From New Dawn 177 (Nov-Dec 2019)

Many New Dawn readers are familiar with Andrew Collins, the British writer and researcher specialising in books that “challenge the way we perceive the past.” He is a pioneer in the study of archaeoastronomy – ‘the science of stars and stones’ – the designed correspondences between prehistoric monuments and celestial patterns. In fact, Andrew Collins has become a leading player in the continually evolving field of the origins of civilisation

A central theme of his books is that the Watchers and Nephilim of Enochian literature, as well as the biblical ‘fallen’ angels and Anunnaki of Mesopotamian mythology, are memories of an elite group that helped forge the foundations of civilisation in Anatolia and the Near East. He asserts that this same region, particularly eastern Turkey, was the site of the biblical Garden of Eden and terrestrial Paradise.

In this exclusive interview for New Dawn magazine, Andrew Collins talks about his new book, co-written with Gregory L. Little, Denisovan Origins: Hybrid Humans, Göbekli Tepe, and the Genesis of the Giants of Ancient America, and lots more.

BRETT LOTHIAN (BL): In your new book Denisovan Origins: Hybrid Humans, Göbekli Tepe, and the Genesis of the Giants of Ancient America, you quite aptly begin with the paradigm-shattering findings at Göbekli Tepe. Can you explain Göbekli Tepe and how it changes our understanding of human history?

ANDREW COLLINS (AC): Göbekli Tepe is arguably one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the twenty-first century. It is a series of stone enclosures with rings of carved T-shaped pillars facing two large monoliths standing at their centres, like twin gateways into some invisible liminal realm. Located on a mountain top in SE Turkey, Göbekli Tepe was built enclosure by enclosure between 11,600-10,000 years ago. Thereafter the site was abandoned, its inhabitants spreading out across Anatolia and the Near East, and eventually into Europe, creating what is known as the Neolithic revolution.

Göbekli Tepe’s importance is its immense sophistication and the fact that it constitutes the world’s earliest known monumental architecture. Of even greater importance is that it shows us that, even by this age, modern humans had tiered hierarchical societies able to pull off incredible feats of engineering. The question then becomes: Who built it and why?

For me, it existed as part of a response to the cataclysmic events surrounding the Younger Dryas comet impact event of approximately 10,800 BCE. Caused most likely by multiple fragments of Comet Enke entering the upper atmosphere, air blasts triggered unimaginable wildfires across the Northern Hemisphere. The ash, smoke and debris rising into the air brought about a nuclear winter that instigated a 1,200-year long mini-ice age that gripped both the American and Eurasian continents and did not end until 9600 BCE, the very time frame of the construction of Göbekli Tepe.

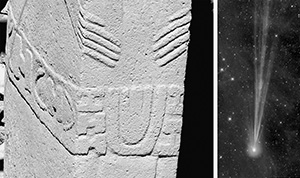

There is very clear comet imagery on one of the standing monoliths at Göbekli Tepe which tells us that its purpose was to create a place of easy access to the sky world, which was thought to lie in the northern part of the heavens. Here the supernatural creatures thought to be responsible for such cataclysms were seen to roam, their arrival in the skies marked by the appearance of comets.

These were ideas I first proposed in my 2014 book Göbekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods. I am now pretty sure they are correct as they have now been adopted by other researchers in this field, who also see the construction of Göbekli Tepe as a response to the Younger Dryas comet impact event.

BL: The enigmatic Denisovans are the most recently discovered additions to the Homo genus. Can you tell us what we know about these mysterious archaic hominids?

AC: The Denisovans were not even known about before 2010. It was in this year that a small fragment of finger bone, found two years earlier during excavations at the Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, was sequenced. It was determined the bone came from a girl of around 13 years old who lived approximately 50,000 years ago. The uniqueness of the individual’s genome made it clear she belonged to a previously unknown hominin group that would thereafter be known as the Denisovans after the place of their discovery (incidentally, ‘Denisovans’ is correctly pronounced dee-niss-o-vans and not denis-o-vans). The exact status of the Denisovans does, however, remain undecided since some scholars are convinced they are simply an early form of Homo sapiens, and not a unique human type, the reason why they have so far not been given their own species name.

