Former CIA agent Victor Marchetti explained the U.S.-Australian relationship very well: “Australia is going to be increasingly important to the United States, and so long as Australians keep electing the right people then there’ll be a stable relationship between the two countries.” (A Secret Country, p. 353).

For 23 years before 1972, the Australian people had been electing the “right people,” the Liberal-National Country Party Coalition headed for most of that period by Robert Menzies. The Coalition was essentially conservative, and had a foreign policy which was sycophantic, to say the least. Menzies himself actually despised Australia, and would much rather have been the Prime Minister of Britain. He once said, “A sick feeling of repugnance grows in me as I near Australia.” He hated his country so much, and loved England enough to beg the British government to conduct their nuclear bomb tests from 1952 to 1958 in the Australian deserts at Maralinga (home of thirteen Aboriginal settlements). Menzies agreed to the testing without even consulting his cabinet. As John Pilger says, “Australia gained the distinction of becoming the only country in the world to have supplied uranium for nuclear bombs which its Prime Minister allowed to be dropped by a foreign power on his own people without adequate warning.” (A Secret Country, p. 168).

Later Liberal Prime Ministers turned their sycophancy towards the United States. John Gorton said in 1969 “We will go a-waltzing Matilda with you,” and Harold Holt coined the phrase “All the way with LBJ” when sending Australian troops to the Vietnam War. Again, the Liberal government was so desperate to please the Americans that they did all they could to engineer from the South Vietnamese government an invitation to send Australian troops. When the South Vietnamese government was not forthcoming, the Liberal government sent troops and advisers anyway, and mislead Parliament in a similar way that Lyndon Johnson misled Congress with the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Compared to the Coalition government (made up of the conservative Liberal and National Country parties), the Labor Party which was elected into office in December 1972 on the platform of “It’s Time” quickly showed themselves to be the “wrong people” in the eyes of the United States.

In the domestic sphere, Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s first 100 days put Bill Clinton to shame. The Whitlam government ended conscription and ordered the last Australian troops home from Vietnam. It brought in legislation giving equal pay to women, established a national health service free to all, doubled spending on education and abolished university fees, increased wages, pensions and unemployment benefits, ended censorship, reformed divorce laws and set up the Family Law Courts, funded the arts and film industry, assumed federal government responsibility for Aboriginal affairs (health, education, welfare and land rights), scrapped royal patronage, and replaced “God Save the Queen” as the national anthem with “Advance Australia Fair.”

Whitlam and several of his ministers, most notably Rex Connor, Minister for Minerals and Energy, and Dr. Jim Cairns, who eventually became Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister, wanted to pursue a policy of “buying back the farm.”

Buying Back The Farm

The 1973 oil crisis pushed the costs of energy to an all-time high, and caused disarray to economies all over the world. Australia suffered with the rest of them, with rising inflation and unemployment.

Yet one of the Whitlam government’s platforms was to reclaim Australian ownership of Australia’s vast natural resources, such as oil and minerals, and its manufacturing industries. By the late 1960s, foreign control of the mining industry, for example, stood at 60%, while 97% of the automobile industry was foreign-owned. Both Whitlam and Rex Connor had grandiose ideas for developing the necessary infrastructure, and the means to help Australian companies to “buy back the farm.” Connor’s schemes included a petroleum pipeline across Australia, uranium enrichment plants, updated port facilities, and solar energy development, as well as the establishment of government bodies with the authority to oversee development and investment in key areas, such as oil refineries and mining. Connor estimated that Australia’s mineral and energy reserves were worth $5.7 trillion dollars.

However, buying back the farm would not be cheap for a nation in the grip of inflation and economic stagnation. It was determined that the government would need about $4 billion. While Australia had an excellent credit rating with its usual lending banks in the U.S. and England, no established bank would extend Australia an amount even close to a quarter of what it wanted.

The other side to the oil crisis of 1973 was that the OPEC members in the Middle East were rolling in petrodollars. To Whitlam, Rex Connor and Jim Cairns, the Middle East seemed an appealing source of funds, as it would also be yet another step towards gaining independence from Australia’s traditional economic partners.

In 1974, Whitlam instructed Connor and Cairns to find a Middle Eastern source for a $4 billion loan.

So began the Loans affairs.

The Loans Affairs

Once word got out that the Australian government wanted to obtain such a large loan, both Connor and Cairns were inundated with offers to broker the loan. Most offers were from crackpots. There were two offers, however, which brought about the downfall of both the Ministers involved, and eventually the downfall of the Labor government.

In March 1975, Treasurer and Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns met with George Harris, a Melbourne businessman, who told Cairns that a $4 billion loan was available “with a once-only brokerage fee of 2.5%.” To confirm that the offer was genuine, Harris showed Cairns a letter from the New York office of Commerce International. According to an intermediary present at the meeting, Cairns rejected the offer, as the terms of the loan were “unbelievable” and a “fairy tale” and Cairns refused to sign any letters making a commitment to the brokerage fee. He did, however, write for Harris two letters saying that the Australian government was interested in raising a loan.

Two months later, Cairns was asked in Parliament whether he had signed a letter committing the government to a 2.5% brokerage fee. Cairns denied he had signed any such agreement. However, several days later, an incriminating letter with Cairns signature was reproduced in major newspapers around Australia. Cairns did not remember signing the letter, and said so. Nevertheless, he was forced to resign his position for misleading Parliament.

The Khemlani Affair

Minister for Minerals and Energy, Rex Connor, was also commissioned by Whitlam to find a Middle Eastern source for the $4 billion loan.

The Khemlani affair began in October 1974 when South Australian Greek emigre Gerry Karidis met up with and old friend of his, Labor Minister Clyde Cameron, at a party in Cameron’s electorate. Karidis told Cameron that he knew of some sources for loans if the Australian government was interested. Cameron passed the information on to Cairns and Connor, who then met with Karidis.

Karidis was not certain of the sources of the funds, but a friend of his said that the money could certainly be raised.

The connection between Karidis and Khemlani is circuitous. Khemlani, who was manager of Dalamal and Sons, a London-based commodities firm, was a business associate of Theo Crannendonk, a Dutch arms and commodities trader. Crannendonk in turn knew Thomas Yu, a Hong Kong arms dealer, who in turn knew Karidis’ friend, Tibor Shelley.

Khemlani said he first heard that the Australian government was interested in raising a loan while he was visiting his friend Crannendonk. Khemlani was in Crannendonk’s office when a telex about the loan came through from Thomas Yu. Khemlani volunteered to broker the loan at very reasonable rates, despite the fact that he had no experience in brokering loans, let alone such a large one.

Khemlani arrived in Australia on November 11, 1974 with Theo Crannendonk, and met with Cameron and Connor. Connor told Khemlani about the government’s interest in a $4 billion loan, and gave him a letter of introduction to that effect. On December 13, the Labor Party’s Executive Council (which on that day consisted of Connor, Cairns, Whitlam, and Lionel Murphy) authorised Connor to raise the $4 billion 20-year loan “for temporary purposes.”

The Executive Council can approve loan-raising activities without consulting the Labor Caucus or Parliament, but only if the loans are for temporary purposes. How Whitlam and his close circle of Ministers could consider a $4 billion loan over 20 years “temporary” is beyond comprehension, and smacks of attempting to keep the matter as secret as possible.

Unfortunately, by not consulting the Labor Party Caucus, Whitlam, Connor, Cairns, and Murphy were their own worst enemies. Had they consulted with their colleagues and Parliament, they would not have placed their party and their government in hot water, and would not have entertained the idea of a loan the terms of which meant that the Australian government would have to pay $20 billion in November 1995.

Various attempts were supposedly made by Khemlani to raise the money. But each time he claimed to have come up with the goods, the deals fell through. By late December of 1974, Australian Treasury and other officials became increasingly suspicious that Khemlani was leading the government on. Sir Frederick Wheeler, the permanent head of the Treasury Department convinced Cairns, then Treasurer, that Khemlani was lying to the Australian government about his ability to raise the loan.

On December 21, 1974, Connor telexed Khemlani and terminated their relationship. On January 7, 1975, the Executive Council revoked Connor’s authority to search for loan sources.

Nevertheless, Khemlani continued to work on the loan-raising, and on January 28 Connor’s loan authority was re-instated, on Khemlani’s promise that he was confident that a loan would soon be provided, even up to $8 billion. Connor’s authority, however, was reduced to securing a loan for only $2 billion.

But again Khemlani failed. For months Khemlani promised Connor he could raise the money. Connor became obsessed that Khemlani was the man to get results, regardless of the many disappointments. Khemlani let Connor down every time.

