From New Dawn Special Issue Vol 8 No 3 (June 2014)

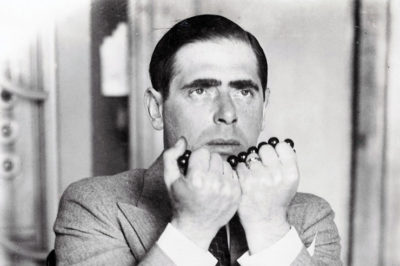

On the morning of 7 April 1933, south of Berlin, workmen came upon a grisly discovery. Near the road that linked the German capital to the town of Baruth was the bullet-riddled body of a man, dressed in evening clothes. Death had come, execution-style, from two shots to the head. Beyond that, it was hard to tell much. The corpse was maggot-ridden, and animals had gnawed the face making it practically unrecognisable. Investigation by Berlin police Kriminalrat Hermann Albrecht quickly determined that the deceased was Erik Jan Hanussen, a well-known Berlin clairvoyant, astrologer and public figure who had gone missing two weeks earlier.

The critical questions, of course, were who killed Hanussen and why. It seemed the dead man had many enemies. Rival psychics, embittered ex-employees, jilted lovers, cuckolded husbands, blackmailed victims, and underworld denizens all had reasons to wish him dead. Albrecht perhaps wisely concluded that the psychic had been “taken for a ride” by Berlin gangsters.1 The case remained unsolved.

As Albrecht certainly knew, Hanussen’s real assassins were members of the Nazi Brownshirts (SA) organisation in Berlin. This was odd, because up to his demise, Hanussen was a conspicuous friend of many Nazis, not to mention a Party member and an honorary member of the SA. He knew Adolf Hitler himself and his accurate, pro-Nazi predictions had earned Hanussen the nicknames “The Prophet of the Third Reich,” “The Nazi Rasputin,” “Hitler’s Nostradamus,” and others. Odder still was the fact that Hanussen was a Jew.

Hanussen’s story is fascinating, improbable and perplexing and has been dissected in various biographies, perhaps most notably Mel Gordon’s Erik Jan Hanussen: Hitler’s Jewish Clairvoyant (2001) and Arthur J. Magida’s The Nazi Séance: The Strange Story of the Jewish Psychic in Hitler’s Circle (2011).2

This article will offer a brief overview of Hanussen’s career, but focus attention on a few questions that merit closer examination. First, are there any clues to Hanussen’s talents and behaviour to be found in his family background? Was Hanussen involved in espionage, or did he have any connection to intelligence services? Finally, what was the nature of his relationship with the future Fuhrer?

Who Was “Erik Jan Hanussen”?

Hanussen wasn’t Hanussen at all. His true name was Hershmann Chaim (later Hermann) Steinschneider. He was born in Vienna in 1889, the son of Siegfried Steinschneider, a ne’er-do-well Jewish vaudevillian and travelling salesman. Herschmann’s birth was registered in Prossnitz (today Prostejov in the Czech Republic), the Moravian town which was the traditional home of the Steinschneiders. The family and the place have interesting histories.

In the 18th century, Prossnitz had a thriving Jewish community which produced an impressive array of rabbis and Talmudic scholars. Among these were Rabbis Daniel Prossnitz the Younger and his son Aaron Daniel Prossnitz, who adopted the surname Steinschneider. Both were vunder-rebbes reputed to have “magical and curative” powers.3 Mel Gordon speculates that Steinschneider, meaning “stone-cutter” or “stone tailor,” derived from Aaron Daniel’s practice of making Kabbalistic paper amulets from carved stone blocks.4

But all was not as it seemed in Prossnitz. The town’s Jewish community was a hotbed of the Sabbatian heresy, a secretive sect which revered the 17th century “Messiah” Sabbatai Zevi.5 Sabbatians not only regarded Zevi as the Messiah, but also followed his antinomian teachings that advocated the deliberate transgression of Jewish Law and a Gnostic-like idea of “redemption through sin.”6 Moreover, Prossnitz was infiltrated by the even more radical and occultic Frankist sect whose practices included orgiastic rituals.7 In the opinion of Gershom Scholem, Sabbatian influence completely subverted Orthodox rabbinic culture in Prossnitz.8 One infamous proselytizer of Sabbatian beliefs was Judah Leib (Loebele) Prossnitz who claimed to be able to invoke the Shekinah (the Divine Presence), a stunt he pulled off with a back-lit set that made magical letters appear on his chest.9

