From New Dawn 189 (Nov-Dec 2021)

The Millennium was a time of spiritual reflection for many people. Objectively, it was an arbitrary date on the calendar, but psychologically people invested the occasion with hope and caution about the future.

Media cited pseudo-science about Y2K, the fictional Millennium Bug painted as real that would shut down everything run by computers as soon as the digits exceeded 99 and reset to zero. Evangelicals preached doomsday, pointing to the Apocalypse foretold in the Book of Revelation. The prophecies of Nostradamus (Michel de Nostredame, 1503-66) were interpreted as such that the world would end.

In the mid-1990s, the creators of The X Files introduced Millennium, a dark detective show about an investigator connected to a secret society, whose symbol was the ouroboros: the serpent eating its own tail, signifying eternal destruction and rebirth. In “Destination Eschaton,” a pop band, The Shamen, sang to a disposable beat that “Up out of the turbulence/A better order shall emerge.” A series of movies, including Ed TV (1999) and The Truman Show (1999), gave unthinking audiences their first taste of Gnosticism: that perhaps their “reality” is not real at all. Perhaps forces outside their immediate perception orchestrate their fate: secret societies, intelligence agencies, aliens, demons, or even gods.

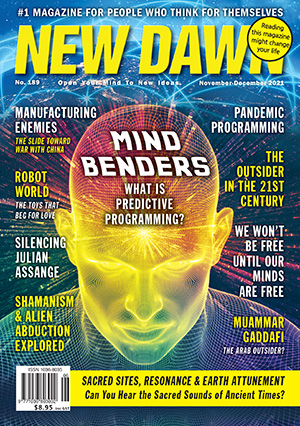

WHAT IS PREDICTIVE PROGRAMMING?

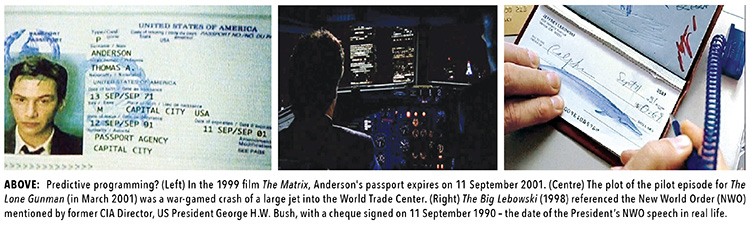

By far the most financially successful movie in the “waking up” triptych was The Matrix (1999), written and directed by the Wachowski brothers (now sisters). In the film, the protagonist Thomas Anderson learns that “reality” is a computer simulation and that humans are actually kept in vats so that machines can feed off their energy. Born on either 11 March 1962 or 13 September 1971, depending on which of Anderson’s records are viewed by the agents, his passport was first acquired on 12 September 1991 and expires on 11 September 2001. The odds of that date being a coincidence in the context of the millenarianism surrounding the film are astronomical. Passports typically need renewing every decade, so even sticking to the year 2001, the odds are 364 to 1 that that date was randomly selected. But why 1991 for Anderson’s first passport? Why not two, three, four years prior or later?

Similarly, in the Coen Brothers’ classic The Big Lebowski (1998), the film consciously references the New World Order (NWO) first proposed by former CIA Director, President George H.W. Bush. In the movie, the protagonist watches Bush on a store TV talking about Iraq’s aggression against Kuwait, the context in which he mentioned a NWO in real life. The soundtrack is Bob Nolan’s “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” performed by Sons of Pioneers. Foreshadowing the collapse of the Twin Towers, it begins: “See them tumbling down/Pledging their love to the ground.” The second verse is cut so the third is prioritised in the movie: “I know when night has gone/That a new world’s born at dawn.” The date on the cheque the protagonist gives to the clerk is 11 September 1990: the date of the President’s NWO speech in real life.