On May 20, 1975, Connor’s authority was revoked once and for all. But three days later, Khemlani contacted Connor and told him that a loan was within short reach. Connor replied positively, and continued to deal with Khemlani, behind the government’s back. Even Whitlam did not know of this. On June 10, Whitlam told a press conference that none of his Ministers any longer had the authority to raise a loan, and no loan was being raised. On July 9, Connor was asked to table in Parliament all documents relating to his loan-raising activities. He neglected to tell Parliament that he was still dealing with Khemlani.

Leaks of the loan deals appeared in various newspapers around the country. Then in October 1975, after nearly a year of promises to drum up a loan, Khemlani turned up in Australia with two suitcases full of the telexes Connor had sent him, including those sent after Connor was ordered not to contact Khemlani again. Khemlani handed the telexes over to the Opposition (who had provided Khemlani with bodyguards on his arrival to Australia), and the incriminating telexes appeared in newspapers around the country.

It is not known why Khemlani would turn on the government as he did, but it is presumed that he was handsomely rewarded for it. The Liberal-Country Party Coalition denied they had paid Khemlani, but there is evidence that the media did buy the telexes off him.

Connor was forced to resign on October 14 for misleading Parliament, just like Jim Cairns five months before him. As Whitlam had also told the Australian people that no more attempts were being made to raise such a large loan, he was also accused of misleading the public. The scandal provided for the Opposition with the “reprehensible circumstances” they needed to block the passage of the Budget though the Senate and force an election.

The scene was set for the dismissal of the Whitlam government.

Towards Dismissal

Although the Labor party won the 1972 election, it did not have a majority in the Senate. A majority is only required in the House of Representatives in order to form a government. The Senate is usually seen, and usually behaves, as a rubber-stamp body, approving the Bills introduced in the lower house. Nevertheless, in late 1973, the Coalition led by then Opposition leader, Liberal MP Billy Snedden, blocked the passage of the Budget in the Senate in order to force an election. As a result, both houses of Parliament were dissolved.

As the Labor Government was riding high in popularity, Whitlam called an election for May 1974. His government was elected for the second time in 18 months. It also gained a few more seats in the Senate. Labor and the Coalition each held 29 seats, and two independents held the balance of power.

Then in February 1975, Attorney-General Lionel Murphy was appointed to the High Court, thus leaving his New South Wales seat vacant. Traditionally, when a Minister retired from or died in office, the Premier from his State would replace him with a person from the same Party. However, the New South Wales Liberal Premier broke with tradition and appointed a non-Labor Senator. In May that year, Labor Senator Lance Barnard retired, and the Liberal Party won his seat in the June by-election. Then in June, Labor Senator Bert Milliner died in office. Queensland Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, a staunchly anti-Labor man, also broke with tradition and appointed a non-Labor man to the vacant seat. The government balance in the Senate was lost.

With three Labor seats handed to the Opposition or “independents”, it was possible for the Liberal-National Country Party Coalition in Opposition to again block Supply in the Senate. Malcolm Fraser had threatened to do since he wrested the Liberal Party leadership from Snedden in March 1975. On becoming leader of the Opposition, Fraser had announced that he would allow the government to govern, but kept his chances open to block the budget in the Senate and bring down the government, if the Labor Party provided any “reprehensible circumstances” that would force him to do so.

When the loans scandals broke, Malcolm Fraser saw his chance to bring down the Labor Government. Attempting to raise $4 billion dollars was in itself reprehensible, but for two senior Ministers (Cairns and Connor) to mislead Parliament about their activities, and for the Prime Minister to mislead the public that loan-seeking had ceased, were definitely the “reprehensible circumstances” Fraser was looking for.

Fraser made sure that he had the backing of the senior bureaucrats, big business, the legal authorities, and the media. He personally phoned the four main press barons, who ensured their support. Then on October 16, Coalition MPs in the Senate, under Fraser’s orders, deferred the Budget bills introduced by the Labor party, thus blocking Supply to the government.

Day after day in the Senate, Coalition ministers refused to pass the Budget. Without its passage, the government would run out of money and would not be able to pay civil servants’ wages or pensions. The business of government would grind to a halt and cripple the country.

The Opposition insisted that Whitlam call an election for December 1975. Whitlam refused and threatened a half-Senate election – which would cause the Senate to go to the polls – something Fraser did not want, due to the threat that Fraser could lose seats and, therefore, control of the Supply bills. Neither side would back down. The Labor government sought alternatives to the Supply budget, and designed a credit system with various banks to pay pensions and wages. As the days dragged on, public opinion began to sway in favor of the Labor Government. The public blamed the Opposition for the deadlock in the Senate, and for the government’s inability to pay wages and pensions. Many Coalition ministers began to waver, and tried to convince Fraser to back down. But Fraser stood firm in the face of public and party opinion, and risked his political career.

Meanwhile, the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr made feeble attempts to broker a peace.

Enter the Governor-General

The Governor-General is the representative of the Australian Head of State, the Queen or King of England, who is also the Queen or King of Australia. The position is one of appointment – the Governor-General is not elected by the Australian people, but is appointed by the Prime Minister of the day.

The duties of a Governor-General are ceremonial, though the there are some “reserve powers” which had never been used until November 1975.

Both John Kerr and Gough Whitlam came from working class families. Both followed careers in law, and wanted to pursue careers in politics. Both started out early in the Labor party. But while Whitlam worked his way slowly to the top, Kerr followed a different path. Even when in the Labor party, Kerr was essentially conservative, and a monarchist. As time passed, he left the Labor Party and at one time wanted to join the Liberal Party, on the condition that if he were elected, he immediately be given a seat on the front bench. Liberal party leader Robert Menzies told him he would have to wait his time like everyone else did, so Kerr abandoned the idea.

Given this background, it is interesting that Whitlam chose to appoint him Governor-General in July 1974. Kerr’s appointment was seen as an attempt to appease those who wanted a titled Governor-General as well as those who wanted someone more sympathetic to Labor. Whitlam believed that Kerr as Governor-General would take, as is the norm, “advice from his Prime Minister and from no-one else.”

But this was not the case.

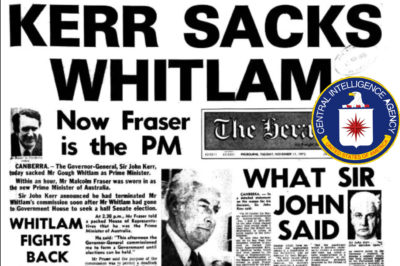

The Dismissal – November 11, 1975

The Budget crisis dragged on for a month.

On November 11, Parliament sat as usual, after the morning commemorations for Remembrance Day. Whitlam and Fraser met mid-morning, and Fraser made it clear that he would accept nothing less than a full election. Whitlam then telephoned Kerr to make a 1 p.m. appointment to speak to him about a half-Senate election. Kerr then rang Fraser and made an appointment to see Fraser 10 minutes after his meeting with Whitlam. Fraser arrived early, and to save appearances, Kerr insisted that his car be parked out of sight, so that Whitlam would not see it, and hid Fraser in a back room.

When Whitlam arrived, he was unaware that Fraser was waiting in the wings. Before Whitlam could present Kerr with the letter requesting a half-Senate election, Kerr asked the Prime Minister if he would hold a full election in December. Whitlam said no, but he would be willing to hold a half-Senate election. The Governor-General then used his reserve powers, and terminated Whitlam’s commission, at 1:10 p.m.; dismissing the government from office.

Whitlam stormed out and went to the Prime Minister’s residence, without informing his Senate ministers of what had occurred.

After Whitlam left, Kerr appointed Malcolm Fraser as caretaker Prime Minister until an election could be held on December 13.

The Senate resumed sitting after lunch, at 2 p.m. The change in government had not been publicly announced, but Fraser had informed Coalition ministers in the Senate. So when Labor Senators re-introduced the Budget Bills 75 minutes after Whitlam was dismissed, the Coalition ministers passed the Budget, thus guaranteeing their new government had Supply.

The new Coalition government called for an election on December 13, the last possible day to hold an election before the new year.

Fraser won the election.

Kerr’s Coup

Sir John Kerr always insisted that the decision to sack the Whitlam government was his alone, and that he was well within his constitutional rights and duties to do so. He also insisted that he gave Whitlam enough warning about what he might do.

Neither appears to be the case. On November 4th, Kerr consulted with the Governors of New South Wales and Victoria, and received an agreement from both that if advised by Kerr, they would not issue writs for a half-Senate election. He did this behind Whitlam’s back.

On November 6, he sought legal advice from Sir Garfield Barwick, the Chief Justice of the High Court. Barwick’s written reply was that it was the Governor-General’s duty to dismiss the Whitlam government if Kerr was satisfied that the Labor government could not secure supply. The letter further advised that Kerr should give Whitlam the options of resigning or holding a general election. If Whitlam refused to do either, then, Barwick advised, Kerr should sack him.