What the so-called Altai Denisovan genome also made clear was that this unique human group shared more gene alleles with Neanderthals than they did with modern humans, leading to the surmise that the Denisovans must have been a sister group of the Neanderthals. This conclusion was backed up in 2016 with the discovery during excavations at the Denisova Cave of two fragments of a Denisovan skull that was particularly robust like that of Neanderthals and other early hominins. Even earlier, the discovery, again at the Denisova Cave, of two enormous molars had also suggested the Denisovans would be found to be particularly robust in nature. However, this is now known to be only part of the story, for a recent examination of the finger bone of the 13-year-old Denisovan girl who lived 50,000 years ago makes it clear that the Denisovans had long, gracile fingers like those of modern humans. This means there is every chance they looked more like us, and also perhaps thought more like modern humans that they did Neanderthals.

What is more, evidence of a sophisticated mindset existing in connection with the Denisova Cave’s Denisovan layer had already been noted. This stems from the discovery of the beautiful choritolite (chlorite) arm bangle dubbed the Denisovan bracelet, which shows evidence of sophisticated drilling, sawing and polishing, along with the earliest known bone needles used to make tailored clothing. In addition to this, fragments of a bone whistle or flute were found in the cave’s Denisovan layer, telling us that the Denisovans must have had an understanding of music, while more recently archaeologists working at the cave found an ochre “pencil” with evidence of usage. This suggests that the Denisovans were able to write and draw. The discovery of horse bone fragments and equine DNA suggested to some scholars that the Denisovans might even have domesticated and ridden horses.

All this implies that certainly by 45,000 years, and arguably earlier, the Denisovans displayed immense technological capability and advanced human behaviour. It is also now thought they developed what is known as blade tool technology, which is the product of a complicated process known as pressure flaking. This is where a handle-like instrument, usually made of bone, antler or wood, is applied to a prepared stone core to literally prise off long, slim blades or bladelets.

This blade tool technology, which started its life in southern Siberia and northern Mongolia, was then carried westwards across the Ural Mountains into Europe, as well as into southwestern Asia, where it was introduced to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of southeastern Anatolia around the same time that Göbekli Tepe came into existence. This recorded path of blade tool production suggests that the ancestors of those who built Göbekli Tepe came not just from the north, beyond the Caucasus Mountains on the Russian steppe, but from much farther east – beyond the Ural Mountains in western Siberia somewhere. It is even possible they came from as far away as the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia, where the Denisova Cave is located, or even northern Mongolia, close to the great inland sea called Lake Baikal.

Archaeologists now believe our earliest ancestors first encountered Denisovans and Denisovan-Neanderthal hybrids somewhere in northern Mongolia around 45,000 years ago. Sites in this region such as Tolbor-16 show evidence of modern human occupation, and yet they also have the same high culture associated with the Denisovan layer in southern Siberia’s Denisova Cave. This, then, is where our own slow rise to civilisation began at the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic epoch.

BL: DNA evidence reveals that ancient modern humans interbred with not only the Denisovans but the Neanderthals and as yet unidentified archaic hominids. Can you explain this complex web of interactions and how modern humans have benefitted from this gene flow?

AC: What becomes clear is that both the Denisovans and modern humans must have gained their gracile fingers from the same source, a common ancestor of both populations from whom we split around 700,000 years ago. If correct, then it means that the stubby, blunt-ended fingers displayed by Neanderthals only developed after they split from the Denisovans some 400,000 years ago (and arguably earlier still).

All this gave every branch of hominin – Denisovans, Neanderthals and modern humans – the chance to develop their own unique genome, which helped engineer their physical appearance, capabilities, and material culture. By around 45,000 years ago, the Denisovans were out in front with an acute level of human development, suggesting that as we encountered them in places like northern Mongolia, we not only interbred with them but also at the same time gained their technologies and understanding of our relationship to the cosmos. This, then, would have been the legacy passed down through their hybrid descendants to the founders of human civilisation.

After this time the Denisovans disappear from the scene, in Siberia and Mongolia at least. However, one recent genetic study suggests that some Denisovan groups might have survived in Island Southeast Asia and Melanesia through till as late as 15,000 years ago. This tells us that the sophisticated Denisovan mindset might well have been behind the spread of Australo-Melanesian ancestry from Island Southeast Asia all the way across South America, where both Australo-Melanesian and Denisovan DNA has been found among certain tribes of the Amazon.

BL: A key theme of Denisovan Origins is how cultural and technological exchange – the interaction and hybridising of archaic hominids such as the Denisovans – influenced modern humans. In your opinion, how did this flower human civilisation?

