From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 12 No 5 (Oct 2018)

The word “real” in the title distinguishes the type of magic we’re discussing. This is not about the fictional magic of Harry Potter or the fake magic of Harry Houdini. This is about real magic, which falls into three main categories: divination, or perception of events distant in space or time; force of will, or mental influence of the physical world; and theurgy, or interactions with nonphysical entities.

In my book Real Magic (Harmony, 2018), I describe how these traditional, esoteric forms of magic (occultists use the term “magick”) have been scientifically studied for over a century, and why the accumulated evidence in favour of real magic is now overwhelmingly positive. This assertion might be surprising given that college textbooks teach us that magic is merely an ancient superstitious belief. But textbooks are regularly revised and updated as science marches on, and at the leading edge of science today we’re finding that some of the ancient ideas about magic are actually correct. Science and magic appear to be converging.

How do we know this?

One strong indication appeared in May 2018. The American Psychological Association (APA) is the principal organisation for academic and clinical psychologists, with nearly 120,000 members worldwide. Its flagship journal is the august American Psychologist. In the May 2018 issue, a lead article was entitled, “The Experimental Evidence for Parapsychological Phenomena: A Review.” The author was Etzel Cardeña, a psychology professor at Lund University in Sweden. After analysing ten classes of experiments exploring psychic effects (“psi” for short), the article’s conclusion was unequivocal: “The evidence for psi is comparable to that for established phenomena in psychology and other disciplines.” That this article appeared in the conservative voice of academic psychology cannot be overstated.

There are many other signs. For example, University of California statistics professor Jessica Utts was President of the American Statistical Association (ASA) in 2016. The ASA is the world’s largest organisation of academic and professional statisticians. In her Presidential Address in 2016, Utts mentioned that one area she had studied in detail for the US government was parapsychology. She said: “The data in support of precognition and possibly other related phenomena are quite strong statistically and would be widely accepted if they pertained to something more mundane.”

These are just two examples, but there is an increasing number of scientists who are willing to say to their peers, in public, that based on evaluation of the experimental evidence, psi exists. This is hardly news to the majority of the general public who already believe this, but among many scientists the mere possibility that psi might be real has been such a contentious issue that few were willing to express such positive opinions in public. The reason for the ongoing debate has had very little to do with the evidence and very much to do with the scientific worldview – that collection of ideas that form how science understands reality and our place in it.

The debate over psi has persisted for hundreds of years because generations of students have been taught that psi violates one or more unspecified laws of physics, and so any claims about it, either experiential or experimental, must be mistaken. This belief has forced psi out of the academic mainstream, and its marginal status has had important consequences. As the late Irvin Child, former chair of the psychology department at Yale University, wrote in 1985 in American Psychologist:

Books by psychologists purporting to offer critical reviews of research in parapsychology do not use the scientific standards of discourse prevalent in psychology. Experiments… on possible extrasensory perception (ESP) in dreams… have received little or no mention in some reviews to which they are clearly pertinent. In others, they have been so severely distorted as to give an entirely erroneous impression of how they were conducted.

We see these distortions starkly reflected in the contemptuous way that Wikipedia articles describe topics in parapsychology. This is a pity, not only because psi phenomena are extremely common human experiences, but because the state of the scientific evidence is so strong. Still, many journalists within the “serious” media continue to portray such experiences at best as spooky or silly, and at worst as a sign of mental illness. Despite the evidence, it’s not surprising that this topic has become an entrenched taboo.

I explored where this taboo came from, and why it persists, in Real Magic. I surveyed the history of the esoteric traditions, the classes of magical practices, magic’s relationship to psi, what scientific tests tell us about magic, and why leading-edge scientific ideas are suggesting a science/magic convergence. The bottom line was as follows: When you survey 10,000 years of esoteric history, ranging from shamanism through Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, the Kabbalah, Gnosticism, the Rosicrucians, the Free Masons, and so on, you find that they are all based on a single perennial wisdom that can be summarised in three words: Consciousness is fundamental.

