From New Dawn 163 (Jul-Aug 2017)

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

– George Santayana1

In May 2017, The Atlantic headlined “The Scramble for Post-ISIS Syria Has Officially Begun” as American-led forces are now directly attacking the Assad government and its Iranian-backed allies. What was once a proxy war has evolved into a Western dominated effort to “carve out spheres of influence”2 in Syria.

Like Iraq and Libya before it, Syria was next in line among a list of seven nations officially targeted by the American government to be taken out. The list, revealed by American General Wesley Clark in 2007, was quietly circulated at the Pentagon following the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan – and one by one, those targeted nations have been destabilised. The list ends with Iran.

While the mainstream media, year after year, reports on the events in the Middle East as happenstance conflicts exacerbated by popular rebellions and illogical fanatics bent on destroying infidels (unbelievers), the truth is far more revealing. The endless wars of our post-9/11 era have been a calculated drive to eliminate those resource-rich countries outside of Western corporate-military influence – most particularly countries within the sphere of Russian and Iranian influence.

To accomplish this goal, the West chose as its ally the very force against which most believe we are fighting – Islamist jihadists.

In 2015, the US watchdog group Judicial Watch obtained an August 2012 declassified US Department of Defense (DoD) document about the conflict in Syria. That document revealed, “The West, Gulf countries, and Turkey support the opposition” which, it noted, is comprised of “Salafist[s], the Muslim Brotherhood, and AQI [al-Qaeda in Iraq].”3

The document also revealed that Western support would create “safe havens” for the opposition to allow “the possibility of establishing a declared or undeclared Salafist principality in Eastern Syria… and this is exactly what the supporting powers to the opposition want in order to isolate the Syrian regime.”

Islamic State was exactly that principality predicted by the DoD document. Contrary to what the mainstream media and popular consensus intone, Islamic State and most jihadists are the undeclared allies of the West. This alliance, however, is not a new development. It is a courtship that spanned the entirety of the 20th century and into the 21st.

To study this alliance is truly an adventure in Wonderland – a crucial first step towards understanding how far the rabbit hole goes. Are you ready to take the red pill?

Global Terrorism and the Seduction of the Islamist Mind

The overriding reason for keeping the Middle East divided has been to ensure that no single power dominates the region’s oil resources and so that a strong combination of powers cannot challenge Western hegemony.

– Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs4

Today, we live in a post-9/11 world and it is therefore imperative, most of all, to understand this pivot point in the global narrative. It was 9/11 that brought the United States into Iraq, and it was the destruction of Iraq that gave rise to Islamic State (IS).But if we want to understand contemporary jihad, we must examine, at least briefly, the origin of political Islam, or Islamism, which finds its most extreme expression in Salafism, an ideology that seeks to emulate the traditions of the Salaaf (the “pious forefathers” or “devout ancestors”). Global jihad is built on a Salafist ideology, and those who answer the call are the latest participants in a decades-old effort to export Hanbali-style sharia law (the most orthodox form of sharia) from Saudi Arabia to the rest of the Muslim world via the establishment of a modern caliphate.

Significantly, the West has had a long relationship with this pan-Islamic movement.

The impetus to establish a 21st century caliphate can be traced to a late-19th century freemason named Sayyid Jamal al-Din al-Afghani who established himself in Egypt, the intellectual centre of the Islamic world, to rouse Muslims to “unite under the banner of one Caliph”5 and expel the British.

Al-Afghani’s ideological success brought him to the attention of British officials who, in 1885, met with him in London to discuss joining the forces of Islam with England in an alliance against Russia. Although al-Afghani was rebuffed, the idea of this alliance did not die. Following the First World War, Britain used the Islamic world to complete the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire. This Arab Revolt against their Ottoman rulers cleared the way for the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret agreement which carved up the Middle East between England and France, establishing the nations with which we are familiar today – Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Kuwait and others.

