Much of medical science deals strictly with the body, while denying – or at least largely relegating to the background – our inner soul essence. This view is particularly prevalent in conventional vision treatment where eyesight is considered to be a camera-like process which creates an image that’s either in or out of focus. Such a one-tiered approach results in a lopsided notion of what is normal. Eyeglasses are so commonplace in our culture, they’re considered virtually natural extensions of the human anatomy. People seeing clearly with their own eyes are becoming a rare breed.

In more recent years, the quest for a novel approach to vision treatment took a technological leap with the advent of refractive eye surgery, also known as laser eye surgery, or by the acronym of LASIK, a popular procedure. In a way, this technology is turning full circle back to Mother Nature’s design, touting 20/20 vision (or very close to it) with a natural appearance and no fuss. According to the industry, these purported outcomes involve minimal risk and have high patient satisfaction rates.

However, more cases of patients with negative outcomes – ranging in scale from continual annoying symptoms to disabling complications and worsening eyesight – are coming to the forefront in the media and on the Internet. Tragically, a few cases have ended in suicides.The furore prompted the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) last year to publicly hear statements from affected patients. The FDA panel reiterated that refractive eye surgery, like any surgery, has its risks but has an excellent overall track record. Nevertheless, to bolster the safeguards, they recommended enhanced patient screening methods and further post-operative studies by the industry. (Interestingly, the eye doctor who chaired the FDA panel wears glasses. Although she regularly performs refractive eye surgery, she chooses not to undergo the procedure herself, citing one of the reasons as an aversion to any level of risk.)

Lost amid the allure and debates over technological treatments is an obscure alternative called natural vision improvement (NVI). As the name implies, it’s a more nature-centred approach, a holistic mind-body method that seeks to reverse an imbalance induced by a response to stress. It introduces a psychological component, counter to most prevailing notions that the physical eyes somehow just “go bad” with no hope of improving. For those attuned to esoteric traditions – or the “Perennial Philosophy” as writer Aldous Huxley put it – the psyche is simply a secular name for the soul.

To understand how NVI succeeds on the personal soul level, the work of spiritual scientist Rudolf Steiner offers some insights. While embodied within a physical form, our soul is said to be a link between the “lower” physical world and the “higher” world of the spirit in which we simultaneously participate. Steiner further suggested that a portion called the sentient soul is responsible for our experience of sensation. He also distinguished between the terms perception and sensation; perception comes first and is fleeting, but the sensation which follows lasts.

When external light reaches us, the eyes initially register myriad perceptions from our environment. Then something lights up in the sentient soul when certain perceptions are filtered and sensations come alive with personal vividness and quality. For example, when you behold a red object with your eyes, you initially perceive the colour. However, this colour perception ceases once you look away, but the sensation that it makes upon you continues to linger in your soul. It’s a lasting impression that may be later recalled, whether to ponder its meaning and significance or to rekindle nostalgic sentiments and feelings.

Because our sensations illuminate internally in a unique and private way, Steiner contended that this soul activity is not a mere brain process. Science can describe the various light, chemical and nerve stimuli along the chain from the eye retina to the brain, but he noted that nowhere can our actual sensations be found in this chain. The sentient soul is said to also partake in the intrinsically private activities of feelings, emotions, drives and instincts, as well as willing, where our soul flows outward through actions.

Such a perspective of soul activity aligns with other researchers’ distinctions of mind and brain. Neurophysiologist Wilder Penfield once determined that no amount of electronic probing in the various areas of the brain would elicit a person to believe or decide. He concluded that the mind seems to work independently of the brain, analogous to a computer programmer acting independently of the firings within the computer. Penfield suggested that the mind has its own energy that is different from the neurons that travel the pathways within the brain.

Michael Polanyi, philosopher of science and social science, arrived at the same conclusion when he stated that thoughts and neural processes are two completely different things.

Religious author Huston Smith concurs, suggesting “the brain breathes mind like the lungs breathe air.”

We typically think of having five senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch – with sight generally considered to be the most important in its ability to perceive shades of lightness and different colours. However, Steiner recognised that we have at least seven more than these basic senses. By the term sense, he meant a perception which provides us with immediate information without the involvement of a thought process. One of the additional senses he noted was what he called movement, what is nowadays termed proprioception. Movement is that special sense which indicates whether we’re still or moving, providing direct feedback where our joints, tendons and muscles are in space.