With Barwick’s backing, Kerr knew that dismissing Whitlam would not be considered illegal should the matter go to court.

It is worth noting that Barwick’s decision was hardly non-partisan. He is a conservative with no sympathy for the Whitlam government. Garfield was recently interviewed on ABC’s Four Corners program, during which he admitted talking with former Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies a few days before the Dismissal. There is no doubt that the former PM would have taken the news of Kerr’s decision to Fraser. This would explain why Fraser stood unwavering in his commitment to bring down the Labor government while the rest of his party were about to give up.

Kerr’s letter dismissing Whitlam said that the deadlock in the Senate had to be resolved as quickly as possible, and that Whitlam had to either resign or call a general election. He said that as Whitlam refused to do either, he was being dismissed, and a caretaker government was being appointed to secure supply and hold an election before the end of the year.

However, there are many inconsistencies between Kerr’s letter and his previous actions.

- At no stage did Kerr tell Whitlam that a prompt solution was necessary. And if a quick resolution was on his mind, why did he wait until the 26th day of the deadlock to dismiss Whitlam?

- Kerr never previously indicated that Whitlam had to either call a general election or resign. On the contrary, the opposite impression was given.

- Kerr never indicated that a half-Senate election was not suitable. Even on the 11 November, when Whitlam spoke to Kerr by phone about it, Kerr did not tell Whitlam that he would not accept it.

- Kerr said he was satisfied that there was no chance of a compromise, yet many in the Liberal party believed there would be one.

- Kerr said that a Prime Minister who could not obtain Supply could not govern, yet Supply had not yet been exhausted; the money would not run out for another two to three weeks. Why didn’t Kerr wait until Supply had run out?

- Whitlam was never given the option to resign or call a general election. Kerr simply asked him if he would hold a general election. When Whitlam said no, Kerr sacked him. Therefore, Whitlam did not refuse both his options.

- Kerr moved very secretly, and very quickly. This indicates that he did not want to give Whitlam a choice.

- Kerr appointed as caretaker Prime Minister the leader of the minority party, and stood by his decision even after the House of Representatives had passed a vote of no confidence in Fraser.

- It is also interesting to note that Kerr must have known that Fraser would accept the commission as caretaker Prime Minister, with the conditions that he would call a general election and guarantee the passage of the Supply Bills. Does that mean that he spoke to Fraser before dismissing Whitlam? If so, Fraser had prior knowledge about Kerr’s decision, and would have stood firm about blocking supply.

That may explain the comments made to the press by Deputy Liberal Party leader, Phillip Lynch just hours before the dismissal: “We believe the present course is sound for reasons which will become apparent to you later.”

After the dismissal, two other Liberal ministers said that they had known what Kerr was going to do that morning. (The Unmaking of Gough, p. 355). Of course, Fraser and Deputy Opposition leader, Doug Anthony, deny they had prior knowledge of Kerr’s decision.

These inconsistencies call into question Kerr’s motives, and lead to questions about the timing and the real reasons behind the Dismissal of an democratically elected government.

Coup D’etat – Was the CIA Involved in the Dismissal of an Australian Government?

While the Loans affairs and the Supply crisis exploded onto the front page headlines day after day, another crisis simmered in the background – the security crisis. As John Menadue, the head of the Prime Minister’s Department, says, to understand the events leading to the dismissal, you must “follow the path of the security crisis.” (The National Times, November 9-15, 1980).

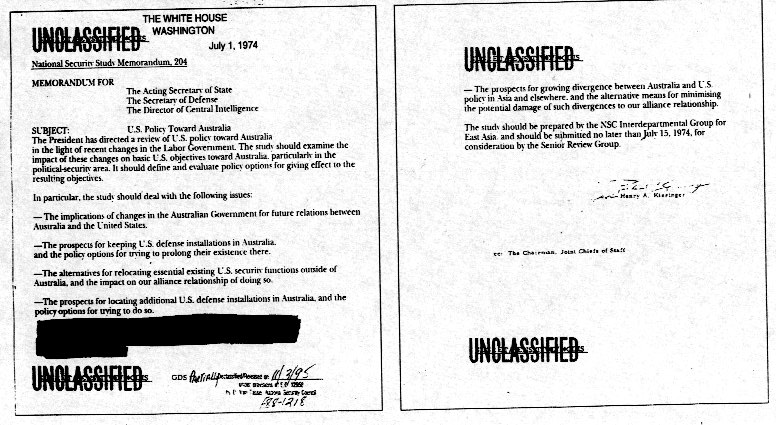

The new Labor Government’s changes in both domestic and foreign policy earned Whitlam Henry Kissinger’s epithet of “one more effete social democrat.” Neither Kissinger nor Nixon had any time for Whitlam or left-wing politicians in general.

People at the highest levels were concerned about what Whitlam might do to the long-standing Australian – U.S. relationship. CIA Director until 1975, William Colby, in his book Honorable Men, ranked the Whitlam government as one of the major crises of his career, comparable to the 1973 Yom Kippur (Arab-Israeli) War, when the U.S. had considered using nuclear weapons to help Israel win the war.

Many others in the intelligence community were concerned, including Ted Shackley, head of the East Asia Division of the CIA, who was said to be paranoid about Whitlam; and James Jesus Angleton, head of the CIA’s Counter-Intelligence section, who despised the Labor government.

One has to ask why a new government in an allied country would cause such consternation. It seems that in the areas of foreign policy and foreign (and domestic) intelligence and security that Whitlam’s Labor government stepped on a few (American) toes.

American Toes

Almost immediately after Whitlam came into office, his government’s foreign policy initiatives angered the Americans. Among Whitlam’s many sins were opening an embassy in Hanoi and allowing Cuba to open a consulate in Sydney.

The question of the Vietnam War was a particularly sticky one between the new Labor government and the Americans. Several Labor politicians had gained popularity in Australia by leading the anti-Vietnam War movement. They outspokenly called Nixon and Kissinger “mass murderers” and “maniacs” for their conduct of the Vietnam War. Dr. Jim Cairns called for public rallies to condemn U.S. bombing in North Vietnam, and also for boycotts of American products. The Australian dockers unions reacted by refusing to unload American ships. While Whitlam was more moderate than Dr. Jim Cairns, Clyde Cameron and Tom Uren (prominent anti-Vietnam War Labor Ministers), he felt he had to say something to the Americans. He wrote what he considered a “moderately worded” letter to Nixon voicing his criticism of the bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong in North Vietnam, on the basis that it would be counterproductive. Nixon, needless to say, was not amused. Some insiders said he was apoplectic with rage and resented the implications that he was immoral and had to be told his duty by an outsider. Kissinger added that Whitlam’s “uninformed comments about our Christmas bombing [of North Vietnam] had made him a particular object of Nixon’s wrath.” (Mother Jones, Feb.-Mar., 1984, p. 15)

Soon after Whitlam took office, the American ambassador to Australia, Walter Rice, was sent to meet with Whitlam in order to politely tell him to mind his own business about Vietnam. Whitlam ambushed Rice, dominated the meeting, and spoke for 45 minutes rebuking the U.S. for its conduct of the Vietnam War. Whitlam told Rice that in a press conference the next day, “It would be difficult to avoid words like ‘atrocious’ and ‘barbarous'” when asked about the bombing.

Whitlam also brought up the issue of the American bases in Australia, and warned Rice that although he did not propose to alter the arrangements regarding the U.S. bases, “to be practical and realistic,” Whitlam said, “if there were any attempt, to use familiar jargon, ‘to screw us or bounce us’ inevitably these arrangements would become a matter of contention.” (Minutes of the meeting were reproduced in The Eye, July 1987.)

Pine Gap

The issue of Pine Gap was a touchy one for the Americans.

The Pine Gap installation at Alice Springs is one of several U.S. bases in Australia. Its stated primary function is the collection of data from American satellites over the Soviet Union, China, and Europe, and other CIA sources and transmitters around the world. The base could pick up the Soviet’s coded messages about missile launchings, and can also intercept radar, radio, and microwave communications. It was integral for tracking Soviet missiles and missile testing during the Cold War, and making sure that the Soviet Union was adhering to arms control agreements. Pine Gap, as well as the other bases at Nurrungar in South Australia and North-West Cape in Western Australia are extremely important to the U.S. James Jesus Angleton, head of CIA counter-intelligence for 20 years, said Pine Gap’s importance was “unlike any similar installation that may be in any other place in the free world, it elevates Australia in terms of strategic matters.” (A Secret Country, p. 198). Among the reasons for Pine Gap’s importance are the political stability of Australia, the Australian government’s tendency towards loyalty to the United States, and the isolation of the location of Pine Gap itself. It is extremely well-placed for its purpose.