Shortly before the actual 9/11, an X Files spinoff called The Lone Gunman piloted (no pun intended) with an episode in which elements with the federal government turn a war-gamed crash of a large jet into the World Trade Center (“Scenario 12-D”) into the real thing to blame a Middle East country and boost the arms market. The only red herring in the script is that the real 9/11 was motivated by world domination, not just boosting arms sales.

The conspiracy researcher Alan Watt, who died recently, popularised the above as “predictive programming.” In his theory, the elite (whom he believed to be members of ancient cults) socially engineer society by introducing shocking new concepts into the public psyche through entertainment, i.e., when the critical guard is down, so that social responses to the impending shock are lessened and do not result in revolutionary rejection.

Others have taken Watt’s ideas further and suggested that occult groups operating at high levels of the entertainment industry and intelligence services reveal their plans to the uninitiated in order to attain spiritual “permission” and consent for their crimes. The theory goes that if the masses are too stupid to realise what is coming, that is their fault. They have been warned through entertainment.

The later trajectory of the predictive programming theory has descended into lunacy and outright lying. For instance, proponents of the theory (perhaps “trolling” as people say these days) re-edited an episode of Family Guy (a Simpsons rip-off) to make it seem as if the show had predicted the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013.

What can be proven, however, and is the subject of this article, is that when the state starts the slow drumbeats of war, including new cold wars, elements of the entertainment industry – which are inexorably tied to the military – produce films and TV shows that demonise the future enemy and prime domestic audiences for conflict with the new “other”: Latin American revolutionaries in ‘80s action movies, Islamic terrorists in ‘90s blockbusters, evil Russian gangsters in millennium-era thrillers, and increasingly Asians, as China becomes the new theatre of battle.

PROJECTING POWER: HOLLYWOOD’S WAR MACHINE

Corporate news media have by far the greatest influence in shaping public perceptions of foreign governments and peoples. Every day, millions of people are bombarded with negative messaging about “others” in countries that are strategically significant to the US Department of Defense (DoD, a.k.a. Pentagon). But the general cultural hegemony of mass media propaganda is boosted by popular television shows and cinema.

US military assistance to film producers dates back to at least 1915 when the Home Guard loaned equipment to D.W. Griffith for his racist silent movie, The Birth of a Nation (1915). The Hollywood-Pentagon alliance was cemented during the Second World War and Cold War. Communications expert Professor Tricia Jenkins noted more than a decade ago: “The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Secret Service, the National Institute of Health and the Department of Homeland Security are just a few bureaus that hire entertainment industry liaisons, and some have worked with Hollywood for over 50 years.”

In 1942, with the US entering the War, the Pentagon opened the Motion Picture Liaison Office. Hollywood producer Walter Wanger summarised the power of propaganda by describing his industry’s 120,000 movies as “American ambassadors.” As early as the 1920s, the US State Department’s Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce Motion Picture Section was using American embassies to facilitate Hollywood movies, but the practice really took off during the War. US President Roosevelt’s Office of Wartime Information, founded in 1942, acted as a censor. A 1944 State Department memo, “American Motion Pictures in the Post-War World,” offered assistance to Hollywood studios for shaping the pro-American world order, assuming that the Nazis would be defeated.

In 1943, a memo by the Office of Strategic Services (the CIA forerunner) described cinema as “one of the most powerful propaganda weapons at the disposal of the United States.” OSS agents funded director John Ford’s company Argosy Pictures. In addition, Frank Wisner of the Office of Policy Coordination recruited the MGM agent producer Carlton Alsop. Part of his job included countering the Soviet narrative of racist America by placing into films “well dressed Negroes as a part of the American scene, without appearing too conspicuous or deliberate.” The western, Charles Marquis’s Arrowhead (1953), originally had realistic scenes of US officials abusing indigenous Americans. To make America look good, Alsop rewrote the script and even redubbed scenes. Alsop part acquired the rights to Animal Farm so that when the animated movie was made, critiques of capitalism could be minimised by the CIA’s Psychological Strategy Board.

