From New Dawn 113 (Mar-Apr 2009)

Historians and archaeologists consistently ignore solid evidence that Captain James Cook was not the first European to discover Australia while government agencies regularly prohibit access to shipwreck sites which would uncover proof for this assertion.

Why is the true history of Australia being covered up? Why does history treat Captain Cook so kindly, despite the fact that in his later years he was an extraordinarily irritable man who, over the most trivial matters, did not hesitate to flog crew members or burn down entire native villages?

And even though all of the expeditions he led ended in partial or complete failure, Cook is generally, almost universally, lauded as the greatest of navigators and his expeditions seen as milestones in navigation history – and on top of all that it is claimed Cook discovered Australia.

Lately the claim has been modified a bit as most people now know that the Dutch were sailing along the coastline of west Australia a couple of hundred years before James Cook was born, and of course Abel Tasman sailed along the south of Australia (then called New Holland) and landed on Tasmania. We also know that the Indonesians traded with the Northern Australian Aborigines for at least 400 years before Cook. And most people now know that the Portuguese were trading out of Timor since the 15th century.

So now we say Captain Cook discovered the east coast of Australia, or did he? And why does it matter if he did or did not?

It matters because history shapes our world view, our culture and our social structures. If we believe a description of the past to be true when in fact it is false, our view of how we arrived at the present is flawed, which in turn allows powerful social structures and groups to exist which might not otherwise be able to justify their existence. This is why Japan avoids including true histories of World War II in its schools’ curriculum.

The idea that an Englishman discovered Australia is fundamental to the maintenance of the notion of Australia as a pre-dominantly white Anglo-Saxon society. There are several subtle messages laying behind the notion of Captain Cook, the great English navigator, sailing around the world and discovering the vast continent of Australia. One of these was important in the 19th and early 20th centuries, affirming the inherent superiority of English society and technology as a justification of the British Empire’s dominion over much of the planet. Another was fundamental to the English claims of ownership of Australia, all of Australia, even though Cook only discovered the east coast.

The British discovery of Australia also underpins Australia’s belief that the British system of government is the best, better than, say, the French or Spanish systems. Likewise, Australia’s legal system, both civil and criminal, is British as is the way we structure our police and miliary forces etc., not because they are the best ways of doing things but because they are the British way. Thus it has been important that the myth of the great Captain Cook was propagated and perpetuated over the last 200 years. Yet there were other nations who also had valid claims on Australia: the Dutch, the French and, importantly, the Spanish, England’s old nautical enemy.

The story of Captain Cook was propagated where ever the English could plant the seed, certainly throughout the British Empire and by default most of North America, but is it the truth? Was Captain Cook the first European to discover Australia, even just the east coast?

The answer in a nutshell is no. It’s as simple as that. Ask any Spaniard and he or she will tell you that Captain Cook used stolen Spanish maps to navigate his way around the Pacific. He also used copies of Abel Tasman’s maps, which he acknowledged because at the time Tasman’s maps were readily available. He does not acknowledge the Spanish maps, however when Cook arrived in Hawaii (which he claims to have been the first European to discover) he was recognised and greeted as a returning god, a god who had visited those islands many years before bringing the Hawaiians knowledge of agriculture. They recognised Cook as this god because he sailed a ship just like the one their previous visitor had sailed, and of which they still made venerated models. A tall, multi-masted ship with huge sails and no paddles: these were models of a Spanish ship.

Cook was quick to see the advantages of being mistaken for a god and pretended to be that god in order to restock his ships with food and water. Sadly for Cook he overplayed his hand and over-taxed the generosity and tolerance of the Hawaiians who realised they had been both duped and exploited, and as a result killed Cook, then cooked and ate him. (Yes Cook got cooked.)

The Spanish, who left the Hawaiians on better terms than Cook, had been regularly sailing the Pacific for about 300 years before Cook entered that vast ocean. Their presence there was the result of the combined efforts of Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan and Spain’s interest in maritime exploration, in the search of new lands. The Spanish ships sailed mostly from Mexico or Peru to Manila following a course utilising favourable winds and currents that flowed from east to west between 5 and 10 degrees south of the Equator until they reached Guam where they restocked with water and other supplies before the final leg of their journey to the Philippines. This was a treasure trade route vital to the Spanish and Mexican economies. Silver, gold and jewels were taken from the slave mines of South America to Manila in huge galleons where they were traded for silks, porcelains and other goods out of China and Asia. This was called the Manila galleon trade and each ship, and there were a number every year, carried enough wealth to equal a king’s ransom.