Pine Gap is supposed to be a joint facility, staffed equally by Australians and Americans. The information gathered there is also supposed to be shared. However, it had long been suspected by Australians, and by many in the Labor Party, that the Americans did not share all the information with the Australian government, nor was the U.S. forthright about some of the functions of the base.

There were at least three occasions when the Americans did not share vital information about the bases.

1) The transmitters at the North West Cape were used to assist the U.S. in mining Haiphong harbor in 1972. The Whitlam government was opposed to the mining of Vietnamese harbors, and would not have appreciated U.S. facilities on Australian soil being used to assist such an undertaking.

2) The satellites controlled by Pine Gap and Nurrungar were used to pinpoint targets for bombings in Cambodia. Again this was an activity to which the Whitlam government was opposed.

3) Whitlam was furious when he found out after the fact that U.S. bases in Australia were put on a Level 3 alert during the Yom Kippur war. The Australian bases were in danger of attack, yet the Australian Prime Minister was not alerted to this. (Incidentally, Kissinger was angered that Whitlam could be such a pest about such matters.)

There was also speculation that Pine Gap was really run by the CIA. Victor Marchetti, former Chief Executive Assistant to the Deputy Director of the CIA, and one of the drafters of the Pine Gap treaty, confirmed this suspicion: “The CIA runs it, and the CIA denies it,” he said (A Secret Country, p. 198).

It was vitally important that the American base at Pine Gap remain in Australia. The U.S. had apparently discussed re-locating the base to Guam, because of the political turmoil in Australia in 1975. The cost of relocating the base was estimated to be over a billion dollars. Besides the costs, Guam was not considered to be nearly as suitable a location as Pine Gap (The National Times, Nov. 17-22, 1975).

Whitlam’s conversation with Rice was not the only time he introduced uncertainties about the American bases. When asked in Parliament in April 1974 about Soviet approaches for scientific facilities in Australia (which were rejected), Whitlam suggested that the existing bases treaty with the Americans would not be extended.

The treaty covering Pine Gap was due for renewal in mid-December 1975.

In 1975, the Australian Defense Minister, Bill Morrison, met with CIA Director William Colby. Morrison was blunt with Colby, and said that he couldn’t guarantee the future of the U.S. bases if it was found that the CIA was involved in activities the Australian government hadn’t been told about. (The Sun, 30 April, 1977)

Yet despite such comments, it seems unlikely that Whitlam would have closed the bases down. Comments like those made to Rice and in Parliament were mostly posturing. Most comments made by Whitlam indicated that he did not mind the bases being in Australia. What he did want was to reform the alliance. He would have preferred that the U.S. keep the Australian government informed about the true functions of the bases, and disclose all information gathered by the bases – not a totally unreasonable request.

Security Risk

Nevertheless, Whitlam’s posturing caused alarm. When Ambassador Marshall Green (Walter Rice’s replacement) was interviewed years after the Dismissal, it was suggested to him that Whitlam would never have closed the bases. He answered, “You might say that with hindsight, but you don’t know how complex things were at the time. The trouble was you never really knew where you stood with him [Whitlam]” (Book of Leaks, p. 90).

Ted Shackley, chief of the East Asia Division at the CIA was furious about Whitlam’s threats to the bases. According to Frank Snepp, who served with him, Shackley was “paranoid” about Labor, and regarded it as a security risk.

After Whitlam’s threats to the U.S. bases, Shackley in return threatened to cut off the flow of intelligence information to Australia. This was a serious threat, as Australia was a long-standing member of the UKUSA agreement by which Australia, the U.S., England, Canada and New Zealand shared intelligence information with each other.

In this instance, the newly appointed CIA Station Chief in Australia, John Walker, successfully argued against cutting off the flow of intelligence information to Australia, on the grounds that the Labor government could then have legitimate grounds for shutting down Pine Gap.

The Hatchet Man

The appointment of Marshall Green as the U.S. Ambassador to Australia in 1973 indicates how seriously the U.S. took the situation. Green was far and away the most experienced man to be appointed Ambassador to Australia. The post was usually given to amateurs: friends of the President, or campaign contributors. Green, on the other hand, was a career diplomat who had served in many countries important to the U.S.

His appointment was seen by some Labor ministers as a sinister move. Senator Bill Brown called Green a “top U.S. hatchet man” and pointed out that Green’s previous postings had been marked by coups and political upheaval in four of the countries in which he had been posted, including Indonesia. He was widely known as “the coupmaster”.

Green’s stated goals (in order of importance) were 1) to maintain U.S. bases in Australia; 2) to keep the door open to American investment; and 3) to encourage Australian political support to the U.S. when and where it needed it, such as at the United Nations, and over issues such as East Timor, North Korea, and Vietnam.

Unreliable

Green’s appointment did little to ease the tensions between Australia and the U.S. government and intelligence community. It was too late.

The security crisis began when Whitlam insisted that his aides did not need to be vetted by ASIO (the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation, whose function is similar to the FBI). Sir Arthur Tange, permanent head of the Defense Department, and the UKUSA’s “main man” in Australia “dutifully” reported this to U.S. intelligence, who saw Whitlam’s move as not only irresponsible but dangerous. The next day, a U.S. Embassy official told Richard Hall, author of The Secret State, “Your Prime Minister has just cut off one of his only options.” (p. 2). Whitlam backed down immediately, but the impression of unreliability had already been made.

The Murphy Raid

The next glitch in the intelligence relationship came as a consequence of what came to be termed “the Murphy raid.” In March, 1973, the Attorney General, Lionel Murphy, was preparing security of the upcoming visit from the Yugoslav Prime Minister. It came to Murphy’s attention that ASIO was not being forthright about its knowledge of Croatian terrorist groups which might threaten the life of the Yugoslav Prime Minister. He flew down to the ASIO headquarters in Melbourne, where Commonwealth police had already secured the building, and went in search of the relevant information. The media got wind of the “raid”, and blew it out of proportion.

The CIA was furious. “We entrusted the highest secrets of counter-intelligence to Australian services and we saw the sanctity of that information being jeopardized by a bull in a China shop,” said James Jesus Angleton, head of counter-intelligence at the CIA until 1974. Angleton said the raid “had shown an outrageous lack of confidence,” and added, “how could we stand aside without having a crisis in terms of our responsibilities as to whether we would maintain relationships with the Australian intelligence services.” The threat of breaking off the intelligence relationship had been a distinct possibility (Denis Freney,The CIA’s Australian Connection, 1977, p. 27-28).

Angleton had seemed perplexed by the fact that it was Murphy’s prerogative, as an elected representative of the Australian people, and whose jurisdiction covered ASIO, to scrutinize ASIO’s activities.

ASIO, ASIS, and the CIA

As members of the UKUSA agreement, ASIO and ASIS (the Australian equivalent of the CIA) were very close to the CIA, and have often been accused of being more loyal to the U.S. and British intelligence community than to their own country’s government. In the early 1970s, many ASIO and ASIS agents were certainly ideologically closer to the right-wing elements in the CIA than to the Labor government. When Labor came to power, they did little to help the floundering relationship between the Whitlam government and the U.S., and instead tended to exaggerate the “threat” posed by the Labor party to themselves and to the American intelligence agencies.

The relationship between the Whitlam government and the intelligence services (ASIO, ASIS and the CIA) was further soured by a number of other factors. For example, members of the Labor Party complained that ASIO dedicated too much of their time to following the activities of left-wing groups, and not enough time to right-wing groups. The Croatian terrorist groups were a case in point. ASIO resented having their resources diverted to what they saw as wasteful areas, such as keeping tabs on the small Nazi party.

Another area of tension resulted when Whitlam discovered that ASIS agents were working with the CIA to destabilise Chile and overthrow President Salvador Allende. Whitlam ordered them to leave immediately. He was even more furious when he learned that the ASIS men had still not left Chile months later.

A similar fracas occurred over East Timor, during the lead-up to Indonesia’s invasion of its small neighbour. In late October 1975, Whitlam sacked ASIS head William Robertson for not informing him that there was an ASIS contact working in East Timor. This caused great consternation in the U.S., because the American government wanted the Australians to at the very least ignore Indonesia’s actions in taking over East Timor. The concern (though unfounded) was that Whitlam would side with the left-wing Timorese independence movement. Certainly many Labor ministers did favor the Fretelin movement over Indonesia.

The National Intelligence Daily, a top secret CIA briefing document for the eyes of the President, reported that “The Whitlam government seems willing to risk important relationships with Indonesia and the U.S. in order to appease leftist forces within the Labor Party.” (Book of Leaks, p.93).

Whitlam also sacked ASIO head Peter Barbour in October 1975, though the reasons are unknown. Both Robertson and Barbour were long-standing and trusted members of the UKUSA community. Both were replaced by men Whitlam thought would be more loyal to him. The replacements were not approved of by the Americans.