A December 1955 Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) meeting sought to use Hollywood as a way of informing the public about “the true conditions existing under Communism in simple terms and to explain the principles upon which the Free World way of life is based.” The culture war would “awaken free peoples to an understanding of the magnitude of the danger confronting the Free World; and to generate a motivation to combat this threat.” A year later, the JCS held meetings with director John Ford, producer Colonel Merian C. Cooper, actors Ward Bond and John Wayne.

The OSS/CIA operative and US Air Force Officer Edward Lansdale developed a personal friendship with the South Vietnam puppet President, Ngô Đình Diệm. Graham Greene’s novel, The Quiet American, was rumoured to be based on the life of Lansdale. When director Joseph Mankiewicz wanted to adapt the novel, Lansdale suggested script rewrites omitting OSS/CIA involvement in aspects of the story. Robert Lantz, Vice President of the film production company Figaro Inc., met with CIA director Allen Dulles to secure the assistance of the South Vietnamese government in the production.

Was this predictive programming? Not in the strict sense of The Matrix etc., noted above, but radio host and academic Pearse Redmond says: “In a broader sense, the film achieved success in preparing the American public for what soon became one of their longest and bloodiest wars.”

In 1965, John Wayne wrote to US President Lyndon B. Johnson about his intention to make a Vietnam movie, Ray Kellogg’s The Green Berets (1968). “[It is] extremely important that not only the people of the United States but those all over the world should know why it is necessary for us to be there” in Vietnam, wrote Wayne. “The most effective way to accomplish this is through the motion picture medium.” Johnson’s adviser, Jack Valenti, later President of the Motion Picture Association of America, persuaded the President: “If [Wayne] made the picture he would say the things we want said.” The buried lead here is that the President green-lighted a film, rather like in the Soviet Union where art was approved or rejected by committee. The spate of Vietnam movies began as late as 1975 at War’s end, making Wayne a pioneer of propaganda.

HOLLYWOOD’S WAR ON TERROR

Valenti later said: “[I]f things get tough [for the pro-war US image], the Democrats and Republicans know precisely what to do: Call Steven Spielberg or Arnold Schwarzenegger.” The first Hollywood movie depicting Arabs as terrorists was Sirocco (1951). The theme continues to the present and has been documented by Jack Shaheen in his book, Reel Bad Arabs (2003).

“Circa 1995,” the CIA created a new position: the Entertainment Industry Liaison (EIL), first headed by ex-covert operations officer Chase Brandon whose work is credited in Tony Scott’s Enemy of the State (1998), Tim Matheson’s In the Company of Spies (1999), Roger Donaldson’s The Recruit (2003), and Phil Alden Robinson’s Sum of All Fears (2003). Brandon’s cousin is actor Tommy Lee Jones. The EIL follows the CIA’s Strategic Intent doctrine: to project its professed values and drive recruitment. Jenkins interviewed Brandon’s successor, Paul Barry (also ex-special ops), who explained that the Agency had a public image problem that Hollywood could fix. Barry says: “In most instances, Hollywood is the only way the public learns about the Agency and Americans frequently shape their judgments about us based on films.” He added: “The problem is compounded when we are depicted as killers and rogues in the movies.”

Established in 1999, California University’s Institute for Creative Technology was funded by the US Army. After 9/11, a three-day summit was held in which 30 anonymous directors, screenwriters, and producers “brainstormed” ideas. Leaked names included Danny Bilson, David Engelbach, David Fincher, Spike Jonze, Randal Kleiser, Mary Lambert, Paul De Meo, and Steven E. de Souza. Supposedly, the Pentagon wanted to cull the ideas of storytellers to see if any scenarios might happen in real life. In October 2001, the State Department’s Office of Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs was given $15 million to create entertainment that counters the “poor perception” of the US in the third world.