The Spanish considered the Pacific and everything in it, including Australia, their property and felt completely secure in their Pacific domain until Sir Francis Drake sailed around Cape Horn and began pillaging the Spanish treasure fleets there.

The Spanish Empire had been built around maritime exploration and expansion. It is inconceivable that Spanish ships sailed the Pacific Ocean for 300 years and not discovered a continent the size of Australia. But where is the proof?

The Dieppe Maps

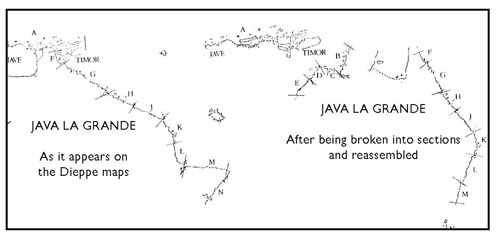

The first and most obvious piece of proof which is continually ignored by mainstream Australian historians is a well known collection called the Dieppe maps, a set of maps made in the town of Dieppe in France in the 16th century. These provide clear proof of either Spanish or Portuguese exploration of Australia’s east coast at least two hundred years before Captain Cook. The maps clearly show the east coast of Australia as well as almost all the rest of Australia’s coastline. In the Dieppe maps the name given to the Australian continent is “Java la Grande.”

The Dieppe maps have proved to be actual copies of Portuguese maps; another similar set of maps are the Dauphin maps after a series of copies of the Dieppe maps made for the French Dauphin. Also there is the Vallard map which is essentially the same map as the Dieppe and Dauphin maps.

The Dauphin maps are elaborately decorated, not for any scientific or geographical reason but simply to make the maps more interesting to his Royal Highness the Prince Dauphin – an important thing to remember as many historians attempting to discredit these maps cite the images used in the decorations to dismiss the cartographic accuracy of the Dauphin maps.

When considering the Dieppe maps one should remember just how important navigation maps were in the European world of 400 years ago. It was the “Age of Exploration,” a historic time of maritime expansion, of empire building, of ruthless exploitation and greed. It was an age of conquest, trade, navies and more greed.

The rulers and populations of the European nations wanted wealth, whatever it took. The pathways to wealth were on the sea and those who possessed the navigation maps showing how to travel those pathways held the keys to unimagined riches.

In those days (up until the 19th century) the information contained in items such as the Dieppe and Dauphin maps was often priceless, top secret, government property, and jealously guarded as the plans to nuclear weapons or interplanetary space travel might be guarded today. For this reason various nations and their captains contrived ways of concealing the information contained within their maps – maps in code so to speak. Cracking the secret code of those ancient Dieppe maps was the work of Australian Army map maker and surveyor Brigadier Lawrence Fitzgerald O.B.E., a man of genius largely ignored by mainstream academia.

Brigadier Lawrence Fitzgerald

Fitzgerald with his extensive practical and theoretical experience with maps and map making could clearly see there were sections of the Dieppe maps that resembled Australia’s coastline but there were also sections that did not. After considerable research the Brigadier discovered that the maps which ancient navigators used on ships were not in the form we generally think of – that is a huge rolled up sheet of parchment or paper that covered the Captain’s entire table. No, they were in sections on separate sheets generally kept loose in a folio or even in separate folios. To protect the information in the maps, should they fall into rival hands, the maps did not join up neatly or even had small components to make reassembling and interpreting the maps difficult or impossible if the keys to the codified maps were not available.

Brigadier Fitzgerald realised that he only had to divide the Dieppe maps into the appropriate sections and then discover how to reassemble them in the correct order. This he did and in his book Java la Grande he clearly shows that the Portuguese had accurately and extensively mapped the Australian coastline more than 200 years before Cook. His work is largely ignored, even ridiculed, by most Australian and British historians. Why?

The next question most people ask is: “If the Spanish and/or the Portuguese visited Australia before Cook, why are there no archaeological traces of them?” The answer is simple: “There are many.” But they are ignored, covered up, or hidden.

Possible Pre-Cook Shipwrecks

Sand miners uncovered the remains of an oak ship under the sand on a beach near Byron Bay. The ship was reburied in the sandmining process but a private citizen paid for a piece of timber retrieved from the ship to be carbon-dated by an independent laboratory. The results came back that the wood (oak) dated to the 16th century. Archaeologists from the University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales got excited and they organised for a magnetometer survey of the area. The ship was relocated under the sand and a dig planned to excavate it and solve the mystery. A week before the dig was scheduled to begin word came high in the New South Wales government that the dig could not proceed, and it was stopped. There were no reasons given. That was in 1995, and the shipwreck is still sitting there under the sand.

