From New Dawn 171 (Nov-Dec 2018)

The dominant feature of all Australian politics is that governments come and go, with Labor alternating with the Liberal National coalition, but changes in Australian foreign policy are so slight as to be almost invisible.

Not since the Whitlam Government was elected in 1972 and promptly recognised the Beijing government as the proper representative of China, and withdrew Australian troops from the enduring fiasco known as the Vietnam war, but more accurately described by Vietnamese themselves as the American war, has there been a truly bold and principle based foreign policy innovation.

It is one of history’ revealing vignettes that Whitlam’s pre-election trip to China and obvious intention to recognise the PRC as the legitimate government was heavily criticised by Billy McMahon, the Liberal prime minister at the time. McMahon was adhering to what he thought was the Washington line when the United States itself, under Richard Nixon, was already moving to normalise US-China relations. It seems that no one in the United States administration thought to tell McMahon that the policy had changed, thereby exposing McMahon to embarrassment and ridicule.

The Whitlam era was notable for another aspect of foreign policy that Australian historians are loathe to approach, but which arguably has had an impact up to and including the present foreign policy stance of both major political parties.

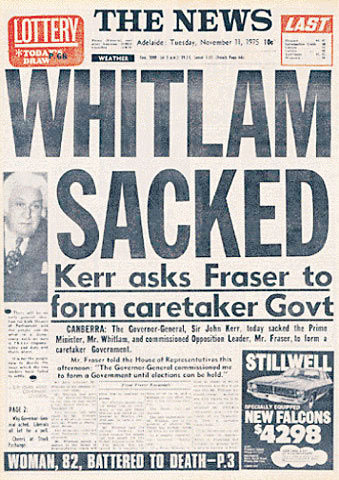

The day before Whitlam was to make a speech in parliament announcing that the United States run spy facility at Pine Gap in the Northern Territory would be closed, he was deposed in a coup d’état by the Governor General Sir John Kerr. That much is common knowledge and has been widely analysed, in particular by historian Jenny Hocking who is engaged in an ongoing battle to access Kerr’s papers, in particular communications between Kerr and the British Queen.

His next role was in Indonesia where he was instrumental in the 1965 coup that brought Suharto to power. Between 500,000 and three million Indonesians were murdered in the coup’s aftermath, many of them from a CIA supplied kill list of communists or suspected communist sympathisers.

Less well known was the role of the United States embassy in Canberra where Marshall Green was the ambassador. Green had an interesting career. He had been assigned to South Korea as charge d’affaires where he organised the 1961 coup that brought the dictatorship of Park Chung-Hee to power.

He was similarly dispatched to Chile where he oversaw the resolution of the ‘problem’ being created for the United States by its left-wing president Allende. Allende was murdered and replaced by a military dictatorship under General Pinochet. Again, hundreds of thousands of Chileans were murdered or ‘disappeared’.

Whitlam posed a similar ‘problem’ for the Americans with his intention to disclose the CIA’s role in Pine Gap. Thanks to Edward Snowden, it is established beyond doubt that Pine Gap is a giant electronic vacuum cleaner, spying on the communications of Australia and a range of other countries, friend and foe alike.

Green, known in State Department and CIA circles as the “coup master,” was sent to Canberra as United States ambassador in 1974, specifically to deal with the Whitlam ‘problem’.

Whitlam was unaware of Kerr’s close ties to the CIA. Neither did he know until 1975 that Britain’s MI6 had been intercepting secret foreign affairs communications for Whitlam’s Office, and passing those onto the Americans.

On 10 November 1975 Whitlam was shown a Telex message later sourced to the notorious Ted Shackley of the CIA that described Whitlam as a security threat to his own country. The following day Kerr used his power to dismiss Whitlam.

It has subsequently become clear that Green, Shackley, MI6 head Maurice Oldfield and CIA head William Colby co-ordinated the dismissal of the Whitlam Government, knowing that they could rely on “their man” Kerr to solve the Whitlam ‘problem’.

My argument is that without knowledge of this historical background it is not possible to fully understand the foreign policy of Australia in subsequent decades.

Not in Australia’s Interest

Time and again Australia has undertaken foreign policy initiatives that if viewed from the perspective of Australia’s vital national interests are simply inexplicable. That process has if anything accelerated in recent years.

In August 1990 Iraq invaded its neighbour Kuwait. Iraq had some legitimate grievances with Kuwait, but the decision to invade, otherwise a blatant violation of international law, was only made after the United States ambassador to Iraq told Saddam Hussein that the United States was not really interested in the argument between Iraq and Kuwait. Saddam took that as a green light.

There followed a massive propaganda campaign against Iraq, perhaps best exemplified by the appearance of a young woman on US television describing how Iraqi soldiers took Kuwaiti babies from their cots in a Kuwait hospital and smashed them on the concrete floor.

That the young woman concerned was the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States (not disclosed to viewers) and that she had witnessed no such thing was only part of the lie.