Preceding the Arab Revolt, the British had promised to pave the way for an Islamic caliphate centred in Mecca, the spiritual centre of Islam, under the rule of Hussein ibn Ali, Sharif of Mecca, regarded as a descendant of Prophet Muhammad. But after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the British did an about face and gave their support to Ibn Saud, patriarch of modern Saudi Arabia, whose forces took complete control of Arabia by 1924 and whose alliance with the Wahhabi cult – philosophical brethren of Salafists everywhere – would help solidify an authoritarian kingdom under Saudi rule. It would also be the start of an ideological arms race between extremist Sunni and extremist Shia sects. For the UK, it was a natural fit. The British, foremost among the world’s imperial powers, were masters at dividing indigenous populations, keeping them too busy fighting amongst themselves to unite against English rule.

Among England’s interests in the Middle East, oil was (and is) significant. Following WWI and Sykes-Picot, the region’s oilfields were in the hands of Western oil companies – companies that became synonymous with “British interests.” In all its new nations of the Middle East, England sponsored client rulers whose loyalties sided with British interests, at the expense of the local populations. Naturally, this fostered unrest in the Arab street, which found expression in three competing ideologies: Arab nationalism, communism and Islamism. Arab nationalism threatened to nationalise the oil industry, and thus extricate Western corporations from Middle Eastern oil fields. Communism threatened to do virtually the same. Islamism, however, would become a tool used by the West to undermine the threat of the other two – starting with the Muslim Brotherhood.6

In the 1920s, al-Afghani’s ideological successor, Hassan al-Banna, founded the Muslim Brotherhood, which “…preached strict observance of the tenets of Islam and offered a religious alternative to both the secular nationalist movements and communist parties in Egypt and the Middle East.”7 In 1942, during a meeting with Egyptian Finance Minister Amin Osman Pacha at their embassy in Cairo, Britain formally began financing and infiltrating the Muslim Brotherhood. A British embassy document stated that “‘subsidies from the Wafd [Party] to the Ikhwan el Muslimin [Muslim Brotherhood] would be discreetly paid by the [Egyptian] government and they would require some financial assistance in this matter from the [British] Embassy’. In addition, the Egyptian government ‘would introduce reliable agents into the Ikhwan to keep a close watch on activities and would let us [the British embassy] have the information obtained from such agents’.”8

While at the time it might not have seemed such a scandalous turn of events – at least not scandalous enough to keep out of the official record – the Brotherhood would go on to be, at the very least, the ideological foundation of every major Sunni militant organisation that has made headline news for the past fifty years.

While England cozied up to the Brotherhood, the Nazis looted the gold supply from all the central banks of Europe and laundered it by the ton through the Swiss banks.9 Following WWII, flush from the greatest robbery of the 20th century, the financial capitalists turned to America, methodically constructing the world’s most formidable war machine.

The war machine needed oil. Therefore, in 1945, just after the Yalta Conference, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Saudi Arabia’s King Abdulaziz ibn Saud aboard the USS Quincy to secure a formal arrangement that still exists today. In exchange for a steady supply of Saudi oil, the US would guarantee military support in defence of the royal family – from both internal and external threats.

One can only guess if FDR knew he was also guaranteeing support for the Saud family’s partners in authoritarian rule – the Wahhabis, the cult that provides the Saudis the spiritual authority to maintain their rule over Mecca and Medina, the holiest shrines of Islam. We will see that while al-Afghani’s ideology formed the intellectual foundation of the modern Islamist movement, the Wahhabi cult is the totalitarian source that has indoctrinated a Salafist army.

The Muslim Brotherhood and Saudi Arabia

The Muslim Brotherhood is the origin of it all. All these other extremists emanated from them.

– Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, President of Egypt10

In the 1950s, Arabs were wise to the West’s trickery, steering many to the populist side of politics. This secular, nationalist fervour must have been felt in Saudi Arabia because by 1952 the royal family had a plan in place. In a US State Department memo entitled “Conversation with Prince Saud,” the Saudi intention to ignite a pan-Islamic movement was revealed.