Another example is a shipwreck buried under the sand dunes at Facing Island near Gladstone, Queensland. This shipwreck was seen after a storm in the early 19th century but its location was lost when the sand covered it again. A 5 feet (1700 mm) long bronze cannon with the date of 1596 stamped on it and other artefacts were found around Gladstone in the mid 19th century and the subject of articles in the early Australian press, several essays, investigations and books.

In the late 1990’s the wreck on Facing Island was again exposed for a few days by a cyclone. Fortunately a fisherman saw it and took photographs as well as noting the shipwreck’s location, all of which he gave to the local Maritime Museum. The Maritime Museum, with suitably qualified personnel, applied to the government for a permit to investigate the shipwreck. The application was refused and a warning given that anyone attempting to excavate or otherwise investigate the wreck would face prosecution under the draconian penalties of Australia’s “Historic Shipwrecks Act.” The wreck is still buried under the sand on Facing Island.

The list of possible pre-Cook shipwrecks is long and includes the “Mahogany ship” at Warrnambool. In the case of the Mahogany ship, the fact that it is described as being built of mahogany indicates it was built in either South America or the Caribbean as this is the only area that mahogany trees grow. As it was an old wreck in 1836 when it was first seen, it could only have been of Portuguese (Brazil) or Spanish (the rest of South America) origins.

The Stradbroke Island Galleon in Queensland is a ship built of European oak about 30 metres long. It lays in a peat swamp where it was first seen in the 1860s and which the local Aborigines said had been in the swamp a long time. In the case of the Stradbroke galleon, we actually have historic records of Aboriginal oral traditions that report the arrival of the shipwreck victims in an Aboriginal camp and even the fact that one of them was named Juan!

Both of these shipwrecks have an extensive presence on the Internet so I will not go into detail about them here; a simple Google search will bring up a wealth of information.

Another ancient shipwreck was noted by Governor Oxley in 1821 off the beach at Fingal Head in Northern NSW. There is also a shipwreck at Caravel Creek in the Hinchenbrook Channel in Queensland and the list goes on.

Pre-Cook Artefacts

Apart from the pre-Cook shipwrecks there are numerous artefacts that have been found scattered around the sites of these wrecks or actually taken off the wrecks in the early days before the government actively intervened to suppress information about possible pre-Cook shipwrecks.

For example, coins were found on the beach where the Mahogany ship is buried. These have generally been described as Spanish coins but I would guess they could be Portuguese as they have never been identified by experts.

In the case of the Stradbroke Island Galleon there have been coins, a sailor’s dirk, a brass walking stick head dated by experts to Spain or Portugal in the 16th century, a rapier sword blade, a ship’s bell and various other items.

A lead weight has been found by a university geologist while digging for pumice in undisturbed sand strata on Fraser Island, Queensland. This lead weight was accurately dated as having been laid down on Fraser Island over 400 years ago and, using radioactive isotope fingerprinting, the lead can be proved to have come from mines in the south of France.

A bronze 16th century Portuguese cannon is on display at the Queensland Maritime Museum in Brisbane, which was found on the Great Barrier Reef. And the list goes on and on.

Australian History

Why is all this evidence ignored by Australian historians and archaeologists? Why does the government continue to block the excavation of possible pre-Cook sites?

Until the Mabo court case and the granting of Aboriginal Land Rights, the obvious reason would have been the legal implications allowing a challenge to Cook’s pronouncement that Australia was Terra Nullus – unoccupied land. It was this proclamation that allowed Britain to occupy Australia without entering into negotiations with its existing occupants, the Aborigines.

After Mabo this reason no longer applies and an even sillier, pettier motive may exist: the defence of reputations. Many Australian historians and archaeologists have for so long scoffed at the idea any nation reached and explored the east coast of Australia before Cook that they have entrenched themselves in their position. There is no way for them to change their “official” position without admitting they ignored solid scientific evidence in defence of a historic status quo. In universities and museums there are professors and doctors of history and archaeology who have painted themselves into a corner by systematically deriding all those who present theories or evidence that Cook was not the first European to discover and explore Australia. They use their influence and position to block any attempts to get the final proof they are wrong, proof that would require history books to be re-written and leave reputations in tatters.

History shows us that these attempts to falsify history, to block discovery, ultimately fail. It’s only a question of time.

Greg Jefferys is the author of the book The Stradbroke Island Galleon, The Mystery of the Ship in the Swamp, which is available as an e-book.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.