From New Dawn 96 (May-June 2006)

The secret account of the revelation that Jesus spoke in conversation with Judas Iscariot during a week three days before he celebrated Passover. …Jesus said to him, “Step away from the others and I shall tell you the mysteries of the kingdom. It is possible for you to reach it, but you will grieve a great deal.”

– The Gospel of Judas1

From an historical point of view this find is as important as the Nag Hammadi writings discovered half a century ago. Everything tells us that we are dealing with the Gospel of Judas referred to by Irenaeus in the second century AD. It is fantastic that something like that re-appears after 1800 years.

– Dr. Stephen Emmel2

The story of how the Gospel of Judas arrived in the Western world is a fascinating tale. Like many of the so-called Gnostic Gospels, it somehow travelled out of Egypt and arrived in the US with a large price tag. Unlike many manuscripts which vanish sight unseen, luck or providence if you like brought this manuscript not only to light but finally to restoration and publication. In the words of Professor Elaine Pagels, “the discovery of the Gospel of Judas is astonishing.”

Originally unearthed by a farmer in 1978 near El Minya, Egypt, from where it had been hidden in a “tomb-like box” for some 1,600 years, the leather-bound papyrus codex was in superb condition. The farmer secretly sold the codex to an antiquities dealer in Cairo, without advising Egyptian Antiquities. In a clandestine meeting in 1983, the antiquities dealer offered the codex for sale to various scholars in Geneva, however with an asking price of over $3,000,000 and a dubious provenance, the price was considered extraordinary.

Ironically, while the Gospel survived well in Egypt, it seriously deteriorated when stored for some 16 years in a safety deposit box in Hicksville, New York. Finally purchased by antiquities dealer Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos in 2000, the following year the codex was acquired by the Maecenas Foundation for Ancient Art in Switzerland. With the help of National Geographic and an agreement reached with the Egyptian government, restoration work soon began.

Known as the Codex Tchacos (named after Dimaratos Tchacos, father of Frieda Nussberger-Tchacos), it is a 26-page document written on 13 sheets of papyrus leaf in ancient Egyptian, or Coptic. The codex contains not only the Gospel of Judas, but the First Apocalypse of James, the Letter of Peter to Philip, and a small fragment of text that scholars have called the Book of Allogene.

If we focus on the Gospel of Judas, the document is a 3rd century Coptic translation of a now lost Greek text, thought to have been written by a group of early Gnostic Christians before 180 CE. While its significance is much debated, there is no question about its authenticity. There is universal agreement it is the genuine article. “All you had to do was look at this thing once,” said Bart Ehrman, a scholar of early Christianity. “I’ve seen a lot of ancient manuscripts, and there was no question.”3 According to James M. Robinson, America’s leading expert on ancient religious texts from Egypt, “I don’t know of any scholar who thinks this is fake.”4

Heresy Hunting

Back in the 2nd century of the Christian era, the Christian Bishop Irenaeus mentioned a Gospel of Judas was in use among the Kainites, an early Gnostic Christian sect. In part I of his Against Heresy, paragraph 31.1, he wrote:

(Some) stated that Cain owes his existence to the highest power, while Esau, Korak, the Sodomites and all other men are dependants of each other. (…) They believe that Judas the Betrayer was fully informed of these things and that only he understanding the truth like no one else fulfilled the secret of betrayal that confused all things, both in heaven and on earth. They invented their own history called the Gospel of Judas.

The Gospel had been known to exist for some time when discussed by Irenaeus around 180 CE, with his primary source being Justin Martyr. This moves the date back to around 140 CE, and most scholars therefore date the Gospel itself to around 120 CE or even earlier. This is significant because it places the Gospel of Judas within the same timeframe as the Biblical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

The publication of the Gospel of Judas undertaken by National Geographic is unlikely to disturb the mainstream Christian church. In a recent interview, Monsignor Walter Brandmuller, president of the Vatican’s Committee for Historical Science, called it “a product of religious fantasy,” and went on to say, “There is no campaign, no movement for the rehabilitation of (Judas) the traitor of Jesus.”5

From past experience with the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in 1947 and the Nag Hammadi Library unearthed two years earlier, whatever the merits of a document it does not bring about a religious revolution. There is an entrenched power structure within Christendom and regardless of the strength of evidence presented, the Church will use spin, distortion and, if necessary, violence (remember the first crusades were against the Cathars) to preserve its dominion.

