From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 12 No 1 (Feb 2018)

In 1904 the British geographer Halford Mackinder addressed the Royal Geographical Society in London.1 He advanced a geopolitical theory that is now known as the “Heartland Theory.” Mackinder divided the world into three major regions: the “World Island” comprising the continents of Africa, Asia and Europe; the “Offshore Islands,” which included the UK and Japan; and the “Outlying Islands” which included the North and South American continents and Australia.

At the centre of the World Island was an entity he described as the “Heartland”; an arc stretching from the Volga (in modern Russia) to the Yangtze in China. That is the region we now describe as Eurasia. After World War I, Mackinder summarised his theory in these terms:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland.

Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island

Who rules the World Island commands the world.2

The world was a very different place in 1904. Russia was a feudal monarchy; China was weakened by colonial occupation and exploitation; most of Africa was ruled by European colonial powers; and the US was yet to emerge as a significant military and geopolitical force.

The hundred years following Mackinder’s presentation to the Royal Society saw unprecedented change in the world’s geopolitical structure. Two world wars, the Bolshevik Revolution, the decolonisation of Africa and Asia, the relative collapse of European colonial imperial power and the rise of an aggressively expansionist United States, saw a fundamental shift of power in the period from 1914 to 1990. As will be argued, the explanatory power of Mackinder’s vision is an effective tool for understanding contemporary geopolitical structures and the likely course of future events.

The seeds of US foreign policy, which dominated the past several decades, were planted in the 19th century. In 1853 a US naval convoy under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Harbour. On behalf of the US government, Perry demanded a treaty with Japan that would allow trade between Japan and the United States. Japan had no navy and was forced to acquiesce to the American demands. A treaty was duly signed permitting trade and opening Japanese ports to US merchant shipping.

A similar exercise in gunboat diplomacy occurred in 1866 when the USS General Sherman steamed up the Taedong River in an attempt to open up Korea to trade by force. The attempt was repelled, but a US flotilla returned five years later and attacked Korean forts. Although the Americans withdrew after inflicting heavy losses, traditional Korean society was weakened, and within a few years Korea had been forced into unequal treaties with Japan, the US, Britain, Russia and other countries.3

World War II wrought devastating losses on the two powers that might have been able to challenge American post-war hegemony – Russia and China. They each lost between 25 and 30 million people fighting off the German and Japanese invasions respectively.

The scale of these losses is scarcely acknowledged in the Western popular media. Countless films, books and TV programs inculcate images of a heroic British empire fighting alone until Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the Americans into the war. The British element of the war was then fought in a long slog across North Africa, Italy, and then with the Americans in Italy and the D Day landings of June 1944. The Americans fought the Japanese across the Pacific, island by island.

Total British casualties in World War II (civilian and military) were 451,000. American losses, primarily military, were 419,000. Total Canadian, Australian and New Zealand casualties were 106,000. To put those numbers into perspective, Russia had 1.1 million casualties in the Battle of Stalingrad (July 1942 to January 1943) alone.

China’s war with Japan began in 1937 and continued until August 1945. Accurate statistics are hard to come by, but the number of civilian deaths is variously placed at between 10 and 25 million, and up to four million military deaths.4 Clearly, once again, these deaths dwarf Western-allied casualties, but there is even less acknowledgment in the Western media than is the case with Russia.

These figures are mentioned because the scale of those casualties has exerted a dominant influence over Russian and Chinese strategic thinking ever since. It is impossible to understand modern geopolitical structures without appreciating how both governments are driven to avoiding being placed in that position again.

Full Spectrum Dominance

The end of World War II did not see the end of military action by the West. The US, in particular, has sought to exercise a level of control over nations around the world that is best encapsulated in the doctrine of “full spectrum dominance.”5 By this, it was intended that the US would be without military parallel at sea, on the land, in the air, and in cyberspace.

