From New Dawn 98 (Sept-Oct 2006)

Cancer is the most frightening human disease and its cause remains elusive. Therefore, it seems inconceivable that the discovery of a germ cause of cancer would provoke such hostility among the cancer establishment. But, in truth, the belief in a cancer germ has always been the ultimate scientific heresy.

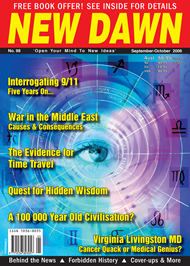

In the long history of cancer research there was never a physician more outspoken and controversial than Virginia Wuerthele-Caspe Livingston (1906-1990). For more than 40 years she championed the revolutionary idea that bacteria caused cancer and devised a treatment to try and combat these microbes by immunotherapy.

Sixteen years after her death she is now largely forgotten but still condemned by such powerful organisations as the American Cancer Society and blacklisted on Quackwatch, a self-proclaimed “non-profit corporation dedicated to combating health-related frauds, myths, fads, and fallacies.”

Livingston’s Cancer Research

Beginning in the late 1940s, Livingston was able to grow bacteria from cancer tumours; and when she and her associates injected cancer bacteria into laboratory animals, some developed cancer. Other animals developed degenerative and proliferative diseases, and some animals remained healthy. Livingston believed the “immunity” of the host was an important factor in determining whether cancer would develop.

In 1969 at a meeting at the New York Academy of Sciences, Livingston and her colleagues proposed that cancer was caused by a highly unusual bacterium which she named Progenitor cryptocides – Greek for ‘ancestral hidden killer.’ Nevertheless, Livingston claimed elements of the microbe were present in every human cell. Due to its biochemical properties, she believed the organism was responsible for initiating life and for the healing of tissue – and for killing us with cancer and other infirmities. Critics of this research continued to insist there was no such thing as a cancer germ.

In her attempt to use a variety of modalities (diet, supplements, antibiotics, as well as traditional methods) to treat cancer, she utilised an ‘autogenous’ vaccine derived from the patient’s own cancer bacteria found in the urine and blood. Livingston explained it was not an anti-cancer vaccine, but rather a vaccine to help stimulate and improve the patient’s own immune system. The administration of this unapproved vaccine caused a furore in the cancer establishment and eventually legal action was undertaken against her and the Livingston-Wheeler Clinic in San Diego. In spite of all her legal troubles, she continued seeing patients until her death at 83.

In March 1990, the year of her death, a highly critical article on the Livingston-Wheeler therapy appeared in the American Cancer Society-sponsored CA: A Cancer Journal for Physicians. (No authors were listed.) The report advised patients to stay away from the San Diego clinic and claimed:

“Livingston-Wheeler’s cancer treatment is based on the belief that cancer is caused by a bacterium she has named Progenitor cryptocides. Careful research using modern techniques, however, has shown that there is no such organism and that Livingston-Wheeler has apparently mistaken several different types of bacteria, both rare and common, for a unique microbe. In spite of diligent research to isolate a cancer-causing microorganism, none has been found. Similarly, Livingston-Wheeler’s autologous vaccine cannot be considered an effective treatment for cancer. While many oncologists have expressed the hope that someday a vaccine will be developed against cancer, the cause(s) of cancer must be determined before research can be directed toward developing a vaccine. The rationale for other facets of the Livingston-Wheeler cancer therapy is similarly faulty. No evidence supports her contention that cancer results from a defective immune system, that a whole-foods diet restores immune system deficiencies, that abscisic acid slows tumour growth, or that cancer is transmitted to humans by chickens.” (The full report is on-line at caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/reprint/40/2/103)

Bacteria As A Cause Of Cancer

The recognition of disease-producing bacteria allowed medical science to emerge from the dark ages into the era of modern medicine. In the late nineteenth century when diseases like tuberculosis (TB), syphilis, and leprosy were proven to be caused by bacteria, some doctors also suspected human cancer might have a similar cause.

The idea that bacteria cause cancer is considered preposterous by most physicians. However, despite the antagonistic view of the American Cancer Society and medical science, there is ample evidence in the published peer-reviewed literature that strongly suggests that ‘cancer microbes’ cause cancer.

According to reports by Livingston and various other researchers, cancer is caused by pleomorphic, cell wall deficient bacteria. The various forms of the organism range in size from submicroscopic virus-like forms, up to the size of bacteria, yeasts, and fungi. In culture and in tissue the bacterial forms are variably ‘acid-fast’ (having a staining quality like TB bacteria). These bacteria are ubiquitous and exist in the blood and tissues of all human beings (yet another ‘heresy’). In the absence of a protective immune response, these cell wall deficient bacteria may become pathogenic and foster the development of cancer, autoimmune disease, AIDS, and certain other chronic diseases of unknown etiology.

Needless to say, all this research fell on dead ears because bacteria were totally ruled out as the cause of all cancers in the early years of the twentieth century. Thus, bacteria observed in cancer were simply dismissed as elements of cellular degeneration, or as invaders of tissue weakened by cancer, or as ‘contaminants’ of laboratory origin.