The trick sounds very much like something Hanussen might have tried two centuries later. But, given that he never lived in Prossnitz, how much could he have been influenced by its sectarian culture? Rabbi Marvin Antelman alleges that the Steinschneiders were a “Sabbatian family” and singles out Hanussen’s great uncle Moritz Steinschneider as a prime example.10 Hanussen doubtless learned something about Prossnitz from his father. He did visit, and amazed locals by performing an exorcism on a milk maid.11 Consciously or not, Hanussen’s later behaviour, from his denial of his Jewish roots, to his rejection of sexual and other mores, obsession with mysticism, and even his association with virulent anti-Semites, all more or less conformed to the Sabbatian-Frankist mould.

A fundamental problem in dealing with Hanussen pre-1920s is that most of what is known about him comes from a single source, his 1930 autobiography, Meine Lebenslinie (“My Lifeline”). To call it self-aggrandising is an understatement, though it seems accurate enough as regards time and place. The author dances around the matter of ethnic origins, stating that he was born in Vienna (true), not in Denmark, Sicily or Tarnopol, the latter a largely Jewish town in the far reaches of the old Empire.12 If he is to be believed, his psychic powers first manifested in the womb, when he willed his unwed parents to marry.13

Hermann “Harry” Steinschneider followed in his father’s footsteps and spent his youth travelling around Central Europe with circuses and vaudeville shows where he rubbed-elbows with fortune-tellers, strongmen, hypnotists, magicians and faith-healers. He picked up many of their tricks, invented a few his own, and put together a stage act based on mind-reading and hypnotism. He also ventured into journalism. In the years before WWI, he worked for a notorious Viennese scandal-sheet, Der Blitz, which earned most of its income by taking money to keep stories out of its pages.14 Steinschneider would apply this lesson well in his subsequent career.

During the war, Harry served in the Austro-Hungarian Army where his evident talents as a mind-reader and dowser got him out of the trenches and into cushy duty in the rear. He even organised a séance or two. Whether this was proof of genuine extra-sensory ability or just clever trickery was, as always, a matter of opinion.

Steinschneider played around with several aliases, among them Siegfried Krakauer and Saul Absolom Herschwitter, which still carried a strong hint of Semitic ancestry.15 Around 1919, he finally latched onto Erik Jan Hanussen, claiming to be a Dane of noble background whose telepathic powers led him to become a showman, psychic investigator and student of the occult. There was, of course, nothing Danish about him, and no one seems to have taken the role too seriously, least of all Hanussen. On a 1919 visit to Prague, he openly boasted of his “Czech-Jewish” heritage.16 Hanussen was whatever the circumstances best suited he should be.

In postwar Vienna, he earned notoriety as a stage mentalist and hypnotist. He even tried his hand at movie star in the low-budget Hypnose (“Hypnosis”) in which he portrayed a clairvoyant gumshoe battling the evil schemes of a Svengali swami. He earned more attention, and money, playing psychic detective in real life. His most famous case involved mysterious thefts from the printing bureau of the Austrian State Bank. Newly-printed bills were vanishing and authorities were at a loss to explain how. Hanussen solved the case by the simple deduction that the caper had to be an inside job. He correctly fingered the culprits which led to the recovery of most of the purloined notes.17

His crime-solving exploits, however, earned him the enmity of Vienna’s Polizeidirektion who suspected him, not without reason, of either setting-up crimes he purported to solve or being privy to inside information. But Hanussen found at least one champion among the police. Dr. Leopold Thoma was a psychoanalyst, paranormal researcher, and chief of the Psychologische Abteilung of the Viennese police. In 1921 he formed his own Institut fur Kriminal Telepatische Forschung (“Criminal Telepathic Research”). His and Hanussen’s paths would cross again a few years later.

When Viennese authorities cracked down on the exhibition of hypnotism, Hanussen looked for greener pastures. With Austrian tobacco magnate Hans Hauser, Hanussen became part of a scheme to sell surplus military equipment to the Greeks who at the time were engaged in a bitter war against the nascent Turkish Republic. The affair reeks of international intrigue, though Hanussen’s job, supposedly, was to use his hypnotic power as added leverage in negotiations.18

