From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 14 No 3 (June 2020)

Like other New Dawn readers, I had heard something about Roman road-builders, Mayan mathematicians and Babylonian astronomers. But I was subsequently surprised to discover that these and other peoples achieved levels of applied science in the deep past equal to and occasionally surpassing similar material accomplishments taken for granted today. Some important innovations first conceived during antiquity were lost when the civilisation associated with their creation collapsed and were completely forgotten, only to be independently re-invented thousands of years later by modern developers utterly unaware of their ancient precursors.

Yet more remarkably, a time very long ago, when mainstream historians and conventional archaeologists assure us that superstition and ignorance alone ruled the world, human genius attained certain levels of technology still beyond our grasp. So many, in fact, that hundreds of collected specimens fill the pages of my new book until their superfluity overflowed its printed limitations. How grateful I am, then, to New Dawn for this opportunity to share with you some of the truly extraordinary instances of Ancient High Tech that missed being included in the volume so entitled!

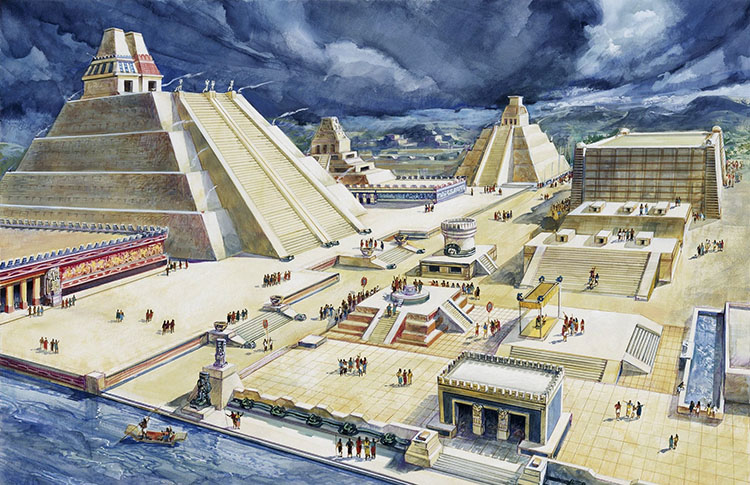

Among the most startling examples belonged to Inca medical practitioners, whose advanced healing agents were revered as part of a larger, cultural legacy inherited from Kon-Tiki-Viracocha, “Sea Foam,” pre-Columbian South America’s founding father and flood-survivor from an island kingdom of unique power, overwhelmed in prehistory by a catastrophic deluge. After establishing himself in the Andes Mountains, Inca tradition explained that he schooled their ancestors in the use of plant extracts from Digitalis lanata, a flower known today as “foxglove,” for the successful treatment of serious heart conditions. After the Conquistadors overthrew Inca Civilisation, its culture was entirely demonised, along with all traditional medical knowledge, which fell into oblivion for the next four centuries.

Not until 1930 were botanists able to extract digoxin from the leaves of the foxglove plant and discovered (re-discovered) its effective properties for treating atrial flutter and heart failure. Its resulting compound is rated today on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines as among the safest and most effective measures necessary for any health system. But teasing digoxin from Digitalis lanata demands careful precision and observant skill because the slightest error in determining the correct amount can mean the difference between strengthening the heart or inducing cardiac arrest. This life-and-death discrepancy signifies that Inca physicians not only recognised its critically narrow parameters, but themselves possessed sufficient expertise to properly act upon such a distinction.

They also applied the secrets of Matricaria chamomilla to effectively deal with gastrointestinal problems, particularly irritable bowel syndrome and intestinal cramps, when taken as a mild laxative for its anti-inflammatoryand bactericidal effects. Only within the last thirty years has research with animals demonstrated the antispasmodic, anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing), anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic (mutation reducing), and cholesterol-lowering effects of “wild chamomile,” which is additionally included in many of today’s sleep aid products. While all this is relatively new to us, the ancient Andeans were familiar with Matricaria chamomilla and its soothing benefits long before the last Inca emperor was killed in 1533. His culture likewise treated hyperlipidemia, an acquired or genetic disorder that results in high levels of lipids; these are fats, cholesterol, or triglycerides circulating in the blood.