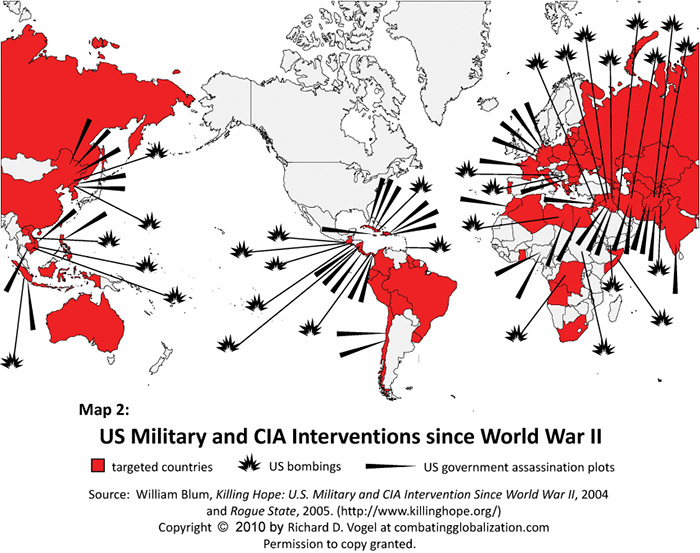

In pursuit of that doctrine, the US has since World War II invaded, occupied, bombed and/or overthrown the governments of 70 nations, killing between 30 and 40 million people in the process.6

Its troops currently occupy or are fighting in, either directly or through proxies, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. None of these wars have any legitimacy in international law, the defiance of which is a dominant characteristic of US foreign policy.7 In addition to direct military intervention, the US is a major sponsor of hybrid warfare on every continent.8

The experiences of Russia and China have been very different. After World War II, the Soviet Union occupied those Eastern European countries it had captured from German occupation or who were part of the Axis coalition during the war. Western propaganda persistently portrayed that occupation as evidence of a Soviet desire to conquer the world. It is more accurately viewed as the creation of buffer states to insulate Russia from further Western invasions. That invasion history did not begin with the German invasion in July 1941.9

The agreement between Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and Bush the Elder that allowed the reunification of the two parts of Germany had been accompanied by a pledge by the Americans that NATO would “not advance one inch further east.”10 The subsequent history of Eastern Europe is a perfect illustration of why American assurances are not to be trusted.

Despite there now being foreign troops stationed on Russia’s borders, the installation of missile systems directed at Russia, and the regular carrying out of large-scale military exercises, again clearly aimed at Russia, it is Russia that is portrayed in the Western media as being aggressive. It is this capacity for hypocrisy and doublethink that again is a prominent feature of Western policy.

In 1990 the Soviet Union collapsed. That collapse was followed by a disastrous decade under Yeltsin when Russia’s resources were plundered by homegrown oligarchs and Western corporations. Life expectancy fell and living standards plummeted. Yeltsin was succeeded by Vladimir Putin who has achieved a miraculous turnaround in Russia’s fortunes.11 It is this, more than any other single factor, which probably explains the constant demonisation of Putin by the American media.12

China’s Experience

China’s post-war history was also disruptive. After the Japanese had been defeated, the civil war resumed, concluding with victory under Mao in 1949. The Korean War commenced the following year, and it was US General McArthur’s threat to cross the Yalu River that brought China into that war. We now know that the Americans seriously considered the use nuclear weapons on China.13

That war was barely concluded when Mao embarked on his Great Leap Forward (da yue jin) program (1958–1962). Although intended to transform China from an agrarian to an industrial society, it was in many respects a disaster. Widespread famine was one consequence. Internal party criticism of Mao by people such as Deng Xiaoping led to Mao’s marginalisation within the Party. The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was aimed at restoring Mao’s control, but it had disastrous consequences on China’s economy and society. It was Deng Xiaoping, who led China from 1978 until 1989 with his “four Modernisations” first proposed by Zhou Enlai in 1963, that began the transformation of China into its current status. Those four pillars of modernisation were agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology.