Today, the DoD has a Film Liaison Office. Its former head, Colonel Phil Strub (ret.), describes the relationship with Hollywood as one of “mutual exploitation.” Typically, a producer seeking access to military hardware or personnel to include in a movie will approach the DoD Project Office and sign a Production Assistance Agreement to lease tanks, aircraft, or even soldiers. Films that have been turned down for portraying the DoD in a bad light include Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1987, too antiwar), Rob Rainer’s A Few Good Men (1992, internal killing and cover-up), Robert Zemeckis’s Forrest Gump (1994, implies that only idiots join the military), Terrence Malick’s Thin Red Line (1998, too antiwar), David O. Russell’s Three Kings (1999, negative portrayal of soldiers), and Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008, makes bomb disposal units seem unprofessional).

Following exposure that the Pentagon was “controlling” Hollywood, the Liaison Office developed a 10 percent doctrine: if just 10 percent of the script is questionable from the military’s viewpoint, the Defense Department will assist the filmmakers. After 9/11, the Defense Department’s PR manager Victoria Clarke pioneered embedding producers with soldiers for the show Profiles from the Frontline. The technique was later adopted, infamously, by journalists; a practice that led to many doubting the independence of war correspondents.

Professor Tom Pollard noted the Obama administration’s planned “pivot” to Asia and examined the Hollywood stereotypes of peoples from the region as a form of predictive programming. WWII and post-WWII Asian stereotypes included the yellow peril (criminals), perpetual foreigners (unassimilated), geishas (sex objects), and model citizens (polite nerds). Pollard gives no indication that he believes in a predictive programming conspiracy, but in the context of anti-Japan propaganda, notes that Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor (2001) “arrived in theatres just weeks before the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Although produced before the 9/11 attacks,” says Pollard, “Bay’s film epitomises post-9/11 movie making and anticipates the Asian/Pacific pivot in US foreign policies.” In 2012, MGM changed the villains in Dan Bradley’s Red Dawn (2012) from Chinese to North Koreans as not to alienate the potentially lucrative Chinese market. Anti-China hawks saw this as a conspiracy: that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had taken over Hollywood.

THE NEW YELLOW PERIL

The state typically targets intellectuals who shape doctrines and inform the culture. The US consulate in Shanghai screened several US films to university students. Embassy officials also met with Nanjing University students to discuss Lu Chuan’s Nanjing! Nanjing! (2009), the movie about Japanese atrocities committed in the eponymous province. In addition, the US Embassy in Beijing’s Center for Educational Exchange ran a Q&A session with Li Yang, director of Mang Shan (2007), a film controversial in China because it exposes human trafficking in the country and highlights the weakness of the CCP.

The Yellow Peril is a racist anti-Asian slur that had its origin in late-19th century European imperialism that sought to portray those in the rival region of the world as a danger to white Christians. Novelist Arthur Henry Ward (Sax Rohmer, 1883-1959) first published his Fu-Manchu series in 1912. The eponymous character is a criminal who seeks to assassinate British diplomats in Burma. The stories and books were pro-British imperial propaganda that portrayed Asians as threats to English “values.” In the 1970s, writer Steve Englehart and artist Jim Starlin adapted the character Fu Manchu into a Marvel comic book character, Shang-Chi, the Master of Kung Fu. Marvel was seeking to profit from the Bruce Lee movies trend in the ‘70s. “The Shang-Chi series harked back to Yellow Peril comics of the Cold War 1950s,” says cultural historian Christopher Frayling.

Produced by Marvel Studios, distributed by Disney, and directed by the American Destin Daniel Cretton, the new movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings revives Yellow Peril propaganda, only this time avoiding accusations of blatant racism by making both the protagonists and antagonists Asian, as well as having a director of Japanese-European heritage. Although the name has been changed, Fu Manchu is a character in the movie. Film critic Shi Wenxue says: “Chinese audiences cannot accept a prejudiced character from 100 years ago is still appearing in a new Marvel film.” In addition, the protagonist is played by Simu Liu, a Chinese-born Canadian who has been vocally critical of the CCP. The political context in which this anti-CCP film is released is America’s ongoing military “pivot” to Asia.