It may be significant that in the Balkan tobacco trade, Hauser almost certainly dealt with the Tobacco Company Ltd, a British firm which also happened to “provide cover in Europe for S.I.S [MI6] agents and ex-employees of the secret service.”19 Moreover, the British backed the Greeks, while the French, Italians and Soviets quietly supplied weapons to the Turks. Hanussen recalled that he and a companion were refused landing on the Italian controlled island of Rhodes on suspicion that they were Greek spies.20 His subsequent wanderings through the Levant and North Africa added much to his knowledge of Eastern mysticism but also provided ample opportunity for spying. He claimed to have aided Egyptian police in combating a ring of hashish smugglers, though one has to wonder if it wasn’t Hanussen doing the smuggling.21

In 1924, Hanussen crossed the Atlantic for an American tour but found Yankee audiences largely unresponsive to his act. In Europe, however, especially in Germany, Hanussen became a big draw and by 1928 billed himself as the “Wizard of the Ages” and expanded his repertoire to include, palmistry, graphology and astrology.22 His bread and butter, however, remained mind-reading. Typically, audience members handed written questions to an assistant and the Amazing Hanussen divined the query and the answer through his mental powers – plus a secret code between him and the assistant. He continued to consult in criminal cases, among them the “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” a serial murderer who terrorised the city during 1929-30. He also offered private readings to rich clients and allegedly became an “adviser to European royalty.”23

Fame, however, drew opposition. In 1928, a prosecutor in the Czechoslovak town of Leitmeritz charged Hanussen with fraud and larceny, basing his case on the fact that clairvoyance did not exist. In a long, public trial Hanussen won acquittal by successfully demonstrating his “powers” to the judge, or by faking them so well no one could catch him.24

Berlin & Hanussen’s Rise to Power

By 1930, Hanussen pitched his tent more or less permanently in Berlin where he became a celebrity of the first order and a symbol of the decadent hedonism of the dying Weimar Republic. His ability to gain such recognition is all the more remarkable given the competition. The German Capital was home to thousands of seers, hypnotists, faith-healers, and mystics of one variety or another.25 His lavish performances at the La Scala and other theatres were attended by the likes of Marlene Dietrich, Sigmund Freud, Peter Lorre, Fritz Lang – and Hermann Goering. Hanussen acquired fancy cars, a yacht, and an airplane, as well as a small publishing empire of books, magazines and newspapers which tirelessly promoted him, his products and his predictions.

His wealth was enhanced through blackmail (harkening back to his Blitz days) and influence peddling. Dubbed by Mel Gordon the “Magister Ludi of Sex,” Hanussen hosted, and secretly filmed, private séances that attracted a heady mix of politicians, aristocrats, movie stars and industrialists.26 The affairs catered to all sexual persuasions, and some guests wound up in compromising positions which they were willing to pay to keep quiet.27 He also extended private loans to “special friends,” among them prominent Nazis such as Wolf Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, chief of the SA organisation in Berlin, a libertine, degenerate gambler and reputed connoisseur of the “black arts.”28

Whatever his occult abilities, Hanussen was a clever, unscrupulous and venal character who insinuated himself into the confidence of important people in Germany, and elsewhere. He clearly had a talent, one way or another, for obtaining secret information. His currency as an informant only increased when he gained access to Hitler. All this made the phony Dane an asset that any intelligence agency would have been anxious to exploit.

Interestingly, another occultist making his home in Berlin during 1930-32 was the notorious Aleister Crowley. Crowley had a long connection to British intelligence, and part of his purpose in Germany was watching and reporting on certain individuals.29 Given Hanussen’s prominence and his proclaimed expertise in hypnotism and tantric sex, there is no way the Great Beast would have ignored him. Oddly, there is no discernible mention in Crowley’s period diaries of Hanussen or anything relating to him.30

However, they were not without indirect connections. By 1930, the aforementioned Dr. Leopold Thoma had again cropped up in Hanussen’s life and become one of his closest collaborators. Thoma was well-acquainted with fellow Austrian psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, a man Crowley claimed to know personally and to work with in Berlin.31 Moreover, Thoma became pals with Dr. Alexander Cannon, another psychiatrist, paranormal researcher and friend of Crowley who crossed paths with Hanussen.32 Cannon, sometimes dubbed the “Yorkshire Yogi” or the “leader of black magic in England,” would later face accusations of being a Nazi sympathiser and German spy.33 Last, but not least, the phony Dane was a confidant of Hanns Heinz Ewers, a German writer and occultist who was at the time a fervent Nazi with access to Hitler plus an old associate of Crowley.34 Thus, the latter had a number of channels through which he could have gleaned information from or about Hanussen.