In the 1952 memo, Frederick Awalt, of the US State Department’s Office of African and Near Eastern Affairs, wrote: “[Prince Saud] added that Saudi Arabia was a leader among the Arab states because of two things; the presence of the Holy Cities within the Kingdom and the enormous prestige enjoyed by the King…. Some day, he said, he was going to give more tangible form to this leadership. He said he had plans which he did not wish to discuss in detail now to spark plug a pan-Islamic movement.”11

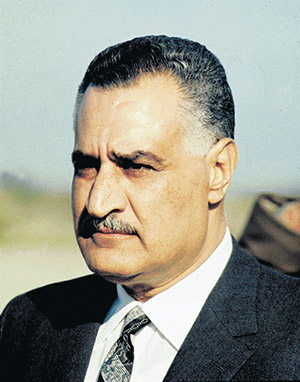

Months later, in July 1952, that prestige would be threatened by the overthrow of the Egyptian monarchy by the Free Officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser who later became President of Egypt. Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal and gained widespread support among the Arab world, inspiring a movement that became the latest, and perhaps final, expression of secular Arab Nationalism (save for the Palestinian struggle).

To the global financial powers that controlled the Suez Canal, Nasser was a threat, and with little hesitation the Muslim Brotherhood, covertly funded by Britain and infiltrated by British informants, went on the attack, attempting to assassinate him. The assassination failed. Members of the Brotherhood were rounded up, jailed, tortured, murdered and expelled.

The survivors were welcomed into Saudi Arabia. The respected Arab journalist Abdel Bari Atwan writes they were, “assimilated into the Wahhabi kingdom’s own particular brand of fundamentalism, many rising to positions of great influence. While Saudi Arabia actively prevented the formation of a home-grown branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, it encouraged and financed the movement abroad in other Arab countries.”12

By 1970, the Western powers and their client states in the Middle East had neutralised Nasser. His successor Anwar Sadat welcomed the Muslim Brotherhood back to Egypt, flush with two decades of Saudi financing and support. With Nasser’s Arab Nationalism in retreat, the plans for a Saudi inspired pan-Islamic movement, first revealed to the US in 1952, would now kick into high gear.

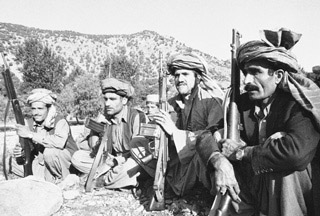

Brzezinski’s Jihad

In the 1970s, Saudi Arabia’s vaults were overflowing with oil money. The plan for a pan-Islamic movement was put into action via the funding of a Wahhabi-based madrassa (Islamic school) system dotted throughout the Muslim world – most notably in the Baluchistan province that straddles the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. By 1979, the “godfather”13 of Islamic jihad, aMuslim Brother named Abdullah Azzam, was travelling the world, proselytising the call to jihad. Azzam had studied sharia at Damascus University and Al-Azhar University in Cairo where he formed his early connections to the Muslim Brotherhood. He later took a lecturing post at the King Abdul Aziz University of Jedda, Saudi Arabia, where he is said to have become a Wahhabi. Informed by Brotherhood and Wahhabist ideology, Azzam travelled the Muslim world and inspired an army of youth into the Saudi-sponsored madrassas and CIA-funded training camps in Pakistan and Afghanistan. They came to be known as the “Afghan Arabs,” 20 to 30,000 strong, and a critical component of Afghanistan’s army of mujahideen who fought against the Soviet Union’s occupation.

Notable in this context is the name of one of Azzam’s most famous students at King Abdul Aziz University: Osama bin Laden. Azzam and bin Laden set up an office in Afghanistan to register the influx of foreign recruits, the Office of Services to the Mujahideen. This organisation would later become al Qaeda.