The Americans assembled a “coalition of the willing” to force the Iraqis to leave Kuwait. Australia was a member of that coalition. The Iraqis were quickly defeated, but that did not prevent the slaughter of the retreating troops. Worse was to come. Sanctions were imposed on Iraq, supported by Australia, resulting in the deaths of more than half a million civilians, including women, children and old persons. This was infamously described by US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright as “worth it.”

In what sense it was “worth it” for Australia to join this war in the first place, to sustain a role in the blockade and sanctioning of Iraq (tempered by dubious Wheat Board dealings), has never been adequately explained.

In 2001 Australia again joined a United States led coalition in the attack upon, invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, an occupation still ongoing 17 years later. That the invasion was illegal under international law cannot be seriously argued against. We now know that the decision to invade Afghanistan was made in July 2001, two months prior to the ostensible excuse of the events of 11 September 2001, themselves one of the most distorted and falsified accounts of recent history.

Nor can Australia explain why, 17 years later, it is still in Afghanistan, the Taliban government having been defeated before Christmas 2001. The official explanation, in so far as it is ever proffered, is that Australia is helping to train Afghan forces. The manifest absurdity of this claim, especially in the face of what are known to be the real reasons for the American invasion, is never questioned in the Australian mainstream media.

Acknowledging the vital role the heroin crop plays in financing off the books United States operations; control of the gas pipeline from the Caspian Sea basin; the $3 trillion worth of unexploited mineral deposits; and providing a springboard for hybrid warfare operations in Central Asia and China is not permitted in mainstream discourse.

The Afghanistan misadventure was closely followed by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, now widely regarded as one of the most disastrous United States foreign policy decisions of recent decades. Like so many of these foreign policy ventures, the 2003 Iraq invasion was built upon a multi-tiered pyramid of lies. Weapons of mass destruction are only the best known of these. The repercussions of that disastrous invasion are well documented. Three aspects from the Australian perspective are worth briefly noting.

The first is that the Howard government did not need to be asked twice to participate. To their credit, they did table in the House of Representatives the legal opinion, poor as it was, that provided the ostensible justification for joining the invasion. But even an abysmal legal argument could not conceal the absolute lack of a national interest argument as to why Australia should join an invasion of a country that posed no threat whatsoever to Australia’s national interests.

The second consequence was that the invasion spawned a plethora of terrorist groups. That these same terrorist groups are supported with arms, money, political cover and military intervention by the United States and its allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia is never acknowledged, much less discussed, in either the Australian mainstream media or in political circles.

Thirdly, the so called “terrorist attack” of 11th of September 2001 has spawned an avalanche of legislation ostensibly aimed at protecting Australia from terrorist threats, but in reality posing the greatest threat of all to human rights and civil liberties in Australia.

More than 600 pieces of legislation have been passed that directly threaten what many Australians would regard as their basic human rights. Most are unaware of the draconian nature of that legislation. Australia is the only country in the so-called democratic world that does not have a national Bill or Charter of Rights.

Significant portions of those 600+ Acts or Amendments would not survive judicial scrutiny in those democratic countries that do have a Bill of Rights or equivalent. It is difficult to know what is of more concern: that such legislation could be passed with the willing compliance of the opposition party (regardless of who is in power) or that such systematic erosion of civil liberties is not met with outrage and protest from media and public alike.

Is Australia any longer a democracy?

It is now legitimate to ask the question one never expected ever having to pose: is Australia any longer a democracy in any meaningful sense of the word?

The other military misadventure that should be noted in this context is Australia joining, yet again, a United States led “coalition” attacking Syria. This war, while Australia’s involvement from a military point of view is largely inconsequential, nonetheless reveals several aspects of Australian foreign policy.

For example, the then prime minister and foreign minister Tony Abbott and Julie Bishop respectively, announced in August 2015 that no decision would be made on joining the Syrian war until the government received legal advice on the matter. In September 2015 they announced that they were going to join that war. What they did not say was that they had received legal advice more than a year earlier. The government has refused (unlike the Howard government in 2003) to release that advice.

When asked on ABC Radio what was the legal basis for joining the war, Bishop claimed it was pursuant to a request from the Iraqi Government, and also pursuant to the collective self-defence provisions of Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.

The Iraqi Government issued a statement denying having made such a request; and Article 51 manifestly does not apply. In short, the ostensible reasons were as much a lie as the reasons given for the 2001 Afghanistan invasion and for the 2003 Iraq invasion.

The real reasons are therefore different. Based on comments made by various government ministers over time, the inference may be drawn that Australia sees involvement in unwinnable, costly and illegal wars with no discernible benefit to Australia as premium payments on the national security insurance policy, the ANZUS Treaty.

Australia helps the Americans, the argument runs, because in the event that Australia is attacked the Americans will come to their aid under the ANZUS Treaty. Like so many of the justifications put forward by the politicians for involvement in these various wars, this argument also does not withstand scrutiny.