The significance of the Gospel of Judas needs to be seen in the context of the larger picture provided by Gnosticism and current scholarship regarding Christian origins. Too often modern Christians live in a sort of self imposed ghetto. They read Christian books, subscribe to Christian magazines, and generally are not exposed to scholarship except through the lens of their chosen leaders or churches. In many cases even when a Christian leader tries to inject scholarship and critical thinking, it is still filtered through a very antiquated religious lens. There does seem to be a surprisingly large gap between modern research into Christian origins, even that generally available, and the information the average Christian receives within his or her community.

Over the last 100 years the academic model that has arisen in regards to Christian origins is radically different from the traditional Christian worldview. It would be fair to say Christianity is sometimes even seen as a Gnostic heresy and not vice versa. While this is an inflammatory way of describing Christian origins, it does seem quite clear that within the early Christian “spectrum” there was an exceptionally wide range of traditions and practices. This diversity was not only tolerated but encouraged and embraced. Christianity was not a single, monolithic tradition handed down from one leader to another in succession; it was diverse and multi-faceted with many dispersed centres of power.

Elaine Pagels, a professor of religion at Princeton who specialises in studies of the Gnostics, recently said in a statement, “These discoveries are exploding the myth of a monolithic religion, and demonstrating how diverse – and fascinating – the early Christian movement really was.”6

Gnostic Christianity

Although later denounced by certain leaders as ‘heretics’, many of these Christians saw themselves as not so much believers as seekers, people who ‘seek for God.’7

– Elaine Pagels

Early Christianity seems to have included many differing viewpoints from the rather staid Judaic Christian mix of James the Brother of Jesus to the esoteric Gnosticism of the followers of Mary Magdalene and Simon Magus. Variations in approach were such that within one movement there were libertine sects that used sex and mind altering substances, and others which were strictly ascetic and celibate. There were groups which were strictly Judaic in focus even to the point of keeping the old laws and festivals of Israel, while others were clearly influenced by the Greek Mysteries and even Buddhist traditions.

Each of these communities had their own sacred texts and interpretations of the teachings of Jesus; the majority would now be considered Gnostic, i.e. they emphasised personal and direct experience of the divine. Accordingly, each of these groups acted like a “Mystery Cult” and had their own specialised practices, mythologies and rites. Many had distinct Gospels which included unique revelations from Jesus to their founders. For example, in the Pistis Sophia, we read of the secret teachings of Jesus to Mary Magdalene and the Gospel of Thomas begins… “These are the secret words which the living Jesus spoke, and Didymus Judas Thomas wrote them down.”8

These secret writings and communities flourished for hundreds of years. It was only in the early 4th century that Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria wrote a letter to some Christians in Egypt ordering them to reject what he called “secret, illegitimate books.”9 In 363 CE the first synod (of Laodicea) was held to decide the official contents of the Bible.

Certainly by the middle of the 4th century, Christianity had become a political force and dissenting views were not tolerated. Under threat and violent persecution, Gnostic communities withdrew from public view, to survive as an ‘underground’ movement. This continued right through to such groups as the Templars and Rosicrucians, and even to the present day.

Clearly, early Christianity offered a wide spectrum of beliefs and practices catering to the unique needs of people with differing levels of spiritual development. This helps us understand the Gospel of Judas. While Christendom has attempted to downplay the significance of this Gospel, its message, like that of Gnosticism in general, is actually quite confronting and challenging.

Secret Teachings

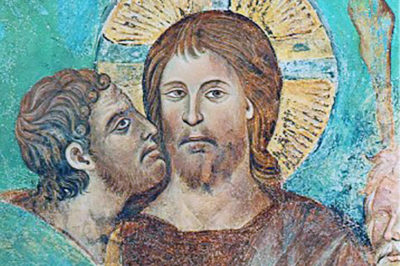

The Gospel of Judas is a secret account of the revelation that Jesus spoke to Judas Iscariot. It portrays Judas as one of the initiates, a specially loved and favoured disciple who undertook one of the most painful missions asked by his teacher, to betray the saviour as part of a greater plan of spiritual import.