Ever since China has sustained a level of development unparalleled anywhere in the world. More than half a billion people have been lifted out of poverty into the middle class. Huge infrastructure developments including more high-speed rail than the rest of the world combined, and the development of centres of technological excellence as in the transformation of Shenzhen from a small fishing village to a world-class centre of excellence in less than 40 years. Shenzhen is one of China’s Special Economic Zones where investment strategies owe more to entrepreneurial capitalism than they do to the outmoded depiction of China as a communist nation.

On the basis of parity purchasing power, China’s economy is now larger than that of the United States, and the disparity grows wider every day. The United States did not have anything as dramatic as the collapse of the Soviet Union or the transformation of China, but it did have a geopolitical event, the consequences of which have profoundly affected the direction of US policy, and contributed to a rebalancing of the world’s geopolitical structure.

The Geopolitical Event of 9/11

That event was the attacks within the United States of 11 September 2001 (‘9/11’). These attacks were attributed to 19 Muslim hijackers directed by Osama bin Laden from his cave in Afghanistan. It is outside the scope of this article to discuss those events and the official explanation that rapidly emerged and was reinforced by the Report of the 9/11 Commission.14 Suffice to say for present purposes that the US government’s version of events is completely unsupported by the scientific evidence, as has been conclusively demonstrated in a number of excellent studies.15

The significance of 9/11 for present purposes is that it provided the springboard for a sustained attack by the US and its coalition allies, including Australia, upon a number of countries. Afghanistan was the first victim; falsely attributed with harbouring the alleged mastermind of 9/11, bin Laden, and refusing to hand him over for “justice.”16 We now know, for example, that the decision to invade Afghanistan was made in July 2001. The real motives had nothing to do with bin Laden.17

Afghanistan was followed by Iraq in 2003, Libya in 2011 and Syria in 2014, among many other targets. They all had a common theme. All were based upon lies of one sort or another, and none of them had any basis in international law. All were justified in the name of being part of a “war on terror” which, apart from being singularly ironic coming as it does from the world’s greatest perpetrator of terror by a considerable margin,18 provided a perfect smokescreen for the erosion of civil liberties,19 the exploitation of foreign resources,20 the massive expansion of the military budget, and a continued expansion of what was already a worldwide network of bases.21

The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq may have seemed successful at first, but the longer the occupation continued (now 16 and 14 years respectively) the greater the destruction of those societies and the greater the internal resistance. On the positive side, there has been a growing realisation, including in Australia, that there has to be a better alternative to the relentless destruction and plundering that has marked the “American century.”

What has transpired, especially in the past 16 years, is a geopolitical realignment that has given fresh impetus to Mackinder’s prescient view of the emergence of the “Heartland,” that is, Eurasia, as the focus and dynamic centre for the 21st century.

A Coming Together in the Heartland

To facilitate this development a number of organisations and agreements were established. Most of these, until very recently, have flown under the radar of the Western media. The first, chronologically, was the Eurasian Economic Community, a grouping of six former members of the Soviet Union, with Russia the largest and most economically and politically important member. This evolved into the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in 2010 and currently incorporates the six original members. Its focus is on interregional trade and investment and moving toward a common currency zone.

More recently, the EAEU has begun forming links outside the original six with other trading groups and also individual countries. Of these, the most significant is Turkey, which in 2017 began negotiating a free trade deal with the EAEU and talking about possible future membership. This is significant as it marks the final disenchantment of Turkey with the European Union with whom it has been holding negotiations for the past 30 years without obvious progress.

Turkey is also a member of NATO and its reorientation to the East has further ramifications. Turkey recently signed a multibillion-dollar deal with Russia to be supplied with the Russian S400 antimissile defence system, much to the consternation of the Americans whose own missile defence system is inferior to the Russian version, but who have always seen NATO as providing a captive market for its own military sales.