Livingston And Progenitor Cryptocides

Beginning in 1950, in a series of papers and books, Livingston and her co-workers claimed the cancer microbe was a great imitator whose various pleomorphic forms resembled common staphylococci, diphtheroids, fungi, viruses, and host cell inclusions. Yet if the germ were studied carefully through all its transitional stages, it could be identified as a single agent. She was the first to suggest that the acid-fast stain was the key to the identification of the cancer microbe in tissue and in culture; and also demonstrated its appearance in the blood of cancer patients, by use of dark-field microscopy.

Anyone who takes the time to read Livingston’s reports in the medical literature will quickly recognise that she was a credible research scientist, who allied herself with other experts – and was certainly not the quack doctor pictured by her detractors. Her achievements in cancer microbiology can also be found in her autobiographical books: Cancer, A New Breakthrough (1972); The Microbiology of Cancer (1977); and The Conquest of Cancer (1984). Her research has been confirmed by other scientists, such as microbiologist Eleanor Alexander-Jackson, cell cytologist Irene Diller, biochemist Florence Seibert, and dermatologist Alan Cantwell, among others.

The Cancer Microbe And Bacterial Pleomorphism

Microbiologists have long resisted the idea of bacterial pleomorphism, and do not recognise or accept the various growth forms and the bacterial ‘life cycle’ proposed by various cancer microbe workers. Most bacteriologists do not accept the idea of a bacterium changing from a coccus to a rod, or to a fungus. Depending on the environment, the microbe in its cell wall-deficient phase may attain large size, even larger that a red blood cell. Other forms are submicroscopic and virus-sized. Electronic microscopic studies and photographs of filtered (bacteria-free) cultures of the cancer microbe show virus-size elements of the cancer microbe that can revert into bacterial-sized microbes.

The cancer microbe has adapted to life in man and animals by existing in a mycoplasma-like or cell wall deficient state. In tissue sections of cancer stained for bacteria with the special acid-fast stain, the microbe can be seen as a variably acid-fast (blue, red, or purple-stained) round coccus or as barely visible granules. At magnifications of one thousand times (in oil), these forms can be observed within and also outside of the cells.

Careful study and observation of the tiny round coccoid forms in cancer tissue indicate they can enlarge progressively up to the size of so-called Russell bodies, which are well-known to pathologists. Russell bodies can attain the size of red blood cells, and even larger.

William Russell was a well-respected Scottish pathologist who in 1890 first reported the finding of ‘cancer parasites’ in the tissue of all the cancers he studied. However, modern pathologists deny that Russell’s bodies are microbial in origin. For more information on Russell bodies and Russell’s ‘cancer parasite’ (and its intimate relationship to cancer microbes), Google: The forgotten clue to the bacterial cause of cancer; or go to www.joimr.org/phorum/read.php?f=2&i=50&t=50.

Overlooking Hidden Bacteria In Cancer

Once bacteria were eliminated as a cause of cancer a century ago, it became dogma and impossible to change medical opinion. In this current era of medical science, one would think it impossible for infectious disease experts and pathologists to not recognise bacteria in cancer. However, bacteria can still pop up in diseases in which they were initially overlooked.

When a new and deadly lung disease broke out among legionnaires in Philadelphia in July 1976, two hundred and twenty-two people became ill and thirty-four died. The cause of the killer lung disease remained a medical mystery for over five months until Joe McDade at the Leprosy Branch of the CDC detected unusual bacteria in guinea pigs experimentally infected with lung tissue from the dead legionnaires. Further modification of bacterial culture methods finally allowed the isolation of the causative and previously overlooked bacteria, now known as Legionella pneumophila.

Yet another example of dogma-defying research is provided by recent studies proving that bacteria (Helicobacter pylori) are a common cause of stomach ulcers, which can sometimes lead to stomach cancer and lymphoma. For a century, physicians refused to believe bacteria caused ulcers because they thought bacteria could not live in the acid environment of the stomach. In 2005 the Nobel Prize in Medicine was awarded to two Australian researchers for their 1982 discovery. These stomach bacteria could only be detected by use of special tissue stains. The CDC now claims that H. pylori causes more than 90% of duodenal ulcers and 80% of gastric ulcers. Approximately two-thirds of the world’s population is infected with these microbes.

In the past four years there have been medical reports of newly discovered bacteria in serious lymph node disease; in Hodgkin’s lymphoma; in cancer of the mouth; and in prostate cancer, to name only a few.

All these studies prove bacteria can pop up in diseases where they are least expected. Such a caveat is appropriate for doctors who think they know everything about cancer and who pooh-pooh all aspects of cancer microbe research.

A Century Of Cancer Microbe Research

Livingston never claimed that she was the discoverer of the microbe of cancer. In her writings she always gave credit to various scientists, some dating back to the nineteenth century, who attempted to prove that bacteria cause cancer. Some of these remarkable researchers include the long-forgotten cancer microbe studies of Scottish obstetrician James Young, Chicago physician John Nuzum, Montana surgeon James Scott, the infamous psychiatrist and cancer researcher Wilhelm Reich, microscopist Raymond Royal Rife, and others too numerous to mention.