Setting the Stage from the Top Down

Quoting anti-China right-wingers in the US, the BBC publicised a report by PEN International, claiming that China has increasing control over Hollywood. The report appeared in the context of the global pandemic, to which those seeking to blame China refer to as the “CCP virus.”

Prior to the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, US television in particular produced a number of shows priming audiences for a pandemic. Many conspiracy researchers believe these to be examples of “predictive programming.” In recent times, they point to the Netflix documentary, Pandemic: How to Prevent an Outbreak, released in January 2020 just before Covid was internationally recognised.

Whether predictive programming is real or not, and regardless of the extent to which it is real, we can be certain that those who dominate the culture do so as part of a nexus of control that includes economics and foreign policy.

Footnotes

1. For instance: Michael S. Hyatt (1998) The Millennium Bug: How to Survive the Coming Chaos, Regnery.

2. Darrell L. Bock, Stanley N. Gundry and Kenneth L. Gentry (1999) Three Views on the Millennium and Beyond, Zondervan Academic.

3. John Hogue (1987) Nostradamus and the Millennium, Doubleday.

4. Sean Martin (2006) The Gnostics: The First Christian Heretics, Pocket Essentials.

5. Hans Jonas (2015) The Gnostic Religion: The Message of the Alien God and the Beginnings of Christianity, Beacon Press.

6. The Hollywood Reporter, “Boston Marathon Bombing: Seth MacFarlane Calls ‘Family Guy’ Hoax ‘Abhorrent’,” 16 April 2013, www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-news/boston-bombing-seth-macfarlane-calls-440456

7. Matthew Alford and Tom Secker (2017) National Security Cinema: The Shocking New Evidence of Government Control in Hollywood, Drum Roll Books.

8. Quoted in Tricia Jenkins (2009) “How the Central Intelligence Agency works with Hollywood: An interview with Paul Barry, the CIA’s new Entertainment Industry Liaison,” Media, Culture and Society, 31(3): 489–95.

9. Quoted in Paul Moody (2017) “Embassy cinema: what WikiLeaks reveals about US state support for Hollywood,” Media, Culture and Society, 39(7): 1063-77.

10. Moody, op. cit.

11. Pearse Redmond (2017) “The Historical Roots of CIA-Hollywood Propaganda,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 76(2): 280-331.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Quoted in Lawrence Suid, “Hollywood and Vietnam,” Film Comment, 15(5): 20-25.

15. Quoted in Ali Serdouk (2021) “Hollywood, American Politics, and Terrorism: When Art Turns into a Political Tool,” Arab Studies Quarterly, 43(1): 26-37.

16. Jenkins, op. cit.

17. Michael C. Frank (2015) “At War with the Unknown: Hollywood, Homeland Security, and the Cultural Imaginary of Terrorism after 9/11,” Amerikastudien, 60(4): 485-504.

18. Sebastian Kaempf (2019) “‘A relationship of mutual exploitation’: the evolving ties between the Pentagon, Hollywood, and the commercial gaming sector,” Social Identities, 25(4): 542-58.

19. Quoted in Lawrence Suid, “Hollywood and Vietnam,” Film Comment, 15(5): 20-25.

20. Kaempf, op. cit.

21. Tom Pollard (2017) “Hollywood’s Asian-Pacific Pivot: Stereotypes, Xenophobia, and Racism,” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 16: 131-44.

22. Moody, op. cit.

23. Jenny Clegg (1994) Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril: The Making of a Racist Myth, Trentham.

24. Christopher Frayling (2014) The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu and The Rise of Chinaphobia, Thames and Hudson.

25. Quoted in Rhea Mogul, “Marvel’s ‘Shang-Chi’ was made with China in mind. Here’s why Beijing doesn’t like it,” NBC, 3 October 2021, www.nbcnews.com/news/china/marvel-s-shang-chi-was-made-china-mind-here-s-n1280571

26. BBC, “Hollywood censors films to appease China, report suggests,” 6 August 2020, www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-53676789

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.