In March 2017 the prime ministers of Iran and the six EAEU member states signed cooperation agreements, and further integration is anticipated. Russia has also sold its S400 system to Iran and Iran has provided an airbase for the Russian military at Hamadan, located 47 km from the city of the same name.

Iran is also a key link in the North South Transportation Corridor (NSTC) that links India with Russia via Iran and Azerbaijan. To facilitate the NSTC and the other developments discussed below, Iran is investing in major infrastructure projects with the financial and technical assistance of Russia and China. This notably includes upgraded rail linkages.

Iran also made a recent agreement with Qatar to jointly develop the huge natural gas resources in the Persian Gulf, known as the South Pars field in Iran and the North Dome field in Qatar. This agreement was a major factor in the recent threats, demands and economic moves against Qatar made by Saudi Arabia, from which the Saudis have largely resiled.

Another important factor in the Saudi-Qatar dispute was the decision by Qatar to sell $50 billion of natural gas to China, the key fact being that the deal was not denominated in US dollars. It was an important milestone in the disappearance of the petrodollar,22 a fact of more significance to the US on whose behalf Saudi Arabia was undoubtedly acting.

Another grouping is BRICS, an acronym coined in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, chairman of Goldman Sachs, with the initials representing the (original) four countries of Brazil, Russia, India and China. The ‘S’ represents South Africa that did not join until 2010. The first meeting of the BRIC nations was in 2006 at Foreign Minister level with the first full-scale conference in Yekaterinburg, Russia, in June 2009.

BRICS is significant not only for its membership, representing as it does a significant percentage of the world’s population and GDP, and not only its geographical spread, but also that it is taking increasing steps to separate itself from the US and European dominated World Bank and IMF by setting up its own development bank. It is also instrumental in setting up CHIPS, an alternative to SWIFT, the interbank trading system that has been used as a tool in imposing financial sanctions on, among others, Iran and Russia. Those sanctions have been a form of financial imperialism.

Arguably the most important grouping, however, is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the details and significance of which is almost entirely absent from most Western media analysis. The SCO was formed in 2001 and initially comprised China and Russia, plus Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. It had six Observer States and six Dialogue Partners.

Iran is an Observer State and has applied for full membership, with the strong backing of Russia. It is likely to become a full member in 2018.

Two other Observer States that achieved full membership in July 2017 were India and Pakistan. Egypt and Syria have applied for Observer State status, and another Observer State, Turkey, has applied for full membership. Afghanistan is another Observer State, although its attempts to have a fuller level of cooperation with other SCO members and benefit from infrastructure investment have been blocked by the US. President Trump has openly stated that Afghanistan’s significant natural resources, estimated by the US geological survey in 2012 at up to $3 trillion, should be exploited by the US.23 Significantly, that resource includes more than one million tonnes of rare earth elements, a key component of modern technology.24

The US is unlikely to relinquish its role in Afghanistan any time soon as, apart from its mineral wealth, it provides 93% of the world’s heroin25 of which the US is a significant beneficiary,26 and has military bases designed to form part of its containment policy of China. [As of April 2021, the US announced it was finally going to withdraw from Afghanistan. We are yet to learn the exact details of what that really means including how many US private contractors stay on and how many troops remain to protect military bases.]

The US has also, since at least Operation Cyclone in the 1970s, used Afghanistan as a springboard for the infiltration of Muslim extremists into Iran, China and Central Asia as part of its hybrid warfare role in the destabilisation of those countries.27

Perhaps, needless to add, none of these facts form part of the Western narrative with regard to Afghanistan, particularly in Australia, that prefers to perpetuate its myth of being there in a “training and advisory role.”28 A role that after 16 years has been spectacularly unsuccessful in achieving anything approaching positive results.

Since 2004 the SCO has also had a security cooperation component (CSTO) aimed at coordinating responses by SCO members to security (including terrorist) threats to member states. Other areas of focus include combatting drug trafficking, organised crime and religious extremism. Unlike NATO, SCO does not need an external enemy to justify its existence. Covering a quarter of the world’s population and three-fifths of the Eurasian landmass, it again provides an alternative model for tackling common problems, many of which are generated outside its borders.