The condition was addressed in pre-Conquest South America with extracts of plantago paralias, some forms of which additionally predispose to acute pancreatitis, and may be useful for glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. The anti-cancer effects of plantago paralias are only now being gradually appreciated. It is clear that Inca pharmaceutical and pharmacological knowledge not only far outdistanced the contemporaneous quackery of European physicians in the 16th century, but still has much to offer modern medical developments. On the other side of the Ancient World, Nile Valley practitioners similarly undertook quantum advances in the healing arts only now coming to light.

Just ten years ago, archaeologists analysing the skeletal remains of Roman Era inhabitants of Upper Egypt and adjacent Nubia during the early 1st century CE found the presence of tetracycline, an antibiotic in use today for treating bacterial infections. The Egyptians ingested tetracycline with a special beer concoction not unlike sour porridge. Further investigation revealed that retrieved Roman Era samples were identical in substance to the same beverage dating to the advent of Pharaonic Civilisation, more than three thousand years before.

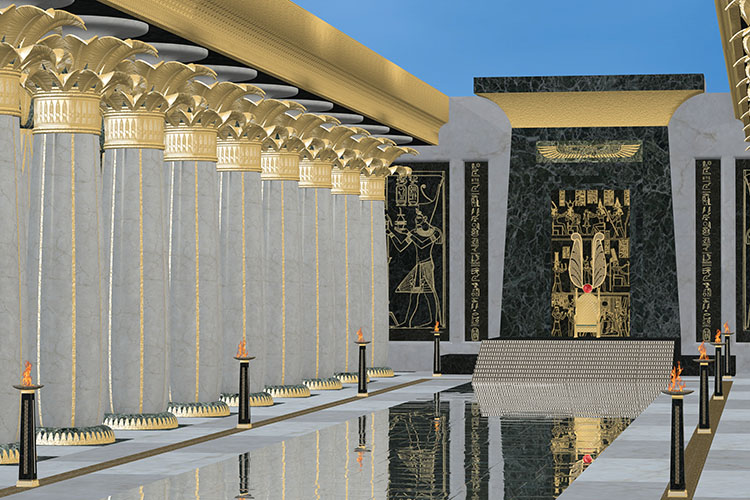

Related evidence in the form of surviving medical papyri revealed how dynastic physicians and brewers deliberately contaminated their beer with streptomyces, tetracycline-producing soil bacteria that thrives in the arid conditions of the Egyptian desert. Their grain thus laced with tetracycline, the Egyptians observed how it cured them of various bacterial ailments, five thousand years before the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, in 1928. Their high level of medical science helps explain why many residents of the Nile Valley experienced healthy longevity, such as the famous Pharaoh Ramses II, who lived to celebrate his ninety-seventh birthday.

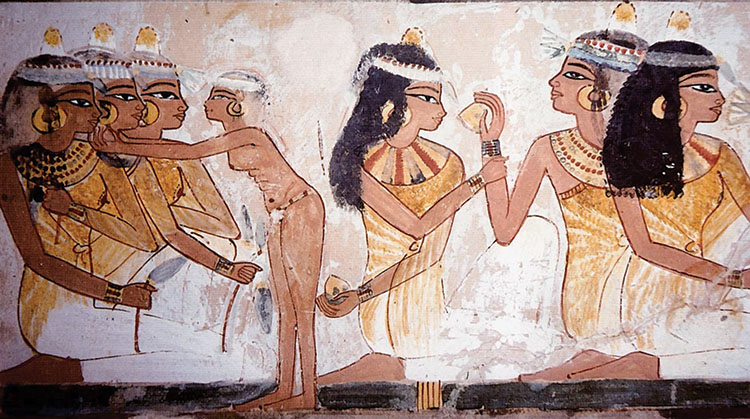

Advances in Egyptian dentistry were constantly stimulated by the country’s persistent problem of sand blown by desert winds into food consumption, a dilemma that occasioned the world’s oldest known recipe for toothpaste. The 4th century CE papyrus is a Greek-language copy of a traditional Egyptian invention already in common use at the outset of the 1st Dynasty, thirty-four hundred years earlier. The original formula calls for one drachma (one-hundredth of an ounce) of rock salt, another drachma of mint, and one more drachma of dried iris, plus twenty grains of pepper.