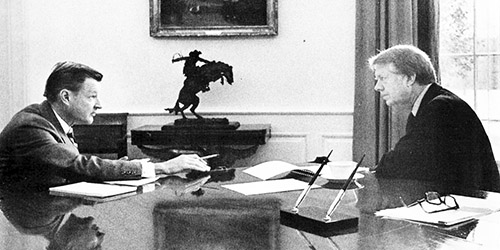

United States political strategist Zbigniew Brzezinski was President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor at the time. Years after the events in question, he revealed in an interview to Le Nouvel Observateur that the mujahideen were not roused in resistance to Soviet aggression, they were roused to incite a Soviet invasion.

“According to the official version of history, CIA aid to the Mujahiddin began during 1980, that is to say, after the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan on December 24, 1979. But the reality, closely guarded until now, is completely otherwise: Indeed, it was July 3, 1979 that President Carter signed the first directive for secret aid to the opponents of the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul. And that very day, I wrote a note to the president in which I explained to him that in my opinion this aid was going to induce a Soviet military intervention.”

Mr. Brzezinski added, “We didn’t push the Russians to intervene, but we knowingly increased the probability that they would.”14

Mr. Brzezinski referred to it as the “Afghanistan trap,” or the USSR’s Vietnam War. Conveniently, an army of youth indoctrinated through the Saudi Arabian madrassas was ready to go into action. It is now known the CIA funded the mujahideen.

The US State Department’s website, in an effort to distance itself from the idea that the United States created Osama bin Laden, quotes CNN terrorism analyst Peter Bergen: “The United States wanted to be able to deny that the CIA was funding the Afghan war, so its support was funnelled through Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence agency (ISI). ISI in turn made the decisions about which Afghan factions to arm and train, tending to favour the most Islamist and pro-Pakistan.”15 ISI’s funding went primarily to the most ruthless of mujahideen commanders, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who founded a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood in Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1960s, and was later funded by the Muslim Brotherhood during the Afghan War against the Soviets.16

The United States didn’t simply help fund the mujahideen into existence. The CIA directly provided training to those who would later be re-named terrorists and whose network would be responsible for the attacks of September 11, 2001.

Michael Springmann was former head of the American visa bureau in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia from 1987 to 1989 – the final years of the Afghan jihad. He was repeatedly ordered by “high level [US] State Department officials” to issue visas to unqualified applicants.

“I complained bitterly at the time there. I returned to the US, I complained to the State Department here, to the General Accounting Office, to the Bureau of Diplomatic Security and to the Inspector General’s office. I was met with silence. What I was protesting was, in reality, an effort to bring recruits, rounded up by Osama Bin Laden, to the US for terrorist training by the CIA. They would then be returned to Afghanistan to fight against the then-Soviets.”17

Michael Springmann was subsequently fired.

Order From Chaos

This alliance between the West and the forces of political Islam has been described by various authors as partnerships of convenience, expediency, or the result of plain ignorance. For the Western politicos involved, such assessments may very well be true. But if we step back at this point and assess the larger picture, something else begins to emerge.

By the end of the Afghan War against the Soviets, a jihad factory had been established in Pakistan. The country had transformed from an Islamic nation to an Islamist nation under the Saudi supported General Zia. The Saudi Arabian madrassa system was indoctrinating youth by the thousands into a life of jihad against what ultimately turned out to be the common enemies of the West and its client states in the Middle East. This long-term plan can be traced on paper at least back to the 1950s (as demonstrated by the US State Department memo) and, at least overtly, seems to be driven financially by Saudi Arabia, whose monarchy likely would not exist absent the support of the West. It is worth reading between the lines.

Conveniently, filmmaker George Lucas provides us with an apt analogy. In Episode II of the Star Wars saga, a young Obi Wan Kenobi arrives on Kamino to find that the Republic is in possession of a freshly minted clone army, bred in secret under orders from Supreme Chancellor Palpatine and conveniently ready to take on the impending threat of the Trade Federation’s droid forces. The Republic has no choice but to use the clone army in its defence, and the result is an all out galactic war, the Clone Wars.