The reader will have noted that BRICS, the EAEU, the NSTC and the SCO have considerable overlapping memberships. While that is not without its problems, as with the recent confrontation of India and China over the Donglang region of the China-Bhutan border and elsewhere on their common frontier, these problems have thus far been resolved without resort to war. Dialogue has been the key, a factor notably lacking with the US in, for example, Afghanistan and Korea.29

One Belt One Road: Will Australia Ruin its Continued Prosperity?

Towering over all these developments, however, is a project that is transforming Eurasia in its scope and ambition. It is the world’s largest infrastructure project by a significant margin. Publicly announced by China’s President Xi Jinping in 2014, it’s been variously described as the New Silk Roads, One Belt One Road (Yi dai Yi lu) (Xi’s original description) and its current nomenclature, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). I have previously discussed this project in New Dawn30 and will not repeat that here.

As may be seen from the various graphic representations, the BRI has both land and maritime components, linking Eurasia with Africa and South America. Its land component is a combination of road, high-speed rail and fibre optic communications. One illustration is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), itself a $50 billion project linking China with the Pakistan port of Gwadar.

Among its many virtues, CPEC bypasses the narrow Strait of Malacca through which more than 80% of China’s oil imports currently pass. Australia regularly joins with the US in an exercise, Operation Talisman Sabre, that practices blockading the Malacca Strait. Unsurprisingly, this is seen as an unfriendly act by China. Australian governments seem not to appreciate that the countries (now more than 60) that have joined the BRI also produce the same commodities that Australia has grown rich on selling to China over the past 50 years. If Australia persists in its unfriendly acts towards China, for example by joining with the Americans in hostility toward China over Korea and the South China Sea, then the day will surely come when China switches its preferred suppliers from Australia to friendlier nations reachable by high speed rail.31

Looked at from a broader perspective, American military misadventures since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan may be seen as symptomatic of the disintegration and collapse of the American empire. Ironically, this has been recognised by the Pentagon itself, as detailed in a recent study.32 Their proposed “solution,” however, is more of the same policies that led to America’s decline in the first place: more surveillance; more strategic manipulation of perception (i.e. propaganda); and more military interventions. The contrast with President Xi’s “win-win” philosophy and his geopolitical analysis outlined in Switzerland in 201733 could not be greater.

How likely is it that the US empire will collapse and be replaced by, at the very least, a multi-polar alternative world? The American historian Alfred McCoy in his latest book34 sees the decline in the US’s ability to retain global hegemony as attributable to a number of factors. One important factor is the decline in US educational standards resulting from years of underinvestment as crucial spending was subsumed to the needs of an ever more bloated military establishment. The F35 debacle is a classic metaphor for all that is wrong with military investment and an inability to produce a quality product.

Another factor that McCoy identifies is the dollar’s disappearance as the world’s sole reserve currency; a status that has enabled the US to live beyond its means for decades. The de-dollarisation of the world is growing rapidly, not least as noted above in the Eurasian trading blocs and separate deals (e.g. Qatar) outside those blocs. Trading is increasingly in local currencies like the Ruble or Yuan, or through constructs such as Special Drawing Rights or gold based convertible notes.35 China’s increasing economic dominance will accelerate that trend.

The new world order that is emerging is fulfilling Mackinder’s vision of 114 years ago. For the reasons set out above, Russia and China are central to that realignment. Ironically, the Russophobia of America’s Deep State and their fundamental inability to grasp the nature and the consequences of the re-emergence of Chinese power has expedited the strategic relationship between these two powers.

The US will undoubtedly continue to strive to undermine the Eurasian partnership through a range of manoeuvres. Its provocative conduct in the South China Sea; its bellicosity to North Korea; its trouble making between China and India; its conduct in Ukraine and elsewhere in Eastern Europe; and its continuing addiction to hybrid warfare show no signs of abating.