AC: What the evidence is beginning to tell us is that the Denisovans were truly sophisticated in many ways – they created beautiful jewellery, almost certainly wore tailored clothing, used musical instruments, and may even have ridden horses. On top of this, there is every possibility that they were sea voyagers, and might well have travelled between Island Southeast Asia and the Americas, South America especially. All of these technologies were thereafter passed on to their hybrid descendants, who carried them out to the farthest reaches of the Eurasian continent. Yet it is the Denisovans’ apparent invention of blade tool technology that becomes crucial in telling us exactly how far their legacy reached and which cultures benefitted from it.

The westward pulses of Denisovan technology would eventually flower among the Eastern Gravettians of central-western Russia at key sites such as Kostenki and Sungir. From these sites, as well other settlement areas in places like the Czech Republic, the Denisovan legacy was carried westward in western Europe by Proto-Solutrean groups, from whom emerged the Solutreans of southwestern Europe. Also benefitting from the Denisovans’ blade tool technology were the much later Swiderian and Post-Swiderian groups, who thrived just before, during and immediately after the Younger Dryas impact event of circa 10,800 BCE.

It is the Swiderians who I believe came to bear on the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of southeastern Anatolia, resulting in the rapid emergence of Göbekli Tepe circa 9600 BCE. You can see clear similarities between the carved art of Göbekli Tepe and that being produced around the same time by Mesolithic peoples of the Ural Mountains. The 11,600-year-old Shigir Idol best exemplifies this connection. This is a carved wooden totem pole that was found alongside other fragments of similar idols in a peat bog in the Middle Urals in 1894. It is fashioned from an enormous tree trunk and was originally around 5.3 metres in height. The style of carving, particularly of the human heads it displays, bears striking similarities to some of the carved human heads unearthed at Göbekli Tepe. It is surely no coincidence then that the same blade tool technology found at Mesolithic sites in the Ural Mountains is also found at Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites like Göbekli Tepe. There was clearly a connection between these two very distant worlds as early as 9600 BCE.

Also see The Suppression of Alternative Researchers & the Work of Andrew Collins

BL: To this day, legends such as the destruction of Atlantis, floods of astonishing proportions and of the very sky itself falling, persist all over the world about a cataclysm on a scale we can barely imagine, which you date to around 10,800 BCE. Can you explain what happened and the evidence to support this?

AC: The Younger Dryas comet impact event occurred around 10,800 BCE. It was a devastating cataclysm that ignited as much as 10 percent of the world’s biomass. However, the cosmic events just kept coming, with further fragments hitting the Northern Hemisphere periodically for around 11 years, with some estimates suggesting they continued through until around 11,340 BCE; this being at least 500 years after the initial impact event.

What we can say is that the termination of the Younger Dryas around 9600 BCE coincides almost perfectly with Plato’s proposed date for the destruction of Atlantis, and also the emergence of Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Anatolia.

BL: After the Earth-shattering events of the Younger Dryas impact, the way humans think – our social organisation and how we interact with the environment – was forever altered in many parts of the world. Can you explain these drastic changes and how they still impact us today?

AC: Understanding why Göbekli Tepe was built so soon after the Younger Dryas episode can be shown to relate to the state of mind prevailing among indigenous populations in the wake of this terrible human tragedy. Those that did survive would have feared it would happen again, and next time the world really would come to an end. Paranoia of this kind would have been widespread.

Visionary writer Barbara Hand Clow has aptly termed this fragile state of mind catastrophobia, the fear of further catastrophes. I think she is entirely right in not only predicting the existence of catastrophobia, but also in the way it would have affected generations of humanity for many thousands of years afterward.

How could you prevent catastrophobia from eating at the heart of a community every time a comet appeared in the skies? There were no psychoanalysts or counsellors back then who could offer advice on how best to overcome this problem. There were, however, go-to people who would have been considered able to allay the fear of further catastrophes. These were the complex individuals known as shamans. They can act as human interfaces between the world of the living and a perceived otherworld existing beyond the normal senses, and accessible only through dreams, visions, and the achievement of altered states of consciousness.

Shamans are able to induce trance-like states to propitiate, appease or negotiate deals with, among other things, the supernatural creatures seen as responsible for malefic intrusions into the physical world. This includes the appearance in our skies of comets, which in many ancient societies were seen as harbingers of death and destruction. Supernatural creatures of this type were generally considered animistic in form, most obviously monstrous canines (dogs), lupines (wolves), and vulpines (foxes). Comets were also associated with snakes, which in myth and legend are occasionally seen as responsible for natural catastrophes associated with impact events.