Whitlam also set up the Hope Royal Commission in 1975 to look into the domestic intelligence services. This was widely perceived to be a threat to the power and existence of the various intelligence organisations.

The combination of incidents involving the security and intelligence services brought a sense of disquiet to U.S. intelligence, which was reinforced by Whitlam’s occasional hints that the treaty concerning U.S. bases in Australia, including Pine Gap, may not be renewed if the U.S. did anything to anger Whitlam.

The Spy Uncovered

The security crisis reached its peak in early November 1975. In October, various Labor staff members, including those at the Prime Minister’s department, began to look into foreign intelligence involvement in Australia, including the U.S. bases.

They received a tip about Richard Stallings, the head of Pine Gap between 1966 and 1968, during the base’s construction. Whitlam heard that he was a CIA employee working under the cover of the U.S. Defense Department. In order to authenticate the information, the Prime Minister’s Department asked the Foreign Affairs Department for its list of all CIA agents in Australia. Stallings’ name was not on it. However, it came to Whitlam’s attention that the Australian Defence Department kept a more comprehensive list. Richard Stallings appeared on that list.

Sir Arthur Tange, permanent head of the Defense Department, warned Whitlam that he (Tange) had a duty to inform the CIA that Whitlam knew the identity of one of its deep cover agents. Apparently Whitlam did not object. The CIA now knew what Whitlam was up to.

In an almost campaign-style speech to an ALP rally in Alice Springs on November 2nd, 1975, Whitlam made a spur-of-the-moment remark: “Every week, he [Malcolm Fraser] gets more and more desperate in his abuse of me. I have had no association with CIA money in Australia as Mr. Anthony has,” he said, referring to National Country Party Leader, Doug Anthony, deputy leader of the Opposition. Anthony and Stallings had been friends for quite some time, after Stallings and his family had rented Anthony’s Canberra home.

Whitlam did not actually name Stallings. The next day, an article in the Australian Financial Review took up Whitlam’s accusation, and named Richard Stallings as the CIA employee, and Pine Gap as a CIA-run installation.

Anthony was compelled to defend himself. He retorted that he was not aware that his friend Stallings was a CIA man. He demanded that Whitlam provide evidence. In a speech two days later, Whitlam stated that he knew of at least two instances in which the CIA had funded the Opposition parties, but he did not provide any proof.

At this point, the Australian Foreign Affairs and Defence Departments, via the U.S. embassy in Canberra, made it clear to the U.S. State Department and President Ford that they “would welcome formal U.S. government statements denying any CIA financial involvement in Australian political parties.” (Mother Jones, p. 44). The U.S. State Department obliged, and categorically denied that Stallings was a CIA employee. The U.S. embassy and the head of the CIA, William Colby, also denied CIA involvement in Australian politics.

Sir Arthur Tange, was extremely concerned about the Stallings matter. Tange had extensive contacts with the intelligence community and realised how angry the Americans were about Whitlam and the press revealing CIA operatives and installations. He made frantic efforts to diffuse the situation. He asked Bill Morrison, the Defence Minister, to speak to Doug Anthony and convince him to drop the matter for the sake of “national security”. But it was too late. Anthony wanted to clear his name and refused to drop it. Instead, he put a question on the Parliamentary notice paper for Whitlam to provide proof of his accusations.

Whitlam’s answer was scheduled to be read on November 11, the very day Whitlam and his government would be dismissed from office in Australia’s only coup d’etat.

“National Security”

A draft copy of Whitlam’s answer was circulated, and a copy given to Sir Arthur Tange. The answer stated that Whitlam had obtained his information from the Defence Department, which in turn obtained its information from the U.S. Defence Department. Tange tried desperately to get Whitlam to modify his answer. He was concerned that because the U.S. government had categorically denied that Stallings was a CIA employee, Whitlam would be calling members of the U.S. government liars. But Whitlam refused to change his answer, as he believed that not to reveal his sources would be to mislead Parliament. On the day Whitlam was to read his answer in Parliament, Tange told a Whitlam staffer that “This is the gravest risk to the nation’s security there has ever been.” (The Nation Review, May 7-13, 1976, p.733).

The crisis inspired the now infamous cable from Ted Shackley via ASIO’s Washington office to ASIO headquarters in Australia. It is reprinted here in full:

FOLLOWING MESSAGE RECEIVED FROM ASIO LIAISON OFFICER WASHINGTON: BEGINS: ON NOVEMBER 8 SHACKLEY CHIEF EAST ASIA DIVISION CIA REQUESTED ME TO PASS THE FOLLOWING MESSAGE TO DG [DIRECTOR GENERAL].

ON 2 NOVEMBER THE PM OF AUSTRALIA MADE A STATEMENT AT ALICE SPRINGS TO THE EFFECT THAT THE CIA HAD BEEN FUNDING ANTHONY’S NATIONAL COUNTRY PARTY IN AUSTRALIA. ON 4 NOVEMBER THE U.S. EMBASSY IN AUSTRALIA APPROACHED AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT AT THE HIGHEST LEVEL AND CATEGORICALLY DENIED THAT CIA HAD GIVEN OR PASSED FUNDS TO AN ORGANISATION OR CANDIDATE FOR POLITICAL OFFICE IN AUSTRALIA AND TO THIS EFFECT WAS DELIVERED TO ROLAND AT DFA [DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS] CANBERRA ON 5 NOVEMBER. ON 6 NOVEMBER ASST SECRETARY EDWARDS OF U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT VISITING DCM [DEPUTY CHIEF OF MISSION] AT THE AUSTRALIAN EMBASSY IN WASHINGTON AND PASSED SAME MESSAGE THAT THE CIA HAD NOT FUNDED AN AUSTRALIAN POLITICAL PARTY. IT WAS REQUESTED THAT THIS MESSAGE BE SENT TO CANBERRA. AT THIS STAGE CIA WAS DEALING ONLY WITH THE STALLINGS INCIDENT AND WAS ADOPTING A NO COMMENT ATTITUDE IN THE HOPE THAT THE MATTER WOULD BE GIVEN LITTLE OR NO PUBLICITY. STALLINGS IS A RETIRED CIA EMPLOYEE [Author’s emphasis].

ON NOVEMBER 6 THE PRIME MINISTER PUBLICLY REPEATED THE ALLEGATION THAT HE KNEW OF TWO INSTANCES IN WHICH CIA MONEY HAD BEEN USED TO INFLUENCE DOMESTIC AUSTRALIAN POLITICS. SIMULTANEOUSLY PRESS COVERAGE IN AUSTRALIA WAS SUCH THAT A NUMBER OF CIA MEMBERS SERVING IN AUSTRALIA HAVE BEEN IDENTIFIED -WALKER UNDER STATE DEPARTMENT COVER AND FITZWATER AND BONIN UNDER DEFENCE COVER. NOW THAT THESE FOUR PERSONS HAVE BEEN PUBLICISED IT IS NOT POSSIBLE FOR THE CIA TO CONTINUE TO DEAL WITH THE MATTER ON A NO COMMENT BASIS. THEY NOW HAVE TO CONFER WITH THE COVER AGENCIES WHICH HAVE BEEN SAYING THAT THE PERSONS CONCERNED ARE IN FACT WHAT THEY SAY THERE ARE, E.G. DEFENCE DEPARTMENT SAYING THAT STALLINGS IS A RETIRED DEFENCE DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE.

ON NOVEMBER 7 FIFTEEN NEWSPAPER OR WIRE SERVICE REPS CALLED THE PENTAGON SEEKING INFORMATION ON THE ALLEGATIONS MADE IN AUSTRALIA. CIA IS PERPLEXED AT THIS POINT AS TO WHAT ALL THIS MEANS. DOES THIS SIGNIFY SOME CHANGE IN OUR BILATERAL INTELLIGENCE SECURITY RELATED FIELDS? CIA CANNOT SEE HOW THIS DIALOGUE WITH CONTINUED REFERENCE TO CIA CAN DO OTHER THAN BLOW THE LID OFF THOSE INSTALLATIONS WHERE THE PERSONS CONCERNED HAVE BEEN WORKING AND WHICH ARE VITAL TO BOTH OF OUR SERVICES AND COUNTRIES, PARTICULARLY THE INSTALLATIONS AT ALICE SPRINGS.

ON NOVEMBER 7, AT A PRESS CONFERENCE, COLBY WAS ASKED WHETHER THE ALLEGATIONS MADE IN AUSTRALIA WERE TRUE. HE CATEGORICALLY DENIED THEM.

CONGRESSMAN OTIS PIKE CHAIRMAN OF THE CONGRESSIONAL COMMITTEE INQUIRING INTO THE CIA, HAS BEGUN TO MAKE ENQUIRIES ON THE ISSUE AND HAS ASKED WHETHER THE CIA HAS BEEN FUNDING AUSTRALIAN POLITICAL PARTIES. THIS HAS BEEN DENIED BY THE CIA REP IN CANBERRA IN PUTTING THE CIA POSITION TO RELEVANT PERSONS THERE.