The fundamental fact of the 21st century is that the US no longer has the power to impose its will as it was largely able to do from 1945 to 2000. A new model, centred on the World Island Heartland is taking shape, with China and Russia as its major drivers.

Footnotes

1. H. Mackinder, The Geographical Journal, April 1904

2. Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction(1919)

3. P. Duus, The Abacus and the Sword: the Japanese Penetration of Korea, University of California Press (1998); Y-L Chung, Korea Under Siege 1876-1945, OUP (2005)

4. R Rummel, China’s Bloody Century, Transaction (1991)

5. US Department of Defence, Joint vision 2020 (2000)

6. W. Blum, Killing Hope (2008); Blum, America’s Deadliest Export: Democracy (2014); Blum, Rogue State (rev.ed) (2016)

7. C. Doebbler, American Hypocrisy in International Law, www.counterpunch.org, 6 March 2014

8. A. Korybko, Hybrid Wars, www.orientalreview.org August 2015

9. D. Stone, A Military History of Russia, Greenwood Publishing (2006)

10. U. Klussmann et al, Did the West Break its Promise to Moscow, www.spiegel.de 26 November 2009

11. S. Djankov, Russia’s Economy Under Putin, www.piie.com, September 2015

12. S. Cohen, Stop the Pointless Demonization of Putin, www.thenation.com, 7 May 2012

13. C. Posey, How the Korean War almost Went Nuclear, www.airspacemag.com July 2015; B. Guertzman, US Papers Tell of 1953 Policy to A-Bomb Korea, www.nytimes.com, 8 June 1984

14. The 9/11 Commission Report, July 2004

15. D. Griffin, Bush and Cheney: How they Ruined America and the World, Olive Branch Press, 2017

16. Ibid.

17. J. O’Neill, Trump and Afghanistan: A Hidden Agenda, www.journal-neo.org, 25 August 2017

18. Blum, op cit. N6

19. T. Stephens, Civil Liberties After September 11, www.

counterpunch.org, 11 July 2003

20. M. Chossudovsky, The War is Worth Waging: Afghanistan’s Vast Reserves of Minerals & Natural Gas, www.globalresearch.ca, 22 August 2017

21. D. Vine, The US Probably has more Bases than any Other People, Nation or empire in History, www.thenation.com, 14 September 2015

22. J. O’Neill, The Demise of the Petrodollar and the New Multipolar World, www.independentaustralia.net, 4 July 2017

23. M. Landler & J. Risen, Trump finds Reason for the US to Remain in Afghanistan: Minerals, www.nytimes.com, 25 July 2017

24. www.newsecuritybeat.org, 27 July 2017

25. UN Office of Drugs and Crime, World Drug Report 2016

26. P. Scott, Drugs, Oil and War: The US in Afghanistan, Colombia and Indochina, Rowman & Littlefield (2004)

27. Z. Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, Basic Books (1998); S. Coll, Ghost Wars, Penguin (2004)

28. J. O’Neill, Myths, Legends and Lies: Australia’s Policy in Afghanistan, www.gumshoenews.com, 26 July 2017

29. US Skips Out on Afghan-Taliban Conference in Moscow, www.dw.com, 14 April 2017

30. J. O’Neill, The New Silk Roads: The Quiet Revolution, New Dawn155 (Mar-Apr 2016)

31. B. Habib & V. Faulkner, The Belt and Road Initiative, www.theconversation.com, 17 May 2017

32. US Army War College, At Our Own Peril (2017)

33. President Xi’s Opening Plenary Speech at Davos, www.

weforum.org, 17 January 2017.

34. A. McCoy, In the Shadow of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of US Global Power, Haymarket Books (2017)

35. K. Rapoza, Much to the Dismay of China Haters the Yuan Goes Global on October 1, www.forbes.com, 30 September 2016; JN. Willie, Gold Trade Note sighted, www.goldseekers.com, 16 February 2017

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.