BL: Of particular interest to our more esoterically minded readers is the belief system, cosmology and spiritual practices of the “shamanic elite” that are central to your theories – the enigmatic bird shamans?

AC: From the Upper Paleolithic age through till Neolithic times, there appear to have been certain universal principles in cosmology that were reflected not only in shamanic beliefs and practices but also in ideas regarding both the origin of the soul and its destination in death. They featured the Milky Way as a kind of road or river along which the souls both of the deceased and those of shamans would take to reach an afterlife among the stars. Such beliefs were universal in both the Eurasian continent and in North America. For these beliefs to have existed simultaneously on both continents means they must be at least 12,000 years old, and arguably much older still, for it was shortly after this time that the Beringia land bridge linking the Russian Far East with North America was drowned beneath the waters of the Beringia Sea. After this time there would have been no widespread contact between the two continents.

As many as 30 to 40 Native American tribes of North America share a belief in what can only be described as the Path of Souls death journey. This involved a leap of faith at the time of death (either for the deceased or the shaman in a death trance) towards a portal located where the ecliptic, the sun’s path, crosses the Milky Way on one side of the sky. This portal was located generally in the Orion constellation, with the Messier object named M42 in the ‘sword’ of Orion being singled out for this purpose, or in the Pleiades star cluster located in the constellation of Taurus, the bull. The first appearance of the Pleiades following a period of absence each year signalled the beginning of a new year or season on both the American and Eurasian continents. It was a perfect timekeeper, and so must have become important to ancient peoples at a very early date.

From here the soul was thought to travel along the Milky Way sometimes going to the south, and even directly beneath the earth until it would eventually turn northward and reach a point where the starry stream split into two separate branches. Each branch symbolised one of two possible outcomes for the soul: one led to the afterlife, while the other led only to oblivion (or at best reincarnation). A supernatural figure standing at the fork in the Milky Way would pass judgment on the soul. It could be male or female, although most usually it was a supernatural bird or birdman, which went by the appealing name of Brain Smasher or Skull Crusher. Its purpose was, we believe, to liberate the spirit of the person trapped inside the soul in its form as a skull or head. This enabled the freed spirit to enter the afterlife proper. As Graham Hancock points out in his new book America Before, a very similar skull crushing figure stood at the same position in the soul’s journey in ancient Egyptian tradition.

These ideas are connected with the age-old belief that the seat of the soul was located in the head, the reason why the skulls of deceased peoples were revered during the prehistoric age as points of contact, not just with its former owner, but also with any ancestor associated with the person’s familial line.

Brain Smasher in Native American tradition was almost certainly identified with the Cygnus constellation, which is positioned exactly where the Milky Way splits into two separate branches. Almost universally, Cygnus is seen as a sky bird. What species it takes varies from country to country. Across most of the Eurasian continent it is usually seen as a swan or goose flying down the Milky Way. In southwestern Asia (Armenia and ancient Greece in particular) it was the vulture, while in North America it was very often a large raptor or vulture. Among the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Great Lakes-St Lawrence River region, it was a crane, goose, as well as the Thunderbird.

The one thing these birds have in common is that they were all considered soul birds – vehicles for the soul to travel from this world to the next, and then, when required, back again to the world of the living. It is most likely for this reason that bird-related paraphernalia, such as bones, skulls, feathers and talons have been incorporated into the ritual clothes of shamans since the age of the Neanderthals.

BL: A large part of Denisovan Origins focuses on the peopling of the Americas, where you and your co-writer Gregory L. Little propose a radical re-thinking of the established paradigm. Using both archaeological and DNA evidence, you both skilfully paint an entirely new and far more interesting picture of America’s ancient past, even explaining the mysterious finds of giants that the mainstream continually ignores. Can you give us a brief outline of this radical reinterpretation?

AC: Until recently North American anthropologists, palaeogeneticists and archaeologists all perpetuated the view that the First Americans came across from the Russian Far East some 15,000 years ago. They created what are known as Pre-Clovis bi-points, which with the emergence of the Clovis culture around 13,200 years ago would evolve eventually into the highly distinguishable Clovis Point.