This cancer microbe research has been explored in my books The Cancer Microbe: The Hidden Killer in Cancer, AIDS, and Other Immune Diseases (1990) and in Four Women Against Cancer: Bacteria, Cancer, and the Origin of Life (2005) – the story of Livingston, Alexander-Jackson, Diller and Seibert – four outstanding women scientists who attempted to bring the cancer microbe to the attention of a disinterested medical establishment. I was privileged to have met all these remarkable women, who greatly influenced my own cancer research.

Why is research exploring bacteria in cancer so strongly opposed? Perhaps it poses a threat to the money interests involved in the established and orthodox treatment for cancer. Various forms of cancer treatment include surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. These therapies might have to be reevaluated if it were proven that cancer was an infectious disease.

Suggestions For Further Study

Further information pertaining to cancer microbe research (both pro and con) can be found by Googling: cancer microbe; bacterial pleomorphism; cell wall deficient bacteria; “alan cantwell”; “virginia livingston”; “Eleanor Alexander-Jackson”; as well as other names and key words mentioned in this communication.

For a list of scientific publications pertaining to the microbiology of cancer, go to the PubMed website hosted by the National Institute of Health (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and type in “Cantwell AR”, “Livingston VW”, “Alexander-Jackson E”, “Diller IC”, “Seibert FB”, etc. in the search box.

This short communication is unlikely to convince many health professionals that bacteria cause cancer. However, after four decades of studying cancer microbes in cancerous tissue, I am personally convinced that Dr. Virginia Livingston will one day be vindicated and recognised as one of the greatest medical geniuses of the twentieth century.

Ralph W. Moss, cancer advocate and author of The Cancer Industry, notes her passing was “a major loss to the cancer world.” In the Cancer Chronicles #6, 1990, he writes, “Virginia Livingston was a great person and a great scientist. Sadly, she never received the recognition she deserved in her lifetime. The true scope of her achievements will only become known in years to come.”

This report honours the centennial of her birth which takes place on 28 December, 2006.

Bibliography

Alexander-Jackson E. A specific type of microorganism isolated from animal and human cancer: bacteriology of the organism. Growth. 1954 Mar;18(1):37-51.

Cantwell AR. Variably acid-fast cell wall-deficient bacteria as a possible cause of dermatologic disease. In, Domingue GJ (Ed). Cell Wall Deficient Bacteria. Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1982. Pp. 321-360.

Cantwell A. The Cancer Microbe. Los Angeles: Aries Rising Press; 1990.

Cantwell A. Four Women Against Cancer. Los Angeles: Aries Rising Press; 2005.

Diller IC, Diller WF. Intracellular acid-fast organisms isolated from malignant tissues. Trans Amer Micr Soc. 1965; 84:138-148.

Greenberg DE, Ding L, Zelazny AM, Stock F, Wong A, Anderson VL, Miller G, Kleiner DE, Tenorio AR, Brinster L, Dorward DW, Murray PR, Holland SM. A novel bacterium associated with lymphadenitis in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. PLoS Pathog. 2006 Apr;2(4):e28. Epub 2006 Apr 14.

Hooper SJ, Crean SJ, Lewis MA, Spratt DA, Wade WG, Wilson MJ. Viable bacteria present within oral squamous cell carcinoma tissue. J Clin Microbiol. 2006 May;44(5):1719-25.

Nuzum JW. The experimental production of metastasizing carcinoma of the breast of the dog and primary epithelioma in man by repeated inoculation of a micrococcus isolated from human breast cancer. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1925; 11;343-352.

Russell W. An address on a characteristic organism of cancer. Br Med J. 1890; 2:1356-1360.

Russell W. The parasite of cancer. Lancet. 1899;1:1138-1141.

Sauter C, Kurrer MO. Intracellular bacteria in Hodgkin’s disease and sclerosing mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: sign of a bacterial etiology? Swiss Med Wkly. 2002 Jun 15;132(23-24):312-5.

Scott MJ. The parasitic origin of carcinoma. Northwest Med. 1925;24:162-166.

Seibert FB, Feldmann FM, Davis RL, Richmond IS. Morphological, biological, and immunological studies on isolates from tumors and leukemic bloods. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1970 Oct 30;174(2):690-728.

Shannon BA, Garrett KL, Cohen RJ. Links between Propionibacterium acnes and prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2006 Apr;2(2):225-32. Review.

Wuerthele Caspe-Livingston V, Alexander-Jackson E, Anderson JA, et al. Cultural properties and pathogenicity of certain microorganisms obtained from various proliferative and neoplastic diseases. Amer J Med Sci. 1950; 220;628-646.

Wuerthele-Caspe Livingston V, Livingston AM. Demonstration of Progenitor cryptocides in the blood of patients with collagen and neoplastic diseases. Trans NY Acad Sci. 1972; 174 (2):636-654.

Young J. Description of an organism obtained from carcinomatous growths. Edinburgh Med J. 1921; 27:212-221.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.