Unlike Article 5 of the NATO treaty, the ANZUS Treaty requires the parties, effectively now only Australia and the United States, to “consult” in accordance with their constitutional procedures. Notwithstanding the vagueness of this commitment, which is far from any kind of security guarantee, it appears to be an article of faith the United States will in fact come to Australia’s aid in the event that it is ever attacked. Like most faith-based systems, it lacks any empirical basis for the belief that motivates its adherents.

That adherence to such a policy basis can result not only in involvement in wars, especially illegal ones such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, and done with no discernible national interest, it can actually operate contrary to Australia’s national interest.

Russia & China

Two recent examples are the anti-Russian campaign waged by the United States and the United Kingdom in particular, and the trade wars being waged against China by the United States, itself part of a wider anti-China policy that has essentially been a centrepiece of American foreign policy since 1949.

The anti-Russian campaign manifests itself in endless demonisation of Russia in general and of President Vladimir Putin in particular. Current illustrations of this are the alleged Russian “interference” in the 2016 US presidential election; Russia’s support for the legitimate Syrian government which is alleged to wage chemical warfare on its own people; the assault upon Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in the English city of Salisbury; and the shooting down of MH17 over Ukraine in 2014.

That there is not a shred of verifiable evidence to support any of these allegations, but rather, conclusive evidence to the contrary, is never acknowledged by the politicians, nor even given reasonable coverage by the mainstream media.

When confronted with rebuttal evidence, or even shown the manifest absurdities and contradictions of the official narrative, the standard response is either denial or, more commonly, simply ignoring the evidence. A collateral response is to attack the intellectual integrity of the person(s) making the criticism.

The hostility toward China is even less explicable. China is Australia’s largest trading partner by a very considerable margin. It is the largest source of foreign tourists, the largest source of foreign students, and the third largest source of foreign investment. Australia’s recent decades of prosperity and wealth accumulation owe more to China than to any other country. It is difficult therefore to comprehend the overt hostility, manifesting itself for example in the absurd claims about Chinese intentions in the South Pacific.

It cannot be only ignorance and prejudice that explains the constant misreporting of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, or issues in the South China Sea, Tibet, Xinjiang province and elsewhere. One possible explanation is proffered by Hugh White who suggests that Australia has never really come to terms with the unique historical phenomenon of where Australia’s largest trading partner (and source of prosperity) is not also its ally.

While this is undoubtedly true, it does not sufficiently explain the extraordinary degree of obeisance to Australia’s “joined at the hip” American ally. Even the recent revelations of obvious Russian and Chinese military superiority over the Americans have done little or nothing to shake what must now be described as blind and irrational faith.

From UK colony to American Colony

One possible explanation, and it is not suggested that it is a sufficient or complete explanation, lies in the history of 1975 outlined above and the multiple other examples of like behaviour by the Americans before and since.

That is, Australian politicians are acutely aware of the coup organised against Whitlam when he was implementing policies, past and proposed, that the Americans perceived as a threat to their vital interests. That those vital interests include waging perpetual wars for perpetual profit; attempting to maintain a unipolar hegemony over all other nations; and moving ruthlessly to invoke “regime change” upon recalcitrant nations irrespective of their designation as friend or foe, is a lesson not lost upon the Australian body politic.

Australia has gone from being a British colony to an American one without ever being truly independent. There is nothing in its current policy framework to suggest any imminent change in that position. When accompanied as it is by a progressive erosion of the structural elements of a functioning democracy, the future looks very bleak.

There is another consequence of having a foreign policy that is in effect no more than an echo of the Washington line. Australia’s region, the “near North,” is undergoing major transformation. In part this transformation is a re-assertion of the traditional dominance of the East, interrupted as it was by the Anglo-American-European imperialism of the past three centuries. That transformation is being driven by the China led Belt and Road Initiative, creating trade and political linkages not only through Eurasia, but also to South America and Africa.

The BRI in turn is linked to other major trade and security organisations such as the Shanghai Corporation Organisation and Eurasian Economic Union. There are parallel developments in the financial world leading inexorably to the demise of the Dollar based system.

The unipolar hegemonic world of the past few decades is rapidly disappearing. Australia risks isolation from the prospects offered by this new multipolar world, clinging as it does to the discredited structures of the US dominated system. Even more than a change in policy, Australia needs a change in mindset. A failure to make that adjustment to the geopolitical realities of the 21st century will inevitably lead to Australia fulfilling Lee Kuan Yew’s prophecy of becoming the white trash of Asia.

References

George Williams & Daniel Reynolds, A Charter of Rights for Australia, UNSW Press 2017

Jenny Hocking, The Dismissal Dossier: Everything you were never meant to know about November 1975, Amazon Australia, 2016

William Blum, America’s Deadliest Export, Zed Books, 2014

www.theblogmire.com (on Skripal)

Alfred McCoy, In the Shadows of the American Century, Haymarket Books, 2017

Andrei Martyanov, Losing Military Supremacy, Clarity Press, 2018

David Ray Griffin, Bush & Cheney: How They Ruined America and the World, Olive Branch Press, 2018

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.