The Crowley-Hanussen connection may be at the root of René Guénon’s later assertion that the Beast infiltrated Hitler’s circle and made himself a “secret counsellor” of the Nazi leader.35 There is no indication that Crowley got anywhere near the future Fuhrer, but Hanussen certainly did.

There is also the possibility that Thoma was working for Austrian intelligence. The Vienna Polizeidirektion, with which he remained connected, was involved in intelligence and counterintelligence activity.36 Finding out what was on the mind of native son Adolf Hitler would have been a high priority. Hanussen, again, could have been a very valuable source of information.

In 1933, Pierre Mariel, a writer with ties to French intelligence, authored (as “Teddy Legrand”) a curious book, Les Sept Tetes du Dragon Vert (“The Seven Heads of the Green Dragon”). It claimed to reveal the machinations of an international conspiracy which, among others things, was behind Hitler’s rise to power. Hanussen appears thinly disguised as the “Man with the green gloves,” an agent of the conspiracy.37 Years later, in a book on Nazi occultism, Mariel, writing as “Werner Gerson,” claimed that “Hanussen was a spy for Britain” based on the alleged admission of ex-British agent John Goldsmith.38 If there were no spy agencies exploiting Hanussen, there certainly should have been.

Hanussen & Hitler

Exactly when and how Hanussen met Hitler is a matter of uncertainty and debate. Writer Juri Lina asserts, improbably, that their association began in 1920.39 Gordon argues that the pair met, via Helldorf, in late June or early July 1932. Palacios thinks the intermediary may have been Ewers and that the meeting occurred towards the end of 1932, while Magida wonders if the two ever met at all.40 In 1943, Walter Langer compiled a “Psychological Profile” of Hitler for the American OSS. One of his sources was dissident Nazi Otto Strasser, himself a former admirer of Hanussen, who reported that “during the early 1920’s Hitler took regular lessons in speaking and in mass psychology from a man named Hamissen [sic] who was also a practicing astrologer and fortune teller.”41 In his own writing, Strasser simply puts the meeting in the “post-war period” and describes Hanussen as a “super-clairvoyant” who acted as Hitler’s “medium.”42 In World Diary, contemporary American journalist Quincy Howe identifies 1930 as the year in which Hitler “constantly consulted a Jewish hypnotist who had changed his name from Steinschneider to Hanussen.”43

By 1932, however, what Adolf wanted from the psychic wasn’t elocution lessons but glimpses into the future. As early as 1930, Hanussen had prophesied that Germany would receive a dictator of radical-socialist stripe, though his publications satirised politicians, including Hitler. That changed in early 1932. Hitler was running for president against the incumbent, Paul von Hindenburg. Hanussen predicted that Hindenburg would win (he did) but that Hitler would become chancellor within a year. From this point on, Hanussen and his publications took a decidedly pro-Nazi stance.

However, the incident that may most have attracted Hitler’s notice, as it did other’s, had nothing to do with politics. In May 1932 racers gathered in Berlin for the AVUS Grand Prix. One of them was young Czech nobleman Georg Christian von Lobkowicz. A few days before the race, Hanussen prophesied that Lobkowicz would have a fiery accident. A few minutes into the event, his Mercedes racer crashed, killing him instantly.44 Investigation showed the tragedy was the result of a freak mechanical failure. Even Hanussen’s most stubborn doubters were hard-pressed to explain how he could have faked this. Enemies were not above suggesting that the psychic connived to sabotage Lobkowicz’s car, possibly in league with gamblers. The young Czech also had caught the fancy of a woman Hanussen desired, so jealously was another possible motive. To most, though, the crash was proof positive that the Dane really was a seer. Arthur Magida wonders if through years of mental discipline, Hanussen had actually developed some psychic ability.45

A meeting with Hitler followed soon after and Hanussen assured jittery Adolf he need not worry about the upcoming elections. Sure enough, the Nazis scored a huge success in the July balloting, doubling their seats to become the biggest party in the Reichstag. On New Years Day 1933, Hanussen cast a horoscope and declared Hitler would be Chancellor by months end. That, too, came to pass.

Palace of the Occult & The Reichstag Fire

Hanussen seemed at the peak of his power. He wasn’t just associating with Nazis, he was one. Even his trusted secretary, Ismet Dzino, was a Party and SA man. In addition to being the favoured soothsayer of the new regime, he was about to open his opulent Palace of the Occult. The Capital’s elite clamoured for invitations. But there was trouble brewing. His tilt to the Nazis earned Hanussen the enmity of the Communist press which had published proof of his Jewish ancestry. Hanussen did his best to brush off the matter and his Nazi pals like Helldorf remained steadfast, for the time being anyway.