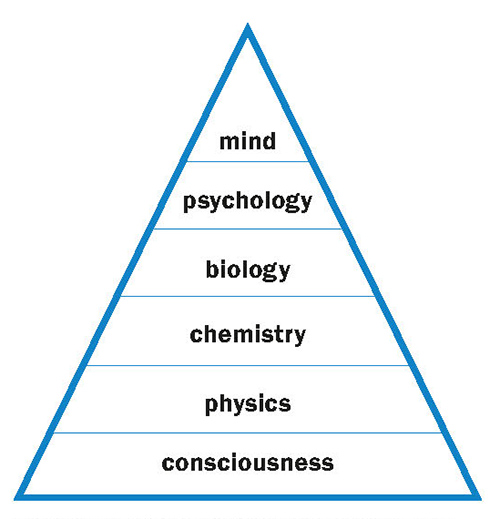

By consciousness, I mean a primordial, universal awareness, a perplexing type of “substance” that’s woven into the fabric of reality. From this esoteric worldview, scientific concepts like space, time, energy, and matter are said to emerge out of a universal consciousness. It also means that our personal sense of awareness, our self-consciousness, is composed of the same stuff. The esoteric traditions tell us that ultimately you are the universe. That is, universal awareness is the source of everything, including our bodies, brains, minds, and that spark of awareness within you that you call “me.” This is the source of the affirmation mantra “you create your own reality,” and it is meant in a literal sense. The esoteric worldview makes it far easier to understand psi experiences like telepathy and clairvoyance because the idea that awareness spans all space and time, and that it can manifest the physical world, is simply a consequence of the nature of consciousness itself.

What does this have to do with real magic?

Real magic is the pragmatic application of the esoteric worldview, just like today’s technologies are the application of the scientific worldview. That is, if consciousness is indeed as fundamental as the esoteric traditions claim, then magic must be genuine because awareness is primary over the physical world. Thus, we have the capacity to transcend the limits of space and time, and we can determine (to a small extent) how the physical world emerges. Further, human embodiment can now be seen as just one way, among a potentially infinite number of other ways, that consciousness can manifest into a physical being.

Why aren’t there university-based departments of magic? Why can’t we earn an accredited advanced degree in magical practice? The usual answer is that the esoteric worldview is so radically different from today’s scientific worldview that it cannot possibly be true. But that’s only because the scientific worldview as portrayed in the typical college textbook is five to ten years out of date. The leading edge today in science, represented by articles and books written by mainstream thought-leaders in physics, mathematics, and the neurosciences, is proposing that reality is literally made out of information. That is, the emerging scientific worldview tells us that reality is not composed of matter or energy, but rather of something far stranger, more abstract, and much closer to the esoteric worldview than the materialistic perspective that’s commonly associated with science.

Theoretical concepts aside, how can science study magic? Here’s an example involving tests of the magical force of will. These studies were sparked by asking why ancient practices of blessing food, water, and wine are still vibrantly alive in the modern world. Indeed, proposing toasts with wine and spirits are as popular today as they have been throughout history.

Anthropologists who study these practices have found that wine has been a popular beverage for at least 8,000 years. Its popularity was partially due to its pleasant psychoactive properties, but also because it was much safer to drink than water. Drinking from a pond, a river, or a well can be dangerous because the water might be contaminated. In ancient times (and still today), it was not easy to tell if water was safe or hazardous, and the alcohol in wine tended to neutralise most of those dangers.

Besides becoming a common beverage, wine was also associated with special or “holy” properties. It was celebrated by devotees of the Greek god Dionysus, and it was incorporated into the Catholic belief of transubstantiation. In these contexts, the belief was that divinely inspired intentions could alter the properties of wine, and this belief remains an act of faith for many today. But here’s the rub: Does anything actually happen to the wine that can be detected without having to rely on faith or anecdotal reports?

Research anthropologist Stephan Schwartz conducted a series of experiments to find out. In each test, he took a bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon, separated it into two carafes of equal volume, and then asked a small group of meditators to intentionally bless one of the carafes for 20 to 30 minutes. Then he randomly labelled one A, the other B, and set the two carafes aside. Later, he asked a host of a dinner party to run a taste test. The host didn’t know that one carafe contained blessed wine and the other contained unblessed or “control” wine. The host told her guests that a friend was considering buying several cases of wine and he wanted to see which one was preferred. The guests tasted each wine and marked on a card which one they preferred. The host then evaluated the group’s preference, told them the result, and thanked them for participating.

Over 12 such parties, involving a total of 93 meditators involved in blessing the wine, and 84 party guests, the results were clear. In 11 of the parties the tasters preferred the blessed wine, and in one party the preference was a tie. The odds against chance for this outcome was 2,000 to 1, indicating that under double-blind conditions the blessed wine tasted better than the non-blessed wine. This is an astounding outcome because wine-tasting is a highly complex process involving not just taste and smell, but sophisticated forms of cognitive processing, and neither the host or the party guests knew that they were tasting wine from exactly the same bottle. Something had happened to the wine as a result of the blessing.