To what end? In the Star Wars universe, it is the Sith who step out from the shadows and, with deceptive charm, are called to bring order to the chaos. Such is how the Empire is formed.

Global Terrorism Phase 2: Proof of Concept

…the Taliban were not a new, post-Soviet phenomenon. They were taught by the same teachers in the same seminaries that had produced the mujahideen.

– Former President of Pakistan, General Pervez Musharraf18

On 4 October 1995, Abdul Rahim Ghafoorzai, the Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs of Afghanistan, spoke at the United Nations. He was calling on the nations of the world to help end the conflict still raging within Afghanistan. By 1995, it had been six years since the mujahideen defeated the Soviets. In Afghanistan, a country nearly destroyed by war and abandoned by its former allies in the West, the people were desperate for stability.

Following the Soviet withdrawal, the United States and the Soviet Union negotiated the Geneva Accord of 1988 between Pakistan and the Republic of Afghanistan, the Soviet-backed communist regime against which the mujahideen had spent the previous decade fighting. Although the mujahideen had defeated the Soviets, they were subsequently left out of the peace process, and Afghanistan was left in the hands of Mohammad Najibullah, former head of KHAD, Afghanistan’s secret police under Soviet occupation. Not surprisingly, the mujahideen rejected the agreement. Civil war ensued. By 1992, Kabul fell to the mujahideen, and President Najibullah fled to the United Nations headquarters in Afghanistan’s capital, a refugee from a war that continued to rage after his retreat – most notably from the ongoing belligerence of Muslim Brotherhood-sponsored Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, whose support from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia allowed him to terrorise Kabul with years of rocket attacks.

Mr. Brzezinski and his ilk had achieved their primary goal – the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which officially disbanded in 1991. The next step was to extract Afghanistan from the sphere of Russian and Iranian influence. The mujahideen warlords who took control of Kabul in 1992 – those who would later be renamed the Northern Alliance – were part of that sphere.

By 1995, Hekmatyar’s belligerence had taken its toll, and the resultant instability paved the way for a brand new threat, a threat bred in Pakistan via the Saudi Arabian-backed madrassas, a threat whose very name indicated from whence they came – the Taliban. Talib means student.

When Mr. Ghafoorzai spoke at the United Nations on 4 October, the Taliban had already taken over most of the country and were knocking on the doorstep of Kabul. Mr. Ghafoorzai was amazed, in fact, that those outside Afghanistan were referring to the conflict within his country as a ‘civil war’, since not only did the funding originate from foreign sources, but the majority of fighters were foreigners, Arab youth from around the Middle East, raised in the madrassas and led to war with Pakistani logistical, technical and air support, along with additional command support from former mujahideen and enough cash to purchase a threshold of alliances. The Taliban’s initial sweep through the Pushtun provinces in 1994 possessed an air of invincibility, inevitability and the myth that the talib would stabilise Afghanistan.

“Our people find it astonishing,” Mr. Ghafoorzai said at the UN, “…[that] the actual causes of the continuing imposed war… are not understood…. Some call this a civil war in a society that they consider ‘fragmented’. Others look at it as the scene of a contest, a struggle for power. Yet others try to find the roots of the conflict in the ethnic and tribal composition of the country. The truth is far more clear: whatever it is, it is not a civil war; nor is it a tribal or ethnic conflict; it is an imposed war.”19

On 26 September 1996, the Taliban overran Kabul and stormed the United Nations headquarters. Residents awoke the next morning to find the tortured corpse of Mohammad Najibullah, the former president, hanging from a traffic tower. Two days later, the US State Department sent a cable to its embassy in Pakistan: “We wish to engage the new Taliban ‘interim government’ at an early stage to… demonstrate USG [US government] willingness to deal with them as authorities in Kabul…”20

It seems preposterous that the United States would rush to legitimise the Taliban, a barbaric regime that had primarily served to destabilise the formation of any potentially representative government. Tellingly, the oil industry along with Western governments and their allies, were painting a picture of the Taliban as a stabilising force in the region.