The Gospel outlines a specifically Gnostic worldview, offering a cosmology which is fairly consistent with the radical Gnostic sects of the period. Cosmology in Gnosticism is a complex idea with many Aeons, worlds, dimensions and forms. It is impossible to appreciate the cosmology of the Gospel of Judas without these, however, I cannot give them comprehensive coverage here, but I will try to give a general outline.

There is a world of light which is beyond all created forms. This spiritual realm contains various dynamic intelligences or energies, of which one, Barbelo, is discussed in the Gospel of Judas.

For there exists a great and boundless realm, whose extent no generation of angels has seen.

– Gospel of Judas

There are many dimensions or worlds which exist between this higher reality and the physical world, and all are populated with forms of varying potencies.

The physical world is depicted as flawed, even evil, and is beyond the boundary of these worlds. It is the product of a bloodthirsty and ignorant creator deity. His name is given as Nebro, which means ‘rebel’; while others Gnostics call him Yaldabaoth. There are many myths and stories about how he came to exist and create the physical world.

Judas said to Jesus, “[What] is the long duration of time that the human being will live?”

Jesus said, “Why are you wondering about this, that Adam, with his generation, has lived his span of life in the place where he has received his kingdom, with longevity with his ruler?”

Judas said to Jesus, “Does the human spirit die?”

Jesus said, “This is why God ordered Michael to give the spirits of people to them as a loan, so that they might offer service, but the Great One ordered Gabriel to grant spirits to the great generation with no ruler over it – that is, the spirit and the soul…

– Gospel of Judas

While the Gospel of Judas does not present a full account of the creation process, when interpreted in conjunction with other Gnostic texts it certainly presents a mythos which is very much at odds with the standard Judeo-Christian legend. Saklas, a demi-god under Yaldabaoth, creates the body of man while the angels Michael and Gabriel, emissaries of the world of light, allow spirits from the world of light to incarnate within these shells.

This is very similar to Mandaean myths of creation where the physical bodies created by lesser spirits cannot even move off the ground, writhing and screaming in the dirt. In sympathy, emissaries of the light world allow spirits to enter them. But becoming trapped, fascinated by the allure of the flesh, these spirits now believe they are physical rather than spiritual beings.

There is a suggestion, also found in other Gnostic literature, of various degrees of spiritual awakening. Some beings only have one soul, some have two, some have none. In the Gospel of Judas, those with one soul receive it from Michael, while those with both a soul and spirit have received them from Gabriel. Each of these classes are under varying degrees of control by the rulers (principalities and dominions) that manipulate our world.

This model is found within the Gnostic schools where there are three levels of initiation:

1. Hylic – most of sleeping humanity, under full control of rulers.

2. Psychic – partially awakened, under partial control of the rulers.

3. Pneumatics – awakened.

There is an essential dualism within the Gospel of Judas which helps explain the significance of Jesus’s death and the role of Judas. Since man’s origin is within the spiritual dimensions and the flesh is a cage, then death is not to be feared but a form of liberation. Accordingly, Judas helps Jesus escape his prison of flesh and liberate the essential true nature within him.

You will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me.

– Gospel of Judas

The Gnostics taught that in some way or another we must each overcome the body and its demands and liberate the true Christ nature within. While individual praxis may vary from asceticism to libertinism, the goal is the same. In addition, these Gnostics also identify the creator of the physical world as our enemy, and hence see Yaldabaoth as the primary force holding us back from achieving true liberation.

Indeed, in the Sethian tradition, Yaldabaoth is identified with Jehovah and the serpent of Genesis is actually seen as the liberator. This relates back to Irenaeus’ claim the followers of the Gospel of Judas were “Kainites” since in this interpretation, Cain is the saviour, not Abel, and the Sodomites are the people of God, not the slaughtering puritans and so on.

We also find within the Gospel of Judas reference to both Seth and Adamas which is significant as they tie elements of the Gospel to the Naassene or Serpent Gnostic traditions. This has strong resonance with the Greek Orphic Tradition which is superbly covered in The Gnostic Secrets of the Naassenes by Mark Gaffney.

There is a distinct absence of the saving power of the blood of Christ or the vicarious nature of the crucifixion in the Gnostic texts. Indeed the crucifixion and Resurrection are not even mentioned in the Gospel of Judas. The role of Judas shows the path to liberation is in awakening the Christ within and overcoming the restrictions created by both the physical body and the forces of the lower spiritual/physical worlds. These are sometimes represented as the planets, powers and dominions or rulers.

