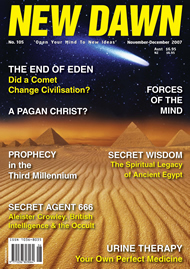

From New Dawn 105 (Nov-Dec 2007)

Strictly speaking, a pagan Christ is a contradiction in terms. The very concept of paganism was constructed by Christians who wanted to distinguish their faith from the old religion of Greece and Rome, which by the end of classical antiquity was observed only by peasants in remote rural areas – the pagani, or “country people,” or – to use words that are similar in tone – rustics, rubes, hayseeds. So there can be no pagan Christ. Paganism is all that Christianity is not.

Once we go past this elementary point, however, we see that the situation is not so simple. The resemblance between Christianity and its rivals could never be entirely overlooked. The Church Father Augustine (354–430) wrote, “That which is now called the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and never did not exist from the planting of the human race until Christ came in the flesh, at which time the true religion which already existed began to be called Christianity.” Whatever Augustine meant by this – and it’s not entirely clear from the context – one thing it could mean is that the “true religion” is universal and has always existed; only comparatively late did it come to be codified in the teachings of Christ.

Before I go further into what this “true religion” might be, it’s necessary to stop and take a look at early Christianity in its context. Christianity, as is well known, grew up in the Roman Empire, a time of remarkable fecundity in religious belief, with a huge and dizzying marketplace of gods and cults and philosophies for the seeker to choose from, many of which bore more than a passing resemblance to one another. It’s impossible to believe that Christianity was not affected by this background. Although the Christians insisted that their religion was true and all the others were false, they still had to account for the fact that theirs was not so different from many of those they were denouncing.

Over the past century, one of the most influential views of the relationship between Christianity and paganism has been that of Sir J.G. Frazer (1854–1941), author of the classic work The Golden Bough, first published in 1890 and updated in many editions thereafter. A pioneer of comparative mythology, Frazer delved into the compendious collections of lore and legend that scholars were amassing in his time and noticed that Christianity had taken many of its elements from the religions it would eventually displace.

The most famous instance is Christmas. The birthday of Christ was not recorded and is not known; in the early centuries of the religion that bears his name it was not celebrated. But by the fourth century, Christ’s birthday came to be observed as a holiday. In the East (starting in Egypt), the date selected was January 6. But the Western church, which had never observed this date, set Christ’s birthday as December 25. Why? One Christian writer quoted (but not named) by Frazer explains: “It was a custom of the heathen to celebrate on the same twenty-fifth of December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and festivities the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day and the festival of the Epiphany on the sixth of January.”

Another, possibly more revealing, case involves the festival commemorating the death and resurrection of Christ. Today Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the full moon after the March equinox. (This is to some extent a simplification of the complex process of fixing the date of Easter, but it will serve our purposes here.) Frazer noted that there was an ancient tradition by which the death of Christ was observed on March 25, regardless of the phase of the moon. Remarkably, this coincided with the date on which the death and resurrection of a pagan god, Attis, was celebrated. Still more significantly, the parts of the world where Christians observed Easter on this date – western Asia Minor and Rome – were precisely the areas where the cult of Attis was most popular.

Attis, according to the myth, was a handsome young shepherd who was born of a virgin. Beloved of the Great Goddess of life, he was said in some legends to have been killed by a boar, in others to have died after castrating himself. (The priests of the Attis cult were all self-made eunuchs, in imitation of him.) After his death, he was changed into a pine tree.

It’s curious that the death and resurrection of Christ should have been celebrated in such close conjunction with that of one of the deities that the Christians so detested. What’s even more interesting is the underlying similarity of the myths: both are celebrations of a god, born of a virgin, who has died and risen again. More surprisingly still, Attis was not the only god in antiquity who was believed to have died and risen again. There was also Adonis, worshipped in Babylonia and Syria. Adonis, another beautiful young man, was said to die every year. His death caused passion to cease and beasts and men to forget to reproduce; all life would be extinguished if Ishtar, the goddess of life, did not rescue him annually from the halls of death. And of course there is Osiris, the slain and dismembered king of Egypt who was reassembled by his wife Isis (another goddess of life) to serve as the lord of the dead.