Central Asia is a motherlode of oil and natural gas. Afghanistan sits on the path of potential pipelines. One of the first relationships the Taliban struck was with UNOCAL, an oil company looking to construct a pipeline from the fields of Turkmenistan through Afghanistan to Pakistan.

Oil, however, was not the point. Oil is a means to an end – in this case, an attempt to normalise and legitimise the Taliban regime, for the Taliban would be the first to impose an institutional adoption of Hanbali-style sharia outside of Saudi Arabia.

Osama bin Laden

After issuing the first of two fatwas in 1998 followed by the simultaneous bombings of US embassies in Nairobi and Dar-es Salaam, Osama bin Laden became public enemy number one in the West. Global terrorism suddenly had a face, and a focus. As Abdel Bari Atwan, former editor-in-chief of the London-based pan-Arab newspaper Al Quds Al Arabi, notes in The Secret History of al Qaeda, “Al-Zawahiri’s strategy was a master stroke of propaganda; bin Laden’s face was flashed around the globe.”21

But bin Laden was neither the main theoretician of al-Qaeda, nor main strategist, nor operations chief, nor the main source of funding. Rather, he was propped up as the spiritual leader of al-Qaeda, always making clear his desire for martyrdom. He was, in a sense, the most famous would-be suicide bomber of all, giving his face and life for the cause, while a well-established network of jihad, in various stages of development for decades, operated well below the radar.

Former Muslim Brother, Ayman al-Zawahiri, has been identified as the “undisputed main theoretician and strategist of al-Qaeda.”22 Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, also a Muslim Brother, was the operations chief. And as the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks concluded in 2004:

“Contrary to common belief, Bin Laden did not have access to any significant amounts of personal wealth (particularly after his move from Sudan to Afghanistan) and did not personally fund al-Qaeda, either through an inheritance or businesses he was said to have owned in Sudan. Rather, al-Qaeda was funded, to the tune of approximately $30 million per year, by diversions of money from Islamic charities and the use of well-placed financial facilitators who gathered money from both witting and unwitting donors, primarily in the Gulf region.”23

Bin Laden was a fundraiser. He was the Jerry Lewis of the al-Qaeda Telethon. Meanwhile al-Zawahiri, who began his career as a Muslim Brother, stood by bin Laden’s side the whole time, whispering in his ear, not unlike the role Vice President Dick Cheney played to President Bush.

Bin Laden was Azzam’s successor – Azzam who created the Afghan call to war by proselytising jihad to the madrassa youth of the Muslim world. After the Soviets left, Azzam’s vision for al-Qaeda conflicted with the vision of al-Zawahiri. Azzam wanted to liberate his homeland of Palestine from the Israelis; and he likely would have been a moderating force upon bin Laden.24 Al-Zawahiri, at least at this point, was focused on liberating Islamic countries from illegitimate governments – in particular, Egypt.25 Multiple analysts have speculated, and events played out suggest, that Azzam was removed to make way for al-Zawahiri’s more extreme style of jihad in which civilians are seen as legitimate targets.

Azzam’s murder cleared the way for bin Laden to assume the public face of terrorism. And when bin Laden returned to Afghanistan in 1996, the Saudi-sponsored madrassashad already primed a fresh set of ‘clone army’ soldiers into the Afghanistan-based terrorist training camps.

CIA Director George Tenet says that an al-Qaeda defector informed the CIA that bin Laden, “…was the head of a world-wide terrorist organisation with a board of directors that would include the likes of Ayman al-Zawahiri…”26 In any corporation, the board of directors ultimately steers the ship. CEOs are hired and fired. Osama bin Laden filled a particular role, at a particular time.