HOWEVER, CIA FEELS IT NECESSARY TO SPEAK ALSO DIRECTLY TO ASIO BECAUSE OF THE COMPLEXITY OF THE PROBLEM. HAS ASIO HQ BEEN CONTACTED OR INVOLVED? CIA CAN UNDERSTAND A STATEMENT MADE IN POLITICAL DEBATE BUT CONSTANT FURTHER UNRAVELING WORRIES THEM. IS THERE A CHANGE IN THE PRIME MINISTER’S ATTITUDE IN AUSTRALIAN POLICY IN THIS FIELD? THIS MESSAGE SHOULD BE REGARDED AS AN OFFICIAL DEMARCHE ON A SERVICE TO SERVICE LINK. IT IS A FRANK EXPLANATION OF A PROBLEM SEEKING COUNSEL ON THAT PROBLEM. CIA FEELS THAT EVERYTHING POSSIBLE HAS BEEN DONE ON A DIPLOMATIC BASIS AND NOW ON AN INTELLIGENCE LIAISON LINK THEY FEEL THAT IF THIS PROBLEM CANNOT BE SOLVED THEY DO NOT SEE HOW OUR MUTUALLY BENEFICIAL RELATIONSHIPS ARE GOING TO CONTINUE [authors’ emphasis].

THE CIA FEELS GRAVE CONCERNS AS TO WHERE THIS TYPE OF PUBLIC DISCUSSION MAY LEAD. THE DG SHOULD BE ASSURED THAT CIA DOES NOT LIGHTLY ADOPT THIS ATTITUDE. YOUR URGENT ADVICE WOULD BE APPRECIATED AS TO THE REPLY WHICH SHOULD BE MADE TO CIA.

AMBASSADOR IS FULLY INFORMED OF THIS MESSAGE.

When Shackley was interviewed years later, he said that his cable had authorisation from above. Although he did not name names, the implication was that Kissinger had given the OK. (Book of Leaks, p. 97).

The implications of the message were firstly that the CIA was bypassing the Australian government and virtually demanding that ASIO intervene and pressure the government, and that ASIO has an obligation of loyalty to the CIA to do so. The message was not meant to be passed on to Whitlam. However, the acting head of ASIO was a Whitlam appointee who saw the seriousness of the matter. He handed the cable to Whitlam. The cable was made public several years later.

The cable also made it clear that the CIA had been deceiving Australian government about Richard Stallings and Pine Gap. What else were they deceiving the Australian government about?

The cable also implied that the CIA would threaten to cut off the flow of intelligence information to the Australian services, and perhaps take even more strenuous action.

As Shackley’s cable indicated, there were several other CIA men working under cover in Australia. Their identities had not been revealed by Whitlam, but by the media. Nevertheless, there was no way for Shackley and the CIA to know how much Whitlam knew, and how much he would reveal to the public, especially about Pine Gap, but also about other CIA activities in Australia. Shackley may have already known that Whitlam had begun to look into CIA matters in Australia.

By revealing what he knew already, Whitlam had telegraphed his intentions. He had to be stopped.

Whitlam did not have the opportunity to present the proof he had about CIA involvement in Australian politics to Parliament on November 11. He was dismissed by Governor-General Sir John Kerr at 1:10 p.m. that day.

What may be nearly as unfortunate as the Dismissal of an elected government is the timing of Whitlam’s revelations about the CIA and Anthony. Labor Minister Clyde Cameron, wrote in his diaries, “Once his allegations hit the headlines, the sources dried up immediately.” (The Cameron Diaries, p. 499). Whitlam had moved too soon.

CIA in Crisis

Even in November 1975, speculation about CIA involvement in the Dismissal was rife. Since that day, speculation has not dampened.

Yet from the time allegations about Richard Stallings and Pine Gap hit the papers, the CIA and the American government denied any involvement in Australia.

This is understandable, considering that while the events of the dismissal unfolded, several Congressional committees were investigating the CIA’s activities all over the world. The CIA were facing pressures never before encountered. On November 2, 1975, the same day Whitlam made his accusations about the National Country Party being funded by the CIA, Henry Kissinger fired CIA director William Colby for being too honest with Congress. The CIA was in trouble.

If Whitlam had stood up in Parliament on November 11 and revealed that Pine Gap was a CIA-run installation and that the CIA were funding political parties in Australia, the U.S. Congress may have initiated an investigation into CIA activities in Australia. It is bad enough to undermine a third world government, but to undermine an ally is worse. The CIA would have been condemned and swiftly re-organised or worse, possibly shut down completely.

Therefore they continued to deny any involvement in the political events in Australia, and hoped the matter would fade away.

Straight from the Horse’s Mouth

Despite CIA denials, a picture has formed of their dirty tricks in Australia. And much of the evidence comes straight from the mouths of CIA employees.

Former CIA deputy director of intelligence, Ray Cline, denies that there was any “formal” CIA covert action program against the Whitlam government during Cline’s time in office (Cline left the CIA in 1973). “I’m sure we never had a political action program, although some people around the office were beginning to think we should.” He explains that the U.S. and Australia had a very healthy relationship in the area of intelligence exchange. “But when the Whitlam government came to power, there was a period or turbulence to do with Alice Springs [Pine Gap].” He went on to say, “the whole Whitlam episode was very painful. He had a very hostile attitude.”

Cline denied direct CIA interference, but outlined a scenario he saw as acceptable U.S. intelligence behavior. “You couldn’t possibly throw in a covert action program to a country like Australia, but the CIA would go so far as to provide information to people who would bring it to the surface in Australia…” for example a Whitlam error “which they were willing to pump into the system so it might be to his damage.” Such actions do not, in Cline’s opinion, amount to a “political operation.”

The method as outlined by Cline would be for the CIA to supply damaging information which the Australian security services would use against the government, presumably via other people, such as the media and the Opposition parties. This scenario fits well with what others have said. A U.S. diplomat stationed in Australia at the time, tells how CIA station chief in Australia, John Walker would “blow in the ear” of National Country Party members, and not long afterwards, the Whitlam government would be asked embarrassing questions in Parliament (The National Times, March 21-27, 1982).

Former Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns concurred that the methods used by the CIA would be as simple as that. When asked if he thought the CIA were capable of interfering with Australian politics, Cairns told the authors, “The CIA is capable, no doubt.” By interfering, Cairns means gossip, influencing people by words. He also said it was not a “conspiracy” as such, but that these people are like that anyway. That is, the CIA would seek out like-minded people: “They think the same way, act the same way – it’s not a conspiracy as such, just the way they think and act. And it’s still going on today.”

The loans affairs are perfect examples where “gossip” could have been used to good effect – and was.

Was Cairns Set-Up?

The evidence that Cairns was set up is compelling. The motives may have been not only to discredit and damage the Whitlam government, but also to get him out of the way. Cairns was already one of the most popular Labor ministers for his leadership of the anti-Vietnam war movement. His popularity rose over Christmas 1974, when as Acting Prime Minister he flew to Darwin to view the destruction caused by Hurricane Tracy. As Deputy Prime Minister, he would be the next in line to take on the leadership of the Labor Party. But as he was even more left-wing and anti-American than Whitlam, the prospect of Cairns being the next Prime Minister frightened the CIA. Even early on attempts were made to discredit Cairns. For example, ASIO leaked their dossier on him to the Bulletin (June 1974). It indicated that ASIO’s main concern about Cairn’s was the “terrorist” potential of his part in the anti-Vietnam war protests.

Far more startling are the facts concerning George Harris and the loans affair. The letter Harris showed Cairns was from Commerce International, an arms dealing company based in Belgium, and with widespread links with the CIA. Commerce International is a highly classified topic at the CIA.

It does not seem completely clear how the Opposition obtained knowledge of the letter with Cairns signature on it. However, Harris was seen with Phillip Lynch, Deputy Leader of the Liberal Party, a few days before Cairns was asked in Parliament about the letter. If Harris was legitimate, why would he leak the information to the Opposition?

Further evidence of a set-up was provided by Leslie Nagy, an intermediary at the meeting between Cairns and Harris. According to Nagy, Cairns had left the meeting, refusing to sign his name to a letter making a commitment to a brokerage fee. Yet minutes later, to Nagy’s surprise, Harris produced a letter with Cairns’ signature agreeing to the 2.5% brokerage fee. While Harris denies that he set Cairns up, Cairns still does not acknowledge that he signed the incriminating letter.