Dentists only recently re-discovered the beneficial properties of the iris flower, which has been found effective against gum disease and is now in commercial use again after the passage of sixteen centuries – yet another example of an ancient innovation reaching out from the deep past to influence modern technology. According to the sixteen hundred-year-old papyrus, all its specified ingredients should be crushed and mixed together into a “powder for white and perfect teeth.” It was discovered by Dr Hermann Harrauer, in charge of the papyrus collection at Vienna’s National Library, in 2002, atop a rubbish dump outside the modern Egyptian town of Al-Mahamid Qibly, the dynastic Imiotru, known to the Greeks as Crocodilopolis because it housed the most prominent Early-Middle Kingdom sanctuary (2050 BCE–1652 BCE) of the crocodile-god Sobek.

His name is a participial form of the verb sbq, “to unite,” or “create wholeness,” i.e., “health,” and therefore appropriate to the discovery of a toothpaste recipe, especially given Sobek’s abundant and powerful teeth. “It was written,” observed Dr Harrauer, “by someone who obviously had some medical knowledge as he used abbreviations for medical terms.” The ancient Nile Valley cleaning agent was faithfully replicated by an Austrian dentist, Dr Heinz Neuman. “Nobody in the dental profession,” he declared, “had any idea that such an advanced toothpaste formula of this antiquity existed.” A colleague volunteered to personally test the recreation. “I found that it was not unpleasant,” said Dr Neuman. “It was painful on my gums and made them bleed, as well, but that’s not a bad thing, and afterwards my mouth felt fresh and clean. I believe that this recipe would have been a big improvement on some of the soap toothpastes used much later.”

Anglo-American soap industrialist William Colgate began marketing the first commercial toothpaste in 1873, but it was hygienically inferior to its pharaonic forerunner, which had been lost since the Ancient Old World collapsed. Egyptian dental care even extended to the invention of breath mints made, as recounted in a 16th Dynasty papyrus, from combining cinnamon, frankincense and myrrh, boiled together into a honey base, then shaped as small pellets for easy consumption. Myrrh, a natural gum extracted from tree resin, is analgesic – a pain killer. The Ancients’ greatest contribution to general health, however, was their institution of general hygiene.

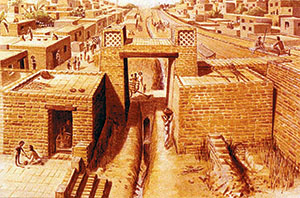

While the Roman baths are famous, they were preceded three thousand years by the lesser-known public water facilities of 4th Millennium BCE Mesopotamia and India. In describing the Indus Valley’s earliest urban centres, US researcher David Hatcher Childress writes that “the plumbing sewage system throughout the large cities is so sophisticated that it is superior to that found in many Pakistani (and other) towns today. Sewers were covered and most homes had toilets with running water. Furthermore, the water and sewage systems were kept well separated.” Near Baghdad, homes and sacred structures in the Sumerian city of Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Iraq) featured elaborate arrangements for personal sanitation.

“One excavated temple,” according to Childress, “had six toilets and five bathrooms.” He goes on to quote the July 1935 issue of Scientific American magazine, explaining that the temple’s plumbing equipment “connected to drains which discharged into a main sewer, one meter high and fifty meters long. In tracing one drain, the investigators came upon a line of earth ware pipes. One end of each section was about eight inches in diameter, while the other end was reduced to seven inches, so that the pipes could be coupled into each other, just as is done with drainpipes in the 20th century.”

Very old as Sumerian plumping may have been, its age pales compared to a series of anomalous lead pipes inadvertently discovered inside three caves at Báigōngshān, the “White Mountain,” earlier this century by palaeontologists visiting China from the United States. With an eighteen-foot-high ceiling, the largest cave features two reddish-brown pipes sixteen inches in diameter. Outside and above its entrance, dozens of hollow pipes, some likewise sixteen inches in diameter, with others down to four inches in width, protrude horizontally from the rock face. About two hundred sixty feet from the cave’s mouth, similarly hollow formations appear on the beach of and within Lake Tuosu, protruding vertically from the water or lie just below its surface, although they differ in ranging from 0.8 to 1.8 inches diameter, and have an east-west orientation. After the American palaeontologists shared their discovery with local authorities in the city of Delingha, the Báigōngshān and Lake Tuosu sites were written up in a six-part series of articles published by Henan Dahe Bao, the “Henan Great River News,” in June 2002.