The Palace of the Occult opened its doors on the evening of 26 February. In a semi-private séance, one of Hanussen’s mediums, a former actress, Maria Paudler, had a fateful vision. In a trance, she claimed to see a “great building” on fire.46 The press attributed the prediction to Hanussen himself. Less than 20 hours later, the Reichstag was ablaze. The Nazis blamed the fire on a Communist plot and rammed through emergency powers that gave Hitler dictatorial control. Berlin police arrested Marinus van der Lubbe, a Dutchman with Communist connections and a history of arson. The general assumption is that the Nazis were behind the blaze and used van der Lubbe as a patsy. Kugel suggests that the hypnotic puppet master controlling the Dutchman was Hanussen.47 Gerson/Mariel suggests another possibility: that the psychic instigated the fire at the behest of someone who wanted to discredit Hitler. If so, the plot backfired badly.48

By mid-March, most of Hanussen’s Nazi friends, including Helldorf, found themselves ousted or re-assigned. On 24 March, a brace of SA dragged the psychic to Gestapo headquarters for questioning. They cut him loose, but the next evening three men snatched him off the street, and he was never seen alive again. The easiest guess is that the Nazis killed Hanussen because they discovered he was a Jew, but it really makes no sense. Evidence of his Hebraic origins had been available for months, and his Party comrades had not rejected him. There was no compelling reason for them to do so now. Another theory, that Helldorf and others murdered him to escape their debts, ignores the fact that they would be killing the golden goose. There is no indication Hanussen made any attempt to collect his debts or that he was unwilling to loan more.

Hanussen’s demise is almost certainly tied to the Reichstag Fire, but there could be more to it. Most of Hanussen’s Nazi contacts were linked to the SA, and most of them to Ernst Roehm, Hitler’s only remaining serious rival. Just over a year later, Hitler and the SS would kill Roehm and dozens more SA leaders in the so-called Night of the Long Knives. Several, including Roehm, were ex-associates of Hanussen. Helldorf escaped, but took part in anti-Hitler intrigues and died for his part in the failed 1944 assassination attempt on the Fuehrer. In contrast the three SA men later identified as Hanussen’s killers all survived to perish in WWII and one of them, Rudolf Steinle, rose to become an officer of the Gestapo and the SS. Hanussen, therefore, may have been an early casualty of intra-Nazi intrigues.

An interesting epilogue to the story involves Hanussen’s secretary, Ismet Dzino. Variously described as a Bosnian, Turk or Lebanese, he married a young Englishwoman, Grace Cameron, against his master’s advice. Hanussen warned him that if they married, she would die and Dzino would become a murderer and suicide.49 The Gestapo arrested Dzino immediately after Hanussen’s death, but Grace, using her contacts at the British Embassy, secured his release. According to a report in a Swiss paper, they later appeared in London where Dzino told friends that the Gestapo was after him because he possessed “important documents about the friendship of his master with certain Nazi leaders.”50 The documents remained in London, but Dzino and wife took up residence in Vienna. Did Dzino or his wife have links to British intelligence? Who took charge of the documents? Did Crowley or Cannon play any part in this?

In Austria, Dzino fell on hard times and eked out a living as croupier. He became possessed by jealously which drove Grace to flee. In September 1937, he talked her into a reunion where he shot her, their four-year-old son and then turned the gun on himself. Hanussen’s prediction came true.

There was the inevitable rumour that the corpse wasn’t Hanussen, that the Trickster avoided his enemies by again changing form and disappearing. It’s another doubtful, but intriguing, possibility.

Footnotes

- “Seer Who Foretold Hitler’s Rise Found Slain,” New York Times (9 April 1933), 12, and “Hellseher-Leiche im Wald – Vor 80 Jahren wurde Erik Jan Hanussen von einem SA-Kommando nahe Zossen erschossen,” Maerkische Allgemeine (Online), 21 March 2013 (accessed 10 April 2014).

- German readers should also consult Wilfried Kugel’s Hanussen: Die wahre Geschichte des Hermann Steinschneider (1998), and for Spanish readers there is also Jesus Palacios, Erik Jan Hanussen, la vida y los tiempos del mago de Hitler (2005).

- Mel Gordon, Erik Jan Hanussen: Hitler’s Jewish Clairvoyant. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2001, 4.

- Ibid.