Lastly, the CIA themselves provided an interesting hint that there was some sleight-of-hand in the loans affair. The National Intelligence Daily, the CIA’s intelligence gathering arm’s top secret briefing document for the President reported on July 3, 1975 that Dr. Cairns had been sacked, “even though some of the evidence had been fabricated.” An ASIO officer writing for the Bulletin in June 1976 concurred. He said he believed that “some of the documents which helped discredit the Labor Government in the last year in office were forgeries planted by the CIA.”

Creepy Khemlani

Khemlani was a suspicious character from the word go. Why Connor chose to deal through him in the first place, and why he continued to deal with him, is a mystery.

Khemlani’s behavior during the 11 months of the loans affair was certainly peculiar. The heads of the Treasury Department and the Reserve Bank had various lengthy discussions about him. They asked the very pertinent question of why Khemlani had volunteered in the first place, and why he continued to say he could get the $4 billion loan. After all, Khemlani spent a great deal of time, and presumably a great deal of money, yet the Australian government had never promised him anything in return and had never paid him a cent. In fact, the arrangement was that Khemlani was to be paid by whomever provided the loan, rather than by the Australian government. So where was Khemlani getting his money? Why was he so patient, and why did he continue to search for the money when he was promised nothing in return?

Khemlani’s connections, and his activities after the Dismissal shed some light on the loans affair.

Khemlani heard about the Australian loan from Thomas Yu, a Hong Kong businessman. Both Yu and Khemlani’s friend Theo Crannendonk had entered into a joint venture with Commerce International’s Gerhard Whiffen, CI’s Singapore representative, in a proposal to ship arms to the CIA backed rebels in Angola. The joint venture also included Chris Brading and Don Booth. Booth was a former CIA employee. Brading was a pilot for Air America, a CIA airline which operated extensively during the Vietnam war all over South East Asia.

It is highly possible that Yu sent Khemlani to Australia to conduct dirty tricks for the CIA.

Interestingly, the CIA says it does not have any files on Khemlani. However, they told journalists Brian Toohey and Marian Wilkinson that the NSA did have information on Khemlani. The National Security Agency (NSA) is the U.S. intelligence organisation which intercepts communications overseas to pass on to other intelligence agencies. It is not surprising that they would have intelligence on Khemlani, as he was firing off telexes all over the Middle East. The NSA was very active in monitoring communications in the area, especially in the mid 1970s.

Several years after the loans affair, Khemlani was still up to his old tricks, defrauding people of their money. In 1980, Khemlani financially ruined an American businessman by the name of Charles Murphy. He left behind in Murphy’s home suitcases full of documents detailing many of his activities over the last couple of years, including his connection with the Nugan Hand Bank of Sydney.

In 1978, Khemlani entered into a relationship with the Nugan Hand Bank’s Cayman Island’s branch. The Nugan Hand Bank was based in Sydney from 1970. It collapsed in 1980 when one of its co-founders, Frank Nugan, was found dead in his car, with ex-CIA chief William Colby’s business card in his pocket. Nugan Hand Bank has since been found to have extensive links to arms and drug dealing, and the CIA. Its list of employees reads like a who’s who of the CIA and U.S. military circles. The other co-founder of Nugan Hand, Michael Hand, disappeared after the bank’s collapse. Hand was employed by the CIA for covert operations in South East Asia during the Vietnam War. Other Nugan Hand managers included General Edwin Black (Commander of U.S. forces in Thailand), Rear-Admiral Earl Yates (former Chief of Staff for Policy and Plans of the U.S. Pacific Command and a counter-insurgency specialist), Patry Loomis (CIA employee), and William Colby, head of the CIA.

It is not known if Khemlani’s ties with Nugan Hand predated their relationship in 1978. But in September of that year, he contacted them with a proposal to have Nugan Hand act as a trustee for several of Khemlani’s projects.

The papers held by Murphy also show that after his loan-raising activities with Australia, he went on to pull similar stunts in several third world countries, including Haiti, Sierra Leone, and Ghana.

In 1979, Khemlani was arrested by the FBI for stealing $1 million worth of bonds from the Citizens National Bank in Chicago. He was given a suspended 3 year sentence for turning state’s evidence and fingering the Mafia people he was working for. U.S. authorities informed ASIO of Khemlani’s arrest. Why they told ASIO is not known, as there were no Australian warrants out for his arrest.

Other evidence corroborates Khemlani’s possible CIA connections:

Former CIA employee Ralph McGehee came out with his own tell-all book on the CIA, Deadly Deceits, following the example of Victor Marchetti and Phillip Agee, who in the early 1970s released their own books about the CIA’s nefarious activities. McGehee says that the CIA played a major part in the downfall of Connor and Cairns by releasing forged documents. The documents were tabled in Parliament to discredit and damage the Whitlam government. The documents provided by Khemlani were among the forgeries.

On November 11, 1975, Whitlam received a letter, along with a draft of a telex, which shows the CIA involvement with Khemlani. The draft was found in a hotel room in Hawaii, and was posted anonymously to Whitlam. The draft reads:

DRAFT COPY ONLY

1. DO NOT TRANSMIT VIA PHONE OR LETTER. ENCIPHER BEFORE TRANSMITTING BY TELEX CONTACT ‘LM’ AT 536 6009 FOR ASSISTANCE.

REFERENCE YOUR CORRESPONDENCE ON 11 OCT, 1975.

ON 16 OCT., MR. T. KHEMLANI WILL BE DEPARTING FOR SINGAPORE TO ARRANGE MATTERS IN CASE GOVERNMENT CAPITULATION SEEMS NEAR.

IF NOT MR. KHEMLANI WILL RETURN TO AUSTRALIA ON OR ABOUT 26 OCT 75 TO CREATE FURTHER CHAOS.

NEWSPAPERS’ EDITORIALS MUST CONTINUE TO PUT PRESSURE ON THE LABOR GOVERNMENT IF CAPITULATION IS TO SUCCEED.

IF NECESSARY OFFER….

IF CAPITULATION DOES NOT SUCCEED BY 14 NOVEMBER 75, SUPPORT FROM OVERSEAS WILL CEASE UNTIL MID 76. (Author’s emphasis).

The draft telex appeared in the Sun newspaper in May 1977. The reporter said that the CIA denied they had anyone with the initials ‘LM’ working in Hawaii.

But when a National Times newspaper reporter rang the number given in the draft, they were connected to CIA headquarters in Hawaii.

Was Nugan Hand Involved?

In 1981, a CIA contract employee, Joseph Flynn, claimed that he had been paid to forge some documents relating to the loans affair, and also to bug Whitlam’s hotel room. The person who paid him was Michael Hand, co-founder of the Nugan Hand Bank. (The National Times, Jan. 4-10, 1981).

The Boyce Trial

In 1977, more confirmation and details about the CIA’s involvement in Australian politics emerged when Christopher Boyce and Andrew Dalton Lee were arrested in the United States for selling secrets to the Soviet Union.

Boyce started work in 1974 with TRW Incorporated, a Californian aerospace company which did contract work for the CIA. Boyce’s job was as a cipher clerk in the “black vault”, a code room where top-secret messages from American bases and satellites were received and deciphered. Among the bases sending messages via TRW was Pine Gap.

Boyce and Lee were both disillusioned by the state of America. One day, whilst discussing the Watergate scandal and the CIA inspired coup in Chile, Boyce said to Lee, “You think that’s bad? You should hear what the CIA is doing to the Australians.” He then told Lee about the deceptions practiced by the U.S. on the Australian government.

Boyce and Lee decided that the best way to change things was to sell the secrets Boyce learned in the black vault to the Soviets. Boyce would photograph documents, and Lee sold them to the Soviet embassy in Mexico City. While Boyce’s motivation was his idealism, Lee, a drug-addict, was in it for the money.

They were caught in 1977. Lee was arrested for loitering outside the Soviet embassy in Mexico City, and was brought back to the United States to face trial.

At his trial, part of Boyce’s defence was that he was opposed to American and CIA activities overseas, particularly in Australia. Boyce told of his initial briefing at TRW, when he was informed that most of the communication received in the black vault came from Pine Gap, and that despite an agreement between the U.S. and Australian governments to share the information obtained at Pine Gap, the U.S. was not honoring the agreement. “Certain information” was being withheld from Australia.

Boyce also told that Pine Gap was being used to monitor international telephone calls and telexes to and from Australia, especially those of a political and business nature. In addition, he said he had come across cables from the Canberra bureau chief to Langley inferring that the CIA had worked to subvert Australian unions, especially in the transport industry, and had funded the Opposition parties during Whitlam’s term. The CIA had been very concerned about an airport strike which would have delayed transportation of new equipment to Pine Gap. According to Boyce, the cable he saw said “don’t worry about that, send the stuff, we’ll take care of the strike the way we always do.” (Sunday Press, 23 May, 1982). He also told reporter William Pinwill that the CIA had a deep distrust for the Whitlam government, and had a great interest in the “monetary crisis” of 1975.