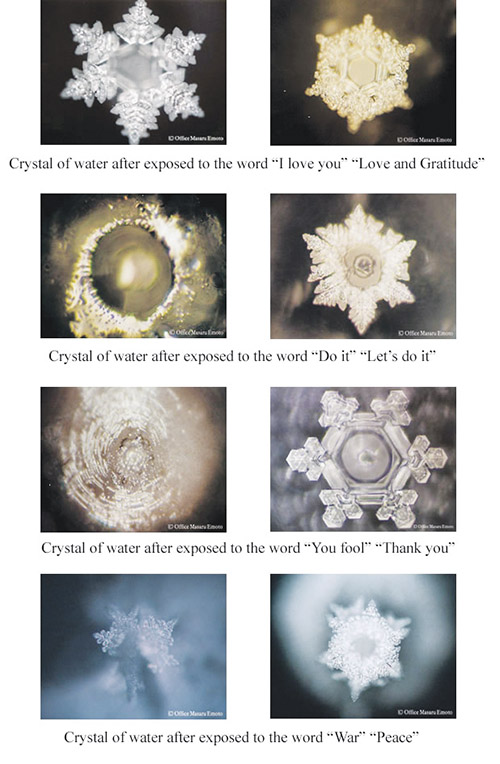

This was not the only experiment to find that focused intention altered properties of a beverage. The late Dr Masaru Emoto claimed that conscious intention could change the shape of frozen water crystals, such that pleasant thoughts would result in beautiful, symmetric crystals, while bad thoughts would result in displeasing, misshaped crystals. Emoto published many books showing results of his tests, but much of that work was more along the lines of artistic efforts rather than controlled experiments, so most scientists were not impressed by his claims.

After attending a lecture Emoto presented in 2005, we asked if he would be willing to participate in a double-blind, scientific study. He agreed, and in our collaboration the technician who took the photos of the frozen water crystals did not know if the water used to create the crystals was blessed or not blessed. The blessing in our study was performed by a group of 2,000 people who focused their intentions on bottled water from a commercial source. The unblessed, control water, was another bottle from the same source and purchased at the same time. The results showed that the blessed water produced more beautiful crystals, as assessed by independent judges. This supported Dr Emoto’s claim. Later, we conducted a more rigorously controlled triple-blind study, which again supported his claim.

We followed that up by testing if pieces of a gourmet brand of chocolate blessed by Buddhist monks and a Mongolian shaman would improve the mood of people who ate that chocolate, as compared to people who ate the same but not-blessed chocolate. Again, under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions, we found a statistically significant elevation in mood among those who ate the blessed chocolate. Later, we tried a similar experiment with people in Taiwan using oolong tea blessed by Buddhist monks. Again, people drinking the blessed tea reported statistically significant elevations in mood as compared to people drinking unblessed tea from the same source.

In these studies, we did not investigate which physical properties of wine, water, or food were altered by the blessing. But something clearly was affected.

Over the past century, many other scientific experiments have explored the effects of focused intention on physical systems ranging from elementary particles, to water, bacteria, seeds, plant growth, red blood cells, electronic circuits, and human physiology (I describe these in Real Magic).

These experiments demonstrate that modern scientific tools and techniques can be applied to ancient magical beliefs, and that when the lens of science is used to inspect magic, to our surprise we find that some of those beliefs are actually true. As science on these topics slowly advances, we may be rediscovering why these ancient practices have persisted for millennia: because they work. Explaining exactly how they work is becoming a topic of discussion at the leading edges of science today.

Despite evidence for an imminent science/magic convergence, we may not see Harvard announcing its new Department of Magical Studies any time soon. Ancient taboos about magic are still very much alive, and those prohibitions tend to reinforce all sorts of fears: Fear of the unknown, of being thought weird, of being shunned by one’s peers, and of stories about demons and black magic. Such concerns have prevented the academic world from openly and seriously acknowledging the coming convergence, even though it’s unfolding right in front of our eyes.

Fortunately, the taboo is beginning to crumble because of the popularity of books on affirmations and the law of attraction, the fast-rising mainstreaming of alternative healing therapies, development of new tools for enhancing intuition, the popularity of mindfulness meditation, the blockbuster success of superhero feature films, and in general the flourishing of “positive psychology.”

Given the many challenges faced by the modern world, I believe we would all benefit by encouraging the unprejudiced study of real magic, especially because this topic is really about gaining a better understanding of the nature of consciousness.

Indeed, a case can be made that expanding what we know about consciousness may be a prerequisite for humanity to evolve from our present adolescence phase – which like all adolescents is chronically permeated by angst and emotion – to a more mature phase where concepts like wellness for all and “peace on Earth” become genuine, realistic possibilities.

The convergence of science and magic is the theme of Dean Radin’s book Real Magic: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science, and a Guide to the Secret Power of the Universe, available from all good bookstores.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.