Yet, as Ahmed Rashid noted in Foreign Affairs at the end of 1999:

“…Washington’s sole response so far has been its single-minded obsession with bringing to justice the Saudi-born terrorist Usama bin Ladin – hardly a comprehensive policy for dealing with this increasingly volatile part of the world.”27

Hardly, indeed. It was a classic case of misdirection. Not only was the administration of President Bill Clinton waging a covert war on a figurehead, the brunt of American foreign policy was on a collision course with Iraq.

Go to Part Two of this article in New Dawn 164.

Footnotes

1. en.wikiquote.org/wiki/George_Santayana

2. Uri Freidman, “The Scramble for Post-ISIS Syria Has Officially Begun”, The Atlantic, 20 May 2017

3. US Department of Defense, 12 August 2012, R 050839Z, www.judicialwatch.org

4. Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs, Profile Books, 2011, 264

5. A. Albert Kudsi-Zadeh, “Afghani and Freemasonry in Egypt”, Journal of the American Oriental Society 92:1, (Jan-Mar 1972) 34

6. Richard Dreyfus, Devil’s Game, Metropolitan Books, 2005; Curtis, Secret Affairs.

7. Curtis, 22

8. British embassy, Cairo, ‘First Fortnightly Meeting with Amin Osman Pacha’, 18 May 1942, FO141/838 (cited in Secret Affairs, p. 24).

9. Jean Ziegler, The Swiss, the Gold and the Dead, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998

10. Dieter Bednarz, Klaus Brinkbäumer, “Extremists Offend the Image of God”, Spiegel Online, 9 February 2015, www.spiegel.de/international/world/islamic-state-egyptian-president-sisi-calls-for-help-in-is-fight-a-1017434.html

11. National Security Archive, Conversation with Prince Saud, nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB78/propaganda%20055.pdf

12. Abdel Bari Atwan, Islamic State: Digital Caliphate, University of California Press, 2015, 194

13. Charles Allen, God’s Terrorists, Da Capo Press, 2006, 279

14. Zbignew Brzezinski, as translated and quoted in David Gibbs, “Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion in Retrospect,” International Politics 37 (June 2000) 241

15. US Department of State, ‘Did the U.S. “Create” Osama bin Laden?’, web.archive.org/web/20050310111109/http://usinfo.state.gov/media/Archive/2005/Jan/24-318760.html

16. Alfred McCoy, Politics of Heroin, Chicago Review Press, 2003, 475; Thomas H. Johnson, “Financing Afghan Terrorism,” in Harold Trinkunas and Jeanne Giraldo, eds., Terrorism Financing and State Responses, Stanford University Press, 2007, 108

17. Michael Springman, “CBC Interview,” 3 July 2002, web.archive.org/web/20030101072456/radio.cbc.ca/programs/dispatches/audio/020116_springman.rm

18. Pervez Musharraf, In the Line of Fire: A Memoir, Free Press, 2008, 209

19. United Nations, Official Records of the General Assembly, Fiftieth Session, Plenary Meetings,19th meeting, A/50/PV.19, 4 October 1995, 7

20. US Department of State Cable, 1996STATE203322, “Dealing with the Taliban in Kabul,” September 28, 1996

21. Abdel Bari Atwan, Secret History of al Qaeda, University of California Press, 2008, 79

22. Ibid., 82

23. John Roth, Douglas Greenburg and Serena Wille, “Monograph on Terrorist Financing: Staff Report to the Commission,” National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, 2004, 4

24. Aryn Baker, “Who Killed Abdullah Azzam”, Time, 18 June 2009

25. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, 36

26. George Tenet, At the Center of the Storm, Harper Collins, 2007, 102

27. Ahmed Rashid, “The Taliban: Exporting Extremism,” Foreign Affairs, (November/December 1999), 23

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.