewpoints and expand the boundaries of human consciousness. As we find ourselves in a post-modern ‘information age’, where an increasing number of political factions compete for informational authority, we are exposed to the hidden forces of propaganda more than ever before.

Every time we log into Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube, we allow ourselves to be manipulated by a complex system of algorithms that generates content based on our likes, dislikes, and even our differences. In order to escape the trappings of ideological dogma, we must become conscious of our biological, social and environmental conditioning and adopt a more multidimensional way of thinking.

Understanding about ‘reality-tunnels’ becomes instrumental in achieving true inner liberation since it enables us to think about the mind as a form of technological software that can be continually updated and reorganised. We achieve a state of metacognition, an awareness of one’s thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them. It is what the pioneering mind explorer John Lilly called our capacity for “metaprogramming,” the creation, revision, and reorganisation of mental programs.47

Although we are constrained by the limitations of biological programming (to a certain extent), the creativity of human consciousness is infinite, a maze of endless possibilities and potentialities waiting to be explored. As the Buddha said, “All that we are is the result of all that we have thought. It is founded on thought. It is based on thought.”48

Footnotes

1. Hartogsohn, I. (2015). The Psychedelic Society Revisited: On Reducing Valves, Reality Tunnels and the Question of Psychedelic Culture, Psychedelic Press, 3

2. ultrafeel.tv/reality-tunnel-how-beliefs-and-expectations-create-what-you-experience-in-life

3. Op cit., Hartogsohn, I. (2015), 4

4. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confirmation_bias

5. Anton Wilson, R. (1983). Prometheus Rising, Tempe, Arizona: New Falcon

6. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immanuel_Kant

7. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reality_tunnel

8. Ibid

9. Parsons, T. (1951). The Social System, Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1951

10. Sam Keen, Castaneda interview, Psychology Today, December 1972

11. Derrida, J. (1978). ‘Genesis’ and ‘Structure’ and Phenomenology, in Writing and Difference, Routledge.

12. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dada

13. Op cit., Hartogsohn, I. (2015), 1

14. Ibid, 2

15. Anton Wilson, R. (1990). Quantum Psychology: How Brain Software Programs You & Your World, New Falcon Publications

16. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reality_tunnel

17. Quantum Psychology, 74

18. Ibid, 74

19. Ibid, 75

20-24. Ibid, 76

25-26. Ibid, 76-77

27. Wollheim, R. (1971). Freud, Fontana Press

28. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_conditioning

29. Quantum Psychology, 77

30. Ibid

32. Ibid

33. Bifarini, I. Cognitive bias and echo chambers: The social media trap, www.academia.edu/40650380/Cognitive_bias_and_echo_chambers_The_social_media_trap

34. Ibid

35. Nguyen, C. Echo Chamber and Epistemic Bubbles, www.academia.edu/36634677/Echo_Chambers_and_Epistemic_Bubbles

36. Auxier, B. and Vitak (2019). Factors Motivating Customization and Echo Chamber Creation Within Digital News Environments. Social Media and Society, April-June 2019

37. Prometheus Rising, 83

38. Ibid, 159

39. Ibid, 241

40-43. Ibid, 242

44-46. Ibid, 190

47. Lilly, John C. Programming & Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer, New York: The Julian Press, Inc., 1967

48. The Dhammapada

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.