Even this cursory sketch suggests how many parallels we can find between Christianity and pagan religions. Moreover, it was obvious that the pagan faiths were much older than the Christian one. Christianity looked like a mere copycat of these religions, and that’s exactly what many of its pagan critics contended. The Christian fathers countered with a remarkably clumsy response: that Satan, foreseeing that Christ would come to earth, came down first and created religions that were merely diabolical imitations of the truth.

Those of us who find this argument implausible are left wondering exactly what the relationship between Christianity and these pagan cults was. Frazer saw the mystery religions of Attis and Adonis and Osiris as essentially fertility cults: Their rites were designed to mimic and foster the rebirth of life each spring. According to Frazer, Christ had come as a teacher of “ethical reforms”; the mythologies of the fertility cults were gradually assimilated to the faith of Christ’s followers “so as to accord in some measure with the prejudices, the passions, the superstitions of the vulgar.” Frazer writes:

To live and to cause to live, to eat food and to beget children, these were the primary wants of men in the past, and they will be the primary wants of men in the future so long as the world lasts…. These two things, therefore, food and children, were what men chiefly sought to procure by the performance of magical rites for the regulation of the seasons.

This all may sound plausible – as it certainly did to Frazer’s rationalistic late-Victorian contemporaries – but there’s one small problem with it. The idea that the mysteries of Attis and Adonis and Osiris, and by extension of Christ, were mere attempts to reproduce and sustain the cycles of life was known to the ancients and explicitly refuted by them. Plutarch, writing in the late first century CE, contends:

And we shall also get our hands on the dull crowd who take pleasure in associating the [mystic recitals] about these Gods either with changes of the atmosphere according to the seasons, or with the generation of the corn and sowing and ploughings, and in saying that Osiris is buried when the corn is hidden by the earth, and comes to life and shows himself again when it begins to sprout.

Cicero, the Roman statesman and philosopher (106–43 BCE), also says there is something more to the mysteries:

These Mysteries have brought us from rustic savagery to a cultivated and refined civilisation. The rites of the Mysteries are called “initiations” and in truth we have learned from them the first principles of life. We have gained the understanding not only to live happily but to die with better hope.

We can safely say this much: The ancient mysteries were more than rites intended merely to ensure that the crops grew and the animals bred. But what, then, were they? What is the dying “with better hope” that Cicero mentions? And why does the story of Christ, springing from the monotheistic world of Judaism, so much resemble those of the gods that went before?

At this point it would be helpful to address an extremely important issue: the reliability of the historical accounts of Jesus. Apart from a few extremely brief references in non-Christian writers such as Tacitus and Pliny the Younger (which talk about the Christians as a sect but say practically nothing about Christ himself), we have to rely on the canonical gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Scholars unanimously accept these as the oldest gospels, with the possible exception of the Gospel of Thomas, an early sayings collection with a strongly Gnostic tinge; the many other gospels that were written are almost certainly later – one reason they didn’t find their way into the New Testament.

Unfortunately, even these texts present Jesus at a remove. None of them, it is now generally acknowledged, was written by any of the Twelve Apostles or even by anyone who knew or saw Jesus personally. The earliest Gospel, Mark, is dated to around 70 CE; the latest, John, to around 100 (these dates are highly approximate). Nowhere in these Gospels is the claim that the writer himself has seen what he is describing. Indeed most scholars today agree that none of the texts in the entire New Testament was written by any of the Twelve Apostles.

The only surviving eyewitness account of Christ is found in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. Paul did not know Jesus when he was alive, but he writes that after Jesus had appeared to Cephas (Peter), the twelve, and various other witnesses, “last of all he was seen of me also, as of one born out of due time” (1 Cor. 15:5). (Biblical quotations are from the Authorised King James Version.) This experience, usually equated with Paul’s vision on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1–7), is an eyewitness account: Paul is claiming that he has had a vision of the risen Christ like that of the other apostles. Inasmuch as Paul died during Nero’s persecution in Rome in 64 CE, this text is almost certainly earlier than any of the Gospels. But Paul does not say anything more about his experience, and he says almost nothing at all about Jesus before his death.

In their 1999 book The Jesus Mysteries, Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy argue that the extreme scarcity of direct evidence about Jesus, together with the strong resemblance of his story to other pagan myths, means that Jesus did not exist as a historical figure. He was created by Gnostic sages as a kind of Jewish equivalent of the dead and reborn gods of the pagan Mediterranean world.