- “Prossnitz,” The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12394-prossnitz (10 April 2014). The sect name is also commonly rendered Sabbatean.

- Gershom Scholem, “Redemption Through Sin,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism. New York: Schocken, 1971, 78-141.

- Ibid. and Jay Michaelson, “Heretic of the Month: Jacob Frank.” American Jewish Life Magazine (March/April 2007), www.ajlmagazine.com/content/032007/heretic.html (28 March 2014).

- Scholem, 141.

- “Prossnitz, Loebele (Prostiz),” The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906), www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12395-prossnitz-lobele-prostiz (10 April 2014).

- Marvin S. Antelman, To Eliminate the Opiate, Vol. 1. Jerusalem, 1974, 137.

- Gordon, 40-41.

- Hanussen, Meine Lebenslinie (orig. 1930), Kindle edition, Frankfurt a. M.: Wunderkammer Verlag, 2012, location 74.

- Ibid.

- Markus Kompa (with Wilfried Kugel), “Erik Jan Hanussen – Hokus-Pokus-Tausendsassa.” Telepolis Magazin, www.heise.de/tp/artikel/27/27562/1.html (10 April 2014).

- Hanussen, Ibid.

- Gordon, 77.

- Hanussen, loc. 2359-2434.

- Hanussen, loc. 2447-2482.

- Robin Lockhart, Reilly: Ace of Spies. New York: Penguin Books, 1984, 136n.

- Hanussen, loc. 2977.

- Kugel, 60.

- Kompa. Ibid.

- New York Times, Ibid.

- “Clairvoyant Proves Power in Czech Court,” New York Times (29 May 1930), 8.

- Gordon, 181.

- Mel Gordon, Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2008, 216.

- Kompa, Ibid.

- Gordon, Hanussen, 213, and Kompa, Ibid.

- Richard B Spence, Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley, British Intelligence and the Occult. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2008, 210-213.

- My thanks to William Breeze and the OTO Archives for this information.

- Spence, 214-215.

- Gordon, Hanussen, 252. After the Nazis came to power, Cannon (and maybe Crowley) helped Thoma emigrate to Britain.

- “Edward VIII’s Links to a Mystic,” BBC News (6 Dec. 2008). news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/7767919.stm.

- Werner Gerson (Pierre Mariel), “Mage ou Espion?,” in Le Nazisme: societe secrete. Paris: J’ai Lu, 1972, humanisme.canalblog.com/archives/2010/08/22/18871564.html (10 April 2014) and Gordon, Hanussen, 195. Like most of Hanussen’s Nazi associates, Ewers later was an outcast from the Party.

- Guénon to Marcelo Motta, 1949, as quoted in Giorgio Galli, Hitler e il nazismo magico. Milan: Rizzoli, 1989, 129.

- Mario Muigg, “Geheim-und-Nachrichten-Dienste in und aus Oesterriech, 1918-1938.” SIAK-Journal, #3 (2007), 64-72.

- Richard B. Spence, “Behold the Green Dragon: The Myth and Reality of an Asian Secret Society.” New Dawn 112 (Jan-Feb 2009), 69.

- Gerson, Ibid.

- Juri Lina, Architects of Deception. Stockholm: Referent, 2004, 422.

- “Jesus Palacios nos habla sobre el mago de Hitler.” Akasico (1 April 2006), www.akasico.com/noticia/492/Ano/Cero-Entrevistas/Jesus-Palacios-nos-habla-sobre-el-mago-de-Hitler.html (19 April 2014); Arthur J. Magida, The Nazi Séance: The Strange Story of the Jewish Psychic in Hitler’s Circle. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, 169-170.

- Walter C. Langer, A Psychological Profile of Adolf Hitler: His Life and Legend. Washington, DC: Office of Strategic Services [1943], 9. www.nizkor.org/hweb/people/h/hitler-adolf/oss-papers/text/profile-index.html (3 April 2014).

- Otto Strasser, Hitler and I. London: Jonathan Cape, 1940, 37.

- Quincy Howe, World Diary, 1929-1934. New York: McBride, 1934, 54.

- “Motor Race Tragedy,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (24 May 1932), 9.

- Magida, 138.

- Geoffrey Ashe, Encyclopedia of Prophecy. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2001. 99.

- Kugel, 231-234.

- Gerson, Ibid.

- Gordon, Hanussen, 254.

- “Après avoir tue sa femme et sa fils, l’ancien secretarie du mage Hanussen se suicide a Vienne,” L’Impartiale (29 Sept. 1937), 3.

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.