The multitude of those immortals is called the cosmos – that is, perdition – by the Father and the seventy-two luminaries who are with the Self-Generated and his seventy-two aeons. In him the first human appeared with his incorruptible powers. And the aeon that appeared with his generation, the aeon in whom are the cloud of knowledge and the angel, is called [51] El. […] aeon […] after that […] said, ‘Let twelve angels come into being [to] rule over chaos and the [underworld].’ And look, from the cloud there appeared an [angel] whose face flashed with fire and whose appearance was defiled with blood. His name was Nebro, which means ‘rebel’; others call him Yaldabaoth. Another angel, Saklas, also came from the cloud. So Nebro created six angels – as well as Saklas – to be assistants, and these produced twelve angels in the heavens, with each one receiving a portion in the heavens.

– Gospel of Judas

Judas works with Jesus to help liberate him from the power of the body; he plays an important role within the initiatory process of the crucifixion and Resurrection, which some suggest was actually an initiatory drama rather than a real historical event, but that is outside our discussion here.

This Gospel needs to be interpreted within the larger framework of the dualist Gnostic tradition. The motif of Judas as special disciple and the negative interpretation of both the body and the world resonate through the vast majority of the Gnostic sects. In addition, the emphasis on Jesus as a giver of light, a transmitter of the message from the higher dimensions rather than as a sacrifice, is central to a Gnostic view of salvation.

Jesus was seen as a way-shower, an emissary, a being whom we should emulate, not worship. This approach is central to the Gnostic vision; liberation comes through individual effort inspired perhaps by the life of Jesus, but ultimately through our own perseverance. In this way we move towards achieving our own state of divinity, our own theosis.

The Gospel of Judas is certainly a fascinating revelation, though it does not necessarily add greatly to what we already know about the Gnostic vision. What it does do, however, is bring home the significance of this message for today’s world. If the Gospel of Judas had been taken seriously by the early Church and the Gnostics not suppressed, anti-Semitism and all its related violence may not have had such a disastrous effect within Western history. If Judas was only doing his job as a “special” disciple of Jesus, then the whole myth of “Judas the Christ Killer” dissolves and is replaced by Judas, the holder of the Mysteries.

In 2006 with continued violence instigated by self-proclaimed religious fundamentalists, it is perhaps time we rehabilitate the Gnostic tradition. Gnosticism brings a spirit of openness, diversity, individual responsibility and freedom. With the publicity brought about by The Da Vinci Code and now the publication of the Gospel of Judas, it is time we let go of old prejudices, superstitions and narrowly held opinions and allow a different light to shine from beyond the confines of matter.

Recommended Reading

Adam, Eve and the Serpent by Elaine Pagels

Gnosis: The Nature and History of Gnosticism by Kurt Rudolph

The Gnostic Bible: Gnostic Texts of Mystical Wisdom form the Ancient and Medieval Worlds by Willis Barnstone

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

Gnostic Philosophy: From Ancient Persia to Modern Times by Tobias Churton

The Gnostic Religion by Hans Jonas

The Gospel of Judas by Bart D. Ehrman, Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst

Jesus and the Lost Goddess: The Secret Teachings of the Original Christians by Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy

The Jesus Mysteries: Was the “Original Jesus” a Pagan God? by Timothy Freke & Peter Gandy

The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy by Yuri Stoyanov

The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and His Lost Gospel by James M. Robinson

Footnotes

1. The Gospel of Judas, as translated by a team led by Rodolphe Kasser and provided by the National Geographic Society.

2. www.michelvanrijn.nl

3. “Scholars have ‘no question’ on authenticity”, by Tom Avril, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 April, www.philly.com

4. “Another Take on Gospel Truth About Judas, Manuscript Could Add to Understanding of Gnostic Sect”, by Stacy Meichtry, 25 February, Washington Post, www.washingtonpost.com

5. Ibid.

6. “In Ancient Document, Judas, Minus the Betrayal”, by John Noble Wilford & Laurie Goodstein, 7 April, New York Times, www.nytimes.com

7. “The ongoing evolution of Christianity”, by Jane Lampman, May 15, 2003, Christian Science Monitor, www.csmonitor.com

8. “The Gospel Truth”, by Elaine Pagels, April 8, New York Times, www.nytimes.com

9. Ibid.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.