Freke’s and Gandy’s view, although interesting, seems to be an overstatement given the evidence. They say that Paul’s vision (as described by himself) may have been a later addition to 1 Corinthians, a claim that, to my knowledge, no reputable scholar would agree with; or perhaps that it was a mystical vision of some sort. But the context of 1 Corinthians 15 indicates that, as Christians have always claimed, Paul, like the others who claimed they had witnessed the resurrection of Christ, regarded it as an actual encounter with the risen Jesus. Whatever it was they saw or did not see, this much seems indisputable. Indeed, if we go to 1 Thessalonians, another letter of Paul’s, which was the first New Testament book to be written (it’s generally dated to around 50 CE), we see Paul saying, “The Jews… both killed the Lord Jesus, and their own prophets” (1 Thess. 2:14–15). “We believe that Jesus died and rose again,” he writes in the same letter (1 Thess. 4:14). In both these instances, he is stressing the historical actuality of these events: they are not a myth. Furthermore, Paul is not introducing this idea as a novelty but as a premise that he expects his readers to share.

About the historical Jesus, then, we can say this much: that as early as 50 CE, no more than twenty years after his death and still well in the lifetime of his disciples, his followers preached that he had suffered and died and was resurrected. These facts are not later mythic accretions but among the first things the historical record says about Jesus.

What, then, does this all mean? Paul’s own ideas seem to have grown and changed over time. In 1 Thessalonians, his first surviving epistle, he sounds like a modern-day fundamentalist, obsessed with the Rapture. In fact the idea of the Rapture comes from 1 Thess. 4:17: “Then we which are alive and remain shall be caught up together with [the dead] in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air.” Later, Paul becomes more mystical. In 1 Corinthians he explicitly denies the physical resurrection of the dead: “It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body…. Flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God; neither doth corruption inherit incorruption” (1 Cor. 15:44, 50). This, incidentally, puts mainstream Christianity in the bizarre position of teaching a doctrine – the resurrection of the physical body – that is explicitly denied by its own scriptures. I do not know of any other such case in all of world religion.

Nonetheless, resurrection is at the core of Christianity from its earliest days, just as it was of the mystery religions of Attis and Adonis and Osiris that preceded it. And, like the pagan mysteries, which enabled its initiates to die “with better hope,” Christianity viewed the resurrection not an isolated case that happened to one (possibly divine) man, but something that is the common human inheritance, potentially available to everyone: “Now is Christ risen from the dead, and become the firstfruits of them that slept” (1 Cor. 15:20). This was not the concept of resurrection as commonly taught, but part of what the Church Father Origen (185–253) called “the deeper and more mystical doctrines which are rightly concealed from the multitude.”

The nature of this resurrection lies at the heart of the old pagan mysteries and the Christian faith alike. To best understand it in a short space, it would be helpful to use the common metaphor of a seed, used both by Jesus in the Gospels and by Paul (as well as in some of the pagan mysteries). A seed is something extremely small and contains only in germ the full plant; this is the metaphor Paul uses to compare what he calls “the resurrection body” with the “natural body.” Christ in the Gospels likens the kingdom of heaven to a seed on several occasions as well: for example, “the kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed” (Matt. 13:31).

What, then, is this “seed”? What is the kingdom of heaven, for that matter? If you were to read the works of many theologians, you might conclude that they don’t know. But this is a central concept in esoteric Christianity. It is not difficult to grasp, but it is subtle. I’ve discussed it in detail in my book Inner Christianity, but in essence it comes to this: There is that in you which says “I.” It is consciousness in its pure form; it is never seen, but always that which sees. You may think you are your body or your emotions or your thoughts, but the fact that you can step back and look at all these things at a distance proves that these things are not you – not in the truest and fullest sense. In fact it is your very confusion of your “I” with your thoughts, emotions, and sensations that constitutes the fundamental problem of human existence. Liberation or enlightenment or, as the early Christians called it, gnosis is the freeing of the “I” from its identification with its own experience. Paul writes, “That which thou sowest is not quickened until it die” (1 Cor. 15:36). Esoterically, this means that the “I” must “die” – must detach itself from its former identifications – before it can be “resurrected” or “born again,” that is, realise its fullest potential in a life that is not limited by the body or the psyche. In the course of this liberation the “I” realises its own immortality.

