From New Dawn 166 (Jan-Feb 2018)

Twentieth-century Australia was a greenhouse of spirituality and occultism in their many colourful varieties, offering a revolving door to a diverse range of international teachers and practitioners who graced our shores. Among them was a mystic who drew together the threads of Hinduism, Christianity, Theosophy, Rosicrucianism and Hermeticism, assuming the nom de plume Mouni Sadhu (meaning silent monk) and spending most of the final two of his seven-odd decades in Australia.

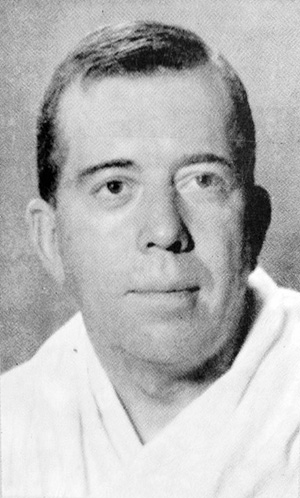

Although there are conflicting opinions about his early life, mainly because he was reluctant to disclose his background, it appears he was born as Mieczyslaw Sudowski in Poland around the turn of the last century, raised as a Catholic and served in the army in World War II before leaving his homeland.1 Thereafter he spent time in France, then Brazil, before migrating to Australia in 1948. It was here in this country that he disseminated an ideology that was to gain currency in the ensuing decades: Superconsciousness.

Mouni’s friends and followers invariably described him as a devotee of both spirituality and occultism, however he took great pains to stress that he considered these as two very distinct paths. In the foreword to his book Ways to Self-Realization: A Modern Evaluation of Occultism and Spiritual Paths he wrote, “Occultism is neither a synonymous term nor a substitute for spirituality, and spiritual men do not necessarily come from the ranks of occultists. They are two different things.”2

Having been attracted to all pathways of an esoteric nature from an early age, Mouni earned his occult label by joining local branches of the Rosicrucian Hermetic Order and the Theosophical Society in Europe during the 1920s and 30s, while at the same time studying and writing about the Tarot. He openly expressed admiration for Theosophical luminaries Madame H.P. Blavatsky, Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbeater.

A Search in India

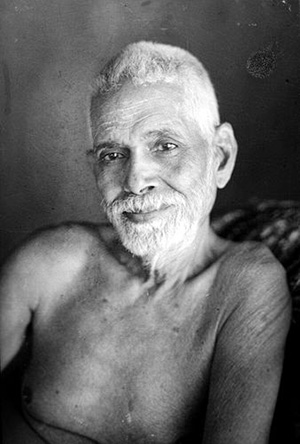

After some years, he and other members became disillusioned with these groups, leading them to break away and form their own occult lodge. A turning point came for Mouni when, during the period in France at the end of the war where he was studying the works of Paul Sédir, a friend lent him a copy of Paul Brunton’s book, A Search in Secret India. This triggered his interest in Indian spirituality and philosophy, resulting in a visit to India and his enduring reverence for the teacher he described as “the last Great Indian Rishi” – Sri Ramana Maharshi. Although Brunton’s book was first released in England in 1934, it found prominence in other Western countries during the post-war years, providing many baby-boomers with a springboard into wider esoteric explorations.

Pursuing this compelling inner urge to find his true self, or Overself as Brunton dubbed it, Mouni Sadhu sought out the Maharshi’s ashram at the foot of the sacred Arunachala Mountain in South India. Like many other devotees, he believed that just being in the presence of a genuine spiritual Master could raise one’s level of consciousness. While at the ashram Mouni claimed to have attained an enlightened state known by the Sanskrit name Nirvikalpa Samadhi, wherein duality is dissolved and the knower becomes as one with what is known.

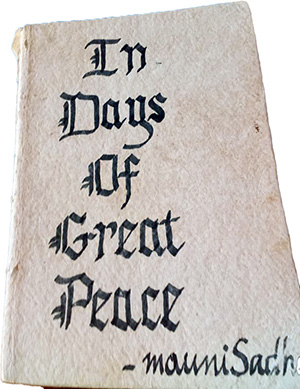

While writing a number of books about his time in India, including his ‘Mystic Trilogy’ In Days of Great Peace, he did not try to recount his Master’s teachings verbatim, preferring instead to record what he called the “real experiences of an average man” in the presence of a great sage, describing the influence it had on him personally. It was at this point that he replaced the anglicised name Michael Sadau, by which he had become known to his friends, with the spiritual title Mouni Sadhu, with Mouni meaning silent and Sadhu being translated either as wandering holy man or more simply monk. His constant theme and guiding principle was the ancient maxim, ‘Know Yourself’.