Steiner also recognised how the various senses work together, not in isolation. Although each sense may be categorised for the sake of definitions, our soul reunites the separate perceptions into a unified whole that provides coherent inner meaning. Of particular note, he was well aware that vision encompasses more than the sense of sight. In 1919, he knew the important role that the sense of movement plays in visual sensation:

We nearly always see things so that when they give the colours to us, they also show us the boundaries of colours, namely, lines and forms. We are not normally aware of how we perceive when we perceive colour and form at the same time…. At first you see only the colour through the specific activity of the eye [sense of sight]. You see the circular form when you subconsciously use the sense of movement and unconsciously make a circular movement… When the circle you have apprehended through your sense of movement rises to cognition, it is then joined with the perceived colour. You take the form out of your entire body when you appeal to the sense of movement spread out over your entire body…. Today, official science is not at all interested in such a refined way of observation, so it does not distinguish between seeing colour and perceiving form with the help of the sense of movement… In the future, however, we will not be able to educate with such confusion. How will it be possible to educate human seeing if we do not know that the whole human being participates in seeing through the sense of movement?

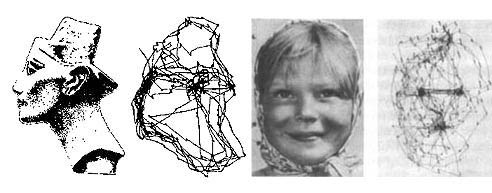

Decades later, Steiner’s comments appear to have been validated by Alfred Yarbus, a psychologist who studied the eye movements of people looking at natural objects and scenes. In the 1950s and 1960s, he recorded the rapid saccadic eye movements that occur within milliseconds and demonstrated with remarkable images how the eyes subconsciously scan forms and outlines with incredible speed. Figure 2 has examples from Yarbus’ work.

Figure 2 – The sense of movement in vision. Rapid eye tracing movements corresponding to images viewed (Yarbus, 1967).

Steiner’s observations are also quite extraordinary when related to NVI fundamentals of proper vision. William Bates was an eye doctor who broke from the mold of orthodox teachings and single-handedly established the field of NVI back in the early 1900s. Two of Bates’ guiding fundamentals are what he called shifting and apparent movement (also called the swing), both which involve our sense of movement.

The eyes, which move by different sets of surrounding muscles, must continually shift from point to point to prevent the strain of fixation. Otherwise, the subconscious saccadic movements become sluggish and vision begins to blur within seconds. It’s analogous to grasping a heavy object in your hand and holding it tightly in an extended arm position. The muscle strain cannot be held long before you lose your hold and drop the object. If we fixate for too long in an attempt to “hold” a point in our sight with intense concentration, the effort backfires and we lose the clarity of sight.

As for oppositional movement, stationary objects in our peripheral field of vision must have the appearance of moving in an opposing direction. This swing is a natural consequence of the first fundamental, the shift.

Bates explains the illusion of the swing: “Your head and eyes are moving all day long. Imagine that stationary objects are moving in the direction opposite to the movement of your head and eyes. When you walk about the room or on the street, notice that the floor or pavement seems to come toward you, while objects on either side appear to move in the direction opposite to the movement of your body.”

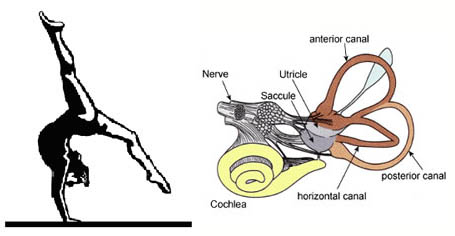

If one attempts to stop this illusion of oppositional movement, Bates claimed it caused vertigo or dizziness. That’s because our sense of balance also comes into play for effective vision. Coordinated body movements and eye movements depend on good balance, controlled by the organs in the inner ears.

In more recent years, the role of movement and balance in visual perception has been recognised in a speciality field called developmental or behavioural optometry. They have made the connection between visual difficulties, mental development, and emotional behaviour, with such problems as dyslexia, slow reading and poor comprehension, ADHD and juvenile delinquency. Some children have difficulty reuniting the individual senses as a unified whole, causing a jumbled imbalance of sensations, thoughts and emotions.

The importance of training which integrates the senses with whole-body movements is a hallmark of this specialised field of optometry. The training typically incorporates bouncing on the trampoline with rhythmic arm and hand movements and visual interaction with special wall charts. Or the child could be instructed to call out answers to rapid-fire mental tasks – like mathematics or spelling – while jumping on the trampoline. Balance beams are also used in combination with sensory, physical and mental tasks.