This, in the simplest and most concise language that I can muster, is the secret that I believe lies at the heart of esoteric Christianity and of the Christian mystery itself. To speak of the resurrection of the physical body, explicitly denied by Paul, is to misunderstand; it is the symbolic death and rebirth of the true “I” – called “I am” in the Gospel of John – that is really the point. But it is an arcane point, and not everyone can grasp it. Early Christianity eventually allowed ordinary believers to believe in a physical resurrection because it was easier to understand; only those who wanted to go deeper were told the truth. As Origen writes, “The resurrection of the body,… while preached in the churches, is understood more clearly by the intelligent.” Origen is saying that the doctrine “preached in the churches” is not the whole story. Regrettably, however, as Christianity developed in later centuries, those who had only an inaccurate, secondary understanding of this truth came to lead the church. Because they did not understand the deeper message, they suppressed it, with consequences that have been disastrous for the spiritual life of the West.

In any event, the revelation of the true nature of the “I” makes the correspondence between the Christian mystery and those of the pagans much easier to understand. If these things are true, they are universally true, and if they are universally true, they must have been known in many times and places and cannot be the bailiwick of a single religion. That, I would suggest, is why Augustine can say that the “true religion” always existed. It’s also why the mystery religions so resembled Christianity. They were expressing a universal truth to which Christianity was also pointing.

All the same, this does not entirely explain the innumerable parallels between the Christ of the Gospels and the figures of ancient myth. Often it does seem that characteristics of the ancient pagan gods were later associated with Christ – and at a fairly early stage. The virgin birth, for example, is not mentioned in Mark, the earliest canonical Gospel, or for that matter by Paul. But it does appear in Matthew and Luke, which are generally dated to between 80 and 100. This suggests that by this point certain myths and legends had attached themselves to the basic story of Christ’s death and resurrection.

Exactly how this happened is unclear. There is no contemporary documentation of this process, or, for that matter, of Christ himself apart from the Gospels to serve as a check. The best guess seems to be something like this: The earliest Christians believed they had some experience of the risen Christ, and this was the central part of their message from the very beginning. By the end of the first century, as the Gospels were being written, the historical kernel of the story of Christ was expanded and recast, partly to imitate familiar aspects of pagan myths but also to symbolically express certain truths. That’s why Origen could write:

Very many mistakes have been made because the right method of examining the holy texts has not been discovered by the greater number of readers… because it is their habit to follow the bare letter….

Scripture interweaves the imaginary with the historical, sometimes introducing what is utterly impossible, sometimes what is possible but never occurred…. [The Word] has done the same with the Gospels and the writings of the Apostles; for not even they are purely historical, incidents which never occurred being interwoven in the “corporeal” sense…. These passages, by means of seeming history, though the incidents never occurred, figuratively reveal certain mysteries.

This process began with the Gospels but did not end with them. It continued for several centuries later, as we’ve seen with the Christian appropriation of Christmas and Easter in the fourth century. Later still, in the fifth century, when the cult of the pagan goddesses was suppressed, there was a need for a feminine face of divinity, and the mother of Christ was elevated to this role; many of the attributes of Ishtar and particularly Isis were then attached to her. Christianity’s success was at least partly due to its remarkable genius and flexibility in adapting pagan myths to its own ends. Ultimately, however, the true greatness of the faith lies in its profound and haunting expression of what may be the central mystery of human existence.

Bibliography

Raymond E. Brown, Introduction to the New Testament, New York: Doubleday, 1997.

J.G. Frazer, The Golden Bough, New York: Macmillan, 1922.

Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “Original Jesus” a Pagan God?, New York: Three Rivers, 1999.

The Greek New Testament, edited by Kurt Aland et al. Third edition. N.p.: United Bible Societies, 1966.

G.R.S. Mead, Thrice-Greatest Hermes: Studies in Hellenistic Theosophy and Gnosis, York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, 1972. Originally published 1906.

Origen, Contra Celsum, translated by Henry Chadwick, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Origen, On First Principles, Edited and translated by G.W. Butterworth, New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.