Meetings in Melbourne

On settling back in the suburbs of Melbourne after his pilgrimage to India, Mouni found work plying his skills as an electrical engineer with the Electricity Commission of Victoria. He soon linked up with other Australian devotees of Ramana Maharshi and formed an association known as the ‘Arunachala Group’, while at the same time getting involved with yoga schools around the city where he conducted classes on meditation and Eastern spirituality. Following the placement of advertisements at branches of the Theosophical Society as well as libraries and appropriate bookshops, he began delivering lectures to public assemblies of interested people, plus smaller groups of private individuals, meeting with his more permanent pupils once a month. An ad he ran in 1963 read: “The Arunachala Group is an independent group of seekers beyond all sects and religious organisations, who accept as their spiritual guide and Master, the last Great Indian Rishi – Sri Ramana Maharshi”3

At times Mouni was visited by devotees of Bhagavan’s maha samadhi from Brazil. During his time in that country in the late 1940s, Mouni wrote a booklet which was translated into Portuguese, titled Quem Sou Eu? (Who Am I?), and followers from those days kept in contact, considering him a guide and living link with their guru, Sri Ramana Maharshi. A mysterious incident occurred during one such visit to Melbourne when Mouni’s van was involved in an accident, after which he looked to be in serious condition with no sign of breathing. The Brazilians surrounded him and started chanting some Sanskrit slokas (Hindu prayers), and in due course, Mouni got up and carried on as if nothing had happened.4 Thus a certain aura and reputation grew around him.

Sydney and the Occult

Each February Mouni Sadhu would do a road-trip to Sydney in his VW campervan, and it seems, on the face of it, that he left his ‘spiritual’ label behind to revert to his more ‘occult’ side as he headed north. There he would stay at the home of his friend Nicholas Tereshchenko, who noted that Mouni met with, and gave talks to, members of the Theosophical Society, the G.I. Gurdjieff group, and students of the Tarot. He was also known to meet with the Scientologists. Tereshchenko reports that during Mouni’s 1964 Sydney visit, he helped him start a Tarot group. They developed a system whereby at each weekly meeting the person who presided over it would nominate a lecturer to speak on a chosen topic for the next meeting, and the speaker for that week would nominate the following week’s president. That way every member got to lead several meetings a year while also having to present a certain number of talks annually. “We therefore heard many different views on the Tarot, as seen by diverse people with many different occupations in life and ‘specialties’ in their interests in the occult. The meetings were held in the house of one of the librarians in the Theosophical Society,” Tereshchenko recalled.5

In this way Mouni seemed able to vent the ‘occult side’ of his personality, which he associated with the West, while he was in Sydney, in contrast to the influence of Eastern spirituality that guided his activities back home in Melbourne. One of his close associates, Bruce W. Du Vé, wrote of him: “Mouni Sadhu was to my knowledge the last practising master in the great European tradition of occultists and White Magicians. He was thoroughly versed in the history and methods of these covert arts and when I knew him lived two parallel lives. Publicly, he was a jovial, intelligent and rather mischievous though polite and formal European gentleman of the Victorian era.… The other life was a more secret one.”6 Mouni himself elsewhere asserted that he had, “reached the firm conviction that Western adepts knew as much, if not more about the value of a one-pointed mind in spiritual achievement, than their Eastern brothers.”7

On Superconsciousness

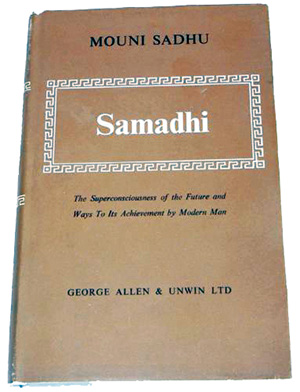

To view Mouni’s contribution to our esoteric legacy through the rose-coloured glasses of 1960s’ hippiedom, à la the faddish transcendental adventures of the Beatles, would be to devalue it. The real linchpin of his life’s work was sharing his vision for ‘Superconsciousness’ as the way forward for humanity. This is a belief that, in addition to our normal waking consciousness and our subconsciousness, we possess a third higher state of awareness that is often said to be either dormant or veiled from our everyday cognition. This central theme is highlighted by the title of his 1962 book, Samadhi – The Superconsciousness of the Future (And Ways to its Achievement by Modern Man). He taught that the most effective way to achieve such a state was through samadhi, which in India was said to exist in a number of different forms, while in some Buddhist countries such as Thailand the word is defined simply as ‘meditation’.

In his writings Mouni often referred to the philosophies not only of India but also that of Ancient Greece. It is worth noting that two and a half thousand years ago when the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, was attaining and teaching about enlightenment, the Ancient Greek philosophers were also considering the nature of the mind. The notion of a divided consciousness developed over a period of half a millennium, from the works of Homer down to Plato and Aristotle.8 And, just like some of the teachers in Athens in fourth century BCE, Mouni felt that the path to higher awareness should be open to the world at large, not confined to students of arcane mystery schools. He readily admitted that not everyone who sought knowledge had what it takes to persevere with it, and that Western minds often struggled to absorb Eastern traditions. He lamented that the dogmatic religions of the West were not producing the results intended by their founders. He was convinced the advancement of the human race would best be served by his ‘Superconsciousness-Samadhi’.

Mouni believed his vision for the future could be reached most expediently by promoting spiritual meditative practices rather than the occult, which held negative connotations for many members of the public. It should not be thought that he felt conflicted or tried to deny his occult skills; in fact, he considered supernatural and magical pursuits to be very worthwhile. They were not for everyone, however, and could be a distraction to the novice setting out on his or her journey towards Superconsciousness.