The fact that communications between Pine Gap and the U.S. were handled by a private company was also news to Australia (The Sun, 27 May, 1977).

Boyce’s lawyers had wanted to introduce evidence supporting Boyce’s claims about CIA activity in Australia. However, the judge complied with a CIA request not to allow it, because of concerns about revealing secret government information.

Both Lee and Boyce were found guilty of selling secrets to the Soviets. Lee was immediately given a life sentence. However, Boyce was sent for 90 days of psychiatric evaluation, which indicated that he might get a light sentence, probably if he kept quiet about the allegations concerning Australia. Boyce made it clear he was “outraged” about the treatment of Australia, and was subsequently given a 40 year sentence. He is kept in solitary confinement.

In 1980, Boyce escaped from prison, and led the Federal Marshalls on an 18-month chase before he was caught again. The total sentence he now has to serve is 68 years. The circumstances surrounding his escape are very suspicious.

Others Speak:

RICHARD STALLINGS

Despite repeated denials that Stallings was a CIA employee, Ted Shackley admitted Stallings’ affiliations in his cable to ASIO on the 8th of November, 1975.

Stallings went into early retirement in 1975 after suffering an injury in a car crash.

However, during his tenure as head of Pine Gap, Stallings complained bitterly about CIA activities in Australia. According to Victor Marchetti, who knew Stallings well, Stallings was “copping a lot of static from the clandestine guys operating out of Canberra. Stallings didn’t approve of the stuff at the time; he figured his information-gathering operation at Pine Gap was being put at risk by the station chief’s men, who were interfering in Australia’s political parties and labor unions.” (Mother Jones, p. 20)

JAMES JESUS ANGLETON

In June 1977, during the furore caused by the Boyce trial, Angleton was interviewed on ABC radio’s Broadband program, after complaints from ABC’s top brass that the ABC had run too many programs slamming the CIA. For “balance”, they asked Angleton to come on and give the Agency’s point-of-view. Angleton had “retired” in 1974, but had devoted several years to attempting to restore the CIA’s battered image. Angleton discussed many aspects of the “security crisis” which was the Whitlam government (in his opinion), including Murphy’s raid on ASIO, Pine Gap, and whether the CIA funded political parties in Australia. When asked “If there was any funding by the CIA in Australian politics or unions, would it have had to come through your office in the time that you were there?” Angleton answered somewhat cryptically, “I will put it this way very bluntly – no one in the agency would ever believe that I would subscribe to any activity that was not co-ordinated with the chief of the Australian internal security.” (Freney, The CIA’s Australian Connection, p. 29) . He did not deny CIA funding, nor would he clarify his statement. He simply inferred that if the CIA were involved in Australian politics and unions, ASIO would know about it.

VICTOR MARCHETTI

In an interview with the Sydney Sun, the former CIA agent related what Richard Stallings had told him. He said that Stallings had told him that the CIA station chief in Canberra had channeled money directly to the conservative political parties (Liberals and the National Country Party). Marchetti said that money was used to undermine the Labor Party, since at least 1967. He also said that there were about six to eight “upfront” CIA agents in Canberra, and up to 30 clandestine operatives throughout Australia.

ANONYMOUS SOURCE

Robert Lindsay, who wrote two books about the Boyce trial, interviewed a CIA agent who wished to remain anonymous. The agent confirmed Boyce’s allegations, but said that the CIA involvement in Australia was more complicated than Boyce realised. The agent said that CIA money was given to the Coalition and would probably have been sent through ASIO (Flight of the Falcon).

Whitlam’s Evidence

When the authors contacted former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, he politely declined to answer questions regarding CIA involvement in Australian politics. He did however, suggest that we read what he had said and written in the past.

While Whitlam was not able on November 11, 1975, to give his evidence to Parliament regarding the CIA and Richard Stallings, he did raise the matter in Parliament on May 4, 1977, because of the allegations of CIA activity brought up by the Boyce trial and by Victor Marchetti, a former CIA employee. Whitlam began by saying, “There is increasing and profoundly disturbing evidence that foreign espionage and intelligence activities are being practiced in Australia on a wide scale.”

He went to speak about the Boyce trial, and said that he had suggested to Prime Minister Fraser that he bring the matter to the attention to Justice Hope (who was still conducting the Hope Royal Commission into intelligence organisations in Australia).

Whitlam then spoke about the cable sent to ASIO headquarters by Ted Shackley. He commented that “In plain terms, the cable revealed that the CIA had deceived the Australian Government and was still seeking to continue its deception. It confirmed that Mr. Stallings had been employed by the CIA. The cable made it clear that the CIA was making what was described, in the jargon of the trade, as an ‘official demarche on a service to service link’ – in other words, without informing the elected Government of Australia. Implicit in the CIA’s approach to ASIO for information on events in Australia was an understanding that the Australian organisation had obligations of loyalty to the CIA itself before its obligations to the Australian Government. The tone and content of the CIA message were offensive; its implications were sinister. Here was a foreign intelligence service telling Australia’s domestic security service to keep information from the Australian Government.”

Whitlam also read out the statement he had prepared in response to Doug Anthony’s question on notice for 11 November, 1975: “I did not disclose that Mr. Stallings was a CIA agent. The Right Honorable gentleman [Anthony] did that. I was informed that Mr. Stallings worked for the CIA, not by the head of the Australian Foreign Affairs Department, or the United States State Department, but by the head of another of our Departments which in turn was informed by a Department in the United States other than the State Department.”

Whitlam then said, “The coup on 11 November prevented that answer being given.” (Hansard, May 4, 1977)

Whitlam also briefly discusses (for less than two pages) CIA involvement in the “security crisis” in his book, The Whitlam Government, 1972-1975. He comments that the newspaper stories disclosing the identity of Stallings and other CIA agents “greatly agitated” both Australian and U.S. security services. “The CIA sent a cable to ASIO which must have been founded on the assumption that ASIO would put its links with the CIA ahead of its obligations to the Australian Government.” He went on to say, “The episode lent colour to allegations that the CIA had been eavesdropping on me and my Ministers and had influenced the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, to sack us.”

However, Whitlam seems unwilling to say more than that. As he said in Parliament in 1977, “The difficulty which any head of government faces in responding to these matters – or any former head of government…is that he is bound by obligations of secrecy in the national interest. He cannot disclose what he knows. I readily acknowledge my own obligation.” (Hansard, 4 May, 1977, p. 1522). He will not reveal the confidences given to him by, or information about, the American installations in Australia.

While Whitlam seems to accept that at the very least Australia should investigate whether the CIA has interfered with Australian politics, he is not so sure of Sir John Kerr’s role in relation to the security crisis.

In The Whitlam Government, he says, “It is a fact that any country with the technical resources of the U.S. can eavesdrop on anyone in the world if it feels the effort worthwhile….It is not a fact, however, that Kerr, fascinated as he had long been with intelligence matters, needed any encouragement from the CIA.” (pp. 51-52)

“Our Man Kerr”

Among Christopher Boyce’s allegations is that the CIA chief at TRW had referred to Australia’s Governor-General as “Our man Kerr.”

One of the most contentious questions about the dismissal was whether Kerr acted on his own in dismissing Whitlam, or whether he was working to further someone else’s goals. The question has come up in relation to the Liberal-National Party Coalition, and to the CIA and the intelligence community.

Kerr consulted with High Court Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick before making the decision about the Senate deadlock. Garfield was a former Liberal minister. Perhaps more serious than that are the allegations that Kerr was informed of the CIA and the intelligence community’s concerns about Whitlam.

Kerr had a long association with the intelligence community, particularly military intelligence. During World War Two, he worked for the Directorate of Research and Civil Affairs, part of military intelligence. Whilst in Washington, he was seconded to the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS, precursor to the CIA). Kerr continued to work in intelligence after the war in the School of Civil Affairs (later renamed the School of Pacific Administration).

Later he became involved with the Association for Cultural Freedom, which is said to be closely affiliated with the activities of the CIA and U.S. State Department. He was also the founding president of the Law Association for Asia and the Western Pacific (LawAsia). Kerr went to the U.S. to obtain funds for LawAsia from the Asia Foundation. The Asia Foundation was discovered in 1967 to be backed by the CIA. According to CIA man Victor Marchetti, the Asia Foundation “often served as a cover for clandestine operations [and] its main purpose was to promote the spread of ideas which were anti-communist and pro-American.” (CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, p. 178-79) Despite this (or because of it?), Kerr again went to the Asia Foundation to obtain funds for LawAsia.

It is not known if Whitlam was aware of Kerr’s association with the intelligence community when he appointed him Governor-General. As Governor-General, Kerr was said to take an unusual interest in foreign policy and intelligence matters.