These reports attracted the attention of state geologists and geophysicists, who visited and studied White Mountain, returning to the Beijing Institute of Geology with sample fragments which were subjected to standard examination procedures. These dated the objects to circa 150,000 Years Before Present. Additional testing with different chronological methods consistently repeated the same time parameter, until even stubborn disbelievers, such as Brian Dunning of Skeptoid.com, in the US, were forced to concede the pipes’ Middle Palaeolithic provenance, tens of thousands of years before homo sapiens arrived in Asia.

Interviewed by a prominent, state-run newspaper, The People’s Daily, in 2007, Zheng Jiandong, a geology research fellow from the China Earthquake Administration, half-heartedly proposed a natural explanation. He wondered if iron-rich magma may have arisen from deep within the Earth, elevating iron into fissures, where it may have solidified into tubes. He admitted his speculation was apparently negated by not only the pipes own, decidedly artificial appearance, but by their physical connection to nearby Tuosu, more convincingly suggesting a manmade function as part of some water supply system. Moreover, their non-random, uniformly east-west alignment on the lakeshore contradicts a magmatic hypothesis. Additional samples were further analysed at a local smelter, where eight per cent of their material composition could not be identified. “There is indeed something mysterious about these pipes,” Jiandong said.

There is also something mysterious about an object found in January 2019 by former Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Dr Michael Torres while sweeping his metal-detector over Melbourne Beach, on the east coast of Florida, in the United States. Brushing the concealing sand aside brought to light what appears to be an Inca “funeral mask” embossed with an anthropomorphic figure surrounded by geometric designs. Dr Torres convincingly speculates that it was part of South American riches taken by 18th century Spaniards who packed their looted treasure aboard a galleon that sank in a storm. Since then, pieces driven by wave action continue to wash up onshore.

The mask’s humanoid image is similar to other native representations of Kon-Tiki-Viracocha, the flood-hero described in our above discussion of Andean herbal medicine. What most sets the object apart from other such artefacts, however, is its construction from iridium, supposedly first discovered by London chemist Smithson Tennant in 1803. It took ten more years for another British scientist, John George Children, to melt a very small sample of iridium with the aid of the most galvanic battery available at the time. The first melting of iridium in appreciable quantity was finally accomplished by 1860 when blast furnaces had become powerful enough for the job.

Yet, the same achievement was successfully undertaken nearly three thousand years before at the hands of a nameless pre-Inca people, whose surviving copper slag heap at Wankarani, in the Bolivian highlands, is a likely site for the mask’s creation between 900 BCE and 700 BCE when artisans there were known to have been the premiere metal smiths of pre-Columbian South America.

The Melbourne Beach find comprises a copper base upon which extraordinarily high temperatures have fused an iridium surface covered with melted silver and gold. As the most corrosion-resistant material known, iridium is the second-densest metal after osmium, with which it is sometimes combined in an alloy for pen tips and compass bearings. Iridium is one of the rarest elements in Earth’s crust, with annual production and consumption of only three tons. Most of it comes from outer space, delivered to our planet’s surface in meteor, asteroids and comet collisions over the course of millions of years.

How the Wankarani could have found, let alone identify scarce iridium – much less sufficiently melt this very high density, nearly immalleable and exceptionally hard mineral for artistic workmanship – is made all the more impossible by archaeologists’ insistence that furnaces operated by pre-Spanish Bolivians never approached the extraordinarily high temperatures required to melt iridium. Indeed, that was only achieved, as history tells us, as recently as the 19th century. Yet, there is the Andean mask, material proof to the contrary, and physical evidence of a technological level unequalled for some twenty-seven hundred years.

It is haunted by even more intriguing and difficult questions to answer: What was the artefact’s purpose? Why was so challenging a metal chosen for its medium of creation? Iridium’s stellar melting point makes it among the most heat-resistant minerals known. Was the Melbourne Beach object really a “funeral mask” as some observers believe? Or was it a face plate of some kind to protect someone, very long ago, from an encounter with a dangerous heat source? Its further study may tell.

Learn more by reading Frank Joseph’s book Ancient High Tech: The Astonishing Scientific Achievements of Early Civilizations (Bear & Company), which explores the advanced technology, science, and medicine achieved by ancient civilisations hundreds and thousands of years ago.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.