Mouni the mystic could not be accused of creating division among the arcane disciplines, considering that he drew elements of Hinduism, Buddhism and Yoga from the East together with teachings of Theosophy, Rosicrucianism and Christianity from the West. He held himself to be a Catholic right until the end of his life, and this was most likely in respect for his beloved Maharishi, who took the position that one should never convert from one religion to another, but rather convert from ‘Ignorance to Wisdom’. In his Samadhi book, Mouni summed up this devotion to the religion of his birth by describing Christ as the ‘Master of Masters’ – an expression he said was used by both Sri Ramana Maharshi and Paul Sedir.9

Marching to His Own Drum

Although Mouni Sadhu never managed to meet Paul Brunton, the two corresponded for some time by mail. Sadly, that was to end on a sour note when Mouni disagreed with the British author’s change of direction later in life, which, according to Andrew Bukraba, involved drifting towards the Buddhist practice of ‘guru bhava’.10 After Mouni’s final letter expressing his disapproval, he would not even mention Brunton’s name again. His single-mindedness in adhering to his principles caused an earlier falling out with another man he admired, G.I. Gurdjieff, who he finally got to meet during the latter’s final year of life in 1949. According to friend Nicholas Tereshchenko, the famous occultist known for the Fourth Way had insulted Mouni in his native tongue, possibly using a taunt that was common between Armenians and Poles.11 Instead of letting it slide by bowing down and paying Gurdjieff the respect he thought he deserved, the offended Polish mystic stormed out of the room, thereafter renouncing his affiliation with the Fourth Way. Nevertheless, as we have seen, the incident did not prevent him from having cordial meetings with followers of Gurdjieff in Sydney in later years.

As the eagle of the mountains, having soared high in the air above the earth,

Wings its way back to its resting place, being fatigued by its long flight,

So does the soul, having experienced the life of the phenomenal relative and mortal,

Return finally unto itself, where it can sleep beyond all desires, and beyond all dreams…

– Excerpt from the Upanishads, as quoted in Mouni Sadhu’s Concentration

In the forty-five years since Mouni Sadhu (17 August 1897 – 24 December 1971) passed away, there has been no major organisation formed in his wake, although he remained in the hearts of his followers and friends. These days the term ‘Superconsciousness’ might well conjure up the speculations of modern quantum physics rather than Eastern mysticism. Such an association would probably not displease Mouni – after all, his stated aim was to see it carry us “beyond religion.” If anything ever unites science and religion, quantum physics would be the ideal candidate, with its claims that the observer affects the thing being observed, a close match to the ideal of samadhi, wherein duality is dissolved and the knower becomes as one with what is known.

In one final practical legacy, Mouni’s literary estate was left to the Australian Society of Authors, of which he was a member. The royalties that have accrued from the estate now provide services to Australian authors.12

New editions of Mouni Sadhu titles are available here: spirit.aeonbooks.co.uk/author/mouni-sadhu/23722

Footnotes

1. The most reliable data comes from www.mounisadhu.com although other commentators such as Andrew Bukraba, Nicholas Tereshchenko and Bruce W. Du Vé all state on their websites that he was Russian.

2. The source for this quote is en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouni_Sadhu

3. www.mounisadhu.com/tereshchenko-on-sadhu.html

4. From the notes of Andrew Bukraba, www.mounisadhu.com/bukraba-on-sadhu.html

5. www.mounisadhu.com/tereshchenko-on-sadhu.html

6. From Bruce W. Du Vé’s site: www.mounisadhu.com/duve-on-sadhu.html

7. Source for this quote is en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouni_Sadhu

8. For more on the Ancient Greek view of consciousness see en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Consciousness_Studies/Early_Ideas

9. en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouni_Sadhu

10. www.mounisadhu.com/bukraba-on-sadhu.html

11. www.mounisadhu.com/tereshchenko-on-sadhu.html

12. en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mouni_Sadhu

References

Quem Sou Eu? (Who am I?), 1948

In Days of Great Peace – at the Feet of Sri Ramana Maharshi – Diary Leaves from India, first published in 1952, printed by Ramnarayan Press, Bangalore, India

In Days of Great Peace – the Highest Yoga as Lived, 2nd ed. revised and enlarged, 1957, George Allen and Unwin

Concentration – A Guide to Mental Mastery, 1959 (USA) edition published by Harper and Brothers, New York. Published in Great Britain as Concentration – An Outline for Practical Study, 1959, George Allen and Unwin

Ways to Self-Realization – A Modern Evaluation of Occultism and Spiritual Paths, 1962, in the USA by The Julian Press, and in 1963 in Great Britain by George Allen and Unwin

Samadhi – The Superconsciousness of the Future, 1962

The Tarot – A Contemporary Course on the Quintessence of Hermetic Occultism, 1962

Theurgy – The Art of Effective Worship, 1965

Meditation – An Outline for Practical Study, 1967

Initiations by Paul Sédir; translated from the French by Mouni Sadhu, 1967

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.