This view has now changed. Firstly, a large number of Pre-Clovis sites have yielded types of stone tools and projectile points that have nothing to do with the later Clovis culture. Many of these sites are in the American Southwest suggesting a point of foundation in this region and not in the American Northwest, close to the former Beringia land bridge. Secondly, there is now overwhelming evidence from various genetic studies telling us that the picture is even more complicated, with migrations across the Beringia land bridge taking place as early as 24,000 years ago, while the presence of Australo-Melanesian DNA in South American tribes suggests further migrations to South America no later than 10,000 years ago.

Palaeogeneticists and archaeologists are unwilling to accept that peoples carrying Australo-Melanesian ancestry arrived in South America directly from Island Southeast Asia and Melanesia. Instead, they propose that Australo-Melanesian peoples must have embarked on an extremely arduous coast-hopping journey all around the rim of the Pacific until they reached the Aleutian Islands off Alaska, where Australo-Melanesian DNA has also been found among the indigenous Aleuts. From here they would have travelled down the Pacific coast of North America, finally entering South America.

Such a theory can certainly explain the presence of at least some Australo-Melanesian ancestry in the Americas, although it makes far more sense to assume direct transpacific journeys as well, perhaps using the ocean currents and prevailing winds that would take a vessel from the northern coast of Sahul, the former continent embracing Papua New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania, past New Zealand and down to the Antarctic continent. From here the ocean currents would have carried a vessel toward the southern tip of South America, from where it would have been an easy journey northwards along the continent’s west coast, making landfall in what is today Chile, or along the continent’s east coast, making landfall in Argentina, Uruguay, or Brazil. Navigable rivers would then have permitted a vessel entry into the interior of South America, accounting perhaps for the presence of Australo-Melanesian ancestry among certain tribes of the Amazon. With all these journeys Denisovans or, more likely, Denisovan hybrids, would no doubt have been present, explaining the presence of Denisovan DNA in some South American tribes and populations.

Then there is the likelihood also of Solutrean peoples from southwestern Europe crossing the ice flows that spanned the entire Atlantic Ocean from northern Spain across to the area of the Chesapeake Bay on the Atlantic coast of the United States at the height of the last ice age circa 22,000-20,000 years ago. This might explain why a large number of Pre-Clovis bi-points have been found in the Chesapeake Bay area that closely resemble very similar so-called leaf points manufactured by the Solutreans of southwestern Europe between 22,000-17,000 years ago. One particular example of a Pre-Clovis projectile point found in the Chesapeake Bay area is even made of a type of stone only available in France.

The presence of Solutreans in North America is backed up by genetic evidence, particularly in the fact that a particular mutation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) found extensively among the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the Great Lakes-St Lawrence River and known as haplogroup X is found also among the indigenous peoples of southwestern Europe, this being the former territories of the Solutreans. It is not found anywhere in the eastern half of the Eurasian continent, telling us that it did not enter North America from the Russian Far East.

In the book, I show that the Proto-Solutrean ancestors of the Solutreans came originally from as far east as Siberia and Mongolia and were most likely North Asian in origin. This is important since there is every reason to suspect they were carrying at least some Denisovan ancestry, as well as haplogroup X. Such a surmise makes perfect sense of the fact that the Algonquian-speaking peoples with the highest incidence of haplogroup X, the Ojibwa and Cree, also have the highest incidence in North America of Denisovan DNA, something that surely cannot be coincidence.

Also see Invoking the Chinese Immortals on Mount Tai

BL: In Denisovan Origins, you explain how the minds of the Denisovan and the Neanderthal hominids likely worked differently to that of our own. How do you think these hominids differed from us mentally and what advantages did this give them?

AC: There is good reason to suspect that the Denisovans had a completely different mindset to that of modern humans – one that acted almost like that of someone who would today form part of the autistic spectrum. If so, then some of their number might well have displayed what is known as savant syndrome, enabling them to advance quicker than their western counterparts, the Neanderthals. This is suggested by the fact that the Denisovans are known to have possessed two genes – ADSL and CNTNAP2 – that have been linked to autism in modern human populations. Is it possible that autism, and the savant-like qualities that often accompany autism, were responsible for the rise of the shamanic civilisation at the start of the Upper Palaeolithic age? This is the theory outlined in both Denisovan Origins and my previous book The Cygnus Key.

BL: Finally, I have no doubt you are already working on your next book following the truly outstanding Denisovan Origins and the central themes that make up so much of your work. What can we expect to see from you in your next work?

AC: We shall have to wait and see! At the moment I can think of nothing more beyond promoting Denisovan Origins, something that will continue for a good few months yet! However, people can keep up with my adventures on social media and also via my website at www.andrewcollins.com.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.