In a separate field of study, psychiatrist Harold Levinson treated thousands of cases of learning disabilities and phobias and discovered a common physical correlation. Over 90 percent of his patients who were dyslexic or phobic had a malfunction of the inner-ear system. These more recent findings validate what Steiner suggested back in his day: mental disorders are linked to physiological disorders.

“But one will find over and again,” he wrote, “that especially in so-called mental illness – which actually has been, as such, incorrectly named – physical processes of illness are present in a hidden way somewhere. Before one wants to meddle. . . with mental illness, one ought actually, with the proper diagnosis, to determine which physical organ is involved in the illness.” Thinking, feeling, and willing – soul activities which follow from our senses – are all interrelated and interdependent.

Figure 3 – The sense of balance in vision. The inner ear regulates balanced eye movements.

In our highly technological era, we are intently centred on the physical realm, bombarded with sense data from the external environment. Such sensory overload may induce responses in an individual’s soul, such as fear and anxiety, while causing overconcentration and staring. The net result can lead to a habitual strain pattern that restricts movement and negatively impacts the healthy functioning of the eye-focusing muscles. School age children are especially prone to such problems and begin to develop vision problems early as a result.

One of the most fascinating aspects of improving eyesight naturally is a “flash” of near perfect vision that spontaneously occurs from time to time. I experienced flashes several times prior to having any knowledge of the phenomenon. They appear very early in the vision improvement process for many people, even for those with a high degree of initial blur. I liken the experience to a flash of inspiration or intuition from the spiritual realm, a Divine Perfection pouring into the soul, reminding the eyes how to see clearly again without strain. It’s also a reminder to step back from the stressful demands of a society fixated on material ends and become more in touch with our higher spiritual nature.

Quantum physicist Arthur Zajonc chronicled the scientific study of light and visual optics from the time of the early Greek philosophers to our current age and laments at the gradual demise of artistic and spiritual insights in the endeavour. Throughout the centuries, Plato’s light of the soul in visual perception was eventually excised by science to the point we are today – a pure neurophysical model – even though the nature of light is as enigmatic as ever.

We’ve become so steeped in material pursuits that we’ve “lost sight” of the spiritual side. If physical light is the counterpart of spiritual light, perhaps the visual blur that’s endemic to modern culture is a manifestation of spiritual myopia?

Observe the symmetry in the word “eye” itself. I view it as a symbol of our threefold nature. One “e” represents the exoteric, or physical realm, while the other “e” represents the esoteric, or spiritual realm. The “y” in between is the soul with three branches, two linking body and spirit, while the third points to the “I” (pronounced the same as “eye”) that is the centre of our soul. Window of the soul, indeed!

Bibliography

William H. Bates, The Cure of Imperfect Sight by Treatment Without Glasses, New York: Central Fixation Publishing, 1920. Reprint, Pomeroy, Wash.: Health Research Books, n.d.

William H. Bates, “Perfect Sight,” Better Eyesight, September 1927

Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1945

LASIK Complications website, www.lasikcomplications.com

Harold N. Levinson, Phobia Free, with Stephen Carter, New York: M. Evans and Company, 1986

Wilder Penfield, The Mystery of the Mind: A Critical Study of Consciousness and the Human Brain, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975. Quoted in Huston Smith, Forgotten Truth: The Common Vision of the World’s Religions (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 64-65

Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958. Quoted in Huston Smith, Forgotten Truth: The Common Vision of the World’s Religions (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 63

Huston Smith, Forgotten Truth: The Common Vision of the World’s Religions, New York: Harper Collins, 1992

Rudolf Steiner, A Psychology of Body, Soul, and Spirit: Anthroposophy, Psychosophy, & Pneumatosophy, Translated by Marjorie Spock, Herndon, Va.: Anthroposophic Press, 1999

Rudolf Steiner, Polarities in Health, Illness and Therapy, Lecture, Pennmenmawr, N. Wales, August 28, 1923. Spring Valley, NY: Mercury Press, 1987. Rudolf Steiner Archive. wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/Polart_index.html

Rudolf Steiner, The Foundations of Human Experience, Translated by Robert F. Lathe and Nancy Parsons Whittaker, Herndon, Va.: Anthroposophic Press, 1996

Rudolf Steiner, Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos, Translated by Catherine E. Creeger. Herndon, Va.: Anthroposophic Press, 1994

Alfred Yarbus, Eye Movements and Vision, New York: Plenum Press, 1967

Arthur Zajonc, Catching the Light: The Entwined History of Light and Mind, New York: Bantam Books, 1993

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.